Archive for July, 2014

The beauty of the game

Posted by cathannabel in Football on July 12, 2014

I’ve written quite a bit about football over the couple of years that I’ve been blogging. But I’ve said next to nothing about what happens on the pitch. I’ve talked about what happened on the terraces one day in April 1989, and the quarter-century aftermath. I’ve talked about the various nations competing in the World Cup and their history and politics in terms of the displaced people across the globe. But the game itself?

I can talk about music, though I’m not a musician, I can talk about art though I’m no artist. But I can’t talk about football, the playing of the game, without it sounding second-hand, words and phrases borrowed from the pundits on the telly or the pundits in my own life.

Nonetheless it’s played an important part in my life, still does. I barely knew the game existed until the early 70s, when the family moved to Nottinghamshire, and my brothers determined that our loyalties would henceforth belong to Nottingham Forest. And I went along on a Saturday, wearing the scarf that I knitted myself (the only piece of knitting I ever finished, at one time embroidered with the names of the players) at least until the final whistle blew and we hid our scarves away and legged it to the bus station. I stood on the Trent End, being pushed one way and another, pressed up against the barriers till it hurt, sometimes. I went along to watch them train in between home games, to watch the reserves play, to get their autographs. I loved the atmosphere, until the violence – always simmering – seemed to come every week to the boil, and I was too afraid and too sick to love it any more.

Nonetheless it’s played an important part in my life, still does. I barely knew the game existed until the early 70s, when the family moved to Nottinghamshire, and my brothers determined that our loyalties would henceforth belong to Nottingham Forest. And I went along on a Saturday, wearing the scarf that I knitted myself (the only piece of knitting I ever finished, at one time embroidered with the names of the players) at least until the final whistle blew and we hid our scarves away and legged it to the bus station. I stood on the Trent End, being pushed one way and another, pressed up against the barriers till it hurt, sometimes. I went along to watch them train in between home games, to watch the reserves play, to get their autographs. I loved the atmosphere, until the violence – always simmering – seemed to come every week to the boil, and I was too afraid and too sick to love it any more.

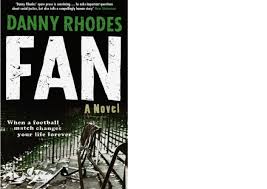

Reading Danny Rhodes’ Fan brought it all back. He writes about following Forest, and I recognise everything he describes. But at the same time my experience of being a football fan was so different – being a girl, a swotty, geeky girl at that, I could never have been part of the beery sweary scrappy bloke culture.

I never lived for it, but I loved it. Time was I knew all the names, the numbers, the fixtures, the results. Time was I could recognise every player on the cards my brothers collected (the Panini stickers of their day) – and I was tested on this regularly and rigorously. I lost that over the years, lost touch with the minutiae of the team and the game, but never stopped checking the results, and feeling a glimmer of excitement if we were doing well in a Cup or league, or – at least as often – frustration and gloom if we weren’t.

I never lived for it, but I loved it. Time was I knew all the names, the numbers, the fixtures, the results. Time was I could recognise every player on the cards my brothers collected (the Panini stickers of their day) – and I was tested on this regularly and rigorously. I lost that over the years, lost touch with the minutiae of the team and the game, but never stopped checking the results, and feeling a glimmer of excitement if we were doing well in a Cup or league, or – at least as often – frustration and gloom if we weren’t.

Looking back, I’d thought that ‘my’ Forest era was the glory years of Clough, European cups and league triumphs. But in fact, the years when I was going most Saturdays, when I was the most engaged and invested, were before that. In fact, I supported Forest under three managers before Clough & Taylor arrived (Gillies, Mackay and Brown), and saw them relegated in ’72 to the then 2nd division.

Clough came in ’75, the year I went up to University in Sheffield, and my match attendance plummeted. But I still went, when I could, and saw two League Cup finals (victory over Southampton, defeat to Wolves), and a European cup tie against Grasshoppers Zurich. And I saw the players who Clough inspired to greatness, many of whom I’d been watching in the reserves before Clough saw what they could be capable of and gave them the chance to achieve it. It’s been a pretty bumpy ride since then, and most seasons I apologise to my son for making him a Forest fan – I may have seen some dire, desperate games and some crushing defeats, but I also saw the team when they were the best.

So I can reminisce, but I can’t pontificate about the game. I know genius when I see it – old clips of Best, new clips of Messi, and my memories of seeing John Robertson, short stocky guy, invisible on the left wing until he suddenly took off and scored before the opposition had even registered his presence. Clough said ‘give him a ball and a yard of grass, and he was an artist’, but also that he was (or had initially appeared to be), an ‘unfit, uninterested waste of time’, perhaps the supreme example of Clough’s own genius.

But the offside rule is something I understand only fleetingly and I never spot an offside before it’s called. And I can’t analyse – I’m always kind of surprised and pleased when my general impressions of possession and dominance are confirmed by the ‘experts’ and the on-screen stats. Instead I get caught up with the ebb and flow, the swell of the crowd’s noise and the dying away when the moment is lost, the grace and athleticism, the exhilaration and despair. I can share in that, and I’ve wept over results before now, most recently when Ghana were knocked out of the last World Cup thanks to a certain Uruguayan’s blatant hand-ball.

But when the City Ground crowd invites me to join in and assert that I hate Derby, or Leicester, or anyone else, I can’t do it. I don’t recall racist chanting on the terraces at Forest – and I do recall leaflets on the seats at a reserve game vigorously opposing the National Front and their calls for Viv Anderson to go back where he came from (as Clough pointed out, that would be Clifton, about 15 mins drive from the City Ground) – but I know that black footballers in Britain were subjected to vile abuse, and that this still happens in many European countries. I know that there are aspects of the game that are profoundly ugly.

I saw that in the violence that became endemic in the game – people who turned up for the fight, not for the football, driving other spectators away, and creating the vicious circle of aggressive policing, media contempt and political rhetoric that led us inexorably to Hillsborough. I know that the tribal loyalties that make following a football team so emotional can be dangerous, and are dangerous when they’re linked to other loyalties – religious, ethnic, political. And there’s a dispiriting cynicism in the way the game is played (nothing new, whenever I see the perpetrator of a blatant foul turning to the ref with an expression of affronted innocence, I think of Leeds’ Allan ‘Sniffer’ Clarke).

Yet, despite all that, there’s something wonderful about it all. The experience of being at a match (Premier league, championship or Sunday junior league) is unlike anything else I do. If I’m at a gig, probably the closest thing, where one is caught up in the collective experience, responding emotionally and vocally to what’s happening on stage, still, I know that it’s not going to end with the band I’ve come to see being humiliated and defeated. Every football match presents that possibility.

And all of the above is why Hillsborough is seared into my soul. I wasn’t there. But I stood in my kitchen, just across the valley, watching Grandstand, trying to figure out what was happening. And later, watching as the death toll crept higher and higher. And then hearing the way the narrative twisted – so soon – into the familiar territory of blame. I wasn’t there but it haunted me, and still does. Because it sums up what British football had become – the adversarial policing, the pens that crushed the life out of so many, and the contempt for the fans that allowed the lies to be believed, in the face of all the evidence, for so long.

I do feel some nostalgia for the days when I stood on the Trent End. It is so much safer now, so much tamer. And I’m glad of that, even whilst I feel the loss of the visceral excitement that was part of the experience then. Because that’s forever associated with the reasons I stopped going to matches. And, overwhelmingly, with 96 football supporters who never got home after the match, and the families who’ve had to fight for 25 years for the truth of what happened .

Can we find a middle ground? Can football be family friendly, safe, without being bloodless and corporate? The contradictions will always be there, I think. And I will always have this ambivalent relationship with the beautiful game but will be – can’t help it, couldn’t change it if I wanted to – Forest till I die …

http://www.dannyrhodes.net/fan.html

Danny Rhodes, Fan, Arcadia Books, 2014