Istanbul-based artist Banu Cennetoğlu, whose work explores the way knowledge is collated and distributed, and its subsequent effect on society, has worked with the List since 2002.

This is the first time the List has appeared as a supplement in an English-language newspaper; it is also available from today as a downloadable PDF on the Guardian’s website.

The List is not an artwork in itself – the art lies in its dissemination. Cennetoğlu always ensures that the look of the list remains the same – a grid of data, showing the year, the name of the refugee, where he or she came from, the cause of the death and the source.

The most recent version of the List was finished on 5 May 2018. Other material has been produced by Guardian journalists, using the List as a source, to report on how the shape of the refugee crisis has changed over the years.

The List is a stark depiction of the scale of the refugee crisis and the human suffering it has caused over the past 25 years – misery that seems to have no end in sight.

This edition of The List has been commissioned and produced by Chisenhale Gallery, London, and Liverpool Biennial in conjunction with Banu Cennetoğlu’s exhibition at Chisenhale Gallery (28 June-26 August) and as part of Liverpool Biennial of Contemporary Art (14 July-28 October).

Archive for category Refugees

Return to Za’atari

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 23, 2018

In 2016, researchers from the University of Sheffield went to Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan to work with the people who lived in the camps to help find innovative solutions to the practical problems they were facing. This was not about parachuting in experts to tell people what they should do. The people in the camp were the real experts, in terms of understanding what was needed, the resources they had at their disposal, and the constraints (the ban on creating any permanent structures, for example) on the solutions they implement.

This isn’t a one-way process. Because to solve the everyday problems in the camp they are working with, and not just for, the people in the camp.

Obviously not everyone living there has the kind of skills that can be pressed into service to help build the resources that the communities need, and not everyone is well and strong enough after the physical and mental traumas of flight to contribute in this way. But as a transit camp becomes a city the people living there can become again the people they were at home, can be part of the process of building and healing and problem-solving.

Innovative solutions to everyday problems are being developed, in collaboration with the people of Za’atari. Tony Ryan, the Director of the Centre, has been working with Helen Storey from the London College of Fashion, on resource use and repurposing in conflict zones, and on specific questions from the UNHCR about the design and manufacture of all kinds of things that we take for granted, like sanitary wear, make-up and bicycles. Resources are scarce in the camp, where 80,000 people share 6 sq km of space, and nothing is left to waste.

The team went back in 2018 to do some further work on these projects, and see the progress that had been made. Check out this presentation given by Professor Tony Ryan, Director of the Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures, showing some of the work his team has been involved with in the camp: 24H2018 Zaatari, as well as the film below.

The team went back in 2018 to do some further work on these projects, and see the progress that had been made. Check out this presentation given by Professor Tony Ryan, Director of the Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures, showing some of the work his team has been involved with in the camp: 24H2018 Zaatari, as well as the film below.

Make no mistake, the people who end up in these camps face daily struggles that many of us cannot imagine. But those I met embodied values that are often forgotten by those of us in more privileged parts of the world: an adaptable approach to solving problems, an aversion to waste, a sense of community. As hard as we must fight to live in a world where no one is forced to flee their home, there is much we can learn from Syria’s refugees.

Tony Ryan, Director of the Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures, University of Sheffield.

Refugee World Cup, Friday 22 June

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 22, 2018

Playing today: Nigeria, Brazil, Serbia, Switzerland, Costa Rica, Iceland

Nigeria

In 2018, the Nigerian refugee crisis is into its fifth year. Since extreme violent attacks of the Islamist sect Boko Haram spilled over the borders of north-eastern Nigeria into neighboring countries in 2014, Cameroon, Chad and Niger got drawn into a devastating regional conflict. To date, the Lake Chad Basin region is grappling with a complex humanitarian emergency. Some 2.2 million people are uprooted, including over 1.7 million internally displaced (IDPs) in north-eastern Nigeria, over 482,000 IDPs in Cameroon, Chad and Niger and over 203,000 refugees.

The crisis has been exacerbated by conflict-induced food insecurity and severe malnutrition, which have risen to critical levels in all four countries. Despite the efforts of Governments and humanitarian aid in 2017, some 4.5 million people remain food insecure and will depend on assistance. The challenges of protecting the displaced are compounded by a deteriorating security situation as well as socio-economic fragility, with communities in the Sahel region facing chronic poverty, a harsh climate, recurrent epidemics, poor infrastructure and limited access to basic services.

The Nigerian military, together with the Multinational Joint Task Force, have driven extremists from many of the areas they once controlled, but these gains have been overshadowed by an increase of Boko Haram attacks in neighbouring countries. Despite the return of Nigerian IDPs and refugees to accessible areas, the crisis remains acute.

Boko Haram may be the primary cause of flight from Nigeria but it is not the only current factor. In twelve northern states, Shari’a law imposes brutal penalties on alcohol consumption, homosexuality, infidelity and theft. More widely across the country, homosexual couples who marry face up to 14 years in prison, witnesses or those who help them ten years. The law punishes the “public show of same-sex amorous relationships directly or indirectly” with ten years in prison, and mandates 10 years in prison for those found guilty of organising, operating or supporting gay clubs, organizations and meetings.

In 1966, Igbo people fled the North after a series of coups and counter-coups led to massacres in Kano, Zaria and other northern cities.

Brazil

According to the Forced Migration Observatory, a new database from the Brazilian think tank Instituto Igarapé, … hundreds of thousands of Brazilians are driven from their homes each year by disasters, development and violent crime. Venezuelans escaping economic crisis at home are also pouring into Brazil. Though neighboring Colombia has born the brunt of this exodus – welcoming as many as 1 million migrants since 2015 – Brazil has seen some 60,000 Venezuelans arrive and numbers are rising fast.

Despite this influx, Brazil’s main migrant problem remains the millions of displaced people already inside its borders. This domestic crisis has mostly simmered under the radar for nearly two decades.

Serbia

As a result of the arrival of large numbers of people into southern Europe that accelerated two years ago this month, there are 7,600 refugees in Serbia, according to the UN refugee agency (UNHCR). Most live in 18 state-run asylum centres that provide basic necessities. Many are starting to prepare for the long haul. … Meanwhile, every weekday, five people are chosen to leave Serbia and enter Hungary – and the EU – legally. It may be a double-edged sword. “In Hungary my family are in a 24-hour closed camp – when someone goes to the bathroom there are four police on every side of you,” said Weesa “They are not free like we are here.” Faqirzada says many countries could learn a lot from Serbia. “In Afghanistan, no one cares for each other. In Turkey there were no schools. In Bulgaria we slept in forests. But in Serbia, the people support each other. They support my family too, I do not forget this.” Still, if and when the Faqirzada family are given a chance to move closer to Germany, they will take it.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/08/eu-refugees-serbia-afghanistan-taliban

The Kosovo War caused 862,979 Albanian refugees who were either expelled by Serb forces or fled from the battle front. In addition, several hundreds of thousands were internally displaced, which means that, according to the OSCE, almost 90% of all Albanians were displaced from their homes in Kosovo by June 1999. After the end of the war, Albanians returned, but over 200,000 Serbs, Romani and other non-Albanians fled Kosovo. By the end of 2000, Serbia thus became the host of 700,000 Serb refugees or internally displaced from Kosovo, Croatia and Bosnia.

Switzerland

During World War II, Switzerland as a neutral neighbour was an obvious choice of destination for refugees from Germany and France in particular. Switzerland’s longstanding neutral stance had also involved a pledge to be an asylum for any discriminated groups in Europe – Huguenots who fled from France in the 16th century, and many liberals, socialists and anarchists from all over Europe in the 19th century. However, Swiss border regulations were tightened in order to avoid provoking an invasion by Nazi forces. They did establish internment camps which housed 200,000 refugees, of which 20,000 were Jewish. But the Swiss government taxed the Swiss Jewish community for any Jewish refugees allowed to enter the country. In 1942 alone, over 30,000 Jews were denied entrance into Switzerland.

The closure of the popular migration route via the Balkans border in March 2016, led to a rapid increase in the number of refugees in Switzerland as they immigrated to Germany. Refugees entered Switzerland through Ticino, and a report estimated there were 5,760 illegal residents in this region.

Amnesty International reported that migrants and asylum-seekers with rejected asylum claims were returned in violation of the non-refoulement principle [a fundamental principle of international law that forbids a country receiving asylum seekers from returning them to a country in which they would be in likely danger of persecution based on “race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion]. Concerns remained regarding the use of disproportionate force during the deportation of migrants. Government proposals for the creation of a National Human Rights Institution continued to be criticized for failing to guarantee the Institution’s independence.

Costa Rica

4,471 asylum applications by refugees were received in 2016 in Costa Rica – according to UNHCR. Most of them came from El Salvador, Venezuela and from Colombia. A total of 2,815 decisions were made on initial applications, of which 81 per cent were initially rejected. Violence in El Salvador and Honduras is causing refugees to arrive in increasing numbers.

Because they’re often escaping severe violence in their countries of origin, they often need greater psycho-social assistance to address mental health needs. A lack of local support networks means they require more material and economic assistance than other groups, too.

As in other contexts, refugees in Costa Rica face barriers that prevent them from fully exercising their rights: discrimination, xenophobia, and a lack of information (either on their side or from the host community). Unlike many places hosting displaced populations, however, refugees and asylum seekers in Costa Rica have the right to work, start their own businesses, open bank accounts, and access public services (health care, education, etc.). Understanding this context is critical to counteracting barriers, easing local integration, and increasing self-reliance. UNHCR identifies individuals and families living in the most vulnerable conditions and addresses their immediate needs. Then, to empower households to build new economic and social lives and better integrate into their host countries, they’re included in the Graduation program.

To encourage this integration and address extreme poverty faced by Costa Rican households, several women from local communities are included in the project. Most are survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, single mothers in highly vulnerable conditions, or HIV positive. Not only does this provide vulnerable women from Costa Rica with a pathway out of poverty, it also enhances the self-reliance and community integration of refugee women and children by connecting them to a similarly vulnerable local community of women.

Since Iceland’s refugee policy was first initiated in 1956, the country has accepted a grand total of 584 refugees, a rate lower than other Nordic countries. Groups and families of refugees have arrived from a diverse range of countries — Vietnam, Poland, Hungary, former Yugoslavia and Serbia. Post-recession, Iceland’s economy has recovered at a four percent growth rate per year. However, according to a PBS report, Iceland would require 2,000 new immigrants a year to maintain that level of growth — refugees would contribute to this number. The Mayor of Akureyri, Eirikur Bjorgvinsson, explains that refugees contribute more to Iceland’s economy than the amount of assistance that they are actually receiving. In order to become assimilated in Iceland society, the government offers financial assistance, education, health services, housing, furniture and a telephone for up to one year to refugees in Iceland. According to the Ministry of Welfare, the policy in Iceland has welcomed a quota of 25 to 30 refugees every year. However, this quota has changed in the last few years with the crisis in Syria, protests from Icelandic citizens and an exception in 1999 with the outbreak of the war in Kosovo.

In the next few weeks 52 new refugees are expected to arrive to Iceland, as reported by Vísir.is. Most of them are children and young adults under the age of 24. Last August, the Icelandic government agreed to welcome 55 refugees. As we reported last year, however, a Market and Media Research poll on the subject showed that 88.5% of Icelanders believe the government should welcome more of them.

The 52 refugees who are on their way to Iceland are mostly of Syrian, Iraqi and Ugandan origin. While the Syrian and Iraqi have lately been residing in refugee camps in Jordania, those coming from Uganda were forced to seek asylum away from their home country because of their non-normative sexuality (Iceland has been accepting queer refugees since 2015).

Upon arrival they will be sent to different parts of the country: 4 families are going to the Fjarðabyggð municipality in the east, 5 families to the Westfjords peninsula in the North and 10 individuals will stay in Mosfellsbær, close to Reykjavik.

The Minister of Social Affairs Ásmundur Einar Dádason assured that the preparations to receive the refugees are in full swing. “The results have been positive so far and we received applications from the municipalities to participate in the program,” he said. “It’s a very good example of a solid partnership between the state, the local authorities and the Red Cross.”

https://grapevine.is/news/2018/02/09/52-refugees-on-their-way-to-iceland/

Naming the Dead: The List

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 22, 2018

Over the last few years I’ve tried to post after terrorist atrocities and mass shootings the names, not of the perpetrators, but of the victims. It’s the same principle that informs so many projects arising out of the Holocaust and other genocides, of restoring to the dead something of who they were, in the face of their dehumanisation.

The refugees who have died attempting to find a new home in Europe, driven from their own homes by brutal war, terrorism and desperate poverty, deserve no less. But we know so few of their names.

On World Refugee Day (20 June) The Guardian published The List. It goes back to 1993, when Kimpua Nsimba, a 24 year old refugee from Zaire, was found hanged in a detention centre, five days after arriving in the UK. It’s the work of United for Intercultural Action, a European network of 550 anti-racist organisations in 48 countries.

It lists only those whose deaths have been reported – 34,361 of them. The total is almost certainly much higher than that. Many simply disappear.

Goma, Budumbura, Za’atari

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 21, 2018

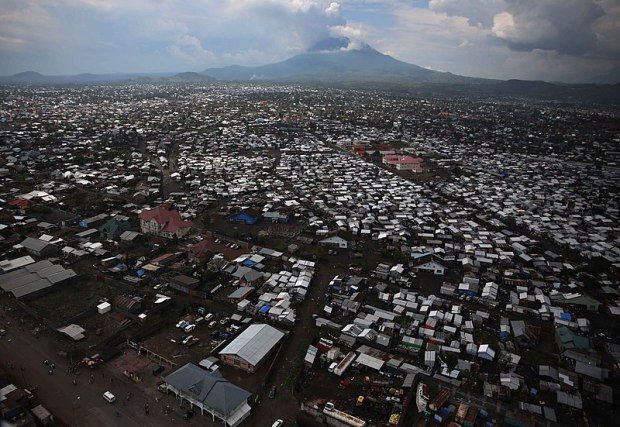

Refugee camps, meant to be temporary, transitional spaces, emergency places of shelter, have become cities. Their populations have grown, and have remained, nowhere else for them to go.

For Refugee Week 2013, I wrote about the camp in Goma, in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The refugee camp is a liminal space. Like a border or no-man’s land, it is a place through which people pass, but not a place where they should live. It is a between-space – between the place from which the refugees fled and the place of safety which they hope to reach (which may, of course, be the place from which they fled, if conditions and circumstances have changed). The camp’s inhabitants are uncitizens, marginalised and separated both from their former home and from the country in which the camp sits. It’s a waiting zone where nothing can be fully brought to fruition, a place of quarantine. Is it purgatory – a place of temporary suffering, though without the promise of paradise to come? Or limbo – the first circle of Dante’s Hell?

Goma is, arguably, a particularly grim example, given the circumstances in which it arose. The refugees from Rwanda which it housed included many who had participated in the genocide of 1994, as well as those who had tried to escape it. The humanitarian efforts to feed and support the people in the camps thus ran into controversy – were our charitable donations feeding murderers, or their victims? Certainly the camps were used as a base for Hutu militia to attack Tutsis and make forays into Rwanda. Today the continuing volatility and violence endemic in DRC continue to make Goma a dangerous place for its inhabitants, especially the children. But a return home is fraught with difficulties and dangers too.

Goma is, arguably, a particularly grim example, given the circumstances in which it arose. The refugees from Rwanda which it housed included many who had participated in the genocide of 1994, as well as those who had tried to escape it. The humanitarian efforts to feed and support the people in the camps thus ran into controversy – were our charitable donations feeding murderers, or their victims? Certainly the camps were used as a base for Hutu militia to attack Tutsis and make forays into Rwanda. Today the continuing volatility and violence endemic in DRC continue to make Goma a dangerous place for its inhabitants, especially the children. But a return home is fraught with difficulties and dangers too.

In Ghana, the Buduburam refugee camp has been in place since the start of the first Liberian Civil War in 1989, and accommodates refugees from this conflict, from the second Liberian Civil War, and the civil war in Sierra Leone. Both of those countries are now peaceful and stable, and there is pressure to encourage residents to return home, or seek permanent settlement elsewhere. Some parts of the camp have been closed, and residents displaced, amid claims that many living there are not part of the original refugee communities and/or do not meet the criteria for refugee status. For those who have lived here since the beginning, who have grown up here, raised families here, the future may look uncertain, but it would seem there are options and possibilities.

If there is a camp that embodies the current refugee crisis, it is Za’atari, in Jordan.

Home to 80,000 people. Intended as a temporary, transitory place, but evolving in to a long-term home for so many displaced by war. It’s Jordan’s fourth biggest city. Seen from above, as it is often is, to emphasise its sprawling scale, it’s easy to forget that in that city, as in any city, people are living their lives.

We use the refugee camp as a symbol of the challenge of mass migration, and of the desperate needs of those who live there. The people who did, once, lead lives very much like our own, until war drove them out. They were farmers, teachers, lawyers, engineers, nurses and builders. They still can be.

Within the camp, babies are born, children grow up, people get sick, women have periods, all of the normal events of life take place here too. All of these things present greater challenges when you’re living in a place that wasn’t intended to be a city, that was only meant to house you for a short time, until you could safely go home, or until some other place was found for you to move on to.

If Goma represents despair and Buduburam uncertainty, Za’atari can be a place of hope and of inspiration. It’s a place where the inhabitants put to use not only the limited physical resources available to them but the abundance of creativity, ingenuity and energy to solve the day to day problems, to provide for themselves not just today but in the longer term.

Most people in refugee camps would rather be at home. But if the place they called home is still a war zone, the street they lived on is rubble, the schools and hospitals and infrastructure of their city destroyed, going home is a dream for the future, not an option for now. So meantime people make new communities in these temporary places. They use their skills and knowledge to make the place better, safer, more comfortable, to make limited resources go further. It’s not home, but it can be a home.

UNHCR wants to find alternatives to camps.

The possible alternatives are diverse and affected by factors such as culture, legislation and national policies. Refugees might live on land or housing which they rent, own or occupy informally, or they may have private hosting arrangements. Such alternatives typically allow refugees to exercise their rights and freedoms, make meaningful choices about issues affecting their lives, contribute to their community and live with greater dignity and independence.

UNHCR recognizes that enabling refugees to live in communities lawfully, peacefully and without harassment – in urban or rural areas – supports their ability to take responsibility for their lives and communities. Refugees bring personal skills and assets which can benefit the communities where they are living. They also bring the qualities of perseverance, flexibility and adaptability. Refugees who maintain their spirit of independence, use their skills and develop sustainable livelihoods during displacement, will be more resilient and better able to overcome future challenges.

So our shared responsibility, as citizens of the world, is to seek a future where people do not have to leave their homes in fear of their lives, but at the same time to recognise that war, famine and oppression will continue to force migration of peoples and to find better solutions than we have at present for enabling those people to build a future.

Refugee World Cup, Thursday 21 June

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 21, 2018

Playing today: Denmark, France, Croatia, Argentina, Australia, Peru

Denmark

Denmark has had a clear and consistent message to asylum seekers in the last two years: stay away. The latest figures on the number of people seeking asylum in the country suggests that message has finally sunk in.

Denmark received just 3,458 asylum applications in 2017—an 84% drop from 2015 (when the refugee crisis saw a dramatic peak in the number of asylum seekers in Europe). The government puts the drop down to the 67 anti-immigrant (link in Danish) regulations it has passed since 2015.

https://qz.com/1171331/asylum-seekers-in-denmark-number-of-applications-has-fallen-by-84-since-2015/

On October 1, 1943, Adolf Hitler ordered Danish Jews to be arrested and deported. The Danish resistance movement, with the assistance of many ordinary Danish citizens, managed to evacuate 7,220 of Denmark’s 7,800 Jews, plus 686 non-Jewish spouses, by sea to nearby neutral Sweden. The vast majority of Denmark’s Jewish population thus avoided capture by the Nazis and is considered to be one of the largest actions of collective resistance to aggression in the countries occupied by Nazi Germany. As a result of the rescue, and the following Danish intercession on behalf of the 464 Danish Jews who were captured and deported to the Theresienstadt transit camp, over 99% of Denmark’s Jewish population survived the Holocaust.

Denmark received about 240,000 refugees from Germany and other countries after World War II. They were put into camps guarded by the reestablished army. Contact between Danes and the refugees were very limited and strictly enforced. About 17,000 died in the camps caused either by injuries and illness as a result of their escape from Germany or the poor conditions in the camps.

France

Hundreds of refugees are living in “inhumane” conditions in northern France with no toilets and only polluted rivers to wash in, the United Nations (UN) has warned. “Increasingly regressive migration policies” and a lack of attention from national and international authorities has led to hundreds of displaced people living without adequate emergency shelter or proper access to drinking water in Calais and Dunkirk, experts said. It is estimated that up to 900 migrants and asylum-seekers are currently based in Calais, 350 in Dunkirk and an unidentified number at other sites elsewhere along the northern French coast. The French government has in recent months, taken temporary steps to provide access to emergency shelter, drinking water and sanitation for some refugees. Up to 200 migrants are currently being put up at a sports centre in Dunkirk. But the UN experts stressed that these were not long-term solutions and warned that there was an absence of valid alternatives in the provision of adequate housing.

The Nazi invasion of France led to an initial panicked flood of refugees – some 6-10m people took to the roads, with little idea of where they might go, carrying what they could. Many subsequently returned home, deterred by the chaos on the roads, the collapse of public transport, and the difficulties of finding somewhere to live and earn a living. Increasingly Jews in France, as well as political opponents of Nazism, sought routes out of the country. Initially they headed to the ‘unoccupied zone’, governed (on paper at least) by the Vichy government under Marshal Petain. Many tried to cross the border into Switzerland, but were often turned back by zealous border guards. Those who could cross to Spain headed to Portugal, where they hoped to get on a ship in Lisbon. Would-be refugees often paid a high price to guides who claimed they could get them to safety – some were cheated, some betrayed, but some did get through.

Croatia

Croatia declared its independence from the former Yugoslavia in 1991. This resulted in a war that lasted until 1995. During this time, 900,000 Croats were displaced both inside and outside the country. An estimated that between 200,000-300,000 ethnic Serbs left Croatia in August 1995, while 130,000 ethnic Croats left Bosnia and Herzegovina for Croatia. War broke out in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992. During the war, an estimated 403,000 refugees arrived in Croatia as a result of the conflict. The Croatian refugees who left the country began returning in 1996. By 2012, roughly half of the Croatian refugees of Serbian descent had returned to Croatia. One of the main issues impeding their return was housing.

In 2015, Croatia faced new refugee challenges when a huge wave of Syrian refugees arrived en route to northern Europe. During this influx, more than 800,000 people passed through Croatia. Two refugee camps were set up in Croatia, and the government provided free transport for refugees to Hungary and later to Slovenia. On September 16, 2015, Croatia became one of the main transit countries when Hungary closed its borders to refugees. Since then, the country sees approximately 12,000 entries each day.

Argentina

High wages, economic prosperity, a good public education system and a liberal legal framework brought many European immigrants to Argentina between 1870 and 1914. By the start of World War I, Argentina was one-third European. However, by the end of 1960, most European migration to Argentina halted. In light of subsequent high levels of regional migration, Argentina signed a regional agreement, along with Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela, which recognizes the right to migrate, provides equal treatment for foreigners and the right to family reunification. It also established the “Patria Grande” program, granting residency and creating a process for foreigners to become permanent residents. Argentina signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the UNHCR in 2005, dictating the guidelines for the admission of refugees in Argentina. Among the criteria for resettlement in Argentina are that immigrants are survivors of torture or violence, women at risk, or women with children or families with strong integration potential. Before refugees in Argentina are considered for visas, relatives or other Argentinian citizens must vouch for them. The process kicks off with a letter of invitation sent to the refugee family. In July 2016, Argentina announced it would accept 3,000 Syrian refugees, the first country to assist the European Union with the Syrian refugee crisis.

Australia

For years, Australia has been punishing people who need our protection. We have been turning back the boats which were carrying them to safety, and shipping and warehousing them in Nauru and Papua New Guinea. If they make it to mainland Australia, we have been detaining them indefinitely and, once they are released, leaving them to struggle in the community without support. … The kinds of services and supports available to people seeking asylum change depending on how and when they came to Australia, the stage of the process they are in, and the visas they have (or did have). Services and supports also vary between and within States and Territories. Even then, the conditions of their visas (if any) often seem arbitrary, and there is little to no transparency in decision-making. On top of this, there are frequent, often unannounced, changes to people’s eligibility for services and supports. In 2018, more policy changes are likely to leave thousands more without any income or government-funded support. As well, policies that punished people seeking asylum increasingly apply to those who came by plane, as well as by boat. These changes add to existing policies that are already driving thousands of people to destitution. Every day, more and more people needing our protection are forced to rely on overstretched and overwhelmed communities and non-governmental organisations to survive. … People who need our protection should not be punished for seeking it. They should not be forced to choose between starving in the streets or returning home to persecution. They should not be treated as if they are not human, simply because they are not (yet) Australian.

https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/publications/reports/with-empty-hands-destitution/

Peru

In the ’80s, Maoist terrorist group, Sendero Luminoso, waged a brutal war against the government. Gross human rights violations committed by both parties destabilized the country and left half a million people internally displaced. Many of Peru’s poorest people are refugees from the civil war who lost everything they owned after leaving the countryside and never recovered. Environmental changes, such as drought and shortened growing seasons, have caused a wave of “climate refugees” in Peru. Although Peru has its own challenges of adequately settling internally displaced people, it has opened its doors to neighbors both near and far with initiatives to streamline processes to receive Syrian refugees and the creation of nearly 6,000 visas for Venezuelans to escape the current crisis.

Refugee World Cup,Wednesday 20 June

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 20, 2018

Playing today: Uruguay, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Spain, Portugal, Morocco

Uruguay was the first Latin American country to offer sanctuary to Syrian refugees. However, the country’s struggling economy made it impossible to assimilate the new arrivals into the workforce, and the welcome rapidly began to sour, with some refugees attempting to move on to other countries, but finding difficulty in doing so because most countries do not accept their Uruguay-issued documentation and without their Syrian-issued passports.

Saudi Arabia has faced international criticism for its failure to take in numbers of Syrian refugees proportionate to its resources, whilst poorer neighbours struggle to support the influx. The UNHCR says there are between 100,000 and 500,000 refugees in the country against a Saudi population of 31 million. One significant reason is that a majority of the refugees fleeing to Saudi Arabia are from Sunni areas of Syria – areas that play host to the Islamic State. Saudi Arabian forces have bombed these regions and want to know if the refugees are escaping ISIS or the bombings. Meanwhile Saudi intervention in the Yemeni Civil War has contributed to the flow of refugees out of the country.

Iran has taken on a significant role in providing sanctuary for refugees in the region, particularly from Afghanistan and Iraq. During the Second World War, it took in Polish refugees – both soldiers and civilians. On March 19, 1942, General Władysław Anders ordered the evacuation of Polish soldiers and civilians who lived next to army camps. 33,069 soldiers left the Soviet Union for Iran, as well as 10,789 civilians, including 3,100 children, a small fraction of the approximately 1.7 million Polish citizens who had been arrested by the Soviets at the beginning of the war. Polish soldiers and civilians stayed in Iranian camps at Pahlevi and Mashhad, as well as Tehran.

Spain

Franco’s 1939 victory in the Spanish Civil War saw desperate refugees from the Republican side trying to leave Spain. London and Paris were disinclined to accept them, but Mexico was prepared to accept all Spanish refugees then in France, and placed them under diplomatic protection.

Early in the Civil War, child refugees were shipped to Britain, Belgium, the Soviet Union, other European countries and Mexico. Those in Western European countries were able to return to their families after the war, but those in the Soviet Union, from Communist families, were forbidden to return until 1956, after Stalin’s death. They lived in Soviet orphanages and were regularly transferred from one orphanage to another according to the progress of the Second World War. Just under 4,000 children arrived at Southampton Docks on 23 May 1937. All the children and accompanying adults were housed in a single, large refugee camp in North Stoneham, near Southampton.

Early in the Civil War, child refugees were shipped to Britain, Belgium, the Soviet Union, other European countries and Mexico. Those in Western European countries were able to return to their families after the war, but those in the Soviet Union, from Communist families, were forbidden to return until 1956, after Stalin’s death. They lived in Soviet orphanages and were regularly transferred from one orphanage to another according to the progress of the Second World War. Just under 4,000 children arrived at Southampton Docks on 23 May 1937. All the children and accompanying adults were housed in a single, large refugee camp in North Stoneham, near Southampton.

During World War II, Portugal, which remained neutral, attracted around 100,000 to 1,000,000 refugees. “In 1940 Lisbon, happiness was staged so that God could believe it still existed,” wrote the French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. The Portuguese capital became a symbol of hope for many refugees. Even Ilsa and Rick, the star-crossed lovers in the film Casablanca, sought a ticket to that “great embarkation point”. Erich Maria Remarque’s 1964 novel, The Night in Lisbon, told the story of two German refugees in the city in the opening months of the war.

In 1976, Morocco laid claim to the Western Sahara, an area south of Morocco, after Spain withdrew from the territory. This action incited a decades-long war between Morocco and the Polisario Front, Western Sahara’s liberation movement, that lasted until 1991 when the United Nations brokered a cease-fire. The suspension of hostilities left Morocco with de facto control over two-thirds of Western Sahara. As a result, thousands of refugees from Western Sahara fled to Tindouf, Algeria. An estimated 90,000 Western Saharan refugees remain in camps in Tindouf, Algeria because a referendum to vote on the independence of Western Sahara from Morocco — promised in the 1991 UN cease-fire — has yet to occur. Morocco has received an influx of refugees since the start of the Syrian civil war – UNHCR estimates that more than half of the 6,000 refugees and asylum-seekers currently in Morocco are from Syria.

Suffer the little children…

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees, Second World War, USA on June 20, 2018

I don’t want to do that whole ‘as a parent’ thing. It’s offensive to all the people who aren’t parents but who do give a damn (most people, I’d like to think, though it’s harder to believe that some days than others) to suggest that if you’ve never given birth or fathered a child you could contemplate with equanimity cruelty against the most vulnerable people, the people we are all, parents or otherwise, programmed to protect, the people who are our collective future.

It’s the 80th anniversary this year of the Kindertransport, when parents in fear of the future sent their children off into what they could not know would be a safer future, into the arms of strangers. Most of those children never saw their parents again. That window of opportunity was open so briefly – from the point where enough people realised the danger to the point when the borders slammed shut – and those who missed it, in many cases, were murdered. The children were undoubtedly saved, but they were not unmarked by that early separation (even those who were reunited with their parents post-war found themselves and their parents irrevocably changed by what had happened in those years).

I wrote about the Kindertransport in a previous Refugee Week blog. I’ve returned again and again to the vulnerability of children and to our shared responsibility to protect them.

Children are resilient, they’re tougher than you’d think, as all parents remind themselves on a regular basis. But how do those early experiences, that exposure to death and danger and horror, affect them as they grow? We can draw upon the stories of an earlier generation of children whose parents entrusted them to strangers, to be transported across Europe and to be taken into the homes of other strangers, to be kept safe, in the hope of a reunion that for many was never to happen. We know of the confusion that many of them felt, about their past, their identity (not all Jewish children were fostered in Jewish homes); and of the trauma of separation from parents and family, and in so many cases, of the discovery post-war that parents and family had been swallowed up in the barbarity and were lost to them for ever.

No one claims an exact equivalence between the circumstances in Nazi Europe and those we face now. But equally no one would doubt that in desperate circumstances children are the most vulnerable, least able to defend themselves, most open to abuse.

It is often asked, below the line, what kind of parents would abandon their children to such a fate. Firstly, it is a huge assumption that these children have been abandoned. Many will be orphaned. Many will have become separated from their parents in the chaos of flight. And some parents, faced with the desperate choice to save some but not all of the family will have chosen to send their children on to at least the chance of safety, as those parents did 80 years ago.

It’s also often claimed that the children are a sort of Trojan horse – if we allow our hearts to soften and give them sanctuary here, their parents and older siblings will then emerge from the shadows and demand to join them. Or that they are not in fact minors, just young-looking adults. It takes a particularly determined brand of cynicism to look at these children in such need and see only threat and deceit.

Most of us will see instead both vulnerability and potential. If we take them in we can both protect them from the dangers they currently face, and allow them to fulfil the potential they have, to contribute to the country and the community that gives them sanctuary.

And today, how can we even talk about the children of the Kindertransport, the children crossing the Med in flight from war and terror, without talking about the children whose parents have tried to cross the border in hope of a better future and who are now caged, terrified, comfortless?

Don’t tell me those parents are ‘illegals’, lawbreakers. Lawbreakers can be dealt with humanely. Children are not lawbreakers. And no human being is an alien, an illegal. It’s not so many steps from that approach to the approach that condemned Native American children, Tutsi children, Jewish children to death because of their heritage. And the rhetoric from the White House takes us ever closer. Animals. Vermin. Infestation. We have to call this out, all of us. And especially when brutal policies are justified by quoting the Bible.

I know these children are unlikely to meet the legal definition of refugees. But how we treat the most vulnerable surely must define our values as a society. There is another, better America. There are other, better ways of dealing with migration and asylum. We have to find them.

To quote Sir Nicholas Winton, who himself was responsible for saving around 700 children from Nazi Europe, ‘If it’s not impossible, there must be a way to do it’.

With the resources we have, collectively, it’s not impossible. It can’t be.

Refugee World Cup, Tuesday 19 June

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 19, 2018

Playing today: Russia, Japan, Egypt, Senegal, Colombia, Poland

Russia since the late nineteenth century has contributed massively to the forced migration of peoples. From Jews driven out of Tsarist Russia by pogroms, to political refugees from Stalin and his successors, and the displacement of populations due to civil and world wars, Russian refugees have made a significant cultural impact on the countries in which they found sanctuary. Writer Vladimir Nabokov and artist Marc Chagall both fled to Europe and then had to seek safety in the USA as the Nazis took over. In France, Irene Nemirovsky established a successful literary career but was deported to Auschwitz where she was murdered. In recent times, Russia has seen an influx of refugees from Ukraine and from Syria.

Japan

In 2011, a catastrophic earthquake and tsunami struck Japan, killing over 15.5k people, causing a serious nuclear accident, and creating over 300k internal refugees.

Japan accepted just 20 asylum seekers last year – despite a record 19,628 applications – drawing accusations that the country is unfairly closing its door on people in genuine need. Since 2010, Japan has granted work permits to asylum seekers with valid visas to work while their refugee claims were reviewed, a change the government says has fuelled a dramatic rise in “bogus” applications from people who are simply seeking work. According to figures released this week, the number of applicants in 2017 rose 80% from a year earlier, when 28 out of almost 11,000 requests were recognised. … Recent changes indicate Japan is getting even tougher. In an attempt to reduce the number of applicants, the government last month started limiting the right to work only to those it regards as genuine asylum seekers. Repeat applicants, and those who fail initial screenings, risk being held in immigration detention centres after their permission to stay in Japan expires.

Eri Ishikawa, head of the Japan Association for Refugees, said the new regulation was part of a wider crackdown on refugees under the conservative prime minister, Shinzo Abe.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/feb/16/japan-asylum-applications-2017-accepted-20

Egypt

Egypt is a destination and transit country for refugees and asylum-seekers, most of whom live in urban areas. According to UNHCR, currently, 208,398 refugees and asylum-seekers of 63 different nationalities are registered with UNHCR Egypt. Over half are from Syria.

But refugees in Egypt also face similar dangers compared to the perils reported from other North African countries. In September 2016, a ship capsized off the Egyptian coast, with more than 400 migrants on board. The boat had Egyptian, Sudanese, Eritrean and Somali migrants on board and was believed to be heading to Italy. 168 migrants were killed. This tragedy, however, did not slow down or stop the flow of refugees trying to make it to Europe. According to Mada Masr, an Egyptian news outlet, Eritrean refugees, for example, are staying in Cairo’s Mohandiseen district, waiting to get on boats to Europe. Eritreans are increasingly using Egypt as a transit country instead of going through Libya.

According to the EU, 7 percent of migrants who came to Europe in 2016 came through Egypt. The UNHCR explains: “limited livelihood opportunities and a lack of prospects for integration, coupled with a loss of hope to be able to return to their country of origin have contributed to the steady rise in the numbers of refugees departing irregularly by sea.”

Dangers lurk not only at sea but also in the desert. Between 2009 and 2014, hundreds of refugees were held hostage by Bedouin tribes in the Sinai. The refugees, coming from countries like Eritrea and Ethiopia, would be abducted to demand bribes of $20,000 to $40,000.

Meanwhile in 2012, Israel constructed a fence on the border with Egypt to keep out African migrants.

http://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/5244/how-is-egypt-as-a-country-for-refugees

2004 marked the beginning of the most significant violent conflict in Senegal’s recent history. The province of Casamance has been seeking independence from the Senegalese government since 1982. Civil unrest came to a head in 2004, with instances of violent conflict being documented well into 2014. The conflict has displaced thousands and taken a serious toll on civilian life. While a ceasefire was signed in 2014, smaller scale fighting continues today, albeit at a much smaller scale. According to the most recent figures, there are an estimated 62,638 internally displaced people (IDP) in and around Senegal as a result of this civil strife. Senegal also hosts refugees from CAR, Ivory Coast, Gambia and Mauritania.

In March 2018, Colombia hosted 277 refugees, 625 asylum-seekers and 11 stateless people. There are 7,671,124 internally displaced people, Colombians who have been forced to flee their homes but have not sought safety in another country, the second highest total worldwide (only Syria has a greater number).

The peace agreement between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) is being implemented and the former guerrilla group has officially laid down its arms. However, clashes with other armed groups have persisted and forced displacement is expected to continue in some areas.

Whilst refugees from Colombia’s own conflicts have headed to Ecuador, Venezuela or Panama, at least one million people have entered Colombia from Venezuela since President Nicolás Maduro’s government descended into crisis last year.

Poland

Later in Refugee Week I will be posting the story of Barbara Szablewski (nee Czerniajew) and her life as a refugee during World War II.

Poland’s history is of invasions and partitions and displacement of peoples. Before Hitler turned on his ally Stalin, they had divided the country up between them, and Poles suffered under both regimes. Some found sanctuary in the UK where many joined the fight against Hitler and after the war settled permanently rather than return to a country which had replaced one tyranny for another.

Poland today, like so many European nations, is resisting the call to welcome refugees. The government has refused to meet the EU’s mandatory refugee quota and take in refugees from the Middle East. The country is one of the most homogeneous in Europe, partly as a result of the Holocaust’s destruction of its Jewish population and the post-war relocation of its large Ukrainian, Belarusian, German and other minorities.

Bishop Tadeusz Pieronek, from the more liberal wing of the Church, told the Rzeczpospolita newspaper that accepting a few hundred asylum seekers isn’t much of a problem for a country of 38 million. “Not accepting refugees practically means resigning from being a Christian,” he said. “I’m ashamed of those who don’t want to do their duty not just as Christians but as human beings.” Critics also point out that Poles were massive beneficiaries of refugee policies in the past when thousands of people fleeing the military regime in the early 1980s were allowed to settle in Western Europe.

But the government, whose top officials are ostentatiously pious and which finds strong backing from the conservative wing of the Church, is no more willing to listen to the admonishments of Rome than of Brussels.

Free to be me

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 19, 2018

One of my first Refugee Week blogs, back in 2012, explored the double jeopardy experienced by people who were seeking sanctuary because their sexuality put them at risk of violence, imprisonment or murder in their homeland.

So, if the gay asylum seeker conforms to the norms of mainstream society, they may not convince officialdom that they are genuinely in need of asylum because of their sexuality. If they conform to officialdom’s expectations of gay identity, they put themselves in even greater danger should their claim fail and they be deported, and they expose themselves to prejudice and aggression here – most poignantly, the communities which for many asylum seekers provide a vital support network, their compatriots in exile, may be the most hostile. Double jeopardy.

It would seem that, not only have things not significantly improved for gay asylum-seekers in the last six years, but that they have worsened. The culture of disbelief is such that even those who are ‘out’ here may have their claim doubted because, for example, back home they married and had children. The level of risk that they might face back home is trivialised (they used to be told that they just had to be ‘discreet’ – maybe they still are…). And the fact that being ‘out’ here, being part of LGBT activism and campaigning, means that not only will they be at risk from the family members and neighbours who drove them out in the first place, but from anyone who knows from social media or the press about their case, is disregarded. Nonetheless:

According to Home Office figures released last year, of 3,535 asylum claims related to sexuality over a two-year period, a staggering two-thirds were rejected.

Things may have progressed here in a way that would have been unimaginable when I was a teenager in the 70s. That’s true, and wonderful. But LGBT people are still subject to random violence and public hostility, as this recent blog by Justin Myers pointed out:

So it is back, the self-consciousness of my youth, the reluctance to be myself, because being myself is not enough for some and not allowed by others. I can be visible, sure, but I can never be effervescent, or extra, or take up too much space, make too much noise. In a world where you can be abused in a pub for just being, what hope do we have?

And this is the fear I fear the most, because it’s the most powerful, merciless and controlling. When you take away my feeling of comfort and safety, I have nothing.

Imagine how that is amplified if you’re black, if you’re far from home, if your accent or your unfamiliarity with the language and culture here betrays your foreignness every time you venture out. Imagine living with that fear, if the only alternative you have is to go back to a place where violence and hostility are not just a risk but a certainty.

Owen Jones‘ piece in the Guardian is powerful and essential:

The architects of the British empire helped construct anti-gay laws across the globe that still endure today. The victims of such persecution need our support. Instead, they are being terrorised. It is a national scandal – and the silence over it must end.

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/01/forgotten-twice-lgbt-refugees/

Refugee World Cup, Monday 18 June

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 18, 2018

Playing today: Sweden, South Korea, Belgium, Panama, Tunisia, England

Panama hosts thousands of refugees seeking asylum from nearby countries such as Nicaragua and Venezuela. However, the majority of refugees in Panama come from Colombia. Over more than 50 years of drug-related conflict, 6.6 million Colombians have been forced to leave their homes. An estimated 370,000 Colombian refugees live in countries near their own, and Panama is a major hub.

Sweden has a reputation for generosity when it comes to asylum. But, as with many European countries, the mood is now less welcoming, and a recent poll suggested that 60% of voters want the country to take in fewer refugees. The most populous country in northern Europe, Sweden received 22k asylum seekers in 2017, and granted protection to 26.8k. Its reputation as a place of sanctuary goes back to World War II, when as an officially neutral nation which in various ways worked with both sides, it became a place of refuge for many who were fleeing Nazi persecution. Nearly all of Denmark’s 8,000 Jews were brought to Sweden as were Jews from Norway and Finland.

The Korean War caused a massive displacement of people in both North and South that left many thousands of Koreans in need of new homes. The close military, political, and economic ties between the United States and South Korea’s government during and after the war facilitated the immigration of large numbers of Korean war refugees, war brides, and war orphans to America.

South Korea is currently one of the few countries in Asia to be a party to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol. However, it continues to reject the vast majority of non-North Korean asylum seekers entering the country.

Since 1994, the government granted refugee status to approximately 2.5 percent of non-North Korean asylum applicants it screened. Between January and October 2017, 7,291 applied for refugee status; the government accepted just 96 cases, or approximately 1.31 percent of applications. North Koreans do not apply for asylum through this process, they are granted South Koran citizenship through the Promotion and Resettlement Support Act for North Korean Refugees.

The number of North Koreans arriving in South Korea has decreased significantly, because of heightened security on both sides of the border. Some arrive in the South via China or Mongolia. 85% of North Korean refugees are women. Upon arrival all North Korean refugees have to go through lengthy interrogation. Many are traumatised, and find the process of integration painful and difficult.

Tunisia has seen the number of refugees increase greatly since 2011, and then decrease to a much smaller number today. The country’s location attracts both migrants and refugees. It has promised to adopt a national asylum law soon, which will take the burden away from the UNHCR as the sole entity conducting refugee interviews.

Belgium

After the invasion of Belgium in the First World War, somewhere between 225,000 and 265,000 refugees fled to Britain. They received substantial popular support, in part due to the reports (in part true, in part exaggerated for propaganda purposes) of atrocities by the invading German army. Fewer civilian refugees made it the UK in WWII (around 15000) and public opinion had shifted. Rather than ‘plucky little Belgium’, the country was now seen as having betrayed the Allies by surrendering. In 1960, as what had been the Belgian Congo gained its independence, around 80,000 Belgians were evacuated as tensions and violence escalated.

At present, Belgium, like other European countries, has seen an influx of refugees primarily from Syria. Whilst the numbers are much smaller than in many other parts of Europe, the response has been, in some quarters at least, hostile.

The mayor of a swanky beach resort near the port city of Zeebrugge called for a “camp like Guantanamo” to house them. And on February 1, Carl Decaluwé, governor of the Province West-Flanders, urged Belgians not to feed refugees “otherwise more will come.”

On the other hand:

Volunteer Ronny Blomme, who has been helping migrants by giving them food, drinks, sleeping bags and warm clothes at the church since they began arriving in November, says he is wants to make up for the failure of officials to deal with the problem humanely.

“Trying to scare these people is useless — they traveled 8,000 kilometers [4,970 miles] to get here and they have already lost everything,” he said. “What we need is a humanitarian solution.”