Archive for September, 2019

Marks of Pain: Architecture as Witness to Trauma in W G Sebald’s Austerlitz

Posted by cathannabel in Genocide, History, Second World War, W G Sebald on September 10, 2019

This is an edited version of a talk given at the 2019 Conference, Violent Spaces, of the Landscape, Space & Place group from the University of Nottingham.

Few late twentieth-century writers are held in such regard as W G Sebald. His work has inspired not only glowing reviews and a host of journal articles, edited volumes and monographs – but also responses by visual artists and filmmakers. There are certain themes that are most often associated with his work – time, loss, trauma, memory… These themes inevitably link to one particular aspect of his work – his writing about the Holocaust.

W G Sebald was born in Bavaria in 1944, in the last months of the war. His father had served in the Wehrmacht, but after he returned home, having spent a couple of years as a prisoner of war, the things that he had seen, and done, were never spoken of. And when Sebald as a teenager was shown documentary footage of the camps (probably the liberation of Belsen) no context or commentary was provided. It was, in a way, what we’d now call a box-ticking exercise. Because, of course, the teachers were part of the context. Sebald, like many of his contemporaries, was unable to accept this collusive silence, and his increasing alienation from his homeland led to him working first in Switzerland and then moving to the UK, where he spent the rest of his life, teaching at UEA until his death in a car accident in 2001.

The Holocaust, indeed, became a presence in his poetry and his prose writing. It seems never to be very far away, invoked maybe by the name of a place, innocent in itself, but carrying the weight of history. In many of his works, it is addressed obliquely, but the figure of the refugee appears in several of his books. Max Ferber, one of the four protagonists of The Emigrants, left his home in Munich (capital of Bavaria) in 1939, following Kristallnacht, his father having obtained a visa for him by bribing the English consul. We are introduced to Ferber via the narrator, who does not ask about his history, why or how he left Germany, until their second meeting, at which point Ferber tells how letters from his parents ceased, and he subsequently discovers that they were deported from Munich to Riga, where they were murdered. In Sebald’s final work, Austerlitz, the Holocaust becomes text, not subtext, foreground rather than context.

Sebald’s (fictional) protagonist, Jacques Austerlitz, is an architectural historian, with a particular interest in what he calls ‘our mightiest projects’ – fortifications, railway architecture, what they used to call lunatic asylums, prisons and law courts.

He’s also fascinated by the idea of networks, such as ‘the entire railway system’. From the outset, whilst Austerlitz himself does not make any connection between these edifices and the event that shaped his life, we are given foreshadowing of that event. He says of railway stations, for example, that he can never quite shake off thoughts of the agonies of leave-taking – and we’ll see the significance of that later. He refers to ‘the marks of pain which, as he said he well knew, trace countless fine lines through history’.

We meet the narrator first in a carceral space – Antwerp’s zoo. After his first conversation with Austerlitz, he is moved to visit Breendonk, one of the fortresses that Austerlitz had mentioned.

But it is not the history of how such places were designed, the flawed theories of defence against enemy incursion, that confront him there, but the much more recent past, Breendonk’s conversion into a concentration camp in the Nazi era – a transit camp for deportation to Auschwitz, and a place of torture.

- Originally built for the Belgian army 1906-13 to protect Antwerp – ‘it proved completely useless for the defence of the city and the country’

- Covered by a five-metre thick layer of soil for defense against bombings, a water-filled moat and measured 656 by 984 feet (200 by 300 m)

- Requisitioned by the Germans as a prison camp for political dissidents, captured resistance members and Jews

- Infamous for prisoners’ poor living conditions and for the use of torture. Most prisoners later transferred to larger concentration camps in Eastern Europe

- 3,590 prisoners known to have been imprisoned at Breendonk, 303 died or were executed within the fort itself and as many as 1,741 died subsequently in other camps before the end of the war

Sebald brings in a human witness here, Austrian writer Jean Amery, who was interned and tortured at Breendonk before deportation to Auschwitz and later Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen. He survived, changed his name from the obviously Germanic Hans Meyer, but committed suicide in 1978.

Our narrator finds Breendonk to be a place of horror. The darkness inside is literal, but also metaphysical, and it becomes heavier as he penetrates further into the building. He begins to experience visual disturbances – black striations quivering before his eyes – and nausea, but explains that ‘it was not that I guessed at the kind of third-degree interrogations which were being conducted here around the time I was born’, since he had not at that point read Amery’s account. Sebald is telling us that the narrator’s reaction to Breendonk is not, therefore, personal, not related in any way to his own experiences or even to things he had read, but intrinsic to the place, as if its use, or abuse, has changed its very nature, violence become part of its fabric.

Breendonk is the first of the trio of Holocaust sites around which the text is structured. It’s built to a star shape, a six-pointed star. This was a favoured design both for fortresses, designed to keep invaders out, and for prisons, designed to keep wrongdoers in.

According to Austerlitz this is a fundamentally wrong-headed design for a fortress, the idea that ‘you could make a city as secure as anything in the world can ever be.’ The largest fortifications will attract the enemy’s greatest numbers, and draw attention to their weakest points – not only that, but battles are not decided by armies impregnably entrenched in their fortresses, but by forces on the move. Despite plenty of evidence (such as the disastrous Siege of Antwerp in 1832), the responses tended to be to build the same structures but stronger and bigger, and with inevitably similar results.

As the design for a prison, the star shape makes more sense. It does not conform to the original layout of the panopticon, but it does allow for one central point of oversight and monitoring, with radial arms that separate the inmates into manageable groups. The widespread use of existing fortresses as places of imprisonment for enemies of the Reich was primarily opportunistic, of course, but the ease of this transformation illustrates Austerlitz’s arguments quite well.

Sebald had previously been struck by his encounter with Manchester’s Strangeways prison, which has the same shape, ‘an overwhelming panoptic structure whose walls are as high as Jericho’s’, and which happens to be situated in the one-time Jewish quarter. The coincidence of the hexagram star is implicit in the above. But it becomes entirely explicit when we look at the second of Sebald’s sites, Terezin.

- Some 70 km north of Prague

- Citadel, or small fortress, and a walled town, known as the main fortress – never tested under siege

- The small fortress became the Prague Gestapo police prison in 1940, the main fortress became the Ghetto in 1941

- Initial transport of Czech Jews, German and Austrian Jews in 1942, Dutch and Danish in 1943, various nationalities in the last months of the war as other camps were closed

- c. 141k Jews, inc. 15k children, held in the Ghetto 1941-1945. 33k died there (disease/malnutrition), 88k deported to Auschwitz, 23k survivors

This lies at the heart of his narrative. Austerlitz, as we discover gradually through the narrator’s irregular meetings with him, came to Britain on the Kindertransport from Prague in 1939, when he was not yet five years old. He was met at Liverpool Street Station by a couple, a minister and his wife from Wales, who fostered him, giving him a new name, and telling him nothing of his history. A teacher tells him his real name when he is in his teens, but rather than this prompting a search for his origins, Austerlitz turns away from his own past and consciously avoids any sources of information which might bring him too close to it. Thus, when he talks to the narrator about Breendonk, it is its history in the first, rather than the second war that he mentions.

Much later, after a strange encounter with his childhood self in the Ladies Waiting Room at Liverpool Street Station, by chance he hears a radio programme about the Kindertransport, and has a kind of epiphany, which prompts him to go to Prague and search for his family. He discovers that his father fled Prague for France, just ahead of the Nazi invasion, and that his mother, left alone there after the train had taken her child to safety, was deported to Terezin from where she was ‘sent east’, presumably to Auschwitz and presumably to her death.

Terezin shares many characteristics with other Nazi concentration camps. But there are elements of its history that mark it out. It was not a labour camp – it was presented as a ‘retirement settlement’ for elderly and prominent Jews, and its role was propaganda rather than economic, discouraging resistance to deportation with promises of comfort, and encouraging wealthier Jews to bring their valuables (of which, naturally, they were relieved on arrival). It was not a death camp – though the terrible conditions led to around 33,000 deaths from malnutrition and disease – but was a way station to Auschwitz. The particular make-up of the population of Terezin led to a rich cultural life, with music in particular playing a leading part.

However, the most notable feature of Terezin was that it was a ‘Potemkin village’, a place whose real purpose could be easily disguised. Indeed it was disguised in 1944, ready for a Red Cross visit, where it was presented as an ideal Jewish settlement. Overcrowding was addressed by the simple expedient of deportation, particularly of the less photogenic inhabitants, the old, sick and disabled. The place was cleaned up, shop fronts erected, and cultural and sporting activities organised for the prisoners. A film was made, which shows football matches and concerts, smiley, healthy looking people. The Red Cross appear not to have realised that they were being duped. Once they had left, of course, deportations were resumed.

W G Sebald, Austerlitz, pp. 266-68; H G Adler, Theresienstadt 1941-1945: The Face of a Coerced Community

‘I felt that the most striking aspect of the place was its emptiness, said Austerlitz […] the sense of abandonment in this fortified town, laid out like Campanella’s ideal sun state to a strictly geometrical grid, was extraordinarily oppressive, yet more so was the forbidding aspect of the silent facades.[…] What I found most uncanny of all, however, were the gates and doorways of Terezin, all of the, as I thought I sensed, obstructing access to a darkness never yet penetrated’

Austerlitz visits Terezin, having learned of his mother’s imprisonment there. He has been told that it is an ordinary town now, but he finds it strikingly empty, its streets deserted, its windows silent and blank. In its museum, he is confronted by the history he has been avoiding for so long – he studies the maps of the German Reich, in particular the railway lines running through them, that facilitated forced labour, deportations and genocide. The ground plan of the star-shaped fortifications is ‘the model of a world made by reason and regulated in all conceivable respects’, a fortress that has never been besieged, a quiet garrison for two or three regiments and some 2,000 civilians. But it seems to Austerlitz that, far from having returning to this civilised and reasonable state, the town is now filled with the people who had been shut in to the ghetto, as if ‘they had never been taken away after all, but were still living crammed into those buildings and basements and attics, as if they were incessantly going up and down the stairs, looking out of the windows, moving in vast numbers through the streets and alleys and even, a silent assembly, filling the entire space occupied by the air’.

Our human witness to Terezin is H G Adler, who, like Austerlitz, was born in Prague. He was sent initially to a labour camp in 1941, then to Terezin with his family in 1942. In 1944, he, his wife and her mother were deported to Auschwitz, where both women were murdered on arrival. Adler also lost his own parents and many other members of his family. From Auschwitz, he was deported to two successive sub-camps of Buchenwald before liberation. His research post-war focused on the archives of Terezin and formed the basis of his major work, Theresienstadt 1941-1945, which Sebald quotes and refers to extensively and which is still the most detailed account of any single concentration camp.

There’s one more fortress to consider. Kaunas, in Lithuania.

- 12 forts built in 19th century to defend against German armies

- All surrendered in 1914 and some fell into disuse

- Russians occupied in 1939 and used them as prisons

- 1941-45 German occupation: 7th fort used as concentration camp – 4k Jews killed there. 9th fort was execution and burial site for Jews from Kaunas and for other Jews shipped there during the Holocaust

- Abraham Tory reports in his ghetto diary that ‘single and mass arrests as well as “actions” in the ghetto almost always ended with a death march to the Ninth Fort, which in a way completed the ghetto area and became an integral part of it‘

We have no first-hand human witness here. Instead, we have Dan Jacobson, a South African writer whose book Heshel’s Kingdom describes his attempts to piece together a family narrative fragmented by history, the fate of whose members was determined by one event, the sudden death of Heshel Melamed in 1919, which freed his widow, children and grandchildren to emigrate from Lithuania to South Africa. Jacobson’s quest is to discover what happened to the other branches of the family, those who were left behind.

W G Sebald, Austerlitz, pp. 414-15, Dan Jacobson, Heshel’s Kingdom, pp. 159-62

Jacobson tells us that the Russians built a ring of twelve fortresses […] in the late nineteenth-century, which then in 1914, despite the elevated positions on which they had been constructed, and for all the great number of their cannon, the thickness of the walls and their labyrinthine corridors, proved entirely useless. […] In 1941 they fell into German hands, including the notorious Fort IX where Wehrmacht command posts were set up and where more than thirty thousand people were killed over the next three years.[…] Transports from the west kept ]coming to Kaunas until May 1944,[…] as the last messages from those locked in the dungeons of the fortress bear witness. One of them, writes Jacobson, scratched the words “Nous sommes neuf cents Francais” on the cold limestone wall of the bunker.

Neither Austerlitz nor the narrator visits Kaunas. But Austerlitz gives to the narrator, before he sets off to continue his own quest for answers, a copy of Jacobson’s book. Sebald’s narrative leaves us at the end of Jacobson’s Chapter 15, in an underground corridor where, behind glass, are preserved the ‘wall scratchings’ – literal marks of pain – of French Jewish prisoners brought here – after the war had effectively been lost. These include Max Stern, Paris, 18.5.44 – Sebald’s first name, and his date of birth; the fictional Austerlitz’s father’s first name, and last known location. What happened to these people, what happened to Jacobson’s family, cannot be known. Were they deported to an extermination camp – perhaps more likely, given the history of Kaunas, were they were killed right there?

Auschwitz is, of course, the fourth location that is implicit in the above.

It is both the archetype – we invoke this name above all others to stand for the Nazi machinery of mass murder – and the specific journey’s end for so many. Sebald doesn’t take us there though – it is present, always, but unseen and its name unspoken. We hear it only as an echo – in the name of our protagonist, in the mention of the Auschowitz springs which he visits at Marienbad. We don’t go there because we don’t need to – the phrase ‘sent east’ is already heavy with meaning.

Sebald gives us not only these closed places of death and terror but their apparent opposite – the transitory, liminal space of the railway station. Austerlitz’s fascination with the railway network was always tinged with a sense of loss, anguish even. In this, he reminds us of Max Ferber from Sebald’s The Emigrants who finds railway stations and railway journeys to be torture and who as a result, never leaves Manchester. And perhaps Sebald also was thinking of the passage in Elie Wiesel’s autobiography, concerning ‘those nocturnal trains that crossed the devastated continent’:

Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea

Their shadow haunts my writing. They symbolise solitude, distress, and the relentless march of Jewish multitudes towards agony and death. I freeze every time I hear a train whistle.

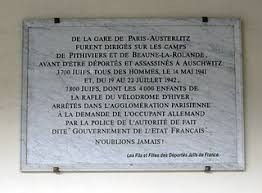

Towards the end of the narrative, at the Parisian railway station with which he shares a name, Austerlitz feels that he is ‘on the scene of some unexpiated crime’. Indeed, the Gare d’Austerlitz was the station from which Jews rounded up in the city were crammed into cattle trucks and transported to the transit camps near Paris – from where they were later crammed again into cattle trucks for transport to Auschwitz. And of course, one of the most often used images of Auschwitz itself is of the railway tracks.

Austerlitz pieces together his mother’s journey, after her partner and then her son leave.

She is ordered to report to the Prague Exhibition Centre with her belongings. She and her fellow deportees go to Holesovice station and from there by train to Bauschowitz station, from where they must walk to Terezin. From Terezin, at some unknown date, another train takes her to Auschwitz.

His father’s journey is more speculative. Austerlitz knows that Max flew from Prague to Paris. After that, his mother had various addresses for him in Paris, but no communications. Austerlitz wonders whether he was rounded up in 1941, in the first wave of arrests of foreign Jews, or in the much bigger round-up in July 1942, the Vel d’Hiv, the first round-up to take not only men capable of work but women, children, the sick, the elderly. Austerlitz also learns that Max may have been at one time at the Gurs camp in southwestern France, originally set up for Spanish refugees after Franco’s victory, but appropriated by the Nazis for Jews and members of the resistance. Did he die there, of disease or malnutrition? If not, was he deported from Gurs to Drancy and from there to Auschwitz? Or was he taken from the streets of Paris via the Gare d’Austerlitz to Pithiviers or Beaune-la-Rolande, and from there to Auschwitz? We take our leave of Austerlitz as he prepares to continue the search for evidence.

Sebald does recount another train journey. One which ended on the threshold not of death but of the hope of a new life. Austerlitz as a child travels from Prague’s Wilsonova station with the Kindertransport, a series of initiatives undertaken between Kristallnacht and the outbreak of war to get children, mainly Jewish, out of Nazi Europe – around 10,000 were thereby saved during that brief window of possibility. Jacques travels through Czechoslovakia and Germany, to the Hook of Holland, from where he takes the ferry to Harwich and another train to Liverpool Street Station. This is no fairy tale – for the fictional Jacques as for so many of the children, their assimilation and acceptance of their new home (a new language, new customs, often a new name, and a new religion) and their new family’s understanding of them, were problematic. And all of them faced traumatic absences, losses that they couldn’t grieve, and questions they couldn’t answer. Most never saw their parents again.

Austerlitz’s new life, the one that started on the platform at Liverpool Street Station, would never be free of those marks of pain. His academic quest to make sense of the family likeness between ‘monumental’ buildings, places that impose and imprison, and of the railway network that links them, has been superseded by the unrecognised need that had originally driven it. To find his family, to know everything he can know about their lives and their deaths, to inscribe those human stories, his human story, on the bricks and stones of the fortresses, prisons and railway stations that witnessed them.

(Austerlitz, p. 183)

‘I often wondered whether the pain and suffering accumulated on this site over the centuries had ever really ebbed away, or whether they might not still, as I sometimes thought when I felt a cold breath of air on my forehead, be sensed’

Bibliography

W G Sebald, Die Ausgewanderten (Fischer, 1992), English translation, The Emigrants, published 1996

__, Nach der Natur (Fischer, 1995), English translation, After Nature, published 2002

__, Austerlitz (Fischer, 2001), English translation published 2001

H G Adler, Theresienstadt 1941-1945: The Face of a Coerced Community (Cambridge UP, 2017)

Jean Amery, At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and its Realities (Indiana UP, 1980)

Dan Jacobson, Heshel’s Kingdom: A Family, a People, a Divided Fate (Hamish Hamilton, 1998)

Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea (Schocken Books, 1994)

Disintegration Loops

Posted by cathannabel in mental health, Music, Personal on September 5, 2019

This post has been many months in the gestation. In my head, it started off as a more abstract and metaphysical musing about the nature of dementia, at least as I have encountered it, about how what made a person that person fades, gradually, until it has virtually disappeared, and yet they are still here. As a recent contributor to a discussion in the Guardian described it, ‘death on the installment plan, as every day another little piece would flicker out of existence’. But there are other things that must be said as well – the anger at how our health service and social care – and in particular the failure to join the two up effectively – can fail those rendered helpless by the disintegration of their mind and memory.

The title is borrowed from a series of pieces of 21st century music, by American composer William Basinski, which I have loved ever since a friend introduced me to them a few years after they were released in 2002/03. Basinski had magnetic tapes, recorded in the 1980s, which he wanted to transfer to digital format. But the tapes had deteriorated, so there were gaps, and cracks, which increased as he continued to play the tapes. The original recordings can be heard, but faint, distorted, broken up, fragmented. And somehow this is intensely moving. When I first heard it, I felt the general sadness of loss, of gradual loss in particular, not a sudden shock and wrench but the knowledge that something is slipping away that was and still is precious. And when I saw this happening to someone I loved, that title and the memory of listening to these albums came back to me.

And the idea of loops, of course, resonated with us. The endless loops of conversation: Where am I? You’re in hospital, Mum, you had a stroke. Oh. When can I go home? When you’re stronger. Where am I? round and round again… As the disease progressed the loops got shorter, until all that was left were the questions and our answers disappeared into the fog.

Basinski was not thinking of dementia when he created these pieces. They’re dedicated to the victims of the September 11 attacks in New York, which Basinski saw from the roof of his apartment in Brooklyn, the morning that he had completed the project. But as D H Lawrence said, trust the tale and not the teller. That Basinski associated the work with 9/11 does not prevent it from being also a powerful and poignant and heartbreaking account of a very different kind of loss.

There are as many different experiences of dementia as there are sufferers – and carers. I can only speak of our own, but there are elements in what we experienced that will be shared by many. Over the months since she died we have been gradually able to overlay the images of her the last time we saw her conscious – bewildered, afraid, unable to understand what we were saying to her, unable to smile, unable to recognise the photograph of her beloved little cat that we had brought as a gift – with the woman we had known before. That woman was funny, fiercely independent, interesting and interested, a traveller, a gardener, a musician, a teacher, a fan of detective novels and TV series, a lover of good food and wine. Dementia took all of that, little by little by little, but as we organised her funeral and started to get cards and letters from people who’d known her before, we saw her re-emerge from the shadows, heard the laughter that so many people had mentioned, literally heard her voice on a recording amongst the other members of the choir she sang in for many years.

But as we recovered some of those joyful memories, I thought about some of what had happened in the last year of her life, and I got angry. On her behalf, but also on behalf of the many, many people who suffer from dementia. Many are less fortunate than she was – she had the funds to choose (or for us to choose on her behalf) the kind of care she needed, and to not have to put up with sub-standard care (in fact, the carers who supported her in her own home until her stroke were wonderful, as was the care home that she moved to for the last six months of her life). She had family who were close enough at hand to be involved in her care, who were free to come over at short notice when needed, to spend time on hospital wards to talk to medics on her behalf. But despite all of this, and despite the loving and patient care on the wards from nurses and health care assistants, there was something terribly wrong.

If I could go back, knowing what I know now, I would interject in every discussion about her medical care and about options for discharge, to remind people that, whilst she had been admitted to hospital following a stroke, she had dementia, and that any decision about her care in hospital and about what happened once treatment was over HAD to take account of that. She could not cooperate in her own care. She removed the feeding tube that the hospital had inserted to ensure she did not aspirate and contract pneumonia, because she did not understand why it was there, she only knew it was unpleasant and uncomfortable. She tried (and occasionally succeeded) in removing the surgical collar that was needed after she fell and broke a couple of vertebrae in her neck – again, she did not know why she was wearing it, blamed the collar for the pain of the fracture. Her carers – at her home and in the care home – took her dementia into account. Staff on the wards largely did (they brought her food even if she’d said she didn’t want any and didn’t rush to take it away when she said she’d finished, understanding that seconds later she’d forget that she’d finished and have another go… ).

But when it came to preparing her for discharge, it was as if the need to free up a bed, once no further medical treatment was required, overrode other considerations. We get it, we really do, we know the NHS is overstretched, we know that hospitals can’t have beds taken up long-term by people for whom they can do nothing more. Nevertheless…

We were told how much her mobility was improving, and that with extra help for a while (equipment and additional carers) she would be fine at home. And so she was discharged. We were given a date for discharge, and a time, so planned to get there (we’re an hour’s drive away) well ahead, to sort the house out and get her shopping done. But she was delivered home much earlier and so we arrived to find her sitting, bewildered, on the sofa (where we knew and her carers knew not to let her sit, because it was so difficult to get her up from it). She had no idea how long she’d been there. We quickly realised that we, and she, were in a nightmare. We were as terrified as she was.

She would be alone for most of every day (carers came four times a day). She had forgotten, after a month in hospital, how to use her TV remote and could no longer read. She would be incontinent and thus sitting in her own waste for hours. She would be unable to change her position in the chair or the bed and thus would be at risk of pressure sores. She would be at risk of falling from her chair if she forgot that she could not get up, and tried to do so. She had forgotten how to use her ‘red button’ alarm and so if she fell would lie there until the next carer visit. She would be shouting out for help, hour after hour – she had no sense of the passing of time, and so would be convinced five minutes after a carer had left that she had been alone for hours already.

She had been promised physiotherapy, and the assumption seemed to be that she could learn, and get better at the limited means of mobility possible for her. But since the dementia took hold, she had been unlearning. Unlearning skills she had had for years, like how to dress herself, how to make a cup of tea. Her discharge took no account of this.

When the carers arrived they shared our alarm and dismay and decided that it was an unsafe discharge and that she should go back into hospital. Next day when we rang to see how she was, the nurse on the EAU said brightly how well she’d done on the rotunda and that she’d be ready for discharge soon. We headed straight over and prepared for a fight.

We pointed out that if one of us had had a stroke and lost mobility, and was discharged to live alone, we would of course be worried and miserable. But we could do something about the situation – ensure that books, radio, TV remote were within reach, keep in touch with the world via phone or laptop and talk to family and friends. We could look at the clock and know how long it would be before someone would visit. She had none of those resources.

We argued, we insisted that we could not accept her being sent home. And eventually someone said to us, what do you suggest then? And we said, well, we rather thought you might be able to offer us some advice and guidance on possible solutions. And just like that, we were put in touch with the social worker and the Age Concern contact, and were given details of suitable care homes, and within a few days, were arranging her discharge to a dementia specialist care home.

We’d never promised her that we wouldn’t ‘put her in a home’. But even if we had made that promise, we’d have broken it. What mattered was that she was safe, that someone was there 24 hours a day to take care of her, that they were able to keep her comfortable. And the language of ‘putting’ someone in a home is inherently prejudiced – we found the best care home we could for her, and we worked with the care home manager and staff to meet her needs as well as we could, just as we had worked with the carers who came to her home. We have no regrets about that – only about our naivety in our dealings with the hospital and our failure to remind them at every stage and in every discussion about her dementia.

The other thing that rapidly became apparent to us was that with every hospital admission, the dementia gained ground. This is borne out by statistics from John’s Campaign:

- One third of people with dementia who go into hospital for an unrelated condition NEVER return to their own homes

- 47% of people with dementia who go into hospital are physically less well when they leave than when they went in

- 54% of people with dementia who go into hospital are mentally less well when they leave than when they went in

John’s Campaign‘s raison d’etre is pretty simple – the belief that in all hospital settings, for patients with dementia, ‘carers should not just be allowed but should be welcomed, and that a collaboration between the patients and all connected with them is crucial to their health and their well-being’.

In that grey area, where someone may be deemed to ‘have capacity’ to make decisions, but at the same time is unable to hold on to even simple information, let alone weigh up pros and cons, the family (if the patient is fortunate enough to have family/carers who are able and want to be involved) must be seen, surely, as a tremendous benefit for the hospital.

John’s Campaign applies to all hospital settings: acute, community, mental health and its principles could extend to all other caring institutions where people are living away from those closest to them. In the time since the campaign was founded, over 1000 institutions have pledged support and a lot of progress has been made – but there is a lot yet to be done.

https://johnscampaign.org.uk/#/about

If a patient with dementia has no family to speak for them, to ensure that their dementia is taken into account in all decisions about their medical and social care, how can we provide them with advocates? As Nicci Gerrard said in a recent article, dementia is our collective responsibility. You might not have encountered it yet. But odds are, you will. It’s in all of our interests that we recognise the scale of it, recognise what’s needed to keep people with dementia as safe and as comfortable as possible, that those of us without dementia speak up for those who have it, who can no longer recognise or articulate what they need. They may no longer be able to articulate their needs, or explain the reasons for their anxiety or distress, but the anxiety and distress is no less real for that – and all the more heartbreaking to witness.

A good place to start is in collectively facing up to the fact that it is in our midst and that each year hundreds of thousands of men and women are living with it and dying with it. If not you, someone very near you. If not now, soon.

Support, Information, Advice

If dementia is now a part of your life, there are places you can go for support and advice. I’ve already mentioned John’s Campaign. I found the Alzheimer’s Association forum, Dementia Talking Point, very helpful on all sorts of practical issues, and often very reassuring.

Some books that I found both fascinating and useful. Several of them at some point made me laugh, and all of them without exception, at some point made me sob.

- Nicci Gerrard (founder of John’s Campaign) – What Dementia Teaches us about Love

- Andrea Gillies – Keeper: A Book about memory, identity, isolation, Wordsworth and cake… (Andrea Gillies took on the care of her mother-in-law, who was in the middle stages of Alzheimer’s disease. This is a journal interwoven with an investigation of how Alzheimer’s works)

- Emma Healey – Elizabeth is Missing (a wonderful novel, whose protagonist is a woman with dementia, who can’t always recognise her daughter, but knows that her friend Elizabeth is missing…)

- Robyn Hollingworth – My Mad Dad: The Diary of an Unravelling Mind

- Wendy Mitchell – Someone I used to Know (Wendy was diagnosed with early onset dementia some years ago, and writes a truly remarkable blog about her life with the disease. Her experience is very different to that of my mother in law. But it’s a rare and invaluable gift to hear someone explaining so clearly what it’s like have dementia, and a joy to hear of the rich life she can lead even now.)