Archive for September, 2018

Ten Books*

Posted by cathannabel in Literature on September 9, 2018

*Disclaimer – there are a lot more than ten books. I don’t automatically have a problem with compliance, but to attempt to distill 57 years of reading into just ten books would be just silly. Far harder, in a way, than the Ten Albums thing I did a while back.

Anyway, despite all of that, reading other people’s selections on Facebook did get me thinking about the books that have had the greatest impact on me, made me the person I am. So I’ve devised a plan. I’ve picked some of the books I read as a child or in my early teens, during those years of eager discovery, every book a new world to explore. I’ve grouped them not into genres (I have no truck with categorisation by genre) but in terms of ten themes and ideas that these books encapsulated and which set me on quests that I’m still pursuing today. Secondly, I’ve picked ten(ish) of the books that I’ve read as an adult that have inspired me and that have informed my politics. Neither of these lists represents The Best, but all the books here have been truly significant.

A Childhood with my Head in a Book

How to Be a Girl

The books I read as a child gave me some interesting and contradictory models for how to be a girl. It’s something I was never very good at – my Christmases and birthdays always brought cookery books, dolls and sewing kits, none of which inspired anything other than indifference in me. I only ever completed one bit of knitting – my treasured Forest scarf. You can tell which end I started at, from the loose, uneven stitches. I tired rapidly of the pious and/or relentlessly cheerful heroines that an earlier generation of writers so often presented to me, but found among that generation nonetheless the likes of Anne Shirley and Jo March who gave me the notion that being a girl might involve reading a lot, using your imagination, defying convention, being contrary, not being Good (at least not all the time).

I read Jane Eyre – another awkward girl – at a young age. (This was one of a number of classics which were technically too old for me, but which, because they began with the protagonist as a child, were accessible even if their full depth and complexity were only revealed through later re-reading – see also Great Expectations, David Copperfield.) Jane Eyre led me to read the rest of the Brontes (though only recently in the case of Anne, I’m ashamed to say), and the Dickens I read as a child led me to read all of his work, and to explore the world of the nineteenth-century novel, particularly George Eliot, who I read as a teenager but whose Middlemarch vies with Bleak House for the title of Greatest Novel in the English Language (spoiler – BH wins. Just).

And I Capture the Castle, in which we meet Cassandra Mortmain (sitting in the kitchen sink) at the age of 17 (‘looks younger, feels older’) – a marvellous mixture of naivety and wisdom. Far older than me when I read it first, so I grew up with her, catching up and then overtaking her.

L M Montgomery – Anne of Green Gables; Louisa May Alcott – Little Women; Charlotte Bronte – Jane Eyre; Dodie Smith – I Capture the Castle

Travellers in Time

I was always entranced by the notion of slipping from now to then, from present to past. And these three books all share something in common – that the slippage is related to a very specific and real place, a place in which the past is still very present. Dethick, in Derbyshire, is the real counterpart of Alison Uttley’s Thackers (A Traveller in Time); Philippa Pearce’s Victorian house (Tom’s Midnight Garden) is based on the Mill House in Great Shelford, near Cambridge, and Lucy Boston based Green Knowe (The Children of Green Knowe and its sequels) on her home, The Manor in Hemingford Grey, also near Cambridge. My very talented friend Clare Trowell now lives in Hemingford Grey, and this gorgeous linocut is her tribute to a book that is as magical for her as it is for me.

Clare Trowell (linocut) – Hemingford Grey

In each of these novels, the present-day protagonist encounters past inhabitants of that house, and there is both a sense of magic and a deep sadness that comes from the knowledge that those people are in today’s reality long gone. Although in Tom’s Midnight Garden, there is an encounter between the boy and the elderly woman who was/is the young Victorian girl who had become his friend, which brings about one of the most poignant endings in children’s literature (yes, up there with the final pages of The Railway Children about which I cannot even speak without choking up). I found Dethick in my early teens and will never forget the sense of magic, just out of my reach, when I stood in the Tudor kitchen of the old house, where Penelope had stood, where she had encountered the Babingtons. And I still get that same feeling when I see the ruins of Wingfield Manor on the skyline.

I’ve read many books since then that play with time travel (the most powerful is probably Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveller’s Wife, whose ending made me sob like a baby), and it’s a staple of the sci-fi I watch on screens large and small, but the magic these books hold is different. It’s not about the intellectual tease of time paradoxes, or parallel dimensions. It’s about a place, and the people who inhabited that place, and whose joys and sorrows still inhabit it long after they’re gone.

Alison Uttley – A Traveller in Time; Philippa Pearce – Tom’s Midnight Garden; Lucy M Boston – The Children of Green Knowe

Thresholds to Other Worlds

And then there are the books in which the protagonists slip not just out of our time, but out of our world and into another, or into a version of our world where magic is real, if invisible. Harry Potter was obviously not a part of my childhood, so the first doorway into myth and magic that I encountered was a wardrobe door, and it led to a place of permanent winter, always winter but never Christmas. I know there are issues with the Narnia books – and when reading them aloud to my own children I did skip one or two sentences of egregious sexism or racism. But they are a part of me, read and re-read, fuelling my imagination and my curiosity, still shared reference points with family and friends.

Not long after discovering Narnia, I found in the pages of Alan Garner’s The Weirdstone of Brisingamen the gates to Fundindelve on Alderley Edge and stories that were not only magical but genuinely spinechilling. Like the time-slip stories mentioned previously, Garner’s stories are absolutely rooted in the landscape he knew, and steeped in the multilayered mythologies of the British Isles – Celtic and Norse and Saxon. Many of the places referred to in The Weirdstone and The Moon of Gomrath can be found not only on the frontispiece map provided (I do like a story that comes with a map) but on the OS map of the area.

One can go on a pilgrimage – as I did – and find these locations and feel that frisson of magic again.

Whereas Lewis’s protagonists are largely unencumbered by adults, as is so frequently the case in children’s literature, in Garner’s narratives the adults can be allies, however reluctantly roped into the struggle between good and evil that is being played out around them, or they can be obstacles or enemies. Those encounters with evil are all the more terrifying when they encroach upon the ordinary, everyday world – something that Stephen King knows very well. Garner’s approach is similar to that of Susan Cooper in her marvellous The Dark is Rising series, which is only not included here because I didn’t encounter those books until my late teens. I grew up with Garner’s books – in the literal sense that the transition from Weirdstone/Moon to Elidor and thus to The Owl Service and Red Shift was a gradual transition from childhood to young adulthood in terms of the themes and the sensibilities of the protagonists.

C S Lewis – Chronicles of Narnia; Alan Garner – The Weirdstone of Brisingamen

Other Worlds

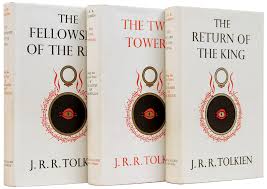

Whilst Narnia could be accessed from our world, via a wardrobe or a painting or a summons, Middle Earth exists outside our world altogether. I read The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings trilogy as a child and was utterly terrified by the Dark Riders, and Shelob. Ursula le Guin’s Earthsea was another other world that I came to late in my teens – it led me to her adult science fiction novels which are beautiful and profound and which make the reader think and question. Lord of the Rings doesn’t really do those things but it catches you up in the archetypal quest narrative with the archetypal quest hero, not a warrior or a king but someone (literally) small and naive, someone whose resolve is strong but yet falters and who needs other people (friends and enemies) to achieve his goal.

J R R Tolkien – The Lord of the Rings

The Past

Some of the books I read took me into the past, unmediated by a present-day interloper. Rosemary Sutcliff illuminated the Roman period and its aftermath, and Henry Treece the Vikings. Rosemary Hawley Jarman’s romantic take on the Wars of the Roses and, particularly, the mission to clear the name of Richard III (see also Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time) captivated me. Leon Garfield’s protagonists weren’t real historical figures but inhabited a richly drawn eighteenth-century world. And Joan Aiken introduced me to the notion of alternative history, with her splendidly Gothic Wolves of Willoughby Chase set in the reign of James III. I loved Edith Sitwell’s studies of Elizabeth 1 in Fanfare for Elizabeth and The Queens and the Hive. I loved Margaret Irwin’s take on the same period in her Queen Elizabeth trilogy, as well as her accounts of Prince Rupert of the Rhine and Minette (sister to Charles II). All of these writers fed my fascination with history and led me to contemporary writers such as Hilary Mantel and Livi Michael.

Rosemary Sutcliff – The Lantern Bearers; Leon Garfield – Smith; Joan Aiken – The Wolves of Willoughby Chase; Henry Treece – Viking’s Dawn; Rosemary Hawley Jarman – We Speak no Treason; Edith Sitwell – Fanfare for Elizabeth; Margaret Irwin – Young Bess

Displaced and Endangered

Whilst it’s far from unusual that the protagonists of novels for children are parentless, either permanently (a heck of a lot of orphans) or temporarily, some of the novels I encountered as a child took that trope of children pluckily dealing with perils of various kinds, and gave it a much darker context, and a much more real peril.

The children in Ian Serraillier’s The Silver Sword escape occupied Warsaw and after the war is over have to try to find their families amidst the chaos and mass displacement, as well as the emerging tensions between the former Allies. It’s tough and powerful, whilst also being a cracking adventure. The protagonist of Ann Holm’s I am David escapes (with the collusion of a guard) from a prison camp in an unnamed country and crosses Europe to try to find his mother. The novel does not flinch from the ways in which David has been affected by his life in the camp and how difficult he finds it to trust given his early experiences. An Rutgers van der Loeff told the story of a group of children who found themselves on the Oregon trail alone, after their parents died on the journey (based to some extent on the true story of the Sager orphans). It was often a harsh read, and again did not shy away from the emotional effect of having to assume adulthood at 14 and take responsibility for the safety of younger siblings in a world full of natural and man-made threats. Meindert de Jong’s The House of Sixty Fathers is set during the Sino-Japanese war, and again tells of a child separated from his parents in the chaos of war, but in this case finding care and love from a unit of American soldiers (the titular Sixty Fathers).

All of these books pull their punches to some extent. They don’t present their child readers with the full, unmitigated horror of war or of genocide. And they are right, in my view, to hold back. What they do is to open that door, just enough, so that readers can choose to find out more, and are prepared (to some extent) for what they may discover.

Ian Serraillier – The Silver Sword; Ann Holm – I Am David; An Rutgers van der Loeff – Children on the Oregon Trail; Meindert de Jong – The House of Sixty Fathers

Everyday Magic

There’s another kind of magic, that doesn’t tap into myth and legend but imaginatively imbues ordinary life with something extraordinary. Here, the extraordinary is very small. So small that it can be hidden from prying eyes, it can live alongside us but without us knowing. Mary Norton’s Borrowers series was both magical and mundane – the prosaic details of the Clock family’s life beneath the floorboards, appropriating household objects – cotton reels, hairpins, old kid gloves – and using them to create a miniature version of the life of the human beans above, was somehow so easy to engage with. What did happen to all those tiny things that mysteriously go missing – could this be the answer? The fascination with things miniature – dolls’ houses, miniature villages (both of which feature in the narrative) is widely shared and Norton taps into this. The small people in T H White’s Mistress Masham’s Repose are actual bona fide Lilliputians and our heroine, Maria, an orphan (natch) finds her own salvation linked to theirs, in the face of callous and exploitative adults.

Mary Norton – The Borrowers; T H White – Mistress Masham’s Repose

Myths & Legends

As well as novels in which myth and legend intruded into contemporary life, I read various versions of the originals. Roger Lancelyn Green was one of the best, bringing me retellings of Greek, Norse, Celtic and Egyptian legends. He was one of my original sources for the stories of King Arthur, which entranced me and continue to inhabit my imagination to this day (they’ve inspired the names of both of my children). Reading both Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, which sets the tales in a medieval world of chivalric valour, and Rosemary Sutcliff’s interpretation of Arthur as Celtic warrior drew me into the complexity of the myth.

Roger Lancelyn Green – Tales of the Greek Heroes; Rosemary Sutcliff – Sword at Sunset

SciFi

Fantasy and myth led me into proper sci-fi. The dividing lines between the two are often blurred and disputed but I guess at its simplest it relates to an interest in causes and process to ‘explain’ the phenomena that myth might simply present to us as a given. My first introduction was probably reading a volume of H G Wells’ science fiction, and it was The Invisible Man that had the most impact upon me (slightly surprising, perhaps, in view of my interest in timey-wimey narratives). From my parents’ bookshelves I scavenged John Wyndham’s novels, and his first three in particular (The Day of the Triffids, The Kraken Wakes, and The Chrysalids). These prepared the ground for so many dystopias and disaster movies to come…

H G Wells – The Invisible Man; John Wyndham – The Chrysalids

Reading the Detectives

As my current reading is often dominated by crime fiction, I was interested to explore the origins of that interest in my childhood reading. I was lucky enough to encounter Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories in the volumes of the Strand Magazine that my mother had inherited. Also through my parents I discovered Dorothy L Sayers’ Peter Wimsey novels, which I re-read happily today, because whether or not one can remember who did it, one can relish the writing, the dialogue, the wit. And linking in with my historical interests, Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time introduced the idea of a review of a very cold case, of challenging accepted views of history through radical reinterpretation of sources.

Josephine Tey – The Daughter of Time; Arthur Conan Doyle – Sherlock Holmes; Dorothy L Sayers – Strong Poison

If anyone notices the preponderance of Puffin logos in the images above (which are where possible the covers of the very books over which I pored), that’s very apt. I relied upon regular dispatches of Puffin books to our various homes in West Africa to keep me supplied with enough quality reading matter.

Adult Life with my Head in a Book

I’ve divided this group of books into fiction and non-fiction. Again, I must repeat that these are not necessarily the Best, but they’re all books that had a huge, often visceral, impact on me, that changed me.

Fiction:

If Nobody Speaks of Remarkable Things/Reservoir 13

For my money, Jon McGregor is one of the finest contemporary novelists. If Nobody… was the first and still has the power to floor me emotionally, however many times I read it. Reservoir 13 is the most recent, and having read it the first time, I could only turn back to the beginning and read it again, to immerse myself in the turning of the seasons and the warmth and humanity of the writing and the characterisation.

The Stand

I’ve written previously about how my prejudices were overcome once I actually read a Stephen King novel. No matter how schlocky the cover (these days the cover art tends to be rather subtler), the narrative was so compelling that I had to keep reading, hunger and tiredness were irrelevant, I had to keep turning those pages. I’ve read pretty much everything he’s written, but this was the one that got me started – having read it cover to cover, I re-read it almost immediately, being conscious that the compulsion to find out what happened next had made me rush through the pages. King is a consummate storyteller, and there’s a moral focus too. Whilst he doesn’t avoid the gross-out, he always retains that sense of the distinction between good and evil, the choices that confront ordinary, flawed human beings. And he can make those ordinary flawed human beings who confront evil believable, lovable, not just admirable.

I’ve written previously about how my prejudices were overcome once I actually read a Stephen King novel. No matter how schlocky the cover (these days the cover art tends to be rather subtler), the narrative was so compelling that I had to keep reading, hunger and tiredness were irrelevant, I had to keep turning those pages. I’ve read pretty much everything he’s written, but this was the one that got me started – having read it cover to cover, I re-read it almost immediately, being conscious that the compulsion to find out what happened next had made me rush through the pages. King is a consummate storyteller, and there’s a moral focus too. Whilst he doesn’t avoid the gross-out, he always retains that sense of the distinction between good and evil, the choices that confront ordinary, flawed human beings. And he can make those ordinary flawed human beings who confront evil believable, lovable, not just admirable.

L’Emploi du Temps/The Emigrants

Obviously I had to include these two, since the first, Michel Butor’s 1956 novel set in a fictionalised version of Manchester, has been the focus of my research during my part-time French degree, and now my PhD, which explores the connections, the dialogue, between Butor and W G Sebald. Many of my blogs, particularly the earlier ones, talk about Butor and/or Sebald in various contexts (music, maps, labyrinths, Manchester, Paris, the Holocaust…). Butor made me read Proust, Sebald made me read Kafka (I think of the two I’m more grateful to Butor, but both are essential to understand twentieth-century European literature).

Half of a Yellow Sun

This is a brilliant, powerful novel. For me it had a personal, visceral impact, in its account of the massacres carried out in the north of Nigeria, during the bloody prelude to that country’s brutal civil war. Because I was living at the time in Zaria, in the north, and whilst my parents shielded me (I was 9 years old) from the horrors, I nonetheless knew that there were horrors, and learned as a teenager and an adult more about what my parents had witnessed, about the context and the history, and about what came after, too. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is a splendid writer and a clear and strong voice, drily humorous and perceptive.

The Womens Room

Marilyn French’s The Women’s Room isn’t one that would make the list solely on its literary merits. It’s well enough written, but its presence here is because I read it just at the point when I was not so much becoming a feminist, but realising that I was one. I read everything I could get my hands on – Germaine Greer, Betty Friedan, Kate Millett, Susan Brownmiller, Shulamith Firestone (best name ever!), Sheila Rowbotham, Simone de Beauvoir and more. But there are things that only fiction can do, and The Women’s Room illustrated and encapsulated so many of these arguments in the story of Mira and her friends. French herself said that it wasn’t a book about the women’s movement, rather a book about women’s lives today. And because there isn’t just one voice here, but many, we are free to disagree with the most extreme viewpoints without rejecting the whole thing. The novel was accessible in a way that most of the feminist writers listed above, frankly, aren’t. And whilst it attracted plenty of criticism, it changed hearts and minds, it made so many women feel that they weren’t alone in the way they felt about the way the world worked.

Fiction can do things that non-fiction, however well-written, however accessible, can’t. But very often fiction leads me to non-fiction – I want to know more about the place, the period, the events that the fiction describes. The next list is of books that illuminated what I read in the newspapers and in novels, and what I watched on TV and at the cinema. They may not be definitive works, they may have been overtaken by subsequent research, and for various reasons they aren’t books that I will read again and again, but they were my way into topics which have preoccupied me over very many years. If the overall impression is that, well, it’s all a bit grim, I can only acknowledge that as a true reflection of what I read. I don’t immerse myself in grimness for the sake of it but from a deep need to understand and the sense that as privileged as I am in so many ways I have no right to look away, to choose not to know. I still believe in humanity, despite everything.

We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families: Stories from Rwanda

I read the newspaper reports coming out of Rwanda in 1994 but it took me a long time to seek out the full story of what had happened there. Perhaps that’s partly because I knew how powerfully it would connect emotionally with what had been happening around me in Northern Nigeria in 1966. Philip Gourevitch’s 1998 book is not a definitive history of Rwanda, and arguably lacks some of the context that is necessary to understand why the genocide happened. But it’s clearly unreasonable to expect every book on a complex issue to cover everything, to be everything. Gourevitch’s focus is on the testimony of survivors, and thus on the accounts of specific atrocities. It’s vital and horrifying and heartbreaking.

The War Against The Jews, 1933-1945

My introduction to the Holocaust was, as for so many, reading Anne Frank’s diary. But her diary can only raise questions, not provide answers. She knew so little of what was happening to Jews in Amsterdam and across Europe, only what the adults with whom she shared the Annexe themselves knew and allowed her to hear. When we read her words we are encountering a real person, a child on the verge of adolescence, a bright child, who might have been ordinary or extraordinary, who knows, but whose circumstances were so extraordinary that we read her words weighed down by our own knowledge of what was happening around her, and what would happen to her. The simple questions – why did they have to hide? why did they have to die? – require answers not to be found within the pages of the diary. My next step was the TV series Holocaust – controversial and flawed but hugely valuable to a generation who suddenly saw how what happened to Anne Frank fitted within this huge picture, in which the members of one Jewish family between them encounter Kristallnacht, Aktion T4, the Warsaw Ghetto, Sobibor, Terezin, Auschwitz…

Holocaust led me to Lucy Davidowicz’s 1975 account of the war against the Jews. This is not the definitive study – as if there could be such a thing – and has been harshly criticised by Raul Hilberg in particular, for its lack of depth and rigour. But it got me started, it gave me an overview and led me to read extensively amongst the vast literature on the subject, exploring not just what happened, but why and how and who, and the implications for the generations since (Middle East politics and international law in particular).

And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic (1980–1985)

I remember during the mid-1980s the first newspaper articles about a ‘gay plague’, and the emerging moral panics, the information leaflets and the ‘tombstone’ advert on TV. Randy Shilts’ 1987 book was what made sense of that mess of misinformation, prejudice and ignorance. It’s a work of investigative journalism, particularly in relation to the response and actions of medical researchers, but it’s also, always, personal. As a gay man in San Francisco, Shilts was not writing about something that was happening to ‘others’ but something that was happening to his own community and, ultimately, to him (he was confirmed to be HIV positive in 1987, having declined to find out his status whilst writing the book in case it skewed his approach, and died in 1994, aged only 42). It’s an often shocking book, heartbreaking and as compelling a page-turner as any detective novel.

Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West

James Michener’s massive, sweeping novel based on the story of a Colorado town, Centennial, was my introduction to many aspects of American history. Michener transposed many historic events, in particular the Sand Creek massacre to his fictional location so that through the lives of people in that one town (more or less) the great themes of US history could be touched upon.

I was fairly well-versed in the Civil Rights movement, having read not only about Martin Luther King but about the Black Panthers, Angela Davis and George Jackson. But my knowledge of the story of the Native Americans was patchy, to say the least. I knew enough to be sure that the portrayal in the westerns I’d watched as a kid was at best simplistic or romanticised and at worst racist, but Centennial made me want to know much, much more.

Dee Brown’s book is explicitly an Indian history (published in 1970, when presumably that terminology was still felt to be OK….) in which the Native American peoples are at the heart of the story of their own land. It’s a brutal story – they were lied to and stolen from, they were forced into dependency and then vilified for that dependency, and they were murdered in huge numbers. Brown’s history takes us up to 1890 and the Wounded Knee Massacre (sometimes referred to as the Battle of Wounded Knee which gives a rather false impression) which is seen as marking the end of the ‘Indian Wars’ – though not the end of conflict or of killing.

I found out recently about a series of murders of Osage people in Oklahoma in the early 1920s, motivated by the discovery of big oil deposits beneath their land and involving legal trickery to secure the inheritance of the victims (whose deaths were initially seen as being from natural causes). David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon is a fascinating read, a true-crime account which takes the story of the genocide a generation onwards, a small-scale version of what happened to the indigenous peoples across the continent.

All the President’s Men

This could scarcely be more pertinent, as Bob Woodward, one of the Washington Post reporters responsible for this account of the Watergate break-in and the scandal that brought down President Nixon has just published Fear: Trump in the White House… At the time it was all happening I followed events avidly, finding it hard to credit that such a plan could have been dreamed up, executed (incompetently) and then covered up (incompetently) at such high levels of government. The intervening years have made it easier to believe such things… This book, which appeared as the story was still fresh and new, was a brilliant piece of journalism, with all of the tension of a detective story. There was a follow-up, The Final Days, describing the end of Nixon’s presidency, and many other books, including from some of those implicated (such as John Ehrlichman, whose account was the basis of the 1977 TV mini-series, Washington: Behind Closed Doors, in which an all-star cast portray President Richard Monckton and his aides, associates and accomplices).

So, that’s my ten books… Ten themes in the books I devoured as a child, ten books (five – oh, OK, seven if you’re going to be picky – fiction, five non-fiction) that I read as an adult that have in one way or another stayed with me. I was never going to be able to pick just ten, was I?