W G Sebald’s novels tend to begin with someone setting out on a journey. His protagonists are almost always in transit, and if they do settle somewhere it is not likely to be long-term. There are always exceptions, of course, and Max Ferber (The Emigrants) is the exception in relation to the latter trait – once he finds himself in Manchester he feels he cannot, must not leave. But Jacques Austerlitz is the archetypal Sebaldian wanderer.

We (via the narrator, who both is and is not Sebald) meet Austerlitz first in Antwerp, then in Liege, Brussels and Zeebrugge, before finding out that he is based in London. At this stage his restless quests are related to his academic interests in architecture, particularly public architecture, as he explores railway stations, prisons and fortresses, courtrooms and museums. After a two year hiatus in their relationship, the narrator and Austerlitz encounter one another again, in London, in a railway station bar. Only now do we begin to find out about his early life. Until his teenage years he had believed himself to be Dafydd Elias, growing up in Bala in Wales. Only after the death of his foster mother and the mental breakdown of his foster father does he discover that his name is Jacques Austerlitz, but he knows nothing more. The name itself signals a kind of multiple identity – a French first name and a Czech place name (which, as a surname, was shared with Fred Astaire and which, because of the Napoleonic era battle which took place there, is also the name of one of Paris’s major railway stations).

Austerlitz finds himself obsessively walking the streets of London in the early hours, and is drawn back repeatedly to Liverpool Street Station where he has a kind of vision of himself as a small child, meeting for the first time the foster parents who had been assigned to him. He feels ‘something rending’ within himself and is in a state of mental torment until he hears, by chance, a radio broadcast about the Kindertransport. This begins to trigger memories of his childhood journey, and when he hears the name of the ship, ‘SS Prague’, he determines to go to that city and find out about where it began.

Austerlitz’s quest is now to find out who his parents were, and what happened to them. He discovers, or believes he has discovered, his mother’s fate. She was deported to Terezin, from whence she was taken, we understand, ‘east’. Whilst there are uncertainties about this narrative, there are far more surrounding his father, who had left for France before the deportations from Prague began.

And so to Paris. Alongside my mission to photograph all of the memorial plaques relating to WWII that we passed as we walked its streets, I wanted to find, if I could, some of the locations described in Sebald’s novel. Sebald sometimes describes real places with absolute precision, sometimes alters or relocates them. Of course, whilst major public buildings were easy to find, I was unsure whether, given that the narrator and protagonist are both fictional constructs, the specific addresses provided would be as straightforward. But they were all there, even the bistro on boulevard Auguste Blanqui.

I received a postcard from Austerlitz giving me his new address (6 rue des cinq Diamants), in the thirteenth arrondissement. (p. 354)

I met Austerlitz, as agreed, on the day after my arrival, in the Le Havane bistro bar on the boulevard Auguste Blanqui, not far from the Glaciere Metro station. (p. 355)

The rue Barrault is said to be the last known address of Maximilian Aychenwald. Austerlitz speculates about whether his father had been caught up in one of the round-ups of Jews:

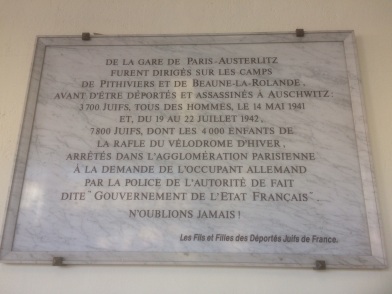

I kept wondering whether he had been interned in the half-built housing estate out at Drancy after the first police raid in Paris in August 1941, or not until July of the following year, when a whole army of French gendarmes took thirteen thousand of their Jewish fellow citizens from their homes, in what was called the grande rafle, during which over a hundred of their victims jumped out of the windows in desperation or found some other way of committing suicide. I sometimes thought I saw the window-less police cars racing through a city frozen with terror, the crowd of detainees camping out in the open in the Vélodrome d’Hiver, and the trains on which they were soon transported from Drancy and Bobigny; I pictured their journey through the Greater German Reich, I saw my father still in his good suit and his black velour hat, calm and upright among all the frightened people. (pp. 358-359)

During an earlier period in Paris, before the search for his father began, Austerlitz had had another episode of nervous collapse, and had been admitted to the Salpêtrière Hospital.

I did not return to my senses until I was in the Salpêtrière, to which I had been taken and where I was now lying in one of the men’s wards … somewhere in that gigantic complex of buildings where the borders between hospital and penitentiary have always been blurred, and which seems to have grown and spread of its own volition over the centuries until it now forms a universe of its own between the Jardin des Plantes and the Gare d’Austerlitz. (pp. 375-376)

This is the hospital at which, in the late 19th century, Charcot developed his diagnosis of ‘hysterical epilepsy’, and the phenomenon of the ‘fugueur‘ was first identified and researched. Austerlitz can remember nothing about himself or his history, but someone finds the address of his friend Marie de Verneuil and contacts her at 7 place des Vosges.

When I met Austerlitz again for morning coffee on the boulevard Auguste Blanqui, … he told me that the previous day he had heard, from one of the staff at the records centre in the rue Geoffroy l’Asnier, that Maximilian Aychenwald had been interned during the latter part of 1942 in the camp at Gurs, a place in the Pyrennean foothills … Curiously enough, said Austerlitz, a few hours after our last meeting, when he had come back from the Bibliothèque Nationale and changed trains at the Gare d’Austerlitz, he had felt a premonition that he was coming closer to his father. As I might know, he said, part of the railway network had been paralysed by a strike last Wednesday, and in the unusual silence which, as a consequence, had descended on the Gare d’Austerlitz, an idea came to him of his father’s leaving Paris from this station … I imagined, said Austerlitz, that I saw him leaning out of the window … After that I wandered round the deserted station half dazed, through the labyrinthine underpasses, over foot-bridges, up flights of steps on one side and down on the other. That station, said Austerlitz, has always seemed to me the most mysterious of all the railway terminals of Paris. … I was particularly fascinated by the way the Metro trains coming from the Bastille, having crossed the Seine, roll over the iron viaduct into the station’s upper storey, quite as if the façade were swallowing them up. And I also remember that I felt an uneasiness induced by the hall behind this façade, filled with a feeble light and almost entirely empty, where on a platform roughly assembled out of beams and boards, there stood a scaffolding reminiscent of a gallows … an impression forced itself upon me of being on the scene of some unexpiated crime. (pp. 404-407)

The records centre in the rue Geoffrey l’Asnier is now the Mémorial de la Shoah. Amongst the many records kept here, there is a room full of boxes of index cards, relating to the various internment camps and those who were imprisoned there.

I don’t know, said Austerlitz, what all this means, and so I am going to continue looking for my father, and for Marie de Verneuil as well. (p. 408)

We will never know the outcome, although it seems most likely that his parents’ journeys ended in the same, terrible place, a place with which Austerlitz’s name has resonated, whether we have been conscious of it or not, from the beginning. As James Wood points out:

And throughout the novel, present but never spoken, never written – it is the best act of Sebald’s withholding – is the other historical name that shadows the name Austerlitz, the name that begins and ends with the same letters, the name which we sometimes misread Austerlitz as, the place that Agata Austerlitz was almost certainly ‘sent east’ to in 1944, and the place that Maximilian Aychenwald was almost certainly sent to in 1942 from the French camp in Gurs: Auschwitz.

(James Wood, ‘Sent East’, London Review of Books, 6 October 2011)

Austerlitz himself will continue to wander, and it seems that his travels are not merely in space, but also in time. The small Czech boy separated from his parents, the troubled Welsh schoolboy, the London academic, and the driven man travelling through some of the most haunted places in Europe – all are one. Always in transit, in temporary or liminal spaces, descending into the underworld/labyrinth to keep the appointment he has made with his own past.

He had quite often found himself in the grip of dangerous and entirely incomprehensible currents of emotion in the Parisian railway stations, which, he said, he regarded as places marked by both blissful happiness and profound misfortune. (p. 45)

I have always resisted the power of time out of some internal compulsion which I myself have never understood, keeping myself apart from so-called current events in the hope, as I now think, said Austerlitz, that time will not pass away, has not passed away, that I can turn back and go behind it, and there I shall find everything as it once was, or more precisely I shall find that all moments of time have co-existed simultaneously, in which case none of what history tells us would be true, past events have not yet occurred but are waiting to do so at the moment when we think of them. (p.144)

I felt, … said Austerlitz, as if my father were still in Paris and just waiting, so to speak, for a good opportunity to reveal himself. Such ideas infallibly come to me in places which have more of the past about them then the present. For instance, if I am walking through the city and look into one of those quiet courtyards where nothing has changed for decades, I feel, almost physically, the current of time slowing down in the gravitational field of oblivion. It seems to me then as if all the moments of our life occupy the same space, as if future events already existed and were only waiting for us to find out way to them at last. … And might it not be, continued Austerlitz, that we also have appointments to keep in the past, in what has gone before and is for the most part extinguished, and must go there in search of places and people who have some connection with us on the far side of time, so to speak? (pp. 359-360)