Archive for category Politics

The Light in the Darkness – Holocaust Memorial Day 2021

Posted by cathannabel in Genocide, Politics on January 27, 2021

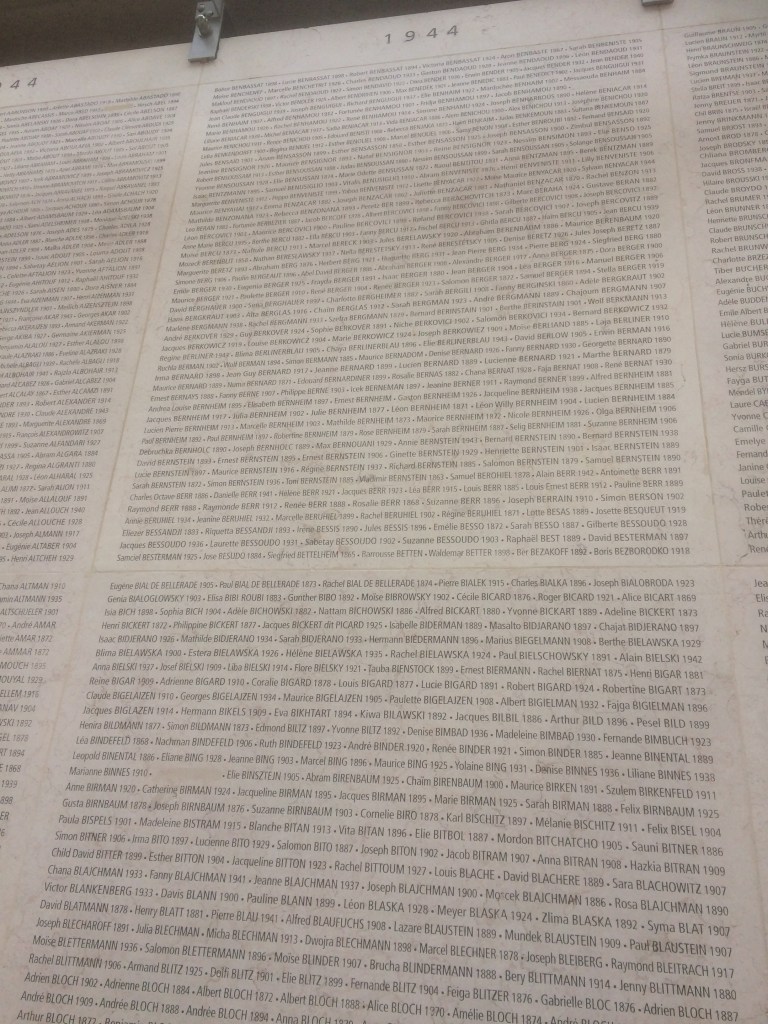

Be the light in the darkness is an affirmation and a call to action for everyone marking HMD. This theme asks us to consider different kinds of ‘darkness’, for example, identity-based persecution, misinformation, denial of justice; and different ways of ‘being the light’, for example, resistance, acts of solidarity, rescue and illuminating mistruths.

https://www.hmd.org.uk/what-is-holocaust-memorial-day/this-years-theme/

For there is always light. If only we’re brave enough to see it. If only we’re brave enough to be it.

Amanda Gorman, ‘The Hill We Climb’

The darkness that overwhelmed Europe’s Jews under Nazi persecution has engulfed so many since then, in Rwanda, in Bosnia, in Cambodia and Darfur. And today in China and in Myanmar, Uighur and Rohingya Muslims face the threat of genocide. We’ve been here before, again and again, and every time, when it’s over, we pledge that we will never again allow hatred to triumph. But at the point when the world could make that pledge real, could stop genocide in its tracks, then we hesitate, fatally. Now is that point, yet again, when we need to name what is happening, with all of the implications and responsibilities that carries, to shine a light on what is happening now, rather than afterwards.

And the darkness creeps back again too, when far right activists wear their Holocaust denial openly. We’ve seen the swastika flag flown in Charlottesville. The ‘Camp Auschwitz’ T shirt in the Capitol Building. The British Union of Fascists banner in Trafalgar Square. It’s not that we haven’t seen it in daylight before – it has never really gone away. But the murky corners of the internet have proved to be the ideal environment for conspiracy theories to grow, to be shared, to ensnare more and more people. People who start off as 9-11 truthers, anti-vaxxers, Covid-hoax activists, almost any conspiracy theory you care to mention, will find Holocaust denial thriving on the websites and forums. And it spills out, and where it isn’t opposed, it gains confidence and feels emboldened, legitimised, empowered. It is, as David Baddiel says, ‘the archetypal lie in our culture, from which all the other lies fan out’. It is so very hard to counter. Facts, evidence, personal testimony, all seem to bounce off without leaving any mark. But we have to speak the truth anyway, we have to offer the facts, the evidence, the personal testimony, the common sense to counter the fantasy, the rigour to expose the lies. We have to call it out whenever and wherever we encounter it. Baddiel’s superb documentary did just that, with passion and clarity.

I don’t have my own story to tell. So I will carry on reading and sharing both the scholarship and the personal testimonies, of those whose accounts shine light not only on what happened at those other times and in those other places but what is happening now.

My 2020/21 Reading List

- Susi Bechhofer – Rosa’s Child: One Woman’s Search for her Past

- Miriam Darvas – Farewell to Prague

- Saul Friedlander – Nazi Germany and the Jews: The Years of Extermination

- Anna Hajkova – The Last Ghetto: An Every History of Theresienstadt

- Heda Margolius Kovaly – Under a Cruel Star: A Life in Prague, 1941-1968

- Eva Noack-Mosse – Last Days of Theresienstadt

- Michael Rosen – The Missing: The True Story of My Family in World War II

#BlackLivesMatter #Wakanda Forever

Posted by cathannabel in Film, Literature, Politics, Racism on August 29, 2020

I’ve been trying to write this piece for weeks now. Hesitating because, after all, why would anyone need to read the thoughts of a white, middle-aged, middle-class English woman about something she has never experienced, and could never experience? But nonetheless this post has been buzzing around in my head for so long, and I know that the only way to stop that is to write.

And, this morning, I woke as so many did to the awful news that Chadwick Boseman, the actor best known as the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s Black Panther, has died at only 43 years old. I remembered how I felt in the cinema watching that film, how exhilarating it was to see the large screen filled with powerful, beautiful black people, in control of their destinies, white people largely irrelevant. And how I thought of what that must have felt like to people of colour, those who’ve seen movie after movie where they are absent, or peripheral, or victimised, or expendable. And those who have been waiting, whether they knew it or not, for a super hero who resembled them.

Some disclaimers. I’m not trying to prove anything here, not trying to get approval or validation. I’m talking, primarily, to other white people, about how we can learn and listen, how we can recognise and take account of our privilege, and know when to speak and when to STFU. If I get something wrong feel free to tell me (but I’m not asking you to educate me, that’s my responsibility). I’m a work in progress, still, at 63. I expect and hope that I’ll still be learning, expanding my understanding, for the rest of my life, whilst my faculties are intact at least.

So, where am I from? No, where am I really from? My upbringing was very different to that of anyone I went to school with in Chatham or Mansfield in the late 60s/early to mid 70s, very different to that of my cousins and other wider family. It shaped my response to the racial politics of the UK in that era and beyond. It influenced what I read, and what I watched.

When I was three years old, we (my parents, myself and my two younger siblings) flew to a new life in Ghana, West Africa. Of course we were massively privileged in our lives there, in the immediate aftermath of independence, living on the University campus in Kumasi, where my father taught Physics and Maths. We were ‘expats’, not immigrants. No one expected us to integrate, to assimilate, to adopt Ghanaian dress or diet, or to learn the language. My school teachers were all British, my classmates included Ghanaian children, but also British, American, Canadian. (When we moved to Northern Nigeria, there were no African children in my class. Not one.)

That upbringing did not give me a means to understand what it is to be black in Britain. My white skin gave me privilege as a member of an ethnic minority in West Africa as it does here where it makes me part of the norm. But those childhood experiences did broaden my horizons, expand my consciousness and my sympathies, and gave me a wealth of experiences against which to measure the attitudes and assumptions I encountered back home.

I think first of all, of the Door of No Return. Cape Coast and Elmina Castles, two of the forts on the Ghanaian coast which were the point of departure for the slaves, the last place they saw before they were crammed into the holds of the ships for the Atlantic crossing. I don’t recall in detail what my parents told me about their history when we visited, but I still recall the place, and the association with horror, the chill, even in the humid heat of Ghana.

I remember the first time I heard a white person say something casually racist. I remember not so much shock or offence, but bafflement. It seemed to me so incomprehensibly stupid, to generalise in that way. It made no sense to me then, that first time, in Africa, any more than it did later, in Chatham or Mansfield. I never knew how to respond – where do you begin, with something so incomprehensibly stupid?

My memories of Ghana are vivid, warm, happy. I know I can lay no claim to Ghana as part of my heritage – I lived there for just five – albeit formative – years. When I use my Ashanti day name, Abena (girl born on a Tuesday) as part of my Facebook name, when I use an image of kente cloth as the background to my Twitter profile, am I, as I hope and intend, honouring a part of my life for which I am immensely and profoundly grateful, or am I appropriating something to which I have no right? But those things (and my support for the Ghana national football team, and my love of West African music) feel like part of me.

Our parents taught us well. At an early age (before we came home to England, so before I was ten years old) I knew that whilst other ‘expats’ were planning, in light of the rapidly deteriorating situation in Nigeria, to move to jobs in Rhodesia or South Africa, my parents never would. And they taught me why. (Their passionate opposition to those regimes would probably have made them persona non grata anyway.)

I knew that Martin Luther King was an important man, a good man, who represented the values that my parents were teaching us, and they had taught me well enough that I knew by the time I was ten years old that his murder was a terrible thing, a huge loss to the world.

As a teenager, I was drawn to the American civil rights struggles, and I read everything I could get hold of. I read MLK, Angela Davis, George Jackson, James Baldwin, Malcolm X.

But one of the most powerful books for me was by a white man. John Howard Griffin, a white journalist, disguised his skin with a combination of medication (anti-vitiligo treatment), tanning and cosmetics, and went South. He was motivated by the recognition that the only way to know what it was like to be black in the USA, was to become black in the USA. Of course it wasn’t the same – he had an exit strategy (although he was subjected to threats and a near-fatal attack when the book was published and his identity revealed), and he had experienced most of his life up to the point of his self-transformation as a white man with all the privileges that entails. But his account is viscerally compelling. What stayed with me from my first reading was the ‘hate stare’ – something I would never experience, almost certainly never witness.

Alex Haley’s Roots (whether it is fiction or history, or a blending of the two) gave me a black epic, a story that spanned centuries and continents, that took up the story of the people who had been herded through the Door of No Return, and did not flinch from the brutality of slavery and of the injustice that persisted for so long after.

I almost never talked about my interest in the politics of race, not to my schoolfriends. I feared discovering that their response would make friendship problematic, or impossible. And, to be honest, as a teenager desperate to fit in, I feared being regarded as nerdy or odd. We talked about pop music, telly and boys, not about politics. And the strange culture of the times meant that one tribe listened to virtually no black music (though they allowed a free pass to Hendrix), whilst another listened to mainly African-American and Caribbean music, whilst being associated with prejudice against people of South Asian origin, and with the nascent National Front. It was dangerous territory, even though in my grammar school there was, throughout my years there, just one non-white girl (from India, as I recall), and in the Mansfield area at the time, the largest immigrant community was Polish. I kept reading though, just didn’t talk about it.

I read a number of the Heinemann African Writers series from my parents’ bookshelves (Chinua Achebe, Buchi Emecheta, Bessie Head, Ngugi wa Thiongo, Camara Laye, Wole Soyinka). I read Alan Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country, and Trevor Hudleston’s Naught for your Comfort. I read E R Braithwaite’s Please Sir (a whole heck of a lot less soppy than the film) and Paid Servant.

And those books, and world events, led me on to Steve Biko and Nelson Mandela, to Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison, to Kwame Anthony Appiah, David Dabydeen and more recently to Reni Eddo Lodge and David Olusoga.

Meantime, the sound of Ghana, the highlife music that had wafted over from the student residences to our home on campus, was part of me. I was prepped to respond to black American music, to Motown and Stax and Philly, and to ska and reggae. And then I heard Osibisa, and that started a journey of exploration of African music – music from all over that continent, but finding the sounds of Mali and Senegal took hold of me in a way that no other music did. I still feel that way.

For all this, I realised part way through this year, as I nerdily compiled my list of what I’d read, that it was disappointingly, dispiritingly, shamefully white. Somehow I’d kept on gravitating (during what, to be fair, has been a brutal year, full of loss and sadness) towards familiar voices, familiar histories, familiar settings. That this realisation coincided with the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd is no coincidence at all.

However well I have been taught, however widely I have read and listened, my life can still be told (if one skips those few years in ‘darkest Africa’, as my grandfather always referred to it) without reference to my race. My journey through school and work, marriage and parenthood, has been untroubled by the colour of my skin. I have experienced prejudice, sure, as a woman in the workplace, and as a girl and woman in public spaces. I can extrapolate from those experiences, but it’s not enough, nowhere near.

So I need to read black writers, to hear those voices, those experiences and to let them expand my ideas, my sympathies, my knowledge. It’s powerful, and sometimes uncomfortable. But it’s a process that started when I was 5 or 6 years old, looking out of the Door of No Return.

Black lives matter. Of course they do. As the wonderful Dolly Parton put it, “…of course Black lives matter. Do we think our little white asses are the only ones that matter? No.” My words will make no real difference, I have few illusions on that front. But perhaps I will prompt someone to read more widely, to read more stuff by people who don’t look like they do, to risk being made uncomfortable, being challenged to rethink their assumptions, their bias, the language they use. Perhaps.

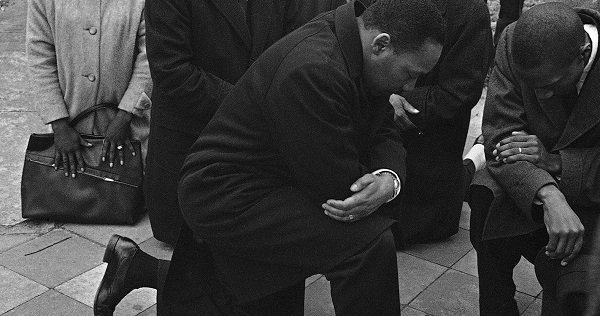

And would I take the knee? It’s a beautiful gesture, one of honour and respect. I wasn’t sure at first why it moved me so much, till I saw the photos of MLK and remembered. Yes, I’d take the knee, in a heartbeat. It might take a bit longer for me to get up again though…

My 2020 Reading List (so far):

- Chimamanda Adichie – Dear Ijeowole

- Arvind Adiga – The White Tiger

- Jeffrey Boakye – Black: Listed

- NoViolet Bulawayo – We Need New Names

- Angela Davis – Women, Race and Class

- Nicole Dennis Benn – Patsy

- Jason Diakite – A Drop of Midnight

- Bernardine Evaristo – Girl, Woman, Other

- Yaa Gyasi – Homegoing

- Mohsin Hamid – Exit West

- Afua Hirsch – Brit(ish)

- Meena Kandasamy – When I Hit You

- Andrea Levy – The Long Song

- Attica Locke – Pleasantville

- Kenan Malik – From Fatwa to Jihad

- Yvonne Adhimabo Owuor – Dust

- Laksmi Pamuntjiak – The Birdwoman’s Palate

- Johnny Pitts – Afropean

- Sunjeev Sahota – The Year of the Runaways

- Kamila Shamsie – Home Fire

- Margot Lee Shetterley – Hidden Figures

- Nikesh Shukla (ed.) – The Good Immigrant

- Ron Stallworth – Black Klansman

- Colson Whitehead – The Nickel Boys

Why we clap

Posted by cathannabel in Politics on April 30, 2020

Tonight, as we have done every Thursday night since this crisis began, we will open the bedroom window wide at 8.00 pm and lean out, clapping, and rattling a tambourine. Our neighbours come to their windows, or to the tops of their drives, some banging pots and pans or ringing bells. From the other side of the house we can hear the same sounds from across the valley. As we clap, we wave to each other, we remind ourselves and each other that we’re a community, that we need each other.

And every Friday morning I see grumpy posts on Twitter, pointing out that if we vote or ever have voted Tory, we’ve no business clapping for carers. Pointing out that those carers need PPE and testing and decent salaries more than they need our applause. Really? We had no idea! We thought that clapping would solve everything!

Of course I can see where this cynicism comes from. I’m not an automatic joiner-in. When I see Tory politicians who not so long back brayed their delight at having blocked a payrise for nurses, and who support an immigration policy that defines most of our carers as low-skilled workers who would not be eligible to come here under the points-based system, joining in the applause, I share that cynicism.

When I hear that we are enjoined to clap for Boris, or sing to congratulate him on the birth of his umpteenth child, I’m having no truck with that. Nor even to sing birthday greetings to the redoubtable Captain Tom. I am cross when the BBC News claims that the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge ‘led’ the applause. Not my applause, they didn’t. I can be as grumpy as the next person, in other words.

This whole thing wasn’t started by politicians or royals. It was an idea mooted on social media, inspired by the video clips we were all seeing from Italy and elsewhere, of spontaneous rounds of applause for health workers, and displays of solidarity within communities. I wasn’t sure it would take off here – we are British, after all – but it has, and I’m glad.

Because if we want, not to go back to how things were, but to learn from this crisis, to learn who we really need, and how we can support those most valuable members of society, not just in times of crisis but at all times, we need to keep making a noise.

We’re making a noise about all of those people who are risking their lives, who are keeping us safe, who are taking care of us, because we want to ensure that when the crisis is past they don’t just disappear back into the shadows. We’re making a noise about carers because we want to ensure that when the crisis is past, their value is not forgotten.

I don’t even really care whether those who clap now have voted Tory in the past. I care that their values may be shifting, may have shifted, and that even Tories may think twice about disparaging or dismissing those who are our heroes now. I don’t care if they haven’t been angry in the past, as long as they understand a bit more of the anger now, as we see the impact of underfunding of the health service, inadequate staffing levels and failures of planning.

I care that now, as so many of our priorities and values have been overturned, we are sharing both the gratitude and the sense that those priorities and values were wrong before, and must change permanently.

Polly Toynbee’s response to the clap refuseniks chimes with my own:

So when next week’s clap for the NHS comes, join in out of gratitude but also out of anger – anger at how depleted the nursing workforce has become and how badly the successive Conservative governments have treated the profession.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/24/year-nurse-tories-10-years-bad-care-nhs-crisis

I’m reminded too of how, when there have been major terrorist attacks, many attempts to assert solidarity with victims, to emphasise our shared humanity in the face of hatred have been derided as clichéd and simplistic.

As Stig Abell says:

At moments of crisis and trauma, the use of comprehensible and familiar phrasing is itself a sign of something important: it is a bid for connection. Cliché demonstrates community, our intention to understand one another. It does not matter that “standing in solidarity” has no practical import, or that prayers may be just so much shouting into a void. … Clichés are good things when pressed into the service of communication in the aftermath of the incomprehensible and the traumatic. They often reveal the good intentions we share, and they are more valuable than ever.

https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/cliche-terror-attacks/

Kenan Malik makes some powerful points too, about the use of the word ‘hero’. If that normalises the deaths of NHS staff and other carers in some way, suggests that, like soldiers in wartime, they signed up to put their lives in danger, it’s dangerous. They didn’t. Pharmacists and health-care assistants and midwives and GPs, paramedics, nurses and consultants, signed up to help people, to save lives (directly or indirectly), but there was no reason they would have thought the job could kill them. Of course that makes it all the more remarkable that they’re doing what they’re doing, with or without the necessary level of PPE. When we applaud them we recognise that they weren’t given a choice (or only the choice between risking their life and walking away from patients in need of help).

Few of them would want to be described as heroes. Most would see themselves as ordinary people doing ordinary jobs in extraordinary circumstances. Many might suggest that most people in their place would do what they are doing. And they may be right in that. What they show is that heroism is a very human attribute. It is expressed not in having an incomparable character or possessing superhuman abilities but in being human to the utmost. Heroism in everyday life is, from this perspective, an expression of our humanness. It has become fashionable to denigrate humans as selfish or callous or egotistical. Many are. But many more are dedicated and compassionate and kind. Humans are far better than we often give ourselves credit for. In celebrating the endeavours of nurses and care workers and bus drivers and cleaners and volunteers, and the myriad others working to pull us through these surreal times, we should not forget that many are forced to be heroic, through a lack of resources or poor conditions.

https://kenanmalik.com/2020/04/26/heroism-and-the-quality-of-being-human/

And, as Rachel Clarke@doctor_oxford, said on Twitter,

We’re not soldiers. We didn’t sign up to die for a cause. We don’t want red arrows, medals, jingoism or war rhetoric. We want masks, gloves, gowns & visors. Could you actually focus your minds on that, please?

We can agree, passionately, with that. But the Thursday night clapping is not an expensive PR stunt. It’s ordinary people – people who don’t have the resources or the clout to get carers what they need, to change government priorities or policies. We’re telling the carers – and it’s a broad definition, not just the ones who save lives in the ICU – that they are cared about, and the government that we care about them, and that we expect our government to translate that into the action that’s needed to keep them safe, so they can keep us safe.

We clap for all of these people (and those whose deaths have not yet been recorded). And we clap for our family, friends, neighbours and colleagues on the front line. We can’t stop now. And when this crisis is no longer a crisis, we mustn’t stop making a noise.

J’accuse…

Posted by cathannabel in French 20th century history, Politics on February 23, 2020

The basics of the Dreyfus affair are, I had thought, fairly well known.

Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery officer in the French army, was accused of treason in 1894 and convicted. He was stripped of his army uniform and badges in a ‘ceremony of degradation’, all the while declaring his loyalty to France and his innocence. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and deported to the Devil’s Island penal colony in French Guiana.

As members of his family and some others argued tirelessly for his innocence, Lieutenant Colonel Georges Picquart, the newly appointed head of the Military Intelligence Service, discovered that the key piece of evidence against Dreyfus was in the handwriting of another officer, Esterhazy.

Despite this, and the lack of other evidence of Dreyfus’s guilt, Picquart and the other ‘Dreyfusards’ faced the implacable hostility of the establishment to any suggestion that the case should be reviewed. That they succeeded in the end is a tribute to their resilience in the face of threats to their careers and indeed to their lives. That it had to be such a hard fight reveals the extent and virulence of French anti-semitism at that era.

Dreyfus was framed. Because he was a Jew, people were ready to believe that he would not be loyal to France. And because he was a Jew, and the true culprit was not, it was unthinkable that he should be vindicated and a non-Jew convicted in his place, whatever the truth. Picquart realised not only that Dreyfus was innocent, but that the establishment knew this, and had no intention of doing anything about it, but would allow him to continue to suffer on Devil’s Island, whilst the real guilty party (also known to the powers that be) retained his freedom, his army post, his salary.

Dreyfus was pardoned (not found innocent) in 1899. In 1906 he was reinstated in the army, but retired a year later, his health having suffered greatly from the privations of Devil’s Island. His most famous champion, Emile Zola, had died in 1902, in suspicious circumstances. Dreyfus himself died in 1936, and members of his family fled to the Unoccupied Zone from Paris when the Occupation began. His granddaughter, Madeleine Levy, was a member of the Resistance, who was arrested in 1943 and murdered in Auschwitz.

The case played its part in the founding of Zionism as a political force. As Theodor Herzl said:

If France – bastion of emancipation, progress and universal socialism – [can] get caught up in a maelstrom of antisemitism and let the Parisian crowd chant ‘Kill the Jews!’ Where can they be safe once again – if not in their own country? Assimilation does not solve the problem because the Gentile world will not allow it as the Dreyfus affair has so clearly demonstrated.

The ‘affair’ divided France. One was either pro- or anti-Dreyfus. The anti-camp used every anti-semitic trope and image in the repertoire to vilify Dreyfus and his supporters. And this rhetoric never went away. The ground was well-prepared for the Vichy regime’s collaboration with the Nazi occupiers from 1940. (Charles Maurras of far-right anti-semitic movement Action Francaise called his conviction in 1945 for acts of collaboration ‘the revenge of Dreyfus’.)

See any similarities with the case of Julian Assange? Me neither.

But John McDonnell would disagree.

I think it is the Dreyfus case of our age, the way in which a person is being persecuted for political reasons for simply exposing the truth of what went on in relation to recent wars.”

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2020/feb/20/julian-assange-case-is-the-dreyfus-of-our-age-says-john-mcdonnell

Where do we start with this nonsense? Dreyfus was not persecuted for political reasons. He was an army officer, just doing his job, notable only for being Jewish. He was framed because he was a Jew. He was persecuted solely because he was a Jew.

Even if one believes that the prosecution of Assange is unjust, he wasn’t picked out because of his race to be used as a scapegoat for someone else’s crime.

Even if Assange is a victim of a miscarriage of justice, and that is very much open to argument, one cannot (surely?) speak of the Dreyfus affair without speaking about anti-semitism.

Anti-semitism fitted him up. Anti-semitism condemned him to life imprisonment. Anti-semitism blocked any review of his case and threatened those who supported him. Anti-semitism vilified him and all Jews in the crudest of terms. Without anti-semitism, there is no Dreyfus affair.

McDonnell’s comparison drew swift condemnation, but his response suggests he doesn’t really get why it was so offensive:

Just like the Dreyfus case, the legal action against Julian Assange is a major political trial in which the establishment is out to victimise an innocent. On that basis, of course it’s right to assert that it’s a parallel.

https://politicshome.com/news/uk/political-parties/labour-party/john-mcdonnell/news/110034/john-mcdonnell-defends-comparison

Over the last few years, I have raged and despaired on so many occasions as Labour politicians, councillors and activists have demonstrated their inability to recognise and comprehend anti-semitism. This issue has divided and still divides the Party. Given how damaging this has been, how is it possible that McDonnell did not see what was wrong with his appropriation of this key moment in the twentieth-century’s shameful history of anti-semitism? As Ian Dunt puts it, ‘to say it is a misreading of history is to put it in its kindest possible light’.

It’s a form of erasure. And that’s not just wrong, it’s dangerous.

Here’s hoping… New Year 2019/2020

Posted by cathannabel in Events, Personal, Politics on December 31, 2019

It’s just another New Year’s Eve. Nothing actually changes on New Year’s Day, we know that … but that never stops us hoping that some things will change, making plans and resolutions, wishing and wondering.

For many of us, looking back at the year just ending cannot be wholeheartedly celebratory. Of course, there have been good things – friends and family, love and laughter, things that brought us pleasure and achievements of which we are proud. We will recall those tonight, and be glad for every one of those moments and those memories. At the same time, if grief and loss has been part of our year we will acknowledge our sadness, and raise a glass to the people who we lost in 2019.

For many of us, looking forward to the year just about to begin cannot be simply hopeful, knowing that some of what we fear will happen. Some of us will be learning to live with loss, others will be anticipating loss. Many hearts will be heavy.

How do we face that countdown, knowing what we know? With tears, probably. With warmth and solidarity and love, wherever possible. With people to hold on to, literally or metaphorically, to accept our sadness and our fear, and to remind us of the good things that there were in 2019, and that will still be there in 2020.

When it comes to the state of the nation and of the world, it would be terribly easy to give up. I’ve noticed how often these days I choose not to watch the news or read the headlines which, for a politics junkie as I have been all my life, raised on family discussions around the tea table of the events of the day, is a big change. I can’t let that inertia continue.

I need to hang on to hope, and faith in humanity. There are reasons to be, if not cheerful, at least very cautiously hopeful, reasons to nurture those glimmers of hope. In the wake of attacks on mosques or synagogues, communities have come together to assert solidarity in the face of murderous bigotry. So many young people are fighting the good fight on the climate emergency.

Hope lies in recognising that the biggest problems we face are problems we can only deal with across borders and oceans, not by retreating behind our walls. Hope lies in people choosing to identify with and stand with people who aren’t like them, giving a damn whether or not it’s not their turn.

Meantime, in the face of lies we have to keep speaking and showing truth. In the face of hate we have to keep speaking and showing love. In the face of the horrors that seem to happen daily, far away from us or close to home, we have to keep speaking and showing faith.

Keep on keeping on.

Sometimes things don’t go, after all,

from bad to worse. Some years, muscadel

faces down frost; green thrives; the crops don’t fail,

sometimes a man aims high, and all goes well.A people sometimes will step back from war;

elect an honest man, decide they care

enough, that they can’t leave some stranger poor.

Some men become what they were born for.Sometimes our best efforts do not go

amiss, sometimes we do as we meant to.

The sun will sometimes melt a field of sorrow

that seemed hard frozen: may it happen for you.(Sheenagh Pugh – Sometimes)

Hang on to your hat. Hang on to your hope. And wind the clock, for tomorrow is another day

Theirs is a land with a wall around it

And mine is a faith in my fellow man…Sweet moderation, heart of this nation

Desert us not, we are between the wars(Billy Bragg, Between the Wars)

We are building up a new world.

Do not sit idly by.

Do not remain neutral.

Do not rely on this broadcast alone.

We are only as strong as our signal.

There is a war going on for your mind.

If you are thinking, you are winning.(Flobots – We are Winning)

The simplest and most important thing of all: the world is difficult, and we are all breakable. So just be kind.

(Caitlin Moran – How to Build a Girl)

If there’s no great glorious end to all this, if … nothing we do matters … then all that matters is what we do. ‘Cause that’s all there is. What we do. Now. Today. … All I want to do is help. I want to help because I don’t think people should suffer as they do, because if there’s no bigger meaning, then the smallest act of kindness is the greatest thing in the world.

(Joss Whedon – Angel)

Never be cruel, never be cowardly, and never, ever eat pears! Remember, hate is always foolish. and love is always wise. Always try to be nice, but never fail to be kind. … Laugh hard, run fast, be kind.

(The 12th Doctor, Twice Upon a Time)

Love is wise, hatred is foolish. In this world, which is getting more and more closely interconnected, we have to learn to tolerate each other. We have to learn to put up with the fact that some people say things that we don’t like. We can only live together in that way, and if we are to live together and not die together we must learn a kind of charity and a kind of tolerance which is absolutely vital to the continuation of human life on this planet.

(Bertrand Russell, Face to Face interview, 1959)

Five years

Posted by cathannabel in Brexit, Politics on December 27, 2019

Way, way back, in 2015, I wrote a piece responding to the outcome of a general election, with the same title. Things seem to be immeasurably worse today than they were then. (If you’d told me then about Brexit, Trump and a Labour Party poisoned by anti-semitism I would simply not have believed you.) But somehow we have to pick ourselves up, dust ourselves down, and start all over again. We have to decide what’s important now.

We go into 2020 with a Prime Minister who is devoid of integrity and principle, an Opposition that is (perhaps irrevocably) divided and even weaker than its numbers would suggest, and the certainty that we will be leaving the EU, quite possibly without a deal. It’s hard to find hope in that.

I can hope (though my hopes have been not just dashed but stomped on and the crushed fragments stomped on some more and then set fire to so many times since 2016 that I hardly dare) for a Democrat victory in the US elections. I don’t even know what to hope for, for the UK.

One day, somehow, we may be back in Europe (but let’s not start thinking about that now). One day, somehow, we may have an Opposition that will be willing to sacrifice ideological purity in order to gain power, so that they can actually do something about the things they claim to care about, other than shouting (usually at the wrong people) from the sidelines. Perhaps.

If we’re concerned about the impact of a rampant Tory government and a potential hard Brexit, not necessarily on ourselves but on others, what are we going to do about that? If we now feel politically homeless, how are we going to engage with politics over the things that really matter? If we despair at the mendacity, the bigotry, the contempt shown by too many politicians for the electorate or sections of it, and the overt bigotry faced on our streets by those whose accent, skin colour, or dress proclaim them to be different, how do we stand up for each other? I can’t answer my own questions, not yet.

My friend Mike Press doesn’t claim to have the answers either, but he’s asking the same questions. He posted this on Facebook, but it deserves a wider readership. It gives me a little, just a little, glimmer of hope. With enough thoughtful people, with enough kind people, with enough people who give a damn whether or not it’s their turn, maybe we can do this.

In the twelve years that I lived in Stoke-on-Trent there was a recurrent joke that did the rounds at election time – there’s no point in voting in Stoke, so the joke ran, they may as well keep all the Labour votes in the cellar of the town hall and take them out to weigh them every few years, such was the certainty that being a Potteries Labour MP was a job for life.

Clay runs in the veins of all Stokies, so it was suggested, on account of their passion for their craft, industry and identification with it. If it did then that clay was the same deep crimson as their politics. Nowhere else in Britain had swept Labour to power so decisively and swiftly as Stoke in the elections of 1918 and 1922. In the 1997 election – my last while living there – Labour was returned with 66% of the vote. We believed we were about to build the New Jerusalem. Since early on Friday morning all of The Potteries’ constituencies have become safe Tory seats.

I have voted in twelve general elections and in none of them has the defeat been as disastrous as this one. We have to go back to 1935 – the age of mass unemployment and Nazi Germany – for an election as catastrophic for Labour as the one we’ve just experienced. Our reactions to this have been perhaps understandable. After venting our anger on Boris Johnson and the Tory Party, we turn our barrels on the electorate itself. I’ve read comments from people here on Facebook and on twitter that described the English as “swinging to the far right”, that people who vote Tory are “stomach churning” or “just plain thick”. I’ve read comments that wish increased child poverty on Tory supporters “because they’ve just voted for it”.

The people of Stoke (and Blyth, Darlington, Redcar, etc, etc) have not swung to the far right, they are far from thick and they – along with all other folk – should never have child poverty wished upon them. There is serious thinking to be done to understand why people voted (or did not vote) in the way they did, and what is needed to build a new politics of hope. Because as progressives, we never lose hope. Out of every disaster comes hope. After Labour’s calamity of 1935, the party needed to rebuild, so it elected a little known new leader – Clement Attlee.

But a politics of hope requires empathy and kindness – despite the shock, anger and grief many of us currently feel. It also requires that we look very carefully at the data.

The English have not swung to the far right. The increase in the Conservative vote in England was 1.2% – a small increase on their lacklustre 2017 election performance. While many former Labour voters did vote Tory, more of them simply stayed at home. The demographics of age and education (and identity) are clearly reshaping political allegiances and replacing the old certainties of class. An interesting (and hopeful) phenomenon is a significantly reduced tribalism in politics. According to the Ashcroft poll, around one third of voters for all parties are now ‘tribal’ – the rest make up their minds as the campaign develops.

People vote for a whole variety of reasons. Along with 25% of SNP and 43% of Lib Dem voters, I voted for a party that is not my first choice, but I did so for tactical reasons. People voted Tory for three main reasons (according to the data): Brexit, the economy and leadership. None of the Tories I know support the party because they wish child poverty on others. A vote for Brexit and Scottish independence? Well the data also shows that 53% of UK voters supported pro-remain parties, and 54% of Scottish voters backed unionist parties. Those figures in themselves don’t tell us very much, apart from the need for a root and branch overhaul of our parliamentary democracy.

But looking at the data remains challenging given the distortions of the stultifying and dangerous bubbles we have created for ourselves. Social media has served to provide us with instant validation for our biases, assumptions and prejudices. As a consequence we do not engage with views we don’t agree with. We do not debate, we do not argue, we assert and feel validated by the ‘likes’ our assertions attract. We don’t need to empathise because we keep within our bubble of largely like minded people.

A few weeks ago my friend Adam StJohn Lawrence sent me a video he filmed on the streets of Hong Kong minutes after a riot. He was there to run workshops with government workers and citizens – not on the conflict, but on other issues. He recalled one of the people he was working with who gave their explanation of the crisis. They’re stuck – he suggested – they’ve run out of vocabulary, and this is the consequence.

It’s the same here. We’re stuck. There are no words that can bring us together – we’ve run out of them. We are in a state of continual conflict. How the Scottish question will be resolved by two governments that cannot find common ground, is very uncertain. Unlike European models of modern democracy that require negotiation and compromise, the British system is built on conflict, on “opposition”.

Now, let’s suggest an alternative – based on empathy and kindness.

There are two reasons that this is possible. First, because since Friday the majority of Labour and Lib Dem MPs are women, and that will necessarily bring in new values and behaviours both to those parties and to political discourse. Second, because Scotland has already placed kindness at the centre of its National Performance Framework. As Leslie Evans, Permanent Secretary to the Scottish Government, has said (not of this election, but in terms of public policy): “We need to recognise that the challenge ahead is not primarily a technical ask but a behavioural challenge and a reflection of the relationships we nurture. And if we can succeed in making this shift to instil kindness within public policy, we will succeed in improving lives.”

Politics is not an indulgence to prove a point. It’s no gladiatorial combat to entertain TV viewers. It’s not a game: “You can’t play politics with people’s jobs and with people’s services or with their homes.” Politics is “a behavioural challenge and a reflection of the relationships we nurture” and we either behave with kindness and respect, despite our differences, and at times actually relishing those differences, or we descend into a form of barbarism.

The UK and Scotland may well be on different paths to different futures. The task of all of us is to find a way into our respective futures based on empathy and kindness – understanding and respecting each other. With that foundation then we can empower citizens to make their own futures – to be active participants in democracy and in the public domain.

Despite all I’ve written about kindness, I still feel angry, still raw. I’m angry with Corbyn and the infantile disorder of the left who gave some folk no choice but to vote Tory. Above all, I’m angry with Johnson, Gove and the others for their lies, for their disrespect, for their self-serving and misplaced sense of entitlement.

But the folk of Stoke I feel no anger towards at all. They lost the steel works, then the mines, just before most of the potteries closed and as a consequence their sense of identity has been bulldozed. How do you think it feels to vote for one party for your whole life, and then switch to its arch political enemy? How do you think it feels to spend over a year on strike in a forlorn attempt to keep your mine open then decades later to use that stubby pencil to put a cross against Conservative in an election?

I don’t know either. All I know is that empathy and kindness might take us beyond this. And I know that getting angry with people just trying to get through life and make the best choices they can isn’t really on. We can and should be angry with those who lie and mislead. But for the rest, let’s just try to listen and understand.

Well, over there, there’s friends of mine

What can I say? I’ve known ’em for a long long time

And, yeah, they might overstep the line

But you just cannot get angry in the same way

No, not in the same way

Said, not in the same way

Oh no, oh no noArctic Monkeys

‘I never thought I’d need / So many people’

David Bowie, ‘Five Years’

My Life in Books – what I read in 2019

Posted by cathannabel in History, Literature, Politics on December 2, 2019

As you might expect, quite a lot of these titles crop up in my lists of the century and the decade (watch this space), but I’ve read things that fall well outside of those time frames, and things that I very much enjoyed but which didn’t quite make the cut. I haven’t included absolutely everything I read. One or two things were just a bit rubbish, and I’m going to ignore them. What that means is that everything here I enjoyed and/or was glad I had read (not necessarily the same thing), with the occasional caveat, and there are things that I enjoyed a very great deal. I’m not attempting to do a full review for all titles, or I’ll be here till 2021, just a few notes and links here and there, particularly for those titles which I haven’t written about elsewhere or which aren’t going to feature in all of the other (less fun) Books of the Year guides that are beginning to appear. The books that were published in 2019 are in bold, and my favourites have a little star by them, just so’s you know.

Crime, Thrillers, that sort of thing

Ben Aaronovich – The Furthest Station (part of the Rivers of London series, which I love. Moon over Soho is on my Century list)

Megan Abbott – Give me your Hand (a new author to me this year but one who I will follow up.)

Eric Ambler – Journey into Fear (classic thriller from 1940)

Kate Atkinson – Big Sky (new Jackson Brodie!)*

Mark Billingham – Love Like Blood, As Good as Dead, The Bones Beneath, Die of Shame, The Killing Habit (the excellent Tom Thorne series)

Stephen Booth – Fall Down Dead (Cooper & Fry series, set in the Peak District – I’ve read quite a few of these, but not in chronological order, and I keep feeling there’s back story that I’m missing! Will have to fill in the gaps.)

Sam Bourne/aka Jonathan Freedland – To Kill the Truth (follow up to To Kill the President, which was a startlingly close to reality account of Trump’s presidency as well as a nail-biting thriller. This one’s preoccupation is clear from the title – the events described may not be entirely plausible but the basic premiss chills, nonetheless, and Bourne/Freedland knows how to keep his audience gripped.)

James Lee Burke – New Iberia Blues, Robicheaux* (Dave Robicheaux series. Robicheaux is on my Century list)

Jane Casey – Love Lies Bleeding, One in Custody (two Maeve Kerrigan novellas), Cruel Acts* (new Maeve Kerrigan! on my Century list), How to Fall (first in Casey’s YA Jess Tennant series)

Harlan Coben – Tell No One, The Woods

Eva Dolan – Tell no Tales (second in the Zigic & Ferrera series, set in a Hate Crimes Unit)

Louise Doughty – Dance with Me, Honey Dew, Crazy Paving

Tana French – In the Woods, The Likeness, Faithful Place, Broken Harbour* (the first four in the Dublin Murders series – Broken Harbour is on my Century list), The Wych Elm*

Frances Fyfield – Half-Light (I read several of her crime novels back in the ‘80s and ‘90s but nothing more recently. This one is from ’92 and published under her real name, Frances Hegarty, but has reminded me to read anything by her that I’d missed).

Robert Galbraith – Lethal White (the latest Cormoran Strike – The Cuckoo’s Calling is on my Century list)*

Isabelle Grey – Good Girls Don’t Die (another new writer to me this year, and another who I will follow up)

Elly Griffiths – Zig Zag Girl, The Blood Card, Smoke and Mirrors, The Vanishing Box* (the first four in the Brighton Mysteries series, which I love), The Stone Circle* (the latest Ruth Galloway – on my Century list), The Stranger Diaries (first in an intriguing new series)

Jane Harper – Force of Nature, The Lost Man* (the latter is on my Century list)

Sarah Hilary – Never be Broken* (new Marnie Rome! on my Century list)

Susan Hill – Hero, The Comforts of Home* (a novella and the latest in the Simon Serrailler series, on my Decade list)

Doug Johnstone – The Jump, Gone Again

Philip Kerr – The Lady from Zagreb, The One from the Other, Prussian Blue*, Greeks Bearing Gifts (Bernie Gunther series. Sadly Kerr died last year, and so whilst there are a couple of Bernie Gunther novels that I haven’t yet read, that will be that. I’ll miss him. Prague Fatale is on my Decade list.)

John le Carré – Our Game, Absolute Friends (The Constant Gardener is on my Century list, and his memoir Pigeon Tunnel on the Decade list)

Laura Lipmann – Sunburn (on my Century list)*

Attica Locke – Black Water Rising (on my Century list)*

Mary McCluskey – Intrusion

Val McDermid – A Darker Domain (Karen Pirie series – I have read a couple of these now and much prefer them to the Wire in the Blood series, which I just can’t get along with. That puzzled me, given my love for the genre and McDermid’s place in the crime-writing pantheon, so I’m glad to have found these and will follow the series up )

Thomas Mullen – The Lightning Men (sequel to Darktown, which is on my Century list)*

Louise Penny – Still Life (first in the Inspector Garnache series – another series to follow up)*

Ian Rankin – In a House of Lies* (on my Decade list), Rather be the Devil, Hide and Seek, Naming the Dead* (on my Century list) (all Rebus novels)

Cath Staincliffe – Desperate Measures (a Blue Murder novel. Staincliffe’s stand-alone novels The Silence between Breaths and The Girl in the Green Dress are on my Century and Decade lists respectively, and I have thoroughly enjoyed her Sal Kilkenny series too)

Lesley Thomson – Ghost Girl (follow up to The Detective’s Daughter)*

Sarah Vaughan – Anatomy of a Scandal (political/psychological thriller, disturbing and compelling)

Sci-fi/Horror/Dystopian Futures etc

Margaret Atwood – The Testaments (sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, on my Decade list)*

Ted Chiang – Stories of Your Life and Others (includes the short story that inspired the film Arrival, on my Century list)*

Andrew Michael Hurley – Devil’s Day* (his second novel – his debut The Loney was on my Century list)

Stephen King – Elevation, Gwendy’s Button Box, The Institute* (two fairly slight novellas and a stonking new one, which is on my Decade list)

Audrey Nifenegger – Her Fearful Symmetry*(there’s a sequel to her more famous Time Traveller’s Wife in the works, I believe, but this one is also excellent, spooky and moving)

Claire North – 84k* (a gripping and disturbing dystopia, in a society where everything is commodified and human rights have been abolished)

Iain Pears – Arcadia

Philip Pullman – La Belle Sauvage (on my Decade list), The Secret Commonwealth (the first two in his new trilogy)*

Historical Fiction

Marjorie Bowen – Dickon (a 1929 novel about Richard III, from a hugely prolific but largely forgotten author. The Viper of Milan thrilled me to bits as a young teenager)

Sarah Dunant – Sacred Hearts (third in her Renaissance trilogy. It’s set in a convent, and by chance I read it immediately after The Testaments, which set off all sorts of interesting echoes)*

Robert Harris – Imperium, Lustrum, Dictator (the Cicero trilogy, read in preparation for and during a visit to Rome)

Sarah Moss – Bodies of Light (on my Century list)*, Signs for Lost Children, Night Waking*

Elizabeth Strout – Abide with Me

Amor Towles – A Gentleman in Moscow

Sarah Waters – The Paying Guests

Kate Atkinson – Transcription* (WWII/Cold War set novel, about secrets, lies, paranoia, invention. The Guardian described it as ‘an unapologetic novel of ideas, which is also wise, funny and paced like a spy thriller’.)

Other Fiction

André Aciman – Call me by Your Name

Peter Ackroyd – The Great Fire of London

James Baldwin – Giovanni’s Room* (Baldwin’s 1956 novel is a groundbreaking account of bisexuality, with a non-linear timeline. It’s a powerful read – I read quite a lot of Baldwin as a teenager, including the later Another Country, where the themes of race and sexuality are intertwined, as well as his novels exploring the black experience in the US)

Arnold Bennett – Clayhanger (published 1910, first in a trilogy – or possibly a quartet – set in Bennett’s ‘five towns’ in the Potteries, with a very striking female character in Hilda Lessways)

Jonathan Coe – Middle England* (on my Decade list, the follow up to The Rotter’s Club and The Closed Circle)

J M Coetzee – Disgrace (this has been on my bookshelf for many years and for some reason I only got round to it this year. It was excellent, but I don’t know that I want to read more by him, however good and important he is)

Michel Faber – The 199 Steps (read following a short break in Whitby)

Sebastian Faulks – Paris Echo (this should have been right up my street, and I did enjoy a great deal about it. Some critics felt that the history – Occupied Paris – was rather didactically presented rather than being integrated in the narrative. But the stumbling block for me was rather that some of that history was wrong. Careless mistakes that Faulks or someone should have spotted. Does it matter? I think it really does – if you’re going to invoke this (still contentious and disputed) history, get the details right.

Karen Joy Fowler – We are all Completely Beside Ourselves (on my Decade list)*

Barbara Kingsolver – Flight Behaviour

Chris Mullins – The Friends of Harry Perkins (a late sequel to A Very British Coup)

Michael Ondaatje – The English Patient (another one that I hadn’t got round to for years, and that somehow didn’t connect with me. Whether that’s down to me or Ondaatje, I cannot tell…)

Georges Perec – W: Une Memoir d’enfance

Sally Rooney – Normal People (on my Century list)*

Liz Rosenberg – Indigo Hill (on my Century list)*

Donal Ryan – From a Low and Quiet Sea (on my Century list)*

Kit de Waal – The Trick to Time*

Biography and Autobiography

Sue Black – All that Remains: A Life in Death (musings on life and career from a leading forensic anthropologist)

George L Mosse – Confronting History (engaging autobiography of one of the leading historians of the Nazi era and ideology, himself a refugee from Nazi Germany)

Keith Richard – Life (on my Century list)*

Bart Van Es – The Cut Out Girl: A story of War and Family, Lost and Found(the story of one of the ‘hidden children’ in occupied Netherlands, and of the author’s family, who sheltered her)

Tara Westover – Educated (grim and fascinating autobiographical account of growing up in the Church of the Latter-Day Saints)

History

Ferdinand Addis – Rome: Eternal City (on my Decade list)*

Anne Applebaum – Iron Curtain (on my Decade list)*

Saul Friedlander – Nazi Germany and the Jews: The Years of Persecution, 1933-1939 (first of a two-part history by Friedlander, a refugee from Prague who survived the war as a ‘hidden child’ in France)

Anton Gill – An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler

Thomas Harding – The House by the Lake (on my Century list)*

Claudio Magris – Danube: A Sentimental Journey from the Source to the Black Sea* (inspired by my cruise up part of the Danube. Magris does the whole river, as the title suggests, and his journey predated the lifting of the Iron Curtain, so it was fascinating to contrast his impressions with my own)

Renée Poznanski – The Jews in France during World War II

Michael Rosen – The Disappearance of Emile Zola: Love, Literature and the Dreyfus Case (a fascinating, touching and often quite funny account of the great novelist holed up in various hotel rooms in England, suffering the dreadful food – he is baffled by gravy: why roast meat and then pour water on it? – and trying to juggle his complicated domestic arrangements. Obviously, Rosen also gives plenty of insight into the Dreyfus Affair which prompted Zola’s exile – and probably his murder).

Other Non-Fiction

David Andress – Cultural Dementia: How the West has Lost its History, and Risks Losing Everything Else (I only came across this because I follow Andress on Twitter and find his contributions there to be so well-informed and incisive that I wanted to read more of his thinking about the state of things. As the blurb suggests, it’s not exactly an optimistic view, but vitally important if we’re to understand how to fight back.)*

Billy Bragg – Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World*

Nicci Gerrard – What Dementia Teaches us about Love (on my Century list)*

Dave Rich – The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism* (this made a lot of sense, for me, of the specific nature of left-wing anti-semitism. Unless we understand this, we are trapped in endlessly asserting people’s anti-racist credentials as if that should be sufficient response, or whataboutery focusing on the Islamophobia of the Tory party.)

Rebecca Skloot – The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks* (on my Century list)

Postscript – what I read after I posted this:

- Ben Aaronovich – Lies Sleeping

- Claire Askew – All the Hidden Truths

- James Baldwin – If Beale Street could Talk

- Chris Brookmyre – Places in the Darkness

- Viet Dinh – After Disasters

- Louise Doughty – Platform Seven

- Tana French – The Secret Place

- Elly Griffiths – Now You See Them

- Philip Kerr – Metropolis

- Jane Lythell – After the Storm

- Liz Rosenberg – Beauty and Attention

Allons-y to 2020, to new new books and new old books, e-books and tatty paperbacks, books that make me laugh, that make me cry, that make me think.

And to all the writers who’ve brought me so much enjoyment and enlightenment in 2019, my thanks, my love and admiration.

To Hell in a Handcart

Posted by cathannabel in Brexit, Politics on December 15, 2018

Seems to be where we’re heading. I do try, really I do, to retain some optimism, some faith and some hope. I think I’m just weary now, of hoping that some coherent opposition will emerge, hoping for evidence of a truly significant shift in public opinion (here and in the US), hoping that the bad guys won’t win this time.

That doesn’t mean I’ve given up – I’m at a low ebb for personal reasons, and that’s sapped my capacity to muster up some positive thoughts.

(The other thing, of course, that militates against my traditional end-of-year musings on the state of the world, is that by the time I have drafted anything events will have moved on, for better or (more likely) for worse, and I’ll have been left behind by them.)

To paraphrase Brando in The Wild One: “What are you despairing about?” “What you got?”

Brexit (obvs) – is it even going to happen? I desperately want it not to happen but so much damage and division has already been created that it isn’t a straightforwardly comforting thought that there might yet be a way that we can Remain.

If it does happen, there will be, I believe, a very great deal more long term damage, and much more profound division. It’s not the consequences for me personally that concern me, it’s about the consequences for all of us. But most particularly for European citizens in the UK, for anyone ‘foreign’ in the UK, for my kids’ generation whose opportunities will be so curtailed, for the poorest who will be hardest hit by recession and tightened austerity, for the sick who will suffer as the NHS runs out of resources.

I am fearful, and I’m sad. I recently travelled up the Danube on a cruise ship – our hotel manager and tour managers were from Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary respectively, our tour guides were from Budapest, Vienna, Salzburg, Bratislava. All of them mentioned Brexit, and the tone was one of bafflement, of regret, of hurt (‘You don’t want us any more’).

I’m also angry because this whole mess could have been so easily avoided. If the referendum had been clearly and publicly stated to be advisory (as it legally was), if under-18s had been enfranchised (as in the Scottish independence referendum), if EU citizens resident in this country and UK citizens long-term resident in Europe had been able to vote, then the outcome might well have been what the majority of MPs and Cabinet members hoped it would be. If, when the result was known, the powers that were had said, ‘OK, we weren’t expecting this and we haven’t exactly planned for it, but now we know that is the view, we will put together a cross-party team of the very best minds we have (yes, ‘experts’), and work out how we can do this without damaging the country. If we conclude there is no way, we will revisit the outcome, having made our findings known to Parliament and to the nation’… But that would have taken courage and integrity, qualities in woefully short supply.

Instead, those tasked with negotiating our exit have demonstrated no understanding of the issues, no aptitude for negotiation. They’ve faffed and fannied about for two and a half years. They’ve been smug and arrogant and dishonest. The only consistent thing has been the way in which everyone is to blame other than them, the EU, the ‘unapologetic Remoaners’, the business community, everyone. And at this late stage, our hapless and hopeless PM is reduced to desperate pleading with EU leaders, and – because she really can’t help herself – pronouncing even in those last ditch meetings, as if it means anything at all, that ‘Brexit is Brexit’.

That’s just us. But wherever we look we see the same, or worse, sometimes much, much worse. Where do we look for comfort and hope?

As always in dark times there are people striving to bring light. As always when the haters are out in force there are people speaking truth and love. As always when there’s mess there are people who will move heaven and earth to clean it up. The light-bringers, the truth-sayers, the open-hearted, the problem solvers may not hold power but we have to hope they have influence, that their voices will be heard, in all the parts of the world where they’re most needed.

It’s been a while since I posted anything here at all, and I’d really rather that I could have broken the silence with something stronger, something more uplifting and positive. But that’s all I’ve got, folks, right now.

“Hang on to your hat. Hang on to your hope. And wind the clock, for tomorrow is another day.”

― E.B. White

#NHS70

Posted by cathannabel in Personal, Politics on July 6, 2018

October 1990, I’m expecting my first child. After a straightforward pregnancy, we’re now getting slightly anxious that the baby is overdue and no signs that he/she is going to make an appearance without intervention. I’ve got a NCT birth plan and everything, but once the process of induction is underway that goes out of the window. I work my way up through the hierarchy of pain control, barely bothering with the gas and air, quite enjoying the pethidine until it ceases to really touch the edges of the pain. Epidural now, that does the trick. Blissful moments of peace. But still no baby, so we’re now looking at a Caesarean, and I’m conscious but pain-free as they lift him out of my belly.

Pain and exhaustion and bliss all at once. A few weeks later, at home with our son, and he’s crying all the time. Really, all the time. Nothing seems to make it better. I don’t know whether there’s something wrong, or I’m doing it wrong, but then at the 8 week check-up at the GPs, we find out that he’s lost weight. The baby books are full of reassurances that you shouldn’t panic if your baby hasn’t gained as much as the charts say, but none of them tell us that we shouldn’t panic if he has lost weight. Next day I’m at the maternity hospital for a post-C-section checkup and hand the baby to a nurse whilst they examine me. My consultant sees him and tells us to go to the Children’s Hospital A&E. Now. Don’t go home first. We head straight there and the baby and I don’t leave for a fortnight.

The consultant is baffled, but we’re taken care of and I’m looked after when I go down with a tummy bug a few hours after we’re admitted. And soon they’ve got the baby on medication and he’s starting to recover – turns out his adrenal gland either never kicked in when he was born, or stopped working, and so those hormones need to be replaced artificially. He also has to have a minor op to correct vesicoureteric reflux which is causing recurrent UTIs (one of which may have triggered the adrenal shutdown).

Once he’s settled on the meds he’s a different baby. We have a regime of medication, and an emergency kit to inject him if he has an accident or something that might provoke another shutdown, given that his meds are just keeping him at normal hormonal balance, not fight or flight levels (we never used it). He’s got regular outpatients appointments to check on his progress, and when he’s eighteen months old he goes back into hospital and is taken off the meds to see how he responds. Amazingly, his adrenal gland kicks straight in, and whilst no one can fully explain what went wrong and then what went right, he’s now a healthy small person, albeit with one kidney that’s just at the lowest level of functionality. The hospital keeps on monitoring him for several years, and whilst we continue to be anxious for a while, gradually we learn not to be. We are, as he is, incredibly and for ever grateful for the NHS staff who spotted that there was a problem and then put in place all the resources to solve it.

That is the most dramatic #NHS70 story we’ve got. But our reliance on the system has continued. It saw us through the birth of our daughter, a problematic delivery after which I needed a blood transfusion (which, ironically, is the reason both why I so much wanted to donate blood myself, and why I can’t). Between the four of us we’ve sampled pretty much all of the various outpatient clinics at the Children’s/Royal Hallamshire/Northern General. Appendicitis, type 2 diabetes, asthma, hypertrophic cardiac myopathy, hypersomnia, depression, and all the usual ear/chest infections, minor injuries, plus breast screening, smear tests, bowel cancer screening, blood tests, diabetic check-ups, retinal neuropathy screening… We’ve had help from a panoply of GPs, practice nurses, consultants, registrars, hospital nurses, physiotherapists, healthcare assistants, surgeons and counsellors.

We’ve got so many reasons to be grateful – we know that the system is over-stretched, we know that there’s a problem where medical treatment and social care intersect (or should), and of course not all consultants, nurses, GPs, healthcare assistants or therapists are as helpful, as good at listening, as each other.

But whilst it’s under-resourced, and whilst the quality of treatment will vary from area to area, from person to person, and from medical condition to medical condition, some things are constant.

We’ve had our share of worry – from the paralysing terror of losing a baby to the niggling anxiety that this lump or that twinge might presage something serious. But we’ve never had to worry about whether or not we could afford to get that niggle checked out. We’ve never had the fear that the cost of treatment would drive us into debt. We’ve always known that it’s there for us.

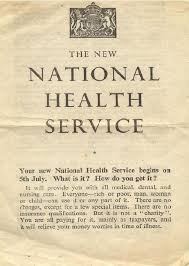

It’s original core principles were:

- that it meet the needs of everyone

- that it be free at the point of delivery

- that it be based on clinical need, not ability to pay

Those principles have been expanded upon over the last seventy years, as society has changed, and as our understanding of what ‘the needs of everyone’ might entail has deepened. But fundamentally, what we as a family have called upon when we needed it is the NHS as Nye Bevan envisaged it. It’s met our needs. It’s been free at the point of delivery. And it has never, ever, given a damn about our ability to pay.

To those across the pond who talk of NHS death panels whilst so many of their citizens avoid seeking medical help for fear of the medical bills – check your facts, and check your privilege. If your citizens really understood what we have here, they would want it for themselves, and they would be willing to pay for it through taxation, if they knew that they would never again have to fear the cost of treatment.

To those closer to home who want the service to die the death of a thousand cuts, to point to its deficiencies as evidence that it doesn’t work, to privatise it bit by bit until those core principles no longer mean a damn thing – know this, we will fight you every step of the way. We have something precious and we won’t let you take it away.

To the NHS, and all who work within it, thank you, we love you. And Happy Birthday.

Remainers Assemble

Posted by cathannabel in Brexit, Politics on January 15, 2018

Funny how swiftly a mood can change. I wrote a fairly despairing piece about Brexit, just over a month ago. It was a bit of a rant, an expression of my deep frustration at not seeing a way forward, a way out of the mess.

And suddenly, just in the last few weeks, the thing that I didn’t dare hope for, that I want so badly, is being talked about openly.

Stopping Brexit.

It’s not straightforward, obviously. The loss of face for May & co. will ensure that they set their faces against it. And, sadly, Corbyn seems unlikely to come out as a Remainer and lead the charge against the government. I also know that if it is stopped, damage will already have been done, and recovery will take a long time.

But the tide does seem to be turning. Surprising numbers of people who want Brexit to happen, as well as people who want to ensure it doesn’t, are now saying ‘if’ rather than ‘when’.

Those of us who voted Remain have been told, over and over again, to shut up and accept it. To get over it. We’ve been called whingers, ‘snowflakes’, ‘Remoaners’. We’ve been accused of being traitors and saboteurs, of betraying the Will of the People. Some of us had death threats.

Funny kind of snowflake, that withstands the vitriol, the hate, the threats and keeps on keeping on. Because we had to call out the lies that tricked people into voting for Brexit, and the incompetence and ignorance that characterised the government’s attempts to negotiate with the EU.

We didn’t do that out of pique. We’ve kept on about it because we believe that Brexit is an act of national self-harm, and that whilst we will all pay dearly for it, those who will suffer its consequences most acutely are the most vulnerable in our society (the poor, those most in need of the NHS), and the young. We’ve kept on because we care about and love this country.

Whilst I do get tetchy about the assumption that it’s my age group that landed us in this mess, statistically there is some evidence for Brexit appealing particularly to a generation that can remember the old (blue? black? who knows/cares) passport, pre-decimal currency, imperial measurements, and all that nonsense. The people who got terribly agitated because Big Ben’s bongs might briefly be silenced. The people who want to return us to some fantasy version of the 1950s – post-rationing, pre-counter-culture.

But, to put it somewhat brutally, many of those who look back with such fondness to the past won’t be around by the time Brexit really kicks in. Whereas the generations that will have their freedoms curtailed by this ‘taking back of control’ will be losing so much and gaining what, exactly? A different coloured passport. Perhaps a crown crest on their pint glass.

I want freedom of movement, for myself and for my children and their children.

I want the economic benefits of EU membership, for myself and for my children and their children.

I want our nation to continue to be diverse, to embrace people from Europe (and beyond Europe) who can contribute to our economy, our culture, our health service, our education – and those who need asylum. I want those Europeans who have made their homes here to feel secure, to feel that they are indeed at home, and welcome.

I want to be part of Europe, part of that group of nations forged after horrific conflict, based upon shared values, facing shared challenges. The greatest challenges we face are global – terrorism, climate change, the flow of refugees from war zones and famine. Our best hope of dealing with them is to work closely with our neighbours, not to shut them out.

I am convinced that there are many people who voted Leave – for a wide variety of reasons – who now regret that choice. Many must have been horrified by the open racism that followed so swiftly on the vote, the abuse offered to anyone who appeared to be ‘foreign’, the glee with which they were told they didn’t belong here any more. Others have been dismayed by the disparity between what they were promised and what the government now says about what might be delivered, and the obvious disarray of those who are responsible for negotiating on our behalf. I am also convinced that there are many who didn’t vote, maybe because – like so many of us who voted Remain – they assumed Remain would win. If those who voted Leave and now regret it, and those who stayed at home on polling day and wish they hadn’t, were to join forces with those who voted Remain and still believe it was the right choice…

So, strengthened by the solidarity of on-line communities that are pressing for an exit from Brexit, I will not only not shut up but will go on, and on, and on, relentlessly, until we find a way of stopping this madness.

And my vote – at local and national level – will go only to those who are pledged to the same cause.

A Manifesto for Europe

The EU was built on the words of Winston Churchill. It was founded on the same values that we recognise as British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and mutual respect.

The European Union has enabled neighbouring nations to overcome historic differences, create new alliances and build bridges where previously there were walls.

For the past 70 years, the United Kingdom has enjoyed peace, prosperity and enhanced standing in the world as a result of its role at the heart of the European Union.

We believe:

- In democracy and the rule of law.

- In the sovereignty of the UK Parliament.

- That the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union amplifies the rights, freedoms and interests of the British people.

- That UK and EU law underpin our economic, social and political rights.

- That the UK can only be truly global and outward facing as a fully committed member of the European Union.

- That the life prospects of young people and future generations of British citizens are augmented by continued UK membership of the EU.

- That the four nations of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland are stronger when united as a sovereign country, and as a member of the European Union.

- That continued UK membership of the EU is necessary to ensure the UK is relevant and effective in tackling global challenges such as climate change, terrorism, the displacement of peoples, and global economic adversity.

We reject:

- All forms of hate, racism and xenophobia that have been exacerbated by the referendum campaign and ballot.

- Nationalist protectionism, imperialism and isolationism.

- Treating EU nationals, EU member states and the EU itself as our enemies rather than our friends

A strong, free and united European Union, with Britain at its heart, is capable of facing up to the challenges of today and tomorrow, and of playing a leading role in championing international peace and prosperity.