Archive for January, 2016

Don’t Stand By

Posted by cathannabel in Genocide, Second World War on January 27, 2016

What makes someone give a damn when it’s not their turn to give a damn? Giving a damn when it’s not their job, or when it’s a stranger who needs help rather than a friend or a neighbour, someone to whom they owe nothing?

The website of Yad Vashem includes the names and many stories of those who have been designated ‘Righteous amongst the Nations’.

These are people who sheltered Jews or helped them to escape during the Holocaust, often taking huge risks themselves to do so.

Most rescuers started off as bystanders. In many cases this happened when they were confronted with the deportation or the killing of the Jews. Some had stood by in the early stages of persecution … but there was a point when they decided to act, a boundary they were not willing to cross.

Importantly, these are the people we know about. We know what they did because the people they helped to save told their stories. But there were many, many more whose stories have not been told. Many of those who survived the Holocaust have never talked about what they experienced, and those who were children at the time may not have known who did what, who took what risks to keep them safe. The rescuers themselves have often been silent about what they did – in parts of Eastern Europe it was hardly wise to make a noise about it after the war, and others were too modest to promote themselves as heroes. It is also worth noting that some of those who chose not to stand by were themselves murdered, and some had to endure the knowledge of the fate that befell those who they had tried to save – in either case it is likely that their acts are and will remain unknown.

Nicholas Winton did not, as is sometimes reported, keep entirely silent about his work in organising transports of children out of Czechoslovakia, but he certainly wasn’t well-known for it, and it took a television programme in 1988 to bring it to worldwide attention. He is not recorded amongst the Righteous – but only because he himself was of partly Jewish ancestry. He was scrupulous in recognising that the achievement was not his alone, and his reticence may also have in part been prompted by the painful knowledge that many more children could have been saved, had the US and other nations been willing to take more of them in.

As the number of survivors dwindles year on year, we may never know how many more of the Righteous there were.

In Poland, the epicentre of the Holocaust, over 6,500 people are recorded on Yad Vashem’s database. This is the largest number for any of the countries listed – all the more remarkable since in Poland alone the act of saving or trying to save a Jew was punishable by death for the rescuer and their family.

Stefan Szablewski may have been one of the unknown Righteous. His grandson, Marek, has spent the last few years trying to piece together a remarkable story of life in Warsaw, of survival and resistance. This has been a significant challenge:

I realised that not only did I have a unique tale to tell, but that as an only child I was the sole keeper. My knowledge, however, was incomplete. I needed to find the missing parts of the jigsaw puzzle to verify the facts that I had, and to learn more about the bigger picture. All I had to go on were my memories of conversations, several boxes of documents, a handful of photographs and medals, a bookshelf of books about Poland, a few contacts, and three precious tapes recorded for me by my father, which told some, but not all, of the story.

What these fragments show is that Stefan’s third wife, Anna, was Jewish and that she and her daughter were kept safe during the occupation of Warsaw, living under a false identity. In addition, there are records which state that ‘he organised safe houses or accommodation for people who were hiding along with the fabrication of identity papers, and also hid resistance literature and medical supplies.’ But there’s no hard evidence – just handwritten testimonies, and the recollections of Witold, Stefan’s son. Witold himself went into the Ghetto before its destruction, smuggling messages to the Jewish Council, and did what he could to help his stepmother’s family. Both the necessary habit of secrecy about such activities, and the level of destruction in Warsaw make it very difficult to find out more, or to know with certainty what happened. The efforts of a second or third generation now are to gather the fragments that do exist, and build as much of a story as possible. However incomplete, however many question marks remain, these stories are vital and compelling, and a reminder that the worst of times can bring out the best in people as well as the worst.

In Rwanda, the speed and intensity of the genocide meant that the kind of acts commemorated at Yad Vashem are even less likely to be recorded, and the narratives may be disputed. We have the account of Carl Wilkens, the only American who stayed in Rwanda, against all advice, and did what he could to protect the lives of Tutsi friends, and by talking his way through roadblocks and negotiating with senior army figures (people who were heavily implicated or actively involved in orchestrating the genocide) to get supplies through and then to arrange the safety of the children in an orphanage.

Of course, the story of Rwanda is the story of a world of bystanders, and those who did stay, and did what they could, are haunted, tormented by the lives they couldn’t save and the knowledge that had the US and other nations responded to the warnings and the increasingly desperate pleas from those who were witnessing the slaughter, so many more lives could have been saved. Whilst the targets of the killing were clearly Tutsi and Hutus suspected of helping them, the murder of Belgian peacekeepers early in the genocide meant that Wilkens and others could not be certain that they would be safe, and as the militia at the roadblocks were frequently drunk and out of control, there is no doubt that they took huge risks. Hutu Rwandans who hid friends, neighbours and colleagues rather than joining in the killing, or handing them over to the mobs, were however taking much greater risks, and if discovered they were certainly killed.

The ending of the film Shooting Dogs has always bothered me. The film shows a young Briton who was evacuated on a UN transport, leaving around 2,000 Tutsi in the compound of the Ecole Technique Officiel in Kigali, surrounded by Interahamwe militia, almost all of whom were killed as soon as the UN trucks left. In the final scenes, he is asked by a survivor why he left and he says that he left because he was afraid to die. This is disingenuous (and not challenged by the film) – everyone in that compound was afraid to die. He left because he could. Wilkens’ fellow Americans, and the majority of the Europeans in Rwanda when the genocide began, left because they could. They had a choice, and – for reasons that any of us can understand – they chose to take the escape route offered to them. Reading these stories, most of us will ask ourselves, would I have left when I could? Would I have stayed and tried to help? If I’d lived in Occupied Paris, or Warsaw, would I have kept my head down, or tried to help?

If you were a gendarme, or a civil servant, or even a Wehrmacht officer, you could do your job, as defined by the occupying forces, and compile lists of Jews to be rounded up, or round them up and transport them to transit camps, and then on to cattle trucks, or carry out the murders yourself. Or you could use that position to get a warning out about an impending round-up, or produce false papers to enable Jews to escape, or take direct action to get people to safety.

It came down, as it always does, to individuals, to their ability to empathise, to see not the vilified ‘Other’ but someone like themselves, and to their sense of what is fair and right. Fear can overwhelm both, but somehow, wherever and whenever the forces of hatred are unleashed, there will be some who will refuse to stand by.

Think of Lassana Bathily, a Malian Muslim who worked in the kosher supermarket in Paris which was attacked after the Charlie Hebdo massacre. He took some of the customers to the cold store to hide, whilst the killers shot and killed Jewish customers in the shop.

Think of Salah Farah. When al-Shabab attacked the bus he was travelling on in Mandera in Kenya, the attackers tried to separate Muslims and Christians. Passengers were offered safety if they identified themselves as Muslim. The response from many was to ask the attackers to kill all of them or leave all of them alone. Muslim women on the bus gave Christian women scarves to use as hijabs. Farah was one of those who refused the offer of safety, and he was shot. He died in hospital almost a month after the attack.

Think of Salah Farah. When al-Shabab attacked the bus he was travelling on in Mandera in Kenya, the attackers tried to separate Muslims and Christians. Passengers were offered safety if they identified themselves as Muslim. The response from many was to ask the attackers to kill all of them or leave all of them alone. Muslim women on the bus gave Christian women scarves to use as hijabs. Farah was one of those who refused the offer of safety, and he was shot. He died in hospital almost a month after the attack.

There are always some who refuse to stand by.

http://www.thefigtree.org/april11/040111wilkens.html

http://hmd.org.uk/resources/stories/hmd-2016-carl-and-teresa-wilkens

http://hmd.org.uk/resources/stories/hmd-2016-sir-nicholas-winton

http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/righteous/stories/sendler.asp

http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/righteous/stories/socha.asp

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-35352763

http://www.durhamcathedral.co.uk/news/marek-szablewski

At the Dark of the Moon – a poem by Katherine Inskip

Posted by cathannabel in Music on January 11, 2016

Amongst the many Bowie tributes which have appeared on my Facebook wall and Twitter feed (indeed, there has been little else today), there was this poem, by a friend and former colleague. I know Katherine Inskip as an astronomer and University teacher – I had no idea she was a poet. And this, written as an immediate response to the loss that we’ve all been feeling, is just so right. Thanks Katherine.

He died at the dark of the moon

and I cannot help but wonder

if he knew, or if the change,

this once, was not his own.

For he lived as the moon does,

strange and bright, inconstant

as time itself, casting fluid

shadows into space.

And if we felt some echo

in his forms, his songs, his life,

the moon would not do less.

He died at the dark of the moon

at the moment when all things change.

And he died as the moon does,

with its face turned out, away.

Gone from our sight forever.

Gone, for a while.

Gone, but no less bright.

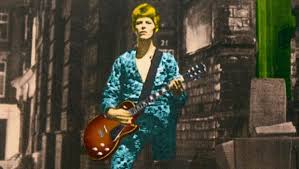

Bowie: We can be heroes, just for one day

Posted by cathannabel in Music on January 11, 2016

Fascinating Bowie tribute focusing on Bowie in Berlin, from That’s How the Light Gets In.

Ch-ch-changes

Just gonna have to be a different man…

In Berlin: Imagine a City, Rory MacLean writes of how, in 1976, ‘rock ‘n’ roll’s blazing star fell to earth in Berlin. Bowie arrived in the city a haunted, haggard wreck: barely six stones, sleepless and wired on cocaine, possessing little sense of his own self-worth. ‘I really did have doubts about my sanity’, Bowie wrote later. But, according to MacLean, Bowie found himself in Berlin (and he might know since, fresh out of film school, he was a young assistant to the director on the film shot in the city at the time, Just a Gigolo).

View original post 769 more words

Loving the alien

Posted by cathannabel in Music on January 11, 2016

Three moments from the early 1970s.

Suffragette City

1972, the Cellar Bar at the Hutt, Ravenshead, Notts. The Hutt was a Berni Inn, purveyor of prawn cocktail, steak & chips, and Black Forest gateaux – but the Cellar Bar was a dark and crowded space where a 14 year old could get served with Babycham or Bacardi & lime, and where the juke box was turned up LOUD. I didn’t even know this was Bowie, I just knew it was exhilarating, intoxicating. And dangerous.

Star Man

Seeing that clip now from Top of the Pops, it’s hard – impossible even – to make sense of how shocking, how ridiculously daring and provocative it seemed at the time when he draped his arm so casually around Mick Ronson’s shoulders and they sang together, close. There was no other topic of conversation the next morning at school in Mansfield. But for some of those boys and girls who knew they could never conform to the gender roles assigned to them, who knew they were different, and were scared and thought they might be the only ones who felt that way, it was a moment that changed their worlds, it gave them hope and courage.

Time

Listening to Aladdin Sane on the record player in our living room, staying within arms reach of the volume control so that we could ramp it down speedily if the parents came within earshot at the point when the lyrics got seriously inappropriate.

Listening to Aladdin Sane on the record player in our living room, staying within arms reach of the volume control so that we could ramp it down speedily if the parents came within earshot at the point when the lyrics got seriously inappropriate.

Bowie was the unifying factor in the otherwise rigid musical demarcations of the time. I loved Motown, Simon & Garfunkel, and Bowie. My friends loved Alice Cooper, Deep Purple, and Bowie. My brother loved Gong, Hatfield & the North, and Bowie. And as for the boy who is now my husband of 38 years, who introduced me to Hendrix and Crimson, amongst others (and who I introduced to Motown and reggae) – Bowie was our musical meeting place. The fact that he could play some of the songs – well, reader, I married him…

It is those memories that are the most powerful, from those teenage years when everything was so intense, when we were trying to work out who we were and who we wanted to be. Bowie was part of that – he made us question, made us imagine possibilities, showed us we could reinvent ourselves if we wished.

That continued through the decades since – we backtracked from Ziggy to Hunky Dory and Man Who Sold the World, and even to the early singles when he was Davie Jones, with the King Bees, The Lower Third, and various other short-lived bands. No amount of nostalgia or grief will make me remember The Laughing Gnome with fondness, or some of the other early tracks. But even then, there was the sense of someone who would try anything, experiment fearlessly, take risks. And the variety was dizzying, from the heavy rock of Width of a Circle, to the delicate An Occasional Dream or the whimsy of Kooks.

We awaited each new album with a mixture of excitement and trepidation – would he let us down? would this one disappoint? No, and no. And how extraordinary that on Saturday night, just a day and a half ago, we prepared ourselves to listen to the new Bowie album, by playing the Ziggy Stardust farewell gig and Philip Glass’s Low Symphony. And he didn’t let us down. This one did not disappoint. I tweeted that night:

#musicnight No other artist that I’ve been listening to for > 40 yrs is still doing new stuff today, still sounding so fresh.

And then this morning I woke to the news that he is gone.

So tonight, we will play songs from across all of the years in which Bowie has been part of our lives. We will raise a glass to the Starman, and probably get a little drunk and sing along, and cry a bit. He may be gone but we have so much music, enough to sustain us, enough to inspire us.

Don’t let me hear you say life’s

taking you nowhere,

angelCome get up my baby

Look at that sky, life’s begun

Nights are warm and the days are young