Archive for category The City

This new Hades

Posted by cathannabel in Michel Butor, The City, W G Sebald on July 1, 2016

(This is an edited version of a talk given at the ‘Everywhere & Nowhere’ postgraduate symposium of the Landscape, Space & Place group at the University of Nottingham, on 20 June 2016)

It might seem odd to posit the city of Manchester as an imagined place. However, from the beginnings of its rapid growth in the early years of the Industrial Revolution, the real city was mythologised by the many from around these islands and beyond them who came to see the miracle or shock city of the age. Manchester in the Industrial Revolution became an archetype of both shock and wonder, awesome and awful at the same time. As it grew, with remarkable speed and with no discernible plan, it attracted comparisons both with the greatest of human and divine achievements, and with the works of the devil.

For Disraeli it was ‘as great a human exploit as Athens’, for Carlyle, ‘every whit as wonderful, as fearful, as unimaginable, as the oldest Salem or prophetic city’. Many accounts, alongside these exalted descriptions, acknowledge the dichotomy – for example this from the Chambers Edinburgh Journal of 1858:

Manchester streets may be irregular, and its trading inscriptions pretentious, its smoke may be dense and its mud ultra-muddy, but not any or all of these things can prevent the image of a great city rising before us as the very symbol of civilisation, foremost in the march of improvement, a grand incarnation of progress.

Alexis de Tocqueville too was able to recognise both extremes. In Manchester ‘the greatest stream of human industry flows out to fertilise the whole world. From this filthy sewer pure gold flows. Here humanity attains its most complete development, and its most brutish; here civilisation works its miracles, and civilized man is turned back almost into a savage.’

Overall though the majority came down on the ‘awful’ side of the divide. Even Mrs Gaskell, who was a local, described the impression of the men working in the factories as ‘demons’. For others it was ‘a Babel in brick’, a ‘revolting labyrinth’, and its river was ‘the Styx of this new Hades’.

There were particular aspects of Manchester that inspired these reactions. De Tocqueville said that:

Everything in the external appearance of the city attests the individual powers of man; nothing the directing power of society. At every turn, human liberty shows its capricious force.

Whereas some cities’ growth can be illustrated by an expanding grid, or like Paris by the addition of layer upon layer of suburbs, Manchester grew organically, cramming factories and workers’ housing into whatever space was available, without much consideration of the living conditions that would result, minor things such as sanitation, for example, and the outcomes were grim.

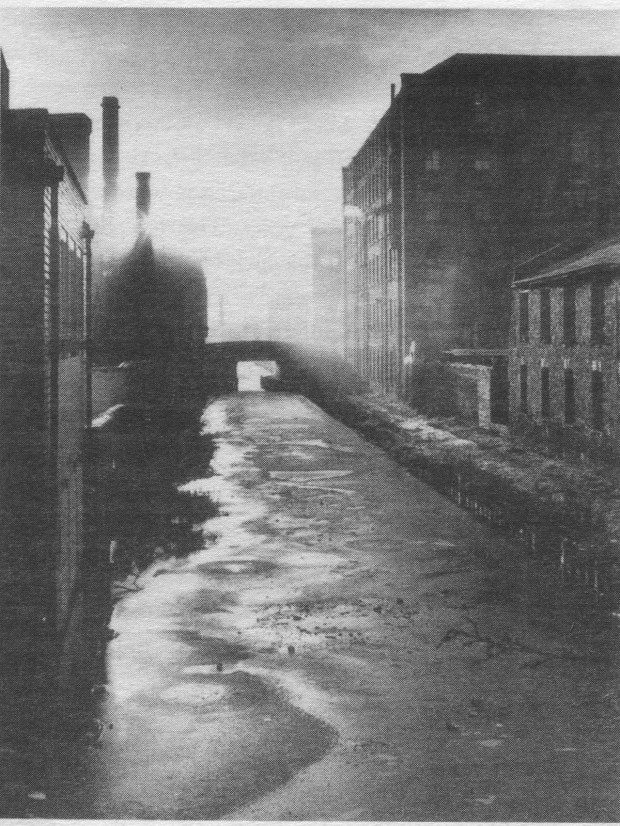

Manchester was thus characterised as ‘a vast unknowable chaos’, illustrated by the invocation of Erebus, in Greek mythology the personification of darkness, born of Chaos, who inhabits a place of darkness between Earth and Hades. So we have descriptions of chimneys ‘belching forth clouds of Erebean darkness and dirt, as if they had a dispensation from the devil’.

Hippolyte Taine records that ‘in the city’s main hotel, the gas had to be lit for five days: at midday one could not see clearly enough to write.’ The darkness was noted well into the 1950s. There were two factors here, not only the constant smoke from the chimneys but the moist air and relatively flat terrain, which meant that ‘the acid and other impurities become dissolved in the moisture, and the black parts of the smoke become wet and heavy’. This combination created the ‘terrifying Manchester fogs … when the phenomenon of temperature-inversion produced near darkness and zero visibility around the clock for days on end’.

The pollution had other effects. Sir James Crichton Browne (1902) rather marvellously described how ‘A sable incubus embarrasses your breathing, a hideous scum settles on your skin and clothes, a swart awning offends your vision, [and] a sullen cloud oppresses your spirits’.

There is a kind of trope of ‘first view of Manchester’ which strengthens the sense of an archetype, a mythical place. For example:

Alexis de Tocqueville – Voyages en Angleterre, Irlande, Suisse et Algerie (1835): A sort of black smoke covers the city. The sun seen through it is a disc without rays. Under this half daylight, 300000 human beings are ceaselessly at work. A thousand noises disturb this damp, dark, labyrinth.

Hugh Miller – First Impressions of England and its People (1847): One receives one’s first intimation of its existence from the lurid gloom that overhangs it. There is a murky blot in one section of the sky which broadens and heightens as we approach, until at length it seems spread over half the firmament. And now the innumerable chimneys come in view, tall and dim in the dun haze, each bearing atop its own troubled pennon of darkness.

Mrs Gaskell – North & South (1855): For several miles before they reached Milton, they saw a deep, lead-coloured cloud hanging over the horizon in the direction in which it lay.

Hippolyte Taine – Notes sur l’Angleterre (1874): We approach Manchester. In the copper sky of the sunset, a strangely shaped cloud hangs over the plain; beneath this immobile cover, the high chimneys, like obelisks, bristle in their hundreds; one can distinguish an enormous dark mass, the vague rows of buildings, and we enter the Babel of brick.

W G Sebald, The Emigrants (1992)

Max Ferber’s arrival in 1945: From a last bluff he had had a bird’s eye view of the city spread out before him … Over the flatland to the west, a curiously shaped cloud extended to the horizon, and the last rays of sunlight were blazing past its edges, and for a while lit up the entire panorama as if by firelight or Bengal flares. Not until this illumination died … did his eye roam, taking in the crammed and interlinked rows of houses, the textile mills and dying works, the gasometers, chemical plants and factories of every kind, as far as what he took to be the centre of the city, where all seemed one solid mass of utter blackness, bereft of any further distinguishing features.

The narrator’s arrival in 1966: By now, we should have been able to make out the sprawling mass of Manchester, yet one could see nothing but a faint glimmer, as if from a fire almost suffocated in ash. A blanket of fog that had risen out of the marshy plains that reached as far as the Irish Sea had covered the city, a city that spread across a thousand square kilometres, built of countless bricks and inhabited by millions of souls, dead and alive.

What strikes the observer in each case is that where they should be able to see the city, instead they see a pall of black smoke, a ‘murky blot’ in one part of the sky, a strangely shaped cloud that hangs over it. Coming closer they see the chimneys, each with its ‘troubled pennon of darkness’ and closer still the mass of buildings, the black river, the sombre brickwork. It’s also worth noting the striking similarity between Sebald’s description of Max Ferber’s first view of the city, and Hippolyte Taine’s.

Another feature attributed to Manchester which led to associations with hell or at least a cursed place was the absence of native flora and fauna. Birdlife was largely absent at the height of industrial activity, and much restricted later, until the Clean Air act created a more hospitable environment. And attempts to create parks, to give the inhabitants a taste of the countryside were doomed as trees and shrubs and blooms were poisoned by the fumes.

These conditions were not unique to Manchester. The industrial cities of the North East inspired John Martin’s apocalyptic paintings, and those of the Black Country Tolkien’s vision of Mordor.

And there’s an intriguing apocalyptic story published in the Idler magazine in 1893 about the doom of London, resulting from a seven day fog, with no wind to clear it, suffocating all of the inhabitants. But Manchester seemed to exert a particular fascination – the scale and the extremity of the conditions in the city drew visitors from across the country and from Europe. As Tristram Hunt says, in his study of the Victorian city, ‘in Manchester it was always worse’.

By the 1950s some of the most notorious slums had disappeared, and proper sanitation had long since removed the threat of cholera and typhus. But the fogs were still extreme, the air still heavy with smoke and metallic tasting vapours, the rain still a near-constant. In addition to the effects of pollution, there were areas of wasteland, bomb sites from the war, not yet redeveloped.

Michel Butor’s novel L’Emploi du temps, published 60 years ago, transformed Manchester into Bleston, and used its mythology to imbue its rain-drenched streets with a sense of dread and danger. Taking elements of the real city he subverts its mundane reality so that Manchester becomes Babel, Babylon, Daedalus’ labyrinth, a Circe or a Hydra. It also becomes Paris under Nazi occupation.

Michel Butor arrived in Manchester in 1951, straight from a spell teaching in Egypt. He was, as he described it, inundated with sun, and then plunged into Mancunian darkness. It was a climatic shock, and the very features of the city which had inspired earlier writers to flights of heightened prose and invocations of hell were to influence his response.

Darkness, fog, mud and soot, rain. These elements feature on almost every page of his novel, L’Emploi du temps (Passing Time), in which the city is renamed Bleston. So far, so realistic. But from very early on they begin to be associated with something beyond the combination of natural and manmade phenomena which Butor was observing.

The fog makes it difficult to find one’s way in the city – masking its shape so that the unwary find themselves going in circles, losing all sense of direction. It stifles, engulfs and sedates, oppressing the spirits. Bleston/Manchester, is a labyrinth, eluding navigation, confounding any attempt to grasp its totality, the narrator, Jacques Revel, says that ‘it grows and alters even while I explore it’. As in Andre Gide’s version of the Cretan labyrinth in his novel Thésée, the ‘narcotic fumes’ sap the will so that those within the labyrinth lose the desire to escape, forget that escape is even possible. On the walls near Bleston’s station, posters illustrate holiday destinations, but the narrator comments sardonically ‘as if it was really possible to get away’. His one attempt to get to countryside is doomed – the best the city can offer, it seems, is some nice parks. Thus the city is a prison, as it was effectively for so many of its past inhabitants.

Butor commented that ‘it is easy to see how the French capital hides beneath the mask of Bleston’. On the face of it, it’s far from easy. Paris is the city of light, a cosmopolitan centre of culture – Bleston/Manchester is characterised by darkness, dirt and narrowness of vision (literally and metaphorically). But something in the constant smell of smoke in the air, the darkness of evening when everything was closed, the way the inhabitants hunched their shoulders against the rain and scurried home ‘as if there were only a few minutes left before some rigid curfew’ triggered memories for Butor of a very different Paris.

Those who fled Paris in 1940 and then returned after the armistice found it uncanny, familiar yet profoundly different. There was a curfew, the clocks had been changed so that it got dark an hour earlier, and a pall of smoke hung over the city from the burning of tanks of oil as the German army advanced, which poisoned the air and drove its birdlife away.

This was the Paris of Butor’s adolescence. He lived near the Hotel Lutetia, HQ of the Abwehr (and after Liberation, the meeting point for returning deportees), near the prison du Cherche Midi where many resistance members were imprisoned, and he walked to school through streets where now plaques commemorate those who were killed during the Occupation and the liberation of the city. At his school both pupils and staff disappeared, some deported or imprisoned, some choosing a clandestine life in the Resistance. Butor described the sense that nothing was happening but that this nothing was bloody. The carceral menace of everyday life, as Debarati Sanyal put it.

Thus in Bleston the fog and the darkness are metaphorical as well as literal, creating not only confusion but fear. There is a constant sense of menace, and the city itself is the source. Personified as a sorcerer, as a Hydra, as both labyrinth and Minotaur, Bleston is at war with Revel, and he with it. But it’s also at war with itself, consuming itself in fire (prosaically a series of arson attacks on various premises encircling the city). The recurring motif of Cain and Abel is a reminder of the divisions between those who collaborated and those who resisted, as well as between occupier and occupied.

The novel is no allegory of the Occupation. This is one reading of a book that defies categorisation, a many-layered text. But my argument is that something in the extremity of Manchester, where it’s always worse, prompted memories of those dark years in Butor, and those memories created the tension in the novel, between the mundane events and the dark, violent interpretations of those events, between the humorous realism of the grim up north descriptions of rain and atrocious food and the sense of dread and danger on every page.

Around ten years after L’Emploi du temps was published, another young European, W G Sebald, arrived in the city, read Butor’s book, and began to write about his own Manchester, in The Emigrants and After Nature, transforming the landscape of industrial decay into a melancholic landscape of loss and trauma.

Like Butor, W G Sebald encountered a significant culture shock on arriving in Manchester, after teaching in Switzerland. Sebald was profoundly alienated from his home country of Germany. His sense of isolation ‘could not have been helped by his wanderings through scenes of slum clearance and urban decay.’

Objectively those areas were disappearing so one might surmise that Sebald sought them out, was drawn to their melancholy which reflected and intensified his own. It’s true that the Manchester Development Plan approved in 1961 (although not fully implemented, as I’ll mention later), and the implementation of smokeless zones were making significant improvements in the atmosphere and cleanliness of the city, even if children growing up in the city in the 60s still had plenty of bombsites to play on. However, Sebald’s ‘melancholy at alienation, and exile in a strange land’ found its correlative in the ‘desolate leftovers of nineteenth century Manchester’. It is also suggested that Sebald’s reading of L’Emploi du temps enhanced his melancholy but again it is likely that he was drawn to the novel because it resonated with his own mood and response to Manchester.

Thus the picture painted in The Emigrants of Manchester as ‘a city of ruins, dust, deserted streets, blocked canals, a city in terminal decline’ is probably a distortion. However, the narrative is only in part about the Manchester that Sebald encountered in 1966-7. ‘Manchester … fades into insignificance in relation to another important geographical, phantasmic and persistent presence, which is Germany’.

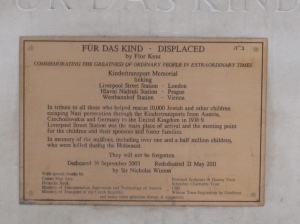

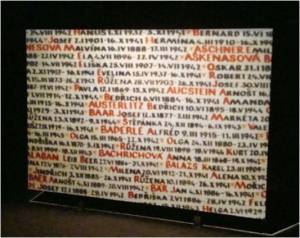

Sebald gives us more than one Manchester. We see the city first of all through the eyes of the narrator (who both is and isn’t Sebald) arriving in the 1960s, and then through the eyes of the titular Emigrant, Max Ferber, who arrives in 1945, having been sent on the Kindertransport in 1938 from Munich, and finally the narrator’s return in the 1990s, finding that a further cycle of improvement and decay has taken place in the interim.

For Ferber, Manchester triggers memories of Germany. This is partly due to its immigrant communities, the Jewish quarters with their names evoking a European past. But as Thomas Mann, exiled in the US, said, ‘Where I am, is Germany’. There’s another connotation. Manchester’s ‘night and fog’, its fire buried in ash, its chimneys, evoke a past that he escaped, thanks to his parents’ foresight, but which they did not.

Ernestine Schlant describes this aspect of Sebald’s writing as ‘“dense” time – a time in which past and present intersect, commingle, and overlap. This commingling destroys sequence and evokes the sense of a labyrinth with no exit‘. She was speaking specifically of Sebald’s writing, but it would equally be a powerful description of Butor’s novel, where Bleston’s past as Roman temple of war, divided Reformation city and industrial machine are threaded with Butor’s memories of Paris at war.

A brief postscript – I mentioned the Manchester Development Plan, published in 1961. This as it turns out is another imaginary Manchester – not drawing upon the myths of the past but upon a vision of the future.

Plans were drawn up in 1945, but budgetary constraints and building regulations meant that they were largely put on hold. By the time they were revisited, technological advances had opened up hitherto unimaginable possibilities for the city, with moving pavements, heliports and monorails. Once again, the economic climate changed before the plans could be realised and they stand now as a memorial to that other unrealised Manchester.

So in this very real city we can glimpse Engels’ hell on earth, Butor’s city at war, Sebald’s post-Holocaust landscape, the idealistic vision of the 1960s planners. The features that made Manchester the shock city of the 19th century are no longer readily visible. Manchester now is arguably just one of our major cities, unlikely to inspire comparisons with Athens or with Hades. But the past in all its various forms, as well as the unrealised visions of the future are there to be stumbled over, bubbling up between the paving stones. Unmemorialised, their presence is still felt.

Bibliography

Michel Butor, L’Emploi du temps (Minuit, 1956); English translation (by Jean Stewart), Passing Time (Faber, 1965)

W G Sebald, Die Ausgewanderten (Fischer, 1992); English translation (by Michael Hulse), The Emigrants (Vintage, 2002)

__, Nach der Natur (Fischer, 1995); English translation (by Michael Hamburger), After Nature (Hamish Hamilton, 2002)

Robert Barr, The Doom of London, The Idler (1893)

Charles Dickens, Hard Times (1854)

Benjamin Disraeli, Coningsby (1844)

Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England (1840)

Leon Faucher, Manchester in 1844

Elizabeth Gaskell, Mary Barton (1848), North and South (1855)

Andre Gide, Thésée (1946)

James Phillips Kay, The Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Classes Employed in the Cotton Manufacture in Manchester (1832)

Hugh Miller, First Impressions of England and its People (1869)

Hippolyte Taine, Notes sur l’Angleterre (1874)

Alexis de Tocqueville, Voyages en Angleterre, Irlande, Suisse et Algérie (1835)

Asa Briggs, Victorian Cities (Penguin, 1990)

Mireille Calle-Gruber, La Ville dans L’Emploi du temps de Michel Butor (Nizet, 1995)

Jo Catling and Richard Hibbitt (eds), Saturn’s Moons: W G Sebald – a Handbook (Legenda, 2011)

Mark Crinson, Urban Memory (Routledge, 2005)

J B Howitt, Michel Butor and Manchester, Nottingham French Studies, 12, 2 (1973)

Tristram Hunt, Building Jerusalem: The Rise and Fall of the Victorian City (Phoenix, 2005)

Michael Kennedy, Portrait of Manchester (Hale, 1970)

Alan J Kidd, Manchester (Keele UP, 1996)

Gary S Messinger, Manchester in the Victorian Age (MUP, 1985)

Stephen Mosley, The Chimney of the World (Routledge, 2008)

Terry Pitts, La Catastrophe muette: Sebald à Manchester, Ligeia, 105-8 (2011)

Peter Preston and Paul Simpson-Housley (eds), Writing the City: Eden, Babylon and the New Jerusalem (Routledge, 1994)

Natalie Rudd, Fabrications : New Art and Urban Memory in Manchester (UMiM, 2002)

Debarati Sanyal, The French War, in Cambridge Companion to the Literature of WWII (CUP, 2009)

Ernestine Schlant, The Language of Silence (Routledge, 1999)

Janet Wolff, Max Ferber and the Persistence of Pre-Memory in Mancunian Exile, Melilah, 2 (2012)

Mad Travellers

Posted by cathannabel in Literature, Michel Butor, Refugees, The City, W G Sebald on July 4, 2015

(adapted from a paper given at ‘There & Back Again’, a postgraduate conference at the University of Nottingham, organised by the Landscape, Space, Place Research Group. The title is taken from Iain Hacking’s fascinating study of the fugueur phenomenon)

The idea of wandering, of travelling without constraints, without a humdrum practical purpose, is perennially appealing to most of us, even if, for most of us, the drawbacks come to mind pretty speedily if we start to entertain the notion. Some do it anyway – seize the moment when the obstacles are not insuperable – but generally it’s something to enjoy vicariously, or to indulge in short bursts, taking time out of a holiday schedule to just have a stroll around foreign streets.

Throughout myth and literature there are many wanderers who cross seas, continents and centuries. For some it’s a pastime, a means of avoiding commitments or encumbrance:

I’m the type of guy that likes to roam around

I’m never in one place, I roam from town to town

And when I find myself fallin’ for some girl

I hop right into that car of mine and ride around the world (Dion, The Wanderer, 1961)

Everyday in the week I’m in a different city

If I stay too long people try to pull me down

Hendrix suggests that the prejudices of the cities in which he finds himself push him to leave, as well as, like Dion, that if he does sometimes feel his heart ‘kinda gettin’ hot’ for some woman, he moves on before he gets caught. For some, wandering is a subversive practice (not using the city streets in the prescribed way), for others it’s a compulsion, even a curse.

The flâneur is one of those archetypal wanderers. This classic definition is by Baudelaire, writing in 1863 in his ‘Le Peintre de la vie moderne’.

The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world—impartial natures which the tongue can but clumsily define. The spectator is a prince who everywhere rejoices in his incognito. The lover of life makes the whole world his family, just like the lover of the fair sex who builds up his family from all the beautiful women that he has ever found, or that are or are not—to be found; or the lover of pictures who lives in a magical society of dreams painted on canvas. Thus the lover of universal life enters into the crowd as though it were an immense reservoir of electrical energy. Or we might liken him to a mirror as vast as the crowd itself; or to a kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness, responding to each one of its movements and reproducing the multiplicity of life and the flickering grace of all the elements of life.

He – and I use the masculine pronoun entirely deliberately – is ‘observateur, flâneur, philosophe, appelez-le comme vous voudrez’.

He – and I use the masculine pronoun entirely deliberately – is ‘observateur, flâneur, philosophe, appelez-le comme vous voudrez’.

He is a perfect stroller, a passionate spectator, an erudite wanderer. He walks the streets, probably alone, with no map or itinerary, with the confidence that comes from being male, well-educated and wealthy. His milieu is the city, and quintessentially Paris. One might think that the boulevards and arcades of Haussmann’s Paris lent themselves to strolling so much better than the labyrinthine streets of the old city, but it was that old city that defined the flâneur, allowing (in Edmund White’s words) ‘a passive surrender to the aleatory flux of the innumerable and surprising streets’.

The flâneur is a prototype detective, his apparent indolence masking intense watchfulness. This recalls Edgar Allen Poe’s story, ‘The Man of the Crowd’ (which was translated by Baudelaire), in which a man recovering from illness sits in a London coffee shop, watching the passers-by, and engaging in Holmesian deductions about their occupation and character. His attention is drawn by an old man who he is unable to read, and he feels compelled by insatiable curiosity to follow him, for a night and a day, as the man moves unceasingly through the city: he is the man of the crowd – not only hiding within it, but unable to exist outside it.

Walter Benjamin in his 1935 study of Baudelaire suggests that Baudelaire identifies the old man as a flâneur. This must be a misreading on Benjamin’s part, since the old man is as manic as the flâneur is composed. The flâneur may ‘set up house’ in the heart of the crowd, becoming part of ‘the ebb and flow of movement’, but he remains separate, above the mass. He is, like Baudelaire and Benjamin, at the same time engaged with and alienated by the city.

Poe’s story does give us a flâneur, however, in the person of the narrator, who can and does choose to abandon his pursuit, stepping aside to resume his life, and a different kind of wanderer, in the person of the man of the crowd. Steven Fink argues persuasively that the man of the crowd is the mythological figure of the Wandering Jew, condemned to wander endlessly as punishment for a terrible crime. (He has a number of counterparts, including, amongst others, Cain, the Flying Dutchman, and the Ancient Mariner.) Certainly this description by Benjamin’s contemporary, Siegfried Krakauer, is remarkably close to Poe’s description of the old man:

‘there arose confusedly and paradoxically within my mind, the ideas of vast mental power, of caution, of penuriousness, of avarice, of coolness, of malice, of bloodthirstiness, of triumph, of merriment, of excessive terror, of intense – of supreme despair … How wild a history … is written within that bosom!’. (Edgar Allen Poe, ‘The Man of the Crowd’)

Imagine [his face] to be many faces, each reflecting one of the periods which he traversed and all of them combining into ever new patterns as he restlessly and vainly tries on his wanderings to reconstruct out of the times that shaped him the one time he is doomed to incarnate. It is a terrible face, ‘assembled from the many faces of the dead’. (Siegfried Krakauer – History, the Last Things Before the Last (OUP, 1969))

If the man of the crowd is no flâneur, he does bear a stronger resemblance to the fugueur, a lesser-known (and shorter-lived) phenomenon which emerged in the 1880s. Bordeaux medical student Philippe Tissié and neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris documented a number of cases of men undertaking strange and unexpected trips, in states of obscured consciousness.  They were subject to hallucinations, and often dominated by ideas of persecution. Their conduct during the episode appeared normal, but they were unconscious of what they were doing, and had no memory of it afterwards – in a state of dissociative fugue. A fugue state is defined as involving selective memory loss, the inability to recall specific – perhaps traumatic – events. This may be accompanied by wandering and travelling, in an attempt to recover memory/identity, or perhaps in a flight from it – the etymological paradox of flight/pursuit.

They were subject to hallucinations, and often dominated by ideas of persecution. Their conduct during the episode appeared normal, but they were unconscious of what they were doing, and had no memory of it afterwards – in a state of dissociative fugue. A fugue state is defined as involving selective memory loss, the inability to recall specific – perhaps traumatic – events. This may be accompanied by wandering and travelling, in an attempt to recover memory/identity, or perhaps in a flight from it – the etymological paradox of flight/pursuit.

The fugueur is quite distinct from the flâneur whose journeying is deliberately aimless and random, an end in itself. His itinerary may defy linear logic but nonetheless is purposeful, even if that purpose can be discovered only retrospectively. The flâneur, in his fine clothes, walked the streets as if he owned them because, wealthy and well-educated, he could. The fugueur, in his state of obscured consciousness, was likely to be mistaken, instead, for a vagrant. Albert Dadas, ‘patient zero’ in the mini-epidemic of ‘mad travelling’, was repeatedly arrested for vagabondage. The fugueurs were generally of more modest means than the flâneurs – tradesmen, craftsmen or clerks – and their travels took them much further afield.  If someone spoke of a city or a country Albert was seized by the need to go there, and did so, often then finding himself in difficulties due to lack of funds.

If someone spoke of a city or a country Albert was seized by the need to go there, and did so, often then finding himself in difficulties due to lack of funds.

One of Charcot’s patients was a young Hungarian Jew named Klein, who was ‘constantly driven by an irresistible need to change his surroundings, to travel, without being able to settle down anywhere’. This particular patient prompted a link with the then prevailing view that Jews were more prone than other races to various forms of neurasthenia and that this particular manifestation was ‘in the character of their race’. Thus the Wandering Jew was, according to Henri Meige’s thesis, ‘only a sort of prototype of neurotic Israelites journeying throughout the world’. Even at the time it was pointed out, fairly acerbically, that if the Jews had a tendency to move from place to place, this was in generally externally rather than internally driven, as persecution and prejudice made it necessary to leave one home in search of another.

Charcot’s diagnosis, and his use of the term ‘hystero-epilepsy’ in particular, fell out of favour, largely due to the failure to identify a common cause that would account for a collection of rather disparate individual cases. In the twentieth century the two types of wanderer seem often to merge, as trauma and exile create a more melancholy and more driven wanderer. One can trace a line from Baudelaire’s flâneur to the Surrealists, via Walter Benjamin’s description of flânerie as a dream state in which ‘The city as a mnemonic for the lonely walker [: it] conjures up more than his childhood and youth, more than its own history’, to Guy Debord’s dérive as subversive practice, and on to today’s psychogeographers. Rather than being a disaffected and detached observer, the flâneur in the late 20th and 21st century may be in flight from memory, from identity, at home nowhere, an exile who feels no connection, or only a highly problematic one, to homeland or origins.

Michel Butor’s 1956 novel, L’Emploi du temps is set in a northern English industrial city, called Bleston but clearly inspired by Manchester, where Butor had worked a few years earlier. It takes the form of a diary kept by his protagonist, Jacques Revel, in the city for a one-year placement. We know nothing of Revel’s life before his arrival in Bleston, or of what he will do after he leaves. He speaks of his year there as a prison sentence – he is unable to leave the city during that period, and compelled to leave it on a specific date. He is certainly not at home in Bleston, but he seems entirely rootless, without any connection elsewhere. In his restless wanderings through the streets, he seems to be searching – mostly fruitlessly – for lodgings, for someone whose name he does not know who he met on an earlier walk, for the elusive countryside. But ultimately his quest is to master the city by walking its streets, grasping the reality which seems to be changing around him as he walks – it is a phantasmagorical city, whose heavily polluted atmosphere creates a narcotic dream-like state, distorting his perceptions and leaving him disorientated.

Butor’s novel had a significant influence on W G Sebald, who came to Manchester about 15 years later. Sebald read L’Emploi du temps when he first arrived, and it inspired a poem, ‘Bleston: A Mancunian Cantical’, as well as having a wider impact on his work.

In Sebald’s novels, the narrator (who may or may not be, to some extent, Sebald) invariably begins by describing a journey. He is precise about when, and where, although the layering of timeframes and locations means that we can lose these certainties as the narrative progresses, but frequently the ‘why’ is obscure, not just to the reader but to the narrator himself. The narrator and the various protagonists are rarely, if ever, ‘at home’. They are often in transit or in provisional, interim spaces such as waiting rooms, railway stations, and transport cafes. Their journeys often induce episodes of near paralysis, physical or mental, and they end inconclusively, often with a sense that the quest will continue after the final page.

But if the Sebaldian narrator is a contemporary example of the melancholy flâneur, Jacques Austerlitz connects us directly with the fugueur, and with wandering as a response to trauma and loss. As a child, Austerlitz arrived in England on the Kindertransport, where his foster parents gave him a new life, and a new name, telling him nothing of his past, or the fate of his parents, until, as a sixth former, he learns that he is not Dafydd Elias.

For many years he avoids any topic or image which might shed light on or raise questions about his origins. But, increasingly isolated, and with his life ‘clouded by unrelieved despair’, tormented by insomnia, he undertakes nocturnal wanderings through London, alone, outwards into the suburbs, and then back at dawn with the commuters into the city. These excursions begin to trigger hallucinations, visions from the past, for example, the impression that ‘the noises of the city were dying down around me and the traffic was flowing silently down the street, or as if someone had plucked me by the sleeve. And I would hear people behind my back speaking in a foreign tongue …’. He is irresistibly drawn to Liverpool Street Station, a place full of ghosts, built as it is on the remains of Bedlam hospital, and, in the disused Ladies’ Waiting Room, encounters the ghosts of his foster parents and the small boy he once was.

Thus his obsessive wanderings appear to have had a sub-conscious purpose, taking him back to the point of rupture between one life and another. He embarks upon a new phase of wandering, driven by the need to find his home and his parents. Overhearing a radio documentary about the Kindertransport, and the reference to a ship named The Prague, like Albert Dadas, the original fugueur: ‘the mere mention of the city’s name in the present context was enough to convince me that I would have to go there’.

Austerlitz’s quest remains incomplete at the end of the novel. In the course of his wanderings he has, he believes, discovered his former home in Prague and traced his mother to Teresienstadt and his father to the Gurs concentration camp in France in 1942. Beyond that he knows only that his mother ‘was sent east’ in 1944. He does not know where, when, or even whether they died.

His quest, and his confrontation with the losses that defined his life, leads to ‘several fainting fits … temporary but complete loss of memory, a condition described in psychiatric textbooks … as hysterical epilepsy’. He is taken, significantly, to the Salpêtrière, where Charcot established this diagnosis almost a century earlier. This diagnosis would only be included in psychiatric textbooks as a historical footnote – an example of Sebald’s dense or layered time – we know precisely where we are, but the ‘when’ is not so straightforward.

Thus we’ve come full circle. And I want to make another tentative, perhaps fanciful connection. Sebald invites us to make all sorts of links with the name Austerlitz – the battle, the Parisian railway station, even Fred Astaire. And there’s always the echo of another name, the likely final destination of both of his parents, unspoken here except in a reference to the Auschowitz Springs near Marienbad. One more then – Ahasuerus, the name often given to the mythological Wandering Jew.

Baudelaire’s description of the flâneur – ‘être hors de chez soi, et pourtant se sentir partout chez soi (away from home and yet at home everywhere)’ has echoed through the twentieth century and into our own, accumulating more and more melancholy baggage. That this phrase has darker undertones than Baudelaire will have intended is brought home by a speech made by Hitler in 1933, in which he described the Jewish people, the ‘small, rootless international clique’, as ‘the people who are at home both nowhere and everywhere’.

In our time then, rather than someone at ease wherever he finds himself, we are likely to think of the refugee and the exile, adapting without putting down roots, unable to return but unable fully to belong, always sub-consciously ready to move on or even keeping a bag permanently packed, just in case. For the original flâneur this characteristic was an affectation, a chosen detachment and rootlessness. For the fugueur, driven by trauma or crisis of identity, it is a curse, to have to wander, and never to find answers, or find home.

Anderson, George K, The Legend of the Wandering Jew (Hanover/London: Brown UP, 1991)

Benjamin, Walter, ed. Michael W Jennings, The Writer of Modern Life: Essays on Charles Baudelaire (Cambridge, MA/London: Belknap Press of Harvard UP, 2006)

Brunel, Pierre (ed), translated by Wendy Allatson et al, Companion to Literary Myths, Heroes and Archetypes (NY/London: Routledge, 1996)

Coverley, Merlin, Psychogeography (Harpenden: Pocket Essentials, 2006)

Fink, Steven, ‘Who is Poe’s Man of the Crowd?’, Poe Studies, 44, 2011 (17-38)

Gilloch, Graeme, Myth and Metropolis: Walter Benjamin and the City (Cam.: Polity, 1996)

Goldstein, Jan, ‘The Wandering Jew and the Problem of Psychiatric Anti-Semitism in Fin-de-Siècle France’, Journal of Contemporary History, 20, 4(October 1985), 521-52

Hacking, Ian, ‘Automatisme Ambulatoire: Fugue, Hysteria and Gender at the Turn of the Century’, Modernism/Modernity, 32 (1996), 31-43

__, ‘Les Alienés voyageurs: How Fugue Became a Medical Entity, History of Psychiatry, 7, 3 (September 1996), 425-49

__, Mad Travellers: Reflections on the Reality of Transient Mental Illnesses (Free Association Books, 1998)

Kuo, Michelle and Albert Wu, ‘Imperfect Strollers: Teju Cole, Ben Lerner, W G Sebald and the Alienated Cosmopolitan’, Los Angeles Review of Books, 2 February 2013

Lauster, Martina, ‘Walter Benjamin’s Myth of the Flâneur’, Modern Language Review, 102, 1 (January 2007), 139-56

McDonough, Tom, ‘The Crimes of the Flâneur’, October, 102 (2002), 101-22

Micale, Mark S, In the Mind of Modernism: Medicine, Psychology and the Cultural Arts in Europe and American, 1880-1940 (Stanford UP, 2004)

Seal, Bobby, ‘Baudelaire, Benjamin and the Birth of the Flâneur’, Psychogeographic Review, 14 November 2013

White, Edmund, The Flaneur: A Stroll through the Paradoxes of Paris (Bloomsbury, 2008)

www.artslant.com/la/articles/show/42145

http://www.thelemming.com/lemming/dissertation-web/home/flaneur.html

http://www.othervoices.org/1.1/gpeaker/Flaneur.php

http://imaginarymuseum.org/LPG/debordpsychogeo.jpg

http://www.paris-art.com/agenda-culturel-paris/Le%20Premier%20fugueur/Furaker-Johan/11840.html

http://www.karenstuke.de/?page_id=1192

https://dianajhale.wordpress.com/2013/11/01/tracing-sebald-and-austerlitz-in-londons-east-end/

Furnace Park // an introduction on the cusp of an opening

Posted by cathannabel in The City, Visual Art on August 16, 2013

Reblogged from Occursus – Amanda Crawley Jackson’s account of the Furnace Park project.

In summer 2012, occursus – a loose collective of artists, writers, researchers and students that coalesced around a weekly reading group I had set up with Laurence Piercy from the School of English at the University of Sheffield – organised a series of Sunday-morning walks along unplanned routes in Shalesmoor, Kelham Island and Neepsend. As we looped through the chaotic mix of derelict Victorian works, flat-pack-quick-build apartment blocks, converted factories and student residences, sharing stories and sometimes, quite simply, wondering what on earth we were doing there, without umbrellas, in the rain, we came across the acre and a half of brownfield scrubland we’ve named Furnace Park. In collaboration with Matt Cheeseman (from the University of Sheffield’s School of English), Nathan Adams (a research scientist working in the Hunter Laboratory at the University of Sheffield), Ivan Rabodzeenko and Katja Porohina (founders of SKINN – the Shalesmoor, Kelham Island and Neepsend…

View original post 1,859 more words

From contribution to collaboration: Refugee Week and the value of seeing like a city

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees, The City on June 17, 2013

A fascinating and challenging contribution to Refugee Week – from cities@manchester

by Jonathan Darling, Geography, University of Manchester

Today sees the start of Refugee Week 2013, an annual celebration of the contribution of refugees to the UK that seeks to promote better understanding of why people seek sanctuary. Refugee Week has been held annually since 1998 as a response to negative perceptions of refugees and asylum seekers and hostile media coverage of asylum in particular (Refugee Week 2013). Refugee Week promotes a series of events across the UK, from football tournaments and theatre productions to exhibitions and film screenings, all designed to promote understanding between different communities.

Whilst Refugee Week is a national event it finds expression in local activities organised in a range of cities. In part, this is in response to the dispersal of asylum seekers across the UK, meaning that refugees and asylum seekers have been increasing visible in a range of towns and cities over the…

View original post 2,345 more words

The rebuilding of Paris and its reflection in works by Zola, Verne and Hugo

Posted by cathannabel in Literature, The City on April 27, 2013

Décombres de l’avenir et projets rudéraux : les métamorphoses de Paris chez Verne, Hugo et Zola

Claudia Bouliane’s recently published MA dissertation is available online as a PDF.

The abstract is as follows :

Between 1853 and 1870, many areas of the French capital are torn down to allow the establishment of new avenues by Baron Haussmann, Paris’ prefect under Napoleon III. These major urban projects have struck the social imaginary and became an object of fascination for literature. This essay is located on the grounds of sociocriticism and seeks to understand how Verne’s, Hugo’s and Zola’s texts interpret the Paris’ new urban conformation. In Paris au XXe siècle (1863) Jules Verne is planning future destructions and, in turn, imagines the strange constructiveness of residual past. Although in exile, Victor Hugo is very aware of urban and social changes under way. In Paris (1867) his writing works to make compatible…

View original post 94 more words

Michel BUTOR; l’espace entre 2 villes

Posted by cathannabel in Michel Butor, The City on April 25, 2013

Ajoutez votre grain de sel personnel… (facultatif)

LES LIGNES DU MONDE - géographie & littérature(s)

On n’est pas le même partout. L’équilibre entre 2 villes ; deux pôles ; et ce qui les relie : un fil de la vierge léger léger : le trajet en train. Il y a longtemps que cette vieille édition rose de 1994 (achetée sur conseil : “tu aimes le train, c’est un roman à lire dans le train, d’autant que tu prends souvent cette ligne” (fut un temps avec arrêt à Firenze, ville non mentionnée il me semble dans le roman)) passe d’étagère en étagère. Donc près de 20 ans après – laissé mûrir le livre, commencé une fois à l’époque, prêté plusieurs fois depuis – la litanie des gares, l’aller pour Rome.

car s’il est maintenant certain que vous n’aimez véritablement Cécile que dans la mesure où elle est pour vous le visage de Rome, sa voix et son invitation, que vous ne l’aimez pas sans Rome et…

View original post 440 more words

The Original Modern

Posted by cathannabel in Michel Butor, The City, W G Sebald on April 3, 2013

cities@manchester on Manchester, the original shock city

by Brian Rosa, PhD candidate in Geography

Manchester is a city of superlatives: it was the prototypical “shock city” of the Industrial Revolution, Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx’s model for everything that was abhorrent in the industrial capitalist city, and one of the birthplaces of the labor and women’s suffrage movements. In its heyday, Manchester was depicted in literature of Engels, Alexis de Toqueville and later the paintings of L.S. Lowry, as an uninterrupted, chaotic anti-landscape of chimneys and smoke, strewn across a featureless topography. Its unprecedented configuration invoked equal parts awe and dread, moral panic, and tempestuous visions of the future. In 1833, Toqueville described the crowded conditions, poorly constructed housing, hulking factories, and environmental degradation of Manchester: “From the foul drain the great stream of human industry flows out to fertilize the whole world. From this filthy sewer pure gold flows. Here humanity attains its most complete…

View original post 1,086 more words

Pierre Alechinsky et les plans de Paris

Posted by cathannabel in Michel Butor, The City, Visual Art on March 15, 2013

Alechinsky is one of many visual artists with whom Michel Butor has worked since the 1960s.

LES LIGNES DU MONDE - géographie & littérature(s)

Comme je me renseigne sur Alechinsky, sa vie son œuvre, je finis par trouver des dessins sur plans – de Paris (ça me revient : “tu sais Alechinsky, il a utilisé des cartes comme support, ça devrait t’intéresser”). Je sélectionne ici les arrondissements que je connais mieux.

L’arrondissement de ma naissance.

L’arrondissement du Lycée.

L’arrondissement de l’université.

Je trouve aussi ces impressions de Cherbourg. Petit résumé en 7 vignettes.

Butor and Sebald – brief further thoughts

Posted by cathannabel in Michel Butor, The City, W G Sebald on January 19, 2013

I’ve written previously about the relationship between Bleston and Manchester, and about the links between Butor and Sebald, and I’ve just been exploring the fascinating collection of essays on Sebald in Melilah, the Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies, alerted by Helen Finch’s recent blog about Sebald’s Manchester. It’s good to see the link with Butor explored a bit more, but I would have to take issue in some respects with Janet Wolff’s article, ‘Max Ferber and the Persistence of Pre-Memory in Mancunian Exile’, which I think fails to fully identify the deeper connections between the two writers.

I would agree that Passing Time is not about Manchester in a straightforward way but I think Wolff takes that too far when she says that ‘none of this is about an actual city’, and that Revel’s diatribes against Bleston are ‘the ravings of a neurasthenic, whose debilitated psychological state produces monsters in the environment’. (p. 52) This is not a new charge – reviewers have in the past diagnosed Revel with depression or schizophrenia. But I’d argue that rather than alerting us to an unreliable narrator, the mismatch reminds us that Bleston is not just Manchester, not just any particular city. It contains many cities, real and fantastical.

But it is based more upon Manchester in its physical reality than on any other city, and contrary to Wolff’s statement that ‘there are no physical descriptions at all (quite unlike the Manchester of ‘Max Ferber’)’, there are many descriptions of Manchester landmarks, as J B Howitt has shown (in his article ‘Michel Butor and Manchester’, even though Butor takes and uses those features which are relevant to him, and changes or ignores those that are not.

What interests me most, however, is Wolff’s argument that the Manchester of The Emigrants fades into insignificance in relation to ‘another geographical, phantasmic and persistent presence’.

My studies of Butor are concerned precisely with identifying that presence in Passing Time. More anon.

- Janet Wolff, ‘Max Ferber and the Persistence of Pre-Memory in Mancunian Exile’, in Melilah, 2012 Supplement 2, Memory, Traces and the Holocaust in the Writings of W.G. Sebald. (Guest editors: Jean-Marc Dreyfus and Janet Wolff)

- http://helenfinch.wordpress.com/2013/01/13/the-roman-road-under-the-casino-lost-manchester/

- J B Howitt, ‘Michel Butor and Manchester’, Nottm French Studies, 12 (1973), 74-85

Engaging with the city’s past

Posted by cathannabel in The City on April 3, 2012

A number of the discussions we’ve had about the city over the last two years have touched on how we engage with its past. We’ve discussed post-traumatic urbanism through the lens of Lebbeus Woods’ War and Architecture(see also the fascinating exhibition of Woods’ early drawings) and have also begun to think through our engagement with (or perhaps literal and/or conceptual avoidance of) recent sites of trauma in the city. We’ve walked around Kelham Island, considering the ways in which a city’s history becomes heritage, but also how certain narratives become dominant and survive, while others are minorised and erased.

Our current project engages with figures and movements from Sheffield’s past: Ebenezer Elliott, the Sheffield Socialist Society, Edward Carpenter, the Chartists… And we would like to invite people to contribute their thoughts, memories and expertise to an archive that will be accessible through our new interactive…

View original post 1,072 more words