Archive for category Music

Music Nights

Posted by cathannabel in Music on December 22, 2023

Each year I write about the books I’ve read, and the films and TV I’ve watched. Obviously I hope to entertain others when I do this, but it’s also to remind myself, to ensure that I’m not just consuming and forgetting, but thinking about them, analysing how (if) they work, as well as my own response to them. It’s very nerdy, I know, but that’s who I am.

But I don’t do the same for the music I’ve listened to through the year. I often at least list the live gigs I’ve been to, whether that be Tramlines festival or Opera North, but I don’t write about music. Part of that is that I’ve spent many years as a student writing about books and films – I kind of know how to approach that. When I try to write about music, I find I’m only really writing about my response to it (it made me feel joyful/weepy/like dancing/at peace…) rather than analysing the music itself, and that’s fine, because music defies being pinned down by words.

But music is a huge part of my life. And it was a huge part of my life with Martyn, and that’s perhaps why I am thinking about it more now that I’m without him.

It was taken for granted that one or two nights a week would be devoted to just listening to – ‘background music’ was an oxymoron to him – and talking about the music (other conversational avenues were discouraged, other than for emergency purposes). And those music nights took a particular form. With a vast CD collection to choose from, we had to find a way of listening not just to the usual suspects but to the more obscure artists, or at least the more obscure albums by more familiar artists. Not only that, but it meant that we could swerve from one century, one continent, one genre to another, never get stuck in one particular groove.

So the random music generator came into being. Dice were rolled to determine which column, which shelf in that column, and which album on that shelf would be played. Some leeway was permitted, if the selected CD had been played very recently, for example, but otherwise it was a given that we would play whatever was chosen. There were also occasions on which other mechanisms for choice were allowed, such as the recent death of a musician, in which case the choice would be from within her/his oeuvre, but favouring the more obscure rather than the best known work. It was a serious business.

And there was another wrinkle too. He was the wielder of the dice, and therefore obviously knew what it was we were about to hear. I didn’t, and so I was invited to guess (what, or at least who). This ranged from easy peasy to absolutely impossible, and getting it wrong risked a raised eyebrow of disdain. But it made me listen, more intently than I would have done otherwise, and think about what I was hearing, and that was the point really, not one-upmanship, given that he already knew the answer, but listening as a serious business, as the main business of the evening rather than as a background to doing other things.

When he died, I realised straight away that music nights were going to need a major rethink. First of all, the whole idea of sitting on my own and listening to music that intently seemed impossible, so laden with memories and with the awareness of that huge loss, that I couldn’t see how I would be able to face it. And when I did venture to put CDs on, I initially headed for the known rather than the obscure, the comfort of familiar voices and riffs.

My first musical project after he died was to choose the music for the funeral. It was clear to us from the start that the ceremony would be more music than words, because it was about him. And which music – that felt like a huge responsibility. How could I risk choosing something that would merit a raised eyebrow of disdain? But we came up with a list – and booked a double slot at the crem to allow enough time for all of the tracks, as well as the two poems, and the eulogies that each of the three of us had written.

- Philip Glass – Warszawa (3rd movement, Low Symphony)

- The Beach Boys – Our Prayer

- Stan Tracey Orchestra – Come Sunday (Ellington composition, instrumental version)

- Gerry Mulligan Quartet with Chet Baker – My Funny Valentine (instrumental version)

- Miles Davis – Florence sur les Champs-Elysée

- The Beatles – In My Life

- Jimi Hendrix – Pali Gap

And then there was the playlist for the wake. We ended up with about 13 hours of music, according to Spotify. Played on random, it bounces around across the decades, the continents and the genres (OK, there are no symphonies, concerti or string quartets in there). Putting it together was a labour of love. Tracks weren’t selected for poignancy or solemnity, rather the whole thing was a celebration of the music that we’d shared, that we both loved. Listening to it now, there are tracks I’d entirely forgotten that we’d included, and tracks that seem to come up every time. There are tracks that he loved more than I did, and vice versa. In other words, it is a true reflection of our musical lives together. And every now and again I am overwhelmed by the sadness that we’re not listening together, not any more.

I’ve had weeks since then when I listened to no music at all – something that would have been unthinkable before. But I knew that I needed to find it a place in my new life, and I have done. I’ve been to concerts on my own or with friends or family, I’ve been to Tramlines festival twice. Those have been comparatively easy. Once I’m there, sitting (or standing) and listening intently is the only option, whereas at home it’s too easy to persuade myself that I’m not really in the mood and reach for the TV remote instead.

But I had to have music nights again.

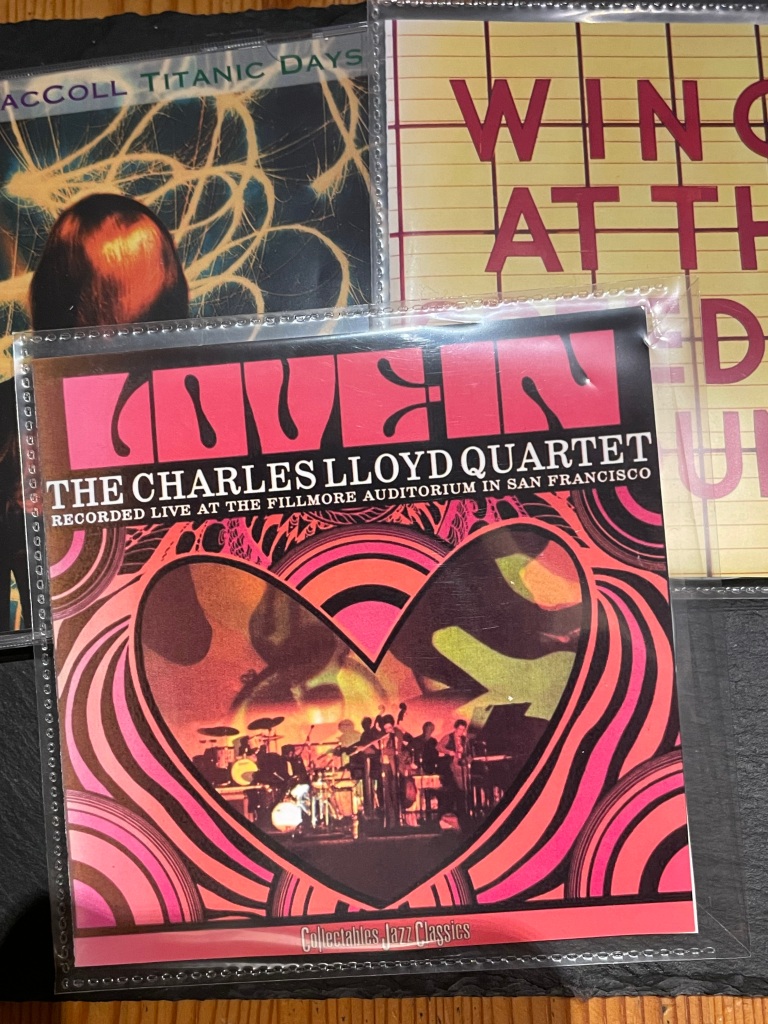

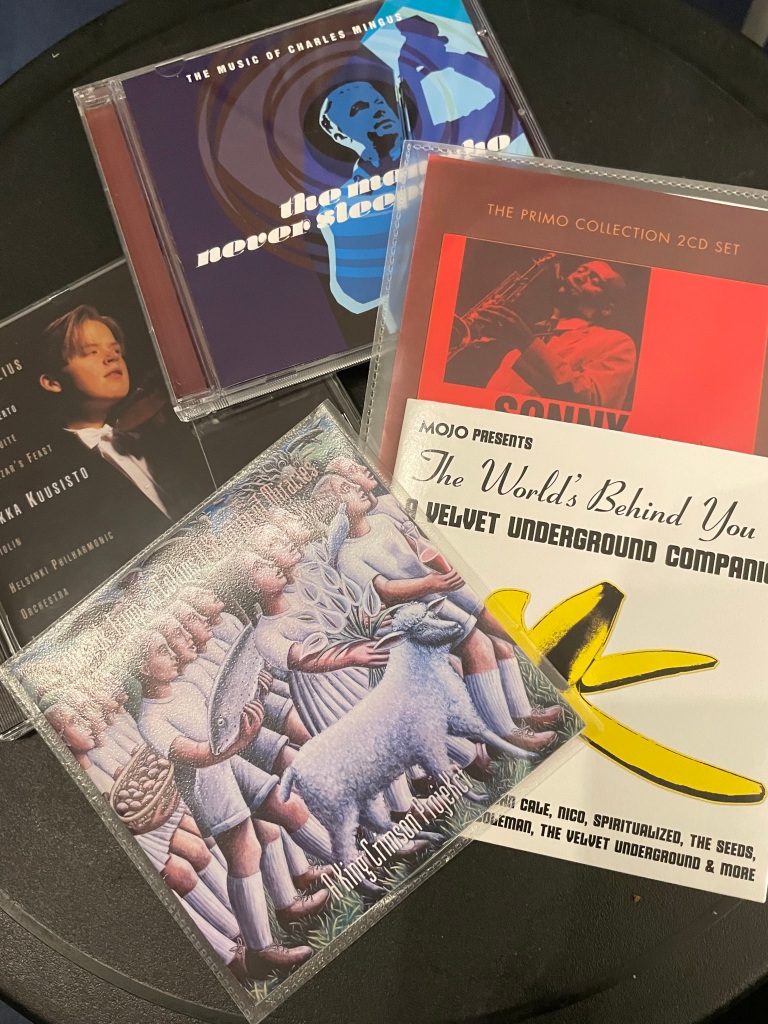

I found the dice, and I use those sometimes to narrow my search – when you have a whole dining room wall of CDs, it can be too daunting to try to pick something, so letting the random music generator do its work takes some of the pressure off, and elicits some surprises, albums I didn’t know we had, that I can’t be sure I ever listened to before, as well as things I know and just hadn’t listened to in years. I listen on Saturday afternoons to Radio 3, where there’s a run of programmes that deliver an eclectic range of music (This Classical Life, Inside Music, Sound of Cinema, Music Planet and J to Z) and on Sunday afternoon to Jazz Record Requests, and often these programmes suggest where my music night might go. There are other prompts – often something during the week reminds me of an artist or an album and so I start to make a little pile of CDs, to make it easy to get started and not to cop out.

The thing is, there isn’t any music that has nothing to do with him, and with our life together. Right from the start music was a vital connection between us. I remember going round to his house, with a few other people including my then boyfriend, and Martyn playing Bowie songs on the guitar. I think it was all settled in that moment, really. We introduced each other to the music that each of us loved – he played me Hendrix, ELP and Crimson, I brought him Motown, Osibisa and Simon & Garfunkel. We were each open to the other’s music, then and always. Actually, he was open to all music, then and always (although he never did quite come to terms with opera – the music is great, he’d say, if they’d just stop the warbling). Together, over the years, we explored jazz in its many forms, world music from literally the world, the whole gamut of pop, rock, soul, indie, blues, R&B, prog, folk-rock, jazz rock, post-rock, rap, country & western, the classical repertoire from Tallis through to Caroline Shaw…

So music will always be about me and him, even if I’m listening to things he never got to hear. I’ll always be having a conversation in my head with him when I’m listening, when there’s a bit I particularly like or that I think he’d particularly like, when I’m not sure I’m really getting it; whatever I’m thinking and feeling about the music is a conversation with him.

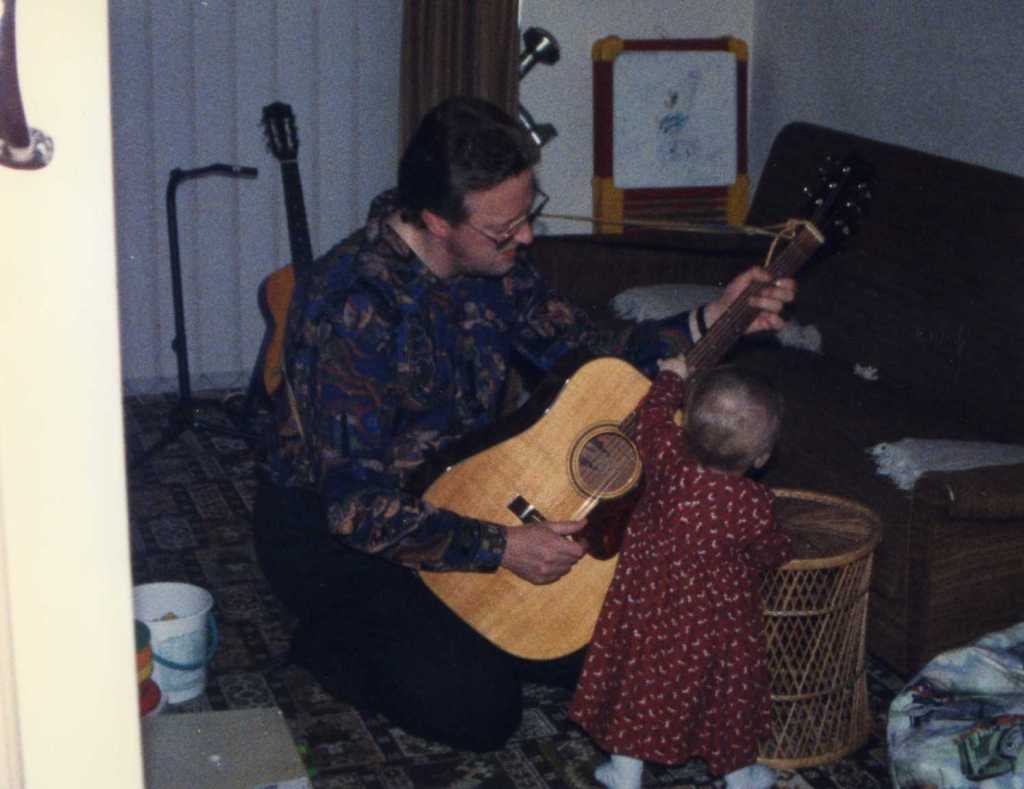

He listened differently to me, primarily because he was a musician. He could get music out of any musical instrument and he couldn’t see a musical instrument without wanting to play it. He never ‘learned properly’ as his mum (a piano teacher) always put it, but he could improvise on any fragment of a tune, which she couldn’t (his dad could though – he used to sit at the piano and vamp away a la Charlie Kunz). He was in two bands (on guitar or keyboards), Red Shift (with Paul and Chris), and the Conduits (with Jonathan (Yozzer), Tim, Jon, Dan and Lenny, and various guest musicians). There were a few gigs (at one of which I got to utter the immortal words, ‘I’m with the band’) but a lot more jam sessions, which suited Martyn well. Like his idol, Hendrix, he would jam with anyone who was willing to go where the music took them, seeking not perfection but the exhilaration of making something new. He recorded every one of those jam sessions, and would get home, and listen to the recordings, and transfer them from mini-disc to CD, for posterity (his brother Adrian is curating the very considerable library of recordings that he left behind). I haven’t yet played any of the recordings – I’m not ready to hear him, not just yet.

Martyn never really understood why I was content to be a music listener and not a music maker – I tried, but strumming chords on the guitar was, for me, a glum business and I could only follow what I was told to do, I could never launch myself into a jam. But though we listened differently, we always listened together.

Listening to music without him is a hazardous business – sometimes it’s too much. In all the exhilaration of discovering new music, the pleasure of hearing familiar music, I can be ambushed by sadness.

But if the alternative is to treat music as a background, to deny it its place at the heart of my life, to deny myself that exhilaration and delight, then I’ll settle for being ambushed. I don’t go in a lot for saying ‘it’s what he would have wanted’ – all too often that’s a way of quietening one’s unease about decisions that now have to be taken alone – but in this case, there’s no doubt. He would not wish for me in any circumstances a life without music, the thought would appal him. And for me, it would mean losing him in a most profound way.

When I told a friend how I was feeling about listening to music alone, he pointed out that since long before Martyn died, I have tweeted (as we used to call it) and posted on Facebook about our evenings’ listening. And how very often, someone out there connects with what I’ve posted, and enthuses with me, or suggests other things I might enjoy. So perhaps I’m not alone, not quite, after all.

2023 music nights, at home, 99% CD with the occasional foray on to Spotify, accompanied only by a glass or several of red wine (and random strangers via social media), brought me:

Arooj Aftab, Arnie Somogyi’s Ambulance, Daymé Arocena, Bacharach, Bagadou (French bagpipes), The Band, Bartok, The Beatles, Beats & Pieces, Jeff Beck, Tony Bennett, Art Blakey, Carla Bley, Bloc Party, David Bowie, Jean de Cambefort, Charpentier, Carmen Consoli, Corelli, David Crosby, Miles Davis, Depeche Mode, Egg, Duke Ellington, Ensemble Instrumental National du Mali, Espen Eriksen Trio, Bill Evans, Graham Fitkin, Ella Fitzgerald, Flobots, Marvin Gaye, Genesis, Gentle Giant, Ghanaian highlife, Philip Glass, Charlie Haden, Herbie Hancock, Handel, Richard Hawley, Jimi Hendrix, Henry Cow, Indigo Girls, Isley Brothers, Jacszuk Fripp & Collins, Laura Karpman, Georgi Kurtag, Ant Law & Alex Hitchcock, Charles Lloyd, Yvonne Lyon, Kirsty MacColl, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Massive Attack, Curtis Mayfield, Joni Mitchell, various Mojo CDs, Monteverdi, Motown, Sinead O’Connor, Pixies, Pogues, Prefab Sprout, Projekt X, Queens of the Stone Age, Rachmaninov, Zoe Rahman, Red Rum Club, Max Richter, Sonny Rollins, SBB, Ryuchi Sakamoto, Scenes in the City, Self Esteem, Shakti, Sharp Little Bones, Caroline Shaw, Andy Sheppard, Wayne Shorter, Shostakovich, Sibelius, Smiths, Songhoy Blues, Stax, Steeleye Span, Sugababes, James Taylor, Teenage Fanclub, Telemann, Television, Temptations, Jake Thackray, Tinariwen, Tina Turner, Erkki-Sven Tuur, Unthanks, Velvet Underground, Vivaldi, Weather Report, White Stripes, Wings, YMO, Zutons

2023 gigs, some solo, most with family/friends (Arthur, Adi, Janie, Aid & Ruth, Jennie & Michael, Sam & Jen):

A highlight of Sheffield’s classical music year is the Chamber Music Festival (Crucible Playhouse), this year boldly curated by Kathy Stott. Featuring Ensemble 360 + Tine Thing Helseth (trumpet), Ruth Wall (harp), Amy Dickson (sax), with a fantastic programme of familiar and totally unfamiliar music. The concerts I attended featured: Barber, Boulanger, Coleridge-Taylor, Dvorak, De Falla, Fitkin, Francaix, Glass, Jacobsen & Aghaei, Martinu, Menotti, Meredith, Milhaud, Rachmaninov, Rodney Bennett, Saint Saens, Schubert, Schulhoff, Scott, Wall, and Weill

Music in the Round (Upper Chapel) – Ligeti, Dorati, Lutoslawski and Farkas

Sheffield Jazz (Crookes Social Club) – Beats & Pieces, Ant Law & Alex Hitchcock, Clark Tracy Quintet, Anthropology Band, Ivo Neame’s Dodeka

Platform4 Music (Arts Tower) – a few years back we went to a performance of Terry Riley’s In C, using the Arts Tower’s Paternoster lifts. For this gig, the same group used the Arts Tower space, and the lifts again, to create interweaving lines of music, receding and approaching, clashing and harmonising.

Self Esteem (O2) – one hell of a gig! I’d seen them/her before at Tramlines 2022, and was blown away (I’d also seen her a few years earlier as part of Slow Club, also at Tramlines). Outstanding.

Under the Stars (Yellow Arch) – I’m a trustee of Under the Stars, a charity that works with adults with learning disabilities through music and drama. This was a gig from one of the music groups and it was loud and joyous. We also had a slot at Tramlines (see below), as in previous years.

Tramlines (Hillsborough Park, which was muddy by the time we all arrived on Friday afternoon, and a complete swamp by the time we called it a day on Sunday pm, but it was grand, and we’ve already bought our tickets for next year). We saw: Bloc Party, Blossoms, Blu3, Alice Ede, Everly Pregnant Brothers, Safii Kaii, Mary Wallopers, Kate Nash, Pale Waves, Red Rum Club, Sea Girls, Sugababes, Under the Stars, Zutons

Jacqui Dankworth & the Carducci String Quartet (Howard Assembly Rooms) – a lovely gig to accompany Sonia Boyce’s exhibition, Feeling Her Way.

Fiona Bevan & Adam Beattie (Café #9) – a tiny, perfect venue and a perfect gig from this duo, vocal harmonies, double bass, piano and guitar

Hailu Ni Trio (Café #9) – Chinese soprano Hailu Ni accompanied by piano and violin, performing Tosti, Puccini, Chopin, Ponce, Tchaikovsky, Schubert, Strauss, Mancini, Lewis Capaldi, Christina Perri & Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Tom Townsend & Friends (Café #9) playing the songs of James Taylor and, by extension, Carole King and Joni Mitchell (‘River’). Gorgeous songs. I may have had a little cry when he sang ‘You’ve Got a Friend’.

Red Rum Club (Leadmill) – we’d seen them at Tramlines and knew we were in for a great night – huge energy, great tunes, and a trumpeter, what more could one ask?

Unthanks in Winter (Octagon) – fragments of familiar carols merging into Unthanks compositions or much older, less familiar carols, dream-like, as if you’re slipping in and out of your own time.

Here’s to 2024, to many more gigs, and many more music nights. Thanks, always, to Martyn, without whom there is so much music I would never have heard, and who helped me to really, really listen.

Ring out the old, ring in the new

Posted by cathannabel in Events, Music, Personal, Theatre on December 31, 2022

Every week, for the last three and a half years, I’ve posted on Facebook about ‘Good Things’. This isn’t a ‘let’s not talk about the bad stuff’ exercise – it acknowledges, explicitly, that the reason I’m doing it is because there is a lot of bad stuff, globally and personally, and it is thus important sometimes to home in on and hold on to the good that is there, even if that good stuff seems rather small and trivial in comparison to war and climate change and poverty and everything. It’s not ‘always look on the bright side’ so much as ‘always look for the bright moments’. Older readers might think of the 1913 children’s book Pollyanna, whose central character is known for being relentlessly cheery at all times. Whilst this can be rather cloying, and I would refute the notion that there is something good to be found in every situation, the idea that it is healthy to remind oneself that there are good things is a valid one. Which is why I’ve kept those posts going, and why they invariably get likes and comments, and people urging me to continue.

It’s certainly not as if the period during which I’ve been doing this (and there were sporadic efforts before, my ‘reasons to be cheerful’) lent itself particularly to optimism, on any front. The world has been going to hell in a handcart faster than ever, it would seem. And on a personal level, when I posted my first ‘Good Things’ my youngest brother was terminally ill with cancer. He died the following February, just before the pandemic deprived us of so many of the things that might normally bring us comfort in hard times. Then, of course, in October 2021, I lost my husband. He died less than 24 hours after I’d posted that week’s Good Things, and when I re-read it I realised that despite the horror of what had happened, I stood by everything I’d said. Those good things were real and true and not invalidated by the huge Bad Thing that had engulfed us. So I’ve carried on.

It’s hard to find much on the national or global scale to celebrate – at most, some things didn’t turn out quite as badly as we feared (the US mid-terms, notably). Our government was incompetent and corrupt, chaotic and callous, as we’ve come to expect, and the usual people are suffering as a result – don’t be poor, don’t be disabled, don’t be old, don’t be sick, and for heaven’s sake, don’t be a refugee… Conspiracy theories, whether about climate change or vaccines or anything else one can think of, seem to be multiplying and spreading more rapidly each year, not helped by the takeover of Twitter, already an excellent breeding ground, by a leading conspiracy theory enabler and exponent. Ukraine is still suffering under – and fighting back against – the Russian invasion. Women in Afghanistan are shut out of the universities. It is easy to despair.

Of course there are always good people standing up for the vulnerable. The RNLI will carry on risking their members’ lives to save those whose dinghies are capsizing in the Channel. Food banks will continue handing out essentials to families who can’t make ends meet. Individuals and organisations will continue to provide safety nets, to challenge bigotry, to tell the truth and to shame (or at least try to shame) the powerful into using their power for good, and the brave will stand up anyway, in Iran and Afghanistan as in so many other places, whatever the risk.

In my own life, despite the sadness, I’ve had good things.

I got a new knee in February and (after a short but tough period of recovery) that gave me the confidence to be braver and more adventurous than I would have done otherwise. I went to Wembley to the Championship Playoff final, with my son. (The football has actually been a Good Thing in 2022, the first year for decades when I could have said that.) I went to Progfest with my brother in law and to the Tramlines music festival, with my son and with friends. I travelled to Rome, on my own (but was met by my brother, with whom I stayed). I would have done none of those things without the op, I would have been too scared, not only of the pain, but of my knee suddenly refusing to bear my weight, or of falling. That fear nearly paralysed me when he died – I could see myself so easily becoming virtually housebound, dependent entirely on others to get around, and that hasn’t happened.

I have needed more help this year, especially without a car or someone to drive it, and I’ve always found the help that I’ve needed, sometimes by asking very directly for it (anyone taller than me – i.e. most adults – entering the house is likely to be greeted on the doorstep with a request to change a light bulb or lift something down off a high shelf), at other times because some nice young man or woman has seen me struggling with a suitcase or whatever and has offered assistance. I’ve also found someone to help me with the cleaning, someone to help me with the garden, a handyman and a decorator.

I finished the PhD, submitting just over a week before he died, and had my viva in May. I’m very proud of the thesis, and I absolutely could not have done it without his support, in big ways and small – so many times I was writing away, lost in my work, only to realise that he had snuck in, delivered a hot cup of tea or coffee and snuck out again, without breaking my train of thought.

I’ve been to the theatre, to a stunning production of Much Ado, by Ramps on the Moon which used its cast of (mainly) deaf and disabled actors inventively and boldly, and tweaked the text accordingly. Much Ado works or doesn’t depending on Beatrice and Benedick, and here both were outstanding and unforgettable. The Guardian reviewer described Daneka Etchell (who is autistic) as ‘the most compelling Beatrice you might ever see’, and she was responsible for an extraordinary scene, when, in her distress at the injustice being inflicted on Hero, she starts stimming. Both her anguish and Benedick’s tenderness in trying to help calm her were very moving.

We very much enjoyed a performance by Under the Stars, an organisation who we supported with Martyn’s memorial fundraiser, who are an arts and events charity for people with learning disabilities and/or autism, running music and drama workshops and nightclubs. The play was The Many Journeys of Maria Rossini and it used words, music and dance, exuberantly and engagingly, to tell the story. Under the Stars band also performed at Tramlines.

Final theatre outing of the year was to Richard Hawley’s musical Standing at the Sky’s Edge, which we’d somehow missed when it was first produced at the Crucible in 2019. We loved it. The musical weaves together the stories of some of the inhabitants of Sheffield’s Park Hill flats, over five decades, telling those stories through some of Hawley’s songs. The action is beautifully choreographed, the singing is marvellous, and it builds to a very moving climax. Obviously this piece has special relevance and resonance for Sheffielders, but it goes beyond that – every major city has communities like Park Hill.

I’ve done my usual summaries of what I’ve read and watched over the year. As far as listening to music at home goes, I’ve tried to develop my own approach to music nights, which were so much about our shared enjoyment of music that initially I couldn’t see at all how I would do it. Now, I pick a few things over the course of the week, prompted by someone mentioning an artist or a band, by an artist’s death, or some other kind of event, just so that I don’t get paralysed by the vast choice when I look at our CD wall. I listen when I can to the Radio 3 weekend programmes we used to love, to Inside Music, Sound of Cinema, Music Planet, J to Z, Jazz Record Requests, and these also often suggest what I listen to from our collection.

Highlights amongst the music that I’ve heard live this year:

- Beethoven String Quartets plus a piece by Caroline Shaw (‘Entr’acte’), in a Music in the Round concert which I sponsored in Martyn’s memory, at the Crucible in May

- Focus, the highlight of the Progfest in April. Still led by Thijs van Leer, who may not be able to reach all the high notes these days but is still a great performer, and the band (which included Pierre van der Linden, another veteran) was great and of course the music brought back so many memories of listening with Martyn.

- Jazz Sheffield gigs from Laura Jurd, Zoe Rahman and the Espen Ericksen Trio with Andy Shephard, all excellent.

- Tramlines highlights: my old favourite, the Coral, and new favourite, Self Esteem.

- A rare orchestral concert, at a great venue, the Auditorium in Rome: Gershwin, Bernstein and Stravinsky.

Last New Year’s Day was one of the hardest to wake up to in all of the days since he died. Knowing that I was about to start on a year without him, the first year without him since 1973… It was bleak. Perhaps, whilst this NYE/NYD will acknowledge the sadness, it may be easier. I hope it will be less bleak, less raw.

So, allons-y to 2023. I will formally graduate (for the last time, definitely, categorically) on 11 January, and my next project will be to look for a publisher for a version of the thesis. I’ll have chapters published in two forthcoming books, both on W G Sebald. I’ll travel, to see friends in Scotland, to see family in various parts of the country, maybe a city break in Europe. I’ll go to two family weddings. I’ll finish phase 2 of the decorating, maybe even phase 3. I’ll carry on sharing the cultural riches of Sheffield with friends and family.

Without being Pollyanna-ish, I do know how very lucky I am, to be surrounded by people who want to and do help me, emotionally and practically. I am thankful for them, every day.

For you, I wish for health and strength, for peace and comfort, for love and support.

In 2023 I wish, of course, for a world without war, a world where people are not persecuted for their beliefs, or simply for who they are, a world where women can be safe on the streets and in their homes. I wish for action on climate change, before it’s too late. That’s a lot, I know.

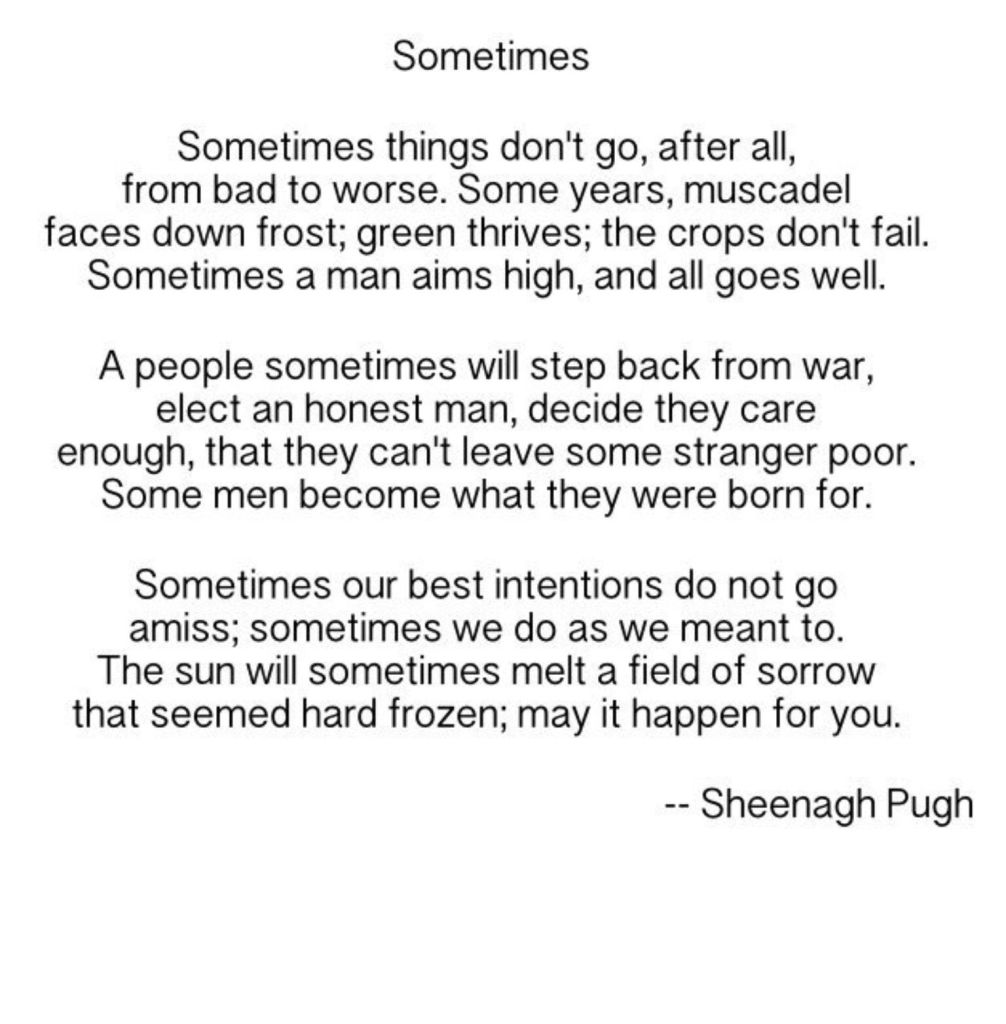

But as we go into another new year I think, as always, of this poem, which gives me hope.

2020 On Screen

Posted by cathannabel in Film, Music, Personal, Television on December 27, 2020

Normally, there’s quite a bit about cinema in this review of the year on screen. This year was, obviously, different, and whilst I could have watched more films on screen via DVD, for a host of reasons I found refuge in telly, in short bursts of drama rather than longer forms. My concentration was shot in the first part of the year, with the loss of my brother, and the onset of the pandemic.

I got used to the latter, to the extent that those of us who weren’t directly affected got used to it (finding new routines involving lots of local walks and evenings in, as we had the luxury of no work or financial pressures, plenty of space indoors and out, and no one close to us being ill).

As for the former, grieving isn’t a linear process, one can seem to be fine and then walk into a wall that wasn’t there before, one can seem to be fine and then be ambushed by a memory, an image, a word. So there are things we’ve avoided watching because, well, why deliberately provoke it? The exception to this was Little Women, of which more below, which we saw at the cinema very early in 2020, in full knowledge of how it would foreshadow the inevitable loss that we were facing.

The Small Screen

Please note: this reflects what we have watched in 2020, and thus includes old stuff that is circling eternally on ITV 3 and Drama, stuff from 2019 that was still sitting on our BT Vision Box as the year turned, as well as this year’s TV. This is the telly that has diverted, amused, intrigued, enlightened, moved and informed us during 2020. I’ve missed out the things that we started watching and then decided life was simply too short to waste time on, but, whilst I don’t normally spend much time talking about things I haven’t liked, there are a few dishonourable mentions here, mainly for things that I expected to like and in the end was very cross with. I’ve linked to some reviews, where they are not too spoilery, but as always, caveat lector.

You know you’ve watched too many episodes of Midsomer Murders when the ITV 3 intro causes eruptions of rage every single time it invites us to go to the ‘infamous village of Midsomer where only one thing’s for certain’. As any fule no, Midsomer is not a village but a county. I mean, that body count would be just too improbable in just one village, wouldn’t it? Another clue is when you overhear someone saying ‘Oh, hello, what are you doing here?’ and turn abruptly, expecting imminent violence with a pitchfork or perhaps a giant cheese. It’s very silly, and the writing is variable but at its best, it knows exactly what it’s doing, and there are lots of little in-jokes about the bloodthirsty nature of these picturesque villages (like the incoming DS from the Met who is shocked at the carnage). We’ve re-watched all the Nettles series, which allows us to marvel every episode at how Joyce manages to get involved in every single case, because she is a member of every single committee, book club, art class, choir, am dram group, and so forth in the entire county. I have my suspicions that she is actually the mastermind behind the whole murderous business.

There were lots more weighty contenders, of course. Foreign language offerings included Nordic crime from Twin, Before We Die, Wisting, and Below the Surface, and best of all The Bridge, whose first two series we had missed when they were first shown (I know! What were we thinking?) and enjoyed very much, whilst concluding that the plot, especially perhaps in Season 2, was a little too complex for its own good and if one was being picky one might mention a couple of possible holes. But one won’t, and one is now re-watching series 3 and 4. Saga is, of course, a most wonderful creation.

Wallander is obviously Nordic but Young Wallander is in English. It’s an oddity – if we hadn’t been alerted before watching we would have been most bemused by the contemporary setting. There are nods to ‘our’ Wallander (the father who paints the same scene over and over again, the girlfriend called Mona) but clearly this is not the equivalent of Endeavour. It was enjoyable, if not unmissable. Van der Valk is a remake of a 70s series which we never watched – again it’s in English but set in Amsterdam. The setting was, I fear, the best thing about it. The plots were ludicrously baroque, the motivation of the culprits unconvincing, the script clichéd – and if anyone wonders how I dare level such criticisms when I’ve just admitted to a fondness for Midsomer Murders, MM has a lightness, a touch of humour, that VdV lacked.

The latest series of Spiral had us shouting at the telly, primarily at Laure and Gilou. Excellent stuff – our deeply flawed heroes may be infuriating but they’re convincing and won our hearts a long while back, and the plot was gripping and tense. The other French offering was The Other Mother, based on Michel Bussi’s novel Maman a tort, which was also excellent – the plot was complex but just the right side of incomprehensible. The Team was a multinational European offering – it’s series 2 but with no characters in common from series 1, just the concept of a multinational team pulled together from different EU nations to solve a crime.

We also watched the movie Goldstone, which is linked to the Australian crime series Murder Road, whose new series is awaiting our attention, and the much lighter-weight but diverting Harrow, about an Aussie pathologist, the sort of pathologist who investigates crime, not the sort that gets called in when there’s a corpse and says ‘I’ll know more when I get him on the slab’ and then eats his sandwiches whilst foraging about in someone’s insides – see MM, Vera, et al. They know their place, unlike Harrow.

We visited the frozen landscapes of Canada for another dark and dour series of Cardinal, and back to the US for The Sinner (this was series 2, with only Bill Pullman in common with series 1). A much more unusual setting for Baghdad Central – an excellent, tautly plotted thriller with powerful performances by Waleed Zuaiter and Bertie Carvel. And we visited the past – Vienna in the 1900s -for Vienna Blood. The protagonists are an ‘unlikely duo’ of a brash young medical student and disciple of Freud, and a battered older cop, the production is very Sherlockian, and altogether it was slightly daft, but enjoyable, with a darker undercurrent running through it, of the endemic antisemitism of the time and the place, whose consequences we know too well.

Back in the UK, we enjoyed the Agatha Christie dramatization of The Pale Horse, with Rufus Sewell; Guilt, a blackly comic take on murder, with the always engaging Mark Bonnar; and McDonald & Dodds, with Jason Watkins, another lighter weight crime series, with good enough performances and writing to be worth catching when it returns. We watched Judge John Deed, which turned into a montage of 90s conspiracy theories about phone masts and the like, with improbable legal scenarios, and a protagonist whose compulsion to seduce every attractive woman he meets (key witness, fellow barrister, ex-wife, his therapist) becomes tiresome and frankly a bit creepy. Actually, all of the characters are intensely annoying, and one watched it mainly to be infuriated with it. Series 2 of Bancroft was just as ludicrous as the first.

The really good stuff:

Strike, Series 4 – charismatic leads, great plots, thoroughly enjoyable series, weaving the personal narratives of Strike and Robin in with the investigations very skilfully.

Hidden, Series 2 – Welsh noir – very, very noir – with an excellent female lead. As with the first series, the ending brings a very compromised and uncomfortable resolution.

Deadwater Fell – dark psychological drama, excellent cast, very unsettling.

Elizabeth is Missing – based on the book by Emma Healey. The lead character, Maud, has dementia, so when she insists that her friend Elizabeth is missing, no one takes her very seriously. Her recent memories keep getting mixed up with much older ones, of a much older disappearance. Glenda Jackson’s performance is absolutely mesmerisingly brilliant.

Dublin Murders – based on the first two books of the Tana French series. The plots are interwoven in a way that perhaps didn’t totally work, but the quality of the writing and the performances carried the day.

Endeavour – the penultimate series, apparently. The quality of the writing continues to be an absolute joy. The interplay between Morse, Strange, Thursday and Bright is so well played, often very emotionally powerful even though (or perhaps all the more because) none of them speak easily about their feelings.

Vera – Brenda Blethyn is a fine-looking woman, and so somewhat at odds with the descriptions in the novels, but she gets the character beautifully. The way in which the relationship with Joe’s replacement as DS is developed is convincing and touching (I particularly like the way he kneels to help her put on her crime scene shoe covers. As an older woman with dodgy knees I can so identify).

The Capture – about surveillance and deep fake images and whether or not we can trust what we see… A nicely paranoid atmosphere and a gradual blurring of the lines between right and wrong

Giri/Haji – my pick of the year, without a doubt. That it didn’t get commissioned for a second season speaks to a certain cowardice amongst the decision makers, but as the Independent’s reviewer says, it is pretty much faultless as it stands, so maybe it doesn’t need a sequel. This was stylish, often audacious, bloody, darkly humorous – really striking and memorable telly. Applause to all concerned.

Homeland returned for the last time. The final series was an encapsulation of everything that we’ve seen over its whole run, very consciously a drawing together of many of the threads from all the previous series, satisfying without being oversimplified. As a jazz fan I was delighted that Carrie’s love of jazz, rather forgotten about in recent series, was foregrounded in the final scenes, as the wonderful Kamasi Washington performed live on stage.

Deutschland 86 took us to the brink, everything in place for the collapse of the GDR and the destruction of the Wall. I hope we get one more series, to take these characters, and us, through those momentous events.

We would not normally have thought of watching The New Pope. The trailer, rather bafflingly, showed Jude Law in tiny (very tiny) Speedos walking along a beach, as women gazed, and fainted away, on either side. Hmmm. However, we knew that my brother had a moment on screen as one of the Cardinals gathered at a funeral, and we had to watch – and watch with full attention – to ensure we didn’t miss him. I’m glad we did – it was bonkers but beautiful. (So we got to see both of my brothers on screen this year, strangely enough, our Aidan in purple robes in The New Pope, and our Greg in an orange trackie at a football match over 40 years ago – see below.)

Philharmonia was bonkers too – the orchestral setting was unusual, and it was enjoyable, even if one didn’t ever believe a word of it.

The Accident was grim, and some of the plotting was a little bit careless, I thought – or maybe setting up for a second series where other things come to light? No idea. I just felt that – without giving too much away – a character was introduced who played a key role in events, but that role never seemed to be properly explored, and the images at the very end seemed, almost, to suggest that the truth was something other than the established official version. I may have imagined it! There were some powerful performances, from Sarah Lancashire and Joanna Scanlan in particular.

The Plot against America, adapted by David Simon (The Wire) from Philip Roth’s alt history, in which Charles Lindbergh, running on an America First ticket, wins the 1940 US election rather than FDR. It is, of course, incredibly topical (more so than the novel, which came out in 2004, when the events of 2016 could not have been imagined). It was powerful, incredibly tense, and subtle when it needed to be. Its final moments – and this is where it differed significantly from the book – with the central characters tensely awaiting the outcome of another election, hoping and fearing the outcome, kept coming back into my mind in November.

We’re saving up Small Axe. Looking forward so much to this.

Let’s draw a veil over the awful Batwoman. Wooden acting, clunky scripts, a plot that made no sense at all.

Devs – sci fi that’s about ideas, as much as it’s about tech. There was no predicting where this one was heading, or where it ended up. Whether it entirely made sense, I’m not sure, but it was, as the Guardian reviewer put it, a ‘deep, dark, wild ride’.

Dracula – yet another take on the Stoker original, this one was about as faithful as any of the others, but it really went for it, with conviction and style. As Lucy Mangan in the Guardian put it, ‘It’s a proper job […] And that means proper scares. No spoilers, but the one in the [redacted] when the [redacted] suddenly [redacted] had me clinging to the ceiling. I advise parental supervision at all times. My dad was annoyed at having to come over, but needs must when the devil calls and starts emanating from your screen.’

His Dark Materials – As always with a screen version of a book/series that I have loved with a real passion, I was anxious that the adaptation would mess it up. I needn’t have worried. The performances are grand, the visuals stunning, and it’s powerful stuff. We loved it, and are looking forward to Series 2.

Star Trek: Discovery – we’re through the wormhole now, and it’s Trek, Jim, but not as we know it. This allows for real character development, though if I were to be picky I’d ask them to rein in the reaction shots of awe and wonderment and so forth. No idea where we’re headed but we’re now liberated from the need to be consistent with the existing series, which is pretty exciting, if you’re a long-term Trekker.

Star Trek: Picard – it’s a good time to be into Trek! Not only Discovery, but Picard too. My love for Jean-Luc is undimmed and he carried this very effectively. Some lovely shout-backs to NG, but its not pure nostalgia for the fans.

The Walking Dead – The first part of the season ended prematurely due to the pandemic – we only got the finale in October and now have to wait till next year for the second half. The series has come back strongly from quite a long slump, and whilst some of the regular gripes (apocalyptic battles which end up with only one peripheral character being killed, regular characters behaving with untypical stupidity to bring about some new peril, that sort of thing) are ever present, it’s back to being essential after a period where it was a mere duty watch.

Doctor Who – This year’s series was controversial amongst some Whovians, for seeming to change some of what we thought we knew about the Doctor’s origins. But did it? After all, our main source was the Master, who, as we know, lies… We will see. The Doctor did make a few appearances later in the year from her Judoon cell, to give us hopeful and inspiring messages about coping with lockdown isolation, which, I have to admit, brought a tear to my eye. She’ll be back on 1 January 2021, and let’s hope that the Tardis is a harbinger of hope for a better year ahead.

Some films watched on TV: Jurassic Park: Fallen Kingdom was perfect New Year’s Day fare. And the general stress of lockdown drew us to Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, and Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. The first I rather enjoyed – the script was just clever enough, with some neat historical references buried in amongst the improbable action. The second, well, once we had chuckled at the Bennett girls practising martial arts and strapping lethal weapons to their stockinged legs, it was slightly thin stuff. Last but not least in this category, the only superhero movie we watched this year, very unusually, was Deadpool, which was, to say the least, different… Very funny, very rude.

We’re saving up Agents of Shield (the last ever series) and Series 2 of His Dark Materials – some things to look forward to early in 2021.

We caught up with Modern Family, which we’d abandoned at the end of series 4, for no good reason. I found myself laughing loud and often. The characters don’t develop, not really, but when the writing and the performances are this good, there’s plenty of comic mileage to be had. We discovered Friday Night Dinner (only series 1 so far) which also made us laugh a lot.

The Good Place managed to be both very, very funny and profound. It made full use of its fantasy license, regularly wrongfooting us in ways that made us shout out something along the lines of WTF, and its final couple of episodes reduced me to real sobs, not just ‘something in my eye’ but full-on weeping. And yet, right up to the end, it was very, very funny too. A fabulous achievement.

We enjoyed the ebullient and charismatic Stuart Copeland in a couple of docs, his own Adventures in Music series, and his episode of Guitar, Drums, Bass (Lenny Kaye and Tina Weymouth represented the other instruments). We enjoyed the Lennon at 80 radio programme hosted by Sean Lennon, and a documentary about John and Yoko, Above Us Only Sky. The film Matanga/Maya/MIA was fascinating, though it left me somewhat dubious about her, not so much musically as politically. K T Tunstall presented an absolutely charming documentary about Ivor Cutler. A number of classical documentaries featured members of the remarkable Kanneh-Mason family: an Imagine programme, This House is Full of Music, Young, Gifted and Classical, focusing on cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason, who cropped up too in the excellent Black Classical Music, fronted by Lenny Henry and Suzie Klein, which introduced us to a number of composers we had not heard of previously. This last programme tied in with Black History Month, as did Gospel According to Mica, in which the singer explored the history of the genre through six songs, taking us from slavery days through the civil rights struggle to our own time. Soul America charted some of the same history, though taking a much narrower slice of history, broadly from the transmutation of gospel into soul, through the socially conscious sounds of the late 60s, to the sexual healing of the ’70s. Music, Money & Madness was a fascinating look at the background to Rainbow Bridge, the incoherent mess of a film that features Hendrix’s excellent 1970 gig in Maui, Hawaii.

Afua Hirsch presented African Renaissance (on African art), and co-presented with Samuel L Jackson the outstanding and at times overwhelming Enslaved. David Olusoga’s Africa Turns a Page put the spotlight on African writers, some familiar, others less so (see my books blog for some contemporary African fiction).

I Am Not Your Negro is an extraordinary film. It’s a 2016 documentary directed by Raoul Peck, based on an unfinished manuscript by James Baldwin. It explores the history of racism in the US through Baldwin’s reminiscences of civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King. Baldwin was one of the African American writers who I discovered in my teens and who inspired and challenged me. The film left me feeling quite shaken, such is the power of the images and Baldwin’s words.

France 1939: One Last Summer – A poignant compilation of home movies from France, from the summer of 1939. Impossible to see even the most carefree moments without the foreshadowing of what was to happen.

Confronting Holocaust Denial with David Baddiel was thoughtful, intelligent and impassioned.

On a somewhat (much) lighter note, Rome Unpacked was a lovely corollary to our recent visit, reminding us of how much we had yet to see (looking forward to our next trip, in the after-times…). I also fell somewhat (quite a bit) in love with Giorgio Locatelli. One quibble however – they visited the Jewish Ghetto and talked about the history of medieval antisemitism, without mentioning that the Ghetto’s inhabitants were deported and murdered by the Nazis in 1943. It’s not that I wanted the programme to delve into that in any detail – it just needed a one sentence coda to that section of the programme, rather than leaving the impression that murderous anti-semitism was something from the distant past.

A documentary about Nottingham Forest’s 1970s European Cup successes turned out to be a much more emotional experience than I’d been anticipating, when I caught sight of my lovely kid brother, who died in February, on one of the clips. He’d been a ball-boy at the first-round match against Liverpool in our 1979 Euro cup campaign, and was caught on camera at the end, clapping the team off the pitch and then punching the air in celebration. I sobbed for quite some time after that.

The Big Screen

2020 cinema began shortly after New Year, with Little Women. I knew what was coming, of course, having known the books for most of my life, but it didn’t stop Beth’s death being devastating, as I knew how soon I would be losing my little brother. I have the DVD but will need to brace myself before rewatching, particularly the bits where… well, if you’ve seen it, or any of the previous versions or read the book, you won’t need me to spell out the parts of the film which will break me on the rewatch. In fact, I won’t even say any more now, just refer you to Rick Burin’s review. Hell, it broke him, and as he says, ‘I’m northern and into football and stuff, but I just kept crying’.

And then a two-film day in mid-March, watching Celine Sciamma’s Girlhood (second time round for me) with Liz at the Showroom, and then in the afternoon Sciamma’s newest film, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, with Martyn. I loved both films, I found Girlhood just as powerful as I had the first time, with several moments that are firmly lodged in my mind, and Portrait definitely requires a re-watch. I wrote about both films for this year’s International Women’s Day blog but I’m going to send you to read Rick Burin again, as he reviews all of Sciamma’s films and much better than I can.

Note that the films I did see in 2020 totally kicked the Bechdel test‘s ass.

And that was it. No more cinema – they did reopen, of course, for a while, but as we have been super-cautious throughout the pandemic, we did not take advantage (I renewed my Showroom membership, as a gesture of support).

Can’t talk about cinema in 2020 without noting the tragically early death of Chadwick Boseman. I only knew him as Black Panther but that role alone was enough to imprint him on my consciousness – it was a performance of grace and power, as well as huge cultural significance. Will look out for chances to see Boseman’s other movies.

Previous years’ cultural highlights have included Opera North at Leeds Grand Theatre. Obviously, since March, the pandemic has put paid to that. In fact, I’d had to drop out before that – I could not attend the three productions in January/February as my brother’s condition worsened and I knew both that I needed to be available to see him whenever I could, and that I really couldn’t commit to producing a review in a reasonable timescale, or at all. I had no idea when I made that decision that my stint as an opera reviewer would have come to an end for the foreseeable future. I loved doing the reviews, and had a marvellous time seeing superb productions of works from Monteverdi to Britten and all points in between.

The move to on-line cultural activities, devastating as it was to the future of live performance, offered some delights. The Sheffield Classical Music Festival in May gave us access to some joyous and uplifting chamber music, as members of Ensemble 360 filmed performances in their gardens and living rooms. It was fabulous, even if it made us miss Music in the Round in the Crucible Studio even more.

Other online treats were Ian Dunt talking about being a liberal, David Olusoga talking about Black and British in Black History Month, Kit de Waal talking about My Name is Leon (all three talks part of Sheffield’s annual Off the Shelf festival), Sarah Churchwell and Bonnie Greer talking about the US election outcome (part of the national Being Human festival) – and two chances to hear and see someone who was an idol during my teenage years, the awesome and inspiring Angela Davis, first in her own South Bank lecture, and then in conversation with Jackie Kay (as part of Manchester Literary Festival). I might, theoretically, have got to the Off the Shelf events in normal circs. But I wouldn’t have made it to the South Bank, or the University of London, or even across the Pennines to Manchester.

But I long to get back to live chamber music and theatre at the Crucible, live opera at Leeds Grand Theatre, arty French movies at the Showroom and blockbusters at the IMAX… We’ll get there, thanks to the vaccine(s). And it will be so very lovely when we do. I may, just possibly, weep.

Screens, in general, have been our lifeline in the plague times. Not just the entertainment and enlightenment of what our television channels offer, but the Zoom/Messenger/Facetime link ups with the people we love, who we can’t be with. It’s not the same, obviously, and in the early days at least it made me feel, briefly, sadder once we’d waved goodbye and blown kisses to the small figures on our laptop screens. But our isolation has been less stark, less absolute, and at best those virtual encounters have made us feel hope, made us feel loved, given us the chance to support each other.

Refugee Week 2020 – Music in Exile

Posted by cathannabel in Music, Refugees on June 21, 2020

What better way to draw this series of Refugee Week blogs to a close than with music? Refugees have always carried the music of their home with them, wherever they have travelled, and treasured it, wherever they have settled. The richest and most beautiful music we can hear, from whatever tradition, has been nourished by the music brought in by those travellers, the songs that have sustained them through hardship, the melodies that remind them of home.

None of us knows what the next year will bring. The virus has both ignored borders, and reinforced them. It poses a threat to us all, but most seriously to those already vulnerable due to age, health and living conditions. Refugees and asylum seekers are and will continue to be amongst the most vulnerable. And whatever happens during the course of the year, for good or ill, there will still be refugees. There will still be wars and persecution and famine and terrorism, forcing people to leave home. There will still be camps full of people in transit, waiting for the chance to leave for a more stable life somewhere else. And there will still be fragile crafts launched on to the oceans, full of people hoping for landfall somewhere that they will find safety.

Last year, Opera North put on a production of Bohuslav Martinů‘s powerful and pertinent opera, The Greek Passion. Martinu was a Czech composer, who was working in Paris when the Nazis invaded his homeland, and then had to flee France for Spain and then Portugal, before settling in the US. The opera, written in the 1950s, tells of a village whose inhabitants are putting on their annual Passion Play, when the arrival of a group of refugees challenges their community, their values and their courage.

It is an opera about migration, about society’s rejection of the destitute and the desperate when they arrive at our gates for help, about the dangers of failing to challenge populist rhetoric, about the manipulation of society by those in authority. It’s also about compassion, humility and, ultimately, tragedy.

As the manager of a small inner city community project based in Leeds called Meeting Point, I work with refugees and asylum seekers every day and I find it quite extraordinary that an opera written all those years ago can be directly relevant to the day to day work that I do now, as well as the lived experience of thousands of individuals across the UK today.

Emma Crossley, Meeting Point

https://www.operanorth.co.uk/news/a-face-to-the-stranger-refugees-and-the-greek-passion/

Part of Opera North’s Lullaby Project, People’s Lullabies are performed by participants in the company’s Community Partnerships scheme, which works with local organisations to provide access to live opera and music for people who might otherwise encounter barriers to those experiences. The Refugees and Asylum Seekers’ Conversation Club at Mill Hill Chapel, Leeds, provides tea, coffee, healthy food, nappies, sanitary protection and toiletries to vulnerable families who have had to leave the countries they love because of war and persecution.

Soundroutes is an initiative that networks musicians of very different international backgrounds in new homelands. The Soundroutes project created the Soundroutes Band, with members from scattered new domiciles in Berlin, Brussels, and Rome. Shalan Alhamwy on violin, Alaa Zaitounah on oud, and drummer Tarek Al Faham are all from Syria, Papis “Peace” Diouf of Senegal is on guitar. The group mixes tracks of Arab tradition and African rhythms, but leaps out to free jazz. In a related combo, Peace Diouf rearranges and composes powerful traditional Senegalese grooves as jazz with Roberto Durante on piano and Hammond organ, Giancarlo Bianchetti on guitar, and drummer Moulaye Niang,

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/refugee-music-in-europe-migration-asylum-soundroutes-and-arab-jams

muziekpublique.be/artists/refugees-for-refugees

Music from Za’atari refugee camp:

With his brow furrowed in concentration, Abu Abdullah rhythmically strums his oud, exploring the core of a melancholic melody. Mohamad Isa Almaziodi’s robust and melismatic voice soars above, full of emotional ornamentation – sighing and repeating, rising and falling – until he runs out of breath and the phrase is forced to finish. In his song, Mohamad is singing about how strange life is, how harsh the nights are: ‘Oh this life is so strange… our home became very far. Very far.’ But before he can finish, he is overcome by homesickness and with his head in his hands, he cries. He is crying for his beloved country and for the father he left behind.

https://www.songlines.co.uk/explore/features/songs-of-the-syrian-refugees

The band Musicians in Exile is based in Glasgow, and is made up of refugees and asylum seekers.

Afshin Karimi is sitting in a circle of musicians, his eyes tightly closed as he taps his foot in time with the beat. He waits patiently for his moment, then opens his mouth and sings. Music is part of the reason that the 44-year-old Iranian singer and keyboardist found himself here, in a makeshift rehearsal room overlooking a busy Glasgow street, thousands of miles from home. He fled his country three years ago, not only because he feared persecution after changing his religion, but because the kind of music he was making was banned by authorities.

https://inews.co.uk/news/scotland/musicians-in-exile-meet-britains-most-unorthodox-band-made-up-of-asylum-seekers-and-refugees-299705

Ten Albums, Take 2

Posted by cathannabel in Music on May 12, 2020

I’ve done this ten album challenge thing before – in fact, about two years ago, in those dim and distant days before the plague came. The Facebook challenges are proliferating now, whilst we’re in lock down. I knew last time that I could have easily chosen an entirely different ten, equally compelling, equally influential, equally part of me, so this time round I did so. Thus, no Kirsty, no Bowie, no Crimson… But as I said last time:

Ten albums, from the thousands that have found their way on to our record player/CD player/cassette deck over the years. They’re weighted towards the 1970s, which I guess is inevitable. My teenage years, when my musical tastes were forming, freeing themselves both from parental influence and from the tribalism of my peers, trying things out and finding out what moved my feet, my hips, my mind and my heart. That process has never stopped, but it was at its most intense then. I carry with me the earliest music I heard – a kind of mash-up of the Goldberg Variations with E T Mensah & The Tempos, probably – and there was a gradual immersion in the world of pop and rock when we returned home from West Africa in the late 60s. All of those sounds are still part of my listening world, and I’ve added music from all around the world, and ‘classical’ music that my parents weren’t into (late 20th century stuff, and opera), and jazz and, well, a bit of everything really. And there’s a world of music out there that I don’t know, and that I might love if I get the chance to listen. So ten albums is daft and arbitrary but if you made it 100 albums it still wouldn’t be adequate.

I followed the rules on Facebook, posting just the album cover, without explanation. But here, I make the rules. So this is my ten album list, take 2, with a bit of a blather about the why, when and wherefore.

Bach – Goldberg Variations (harpischord). This is one of the earliest albums I remember hearing, whilst I was growing up in West Africa. I used to dance around the living room to it, so long as no one was watching. Years later, when we bought our own copy, selecting the Glenn Gould version(s), I wondered why it didn’t sound more familiar and it took me an embarrassingly long while to realise that the version I’d heard so many times as a child was played on harpsichord, not piano. Which version it was I cannot now tell. In my memory, the cover was green and gold. I don’t claim any kind of synaesthesia but I still hear Bach as green and gold (and Mozart as blue and silver).

So I don’t know who was playing the harpsichord on that album, but this Leonhardt chap is a possible contender – there are recordings from the late ’50s by him, and I imagine we took the record out with us to Ghana in 1960. I love this piece on piano too, obviously, but the harpsichord Goldberg is the piece that inspired my lifelong love of Bach and my lifelong exploration of classical music.

Ella Fitzgerald – The Cole Porter Songbook

Two birds with one stone here. Ella’s voice is sublime, and pairing her with Porter’s exquisitely crafted, delicious songs is perfection. And there’s the rub – I’ve had to defend Ella many times against the charge that, compared to Billie Holiday in particular, she’s just too perfect. Billie’s voice tells of betrayals and loss, a hard life, lived hard. And it’s wonderful, heartbreaking and vital. But the rich warmth of Ella’s voice is vital too. This is a 2 CD set, and is packed with fabulous songs. So in Love, Night and Day, Ev’rytime We Say Goodbye, I Get a Kick… And so many more. She lets the lyrics, those clever, subtle and often surprisingly rude, lyrics, work their own magic.

I’ve no idea when I first heard Ella, or Cole Porter, for that matter. I first heard some of Porter’s songs in the AIDS benefit project, Red Hot + Blue, which came out in 1990 – a very mixed bag, some of the artists very much of their time (The Thompson Twins, Jody Watley, Lisa Stansfield) but also Kirsty MacColl, Salif Keita, Neneh Cherry, k d lang… Other songs were already familiar, probably thanks to Sinatra. But if I had to pick one singer for Porter’s songs it would be Ella. She’s also done brilliant compilations of other great songwriters – Gershwin, Berlin, Kern. I don’t like all of her material, and whilst I admire her scat singing I don’t really enjoy it. Give her a tune though, and some genius lyrics, and she’s unbeatable.

Jimi Hendrix – Axis: Bold as Love

I have no idea why Jimi didn’t make it to Ten Albums, Take One. It’s almost as if he’s too obvious, has been too ubiquitous in my musical life, to be simply a name on a list. But there was a time before Jimi. I remember hearing on the news of his death in 1970 – I recall the crass, borderline racist dismissal of a ‘wild man of rock’ – and I know my brother had some of his albums, but it wasn’t until my musical life converged with my husband’s that I really started listening.

Axis: Bold as Love isn’t perfect. EXP is gimmicky and irritating, Wait till Tomorrow is enjoyable enough musically but the words are incredibly clunky and, yes, irritating. But when you’ve got Spanish Castle Magic, If Six was Nine, Castles Made of Sand, Bold as Love and Little Wing, you can forgive a couple of duff tracks.

There can’t be much Hendrix material I haven’t heard. Audience tapes of obscure gigs, demos and out takes and jams. Somewhere out there some collector is sitting on a recording I haven’t heard, another alternative version or another obscure gig, that might see the light one day. But meantime there’s a rich variety and abundance of material, given how short a time he had in the light. And I think it was with Axis: Bold as Love, that I properly fell for Jimi.

Jackson Five – Greatest Hits

Some might demur at the inclusion of Greatest Hits compilations in this account of the albums that influenced me. But (a) I make the rules, and (b) sometimes a well-chosen compilation is the way in to an artist’s work, a starting point. And when it comes to Motown, some of the actual albums contained a fair bit of ordinary, by the numbers material or ill-judged cover versions, whereas the Chartbusters collections and individual hits collections were all fab, no filler.

Motown was the soundtrack of my teens. I loved other stuff too, and Bowie was the most significant single artist, but those Motown songs, they still fill me with joy when I hear them now, just as they did back then. I loved the heartbreaky ones, obviously, the burning, yearning ones. But the Jackson Five produced some of the most purely joyous songs of their or any other time. ABC and I Want You Back are exhilarating, bewitching slices of pop/soul which sound as fresh now as they did back then. The interweaving of the voices – a Motown trademark of course, and with its roots in gospel – is uplifting and gives me goosebumps as only vocal harmonies can do.

I lent this album to a girl in our village, along with Michael Jackson’s debut solo album, Got to be There, and she moved away without giving them back. Not that I bear a grudge. OK, I did revile her name for many years but I’m over it now. Especially now we have another copy of the Greatest Hits.

Vaughan Williams – Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis/The Lark Ascending/Fantasia on Greensleeves

My mum loved VW. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know these pieces in particular, and I learned to love the music for myself. The two Fantasias fed into my growing interest in early music, as well as leading me to other VW compositions.

Somehow (and this may be linked to my mum too) VW evokes for me as no other composer does the English landscapes that I love best, the coastlines of Cornwall and North Yorkshire, the mountains of the Lake District, the hills of Derbyshire.

After my mum died, the Tallis became in my mind so powerfully associated with her, and my grief at losing her, that to this day (and she died 25 years ago this year) I cannot hear it without weeping. And less than three months ago, we buried my kid brother, and it was The Lark Ascending that played as we followed his coffin out of the church and to the graveside. I doubt I will ever hear that piece again without weeping either. But I will keep on listening to these pieces, because however much they remind me of loss, they also lift my heart up, let it soar with the lark.

King Sunny Ade – Juju Music

My first Ten Albums selection included the wonderful Osibisa, who brought back to me the sounds of highlife music that I’d heard in Ghana as a child. I’ve been exploring African music ever since, from all over the continent, but with a particular love of West African music.

Nigerian King Sunny Ade started off in highlife (which is Ghanaian in origin but which spread to Ghana’s neighbours over the course of the 20th century, and particularly in the era of independence). The music evolved and ‘juju music‘ drew on a wide range of influences (including funk and reggae), whilst retaining its Yoruban flavour.

This 1982 album was his major label debut but Ade had been releasing records for almost two decades by then. It’s one of the first big successes of what is often called (somewhat problematically) ‘world music’, and led to so many other great African musicians (Youssou N’dour, Salif Keita, the Bhundhu Boys, Ali Farka Toure and Ade’s compatriot Fela Kute, the king of Afrobeat) getting airplay and record sales worldwide. And it is gloriously infectious and rhythmically compelling and joyous.

Bela Bartok – 2nd Violin Concerto

Mrs Bolland was the Deputy Head at Queen Elizabeth’s Girls’ Grammar School and taught general Music classes, not to O or A level students but as part of a wider education, throughout my schooldays there. At some point, I think in the lower 6th form, she played us some really quite challenging music from the twentieth century – Schoenberg’s Verklarte Nacht, something by Roberto Gerhard which I cannot recall… and this. From the moment I heard the opening pizzicato notes and the soaring violin, I was entranced.

This was written in the late ’30s, when Bartok was deeply troubled by what was happening in Europe (he left his native Hungary in 1940 and never made it back home again – he died in 1945). As with so much of the very best music, there is darkness and light here, sorrow and hope. Hearing this gave me confidence to explore other ‘difficult’ twentieth-century music, a quest that has continued ever since. I owe Mrs Bolland a debt of thanks.

David Munrow – The Six Wives of Henry VIII

I loved the 1970 TV series, absolutely loved it. I went to some exhibition somewhere that had the costumes on display. I bought various tie-in publications to the series. I read everything I could about the Tudors (and have continued to do so over the years since).

And then there was the music. David Munrow and Christopher Hogwood founded the Early Music Consort in the late 1960s, and Munrow was in demand for soundtracking historical dramas with authentic music played on period instruments. He worked on The Six Wives, and its movie version, and on Elizabeth R. Listening to Vaughan Williams had prepared me for listening to Tudor music, and these pieces captivated me. At around the same time as I listened to this I acquired another album, presented as an Elizabethan Top Twenty. In fact, the ‘Elizabethan’ tag is a bit spurious as several pieces either pre- or post-date that era and although the performers were totally respectable there was the suggestion that the music was being just a little bit popped up to please audiences who wouldn’t normally go for this stuff . The Munrow set is more rigorously selected in terms of chronology, and because the performance of the music had to match the set, the costumes, all the period detail.

I recall being very shocked and upset to learn of Munrow’s suicide in 1976. But his legacy is remarkable – one can these days hear a fabulous range of early music on period or modern instruments in concert halls, on record and on the radio.

Miles Davis – Bitches Brew

We have Linda Buckley to thank for our introduction to Miles. To be honest, I didn’t really get Bitches Brew then, and if I had to recommend an entry point to Miles’ oeuvre, I don’t think it would be this (probs Kind of Blue, as predictable as that might seem). But I knew I was in the presence of musical greatness. We were into jazz rock at the time – Mahavishnu, Weather Report, Billy Cobham – and our way into jazz was through the jazz elements of that fusion. These days we listen to as much jazz as anything else. Miles played with anyone who was anyone, and his music changed dramatically over the years. So listening to all eras of Miles is a fantastic way to get into so many other artists, and to remain open to different strands of jazz, and to new bands and performers.

Radio 3 at the weekends gives us the chance to hear contemporary jazz on J to Z, which has introduced us to artists such as Dinosaur Junior, Tigran Hamasyan, Christian Scott Atunde Adjuah, Alina Bzhezhinska, Yazz Abmed, Kokoroko, Kamasi Washington… but also on Jazz Record Requests to hear the all-time greats. Now, I am not so fond of the trad stuff that a fair number of JRR aficionados seem to love. But there’s always something for us too – Coltrane, Ellington, Monk, Mingus, Haden, and, of course, Miles.

Simon and Garfunkel – Greatest Hits

I think this is the first album I bought. Or maybe the first one I bought from a record shop (my prized copy of Motown Chartbusters Vol. 3, on a remarkably solid slab of only slightly scratchy vinyl, was purchased at a knockdown price from a girl in my class). Bridge over Troubled Water was a huge chart hit, and my introduction to a world of wonderful songs.

The charts in 1970 were rich with hymn-like songs solemnly marking the passing of the 60s – not least the Beatles’ Let It Be – but Bridge Over Troubled Water was the blockbuster take: five minutes of booming, Phil Spector-inspired white gospel with a choirboy vocal and a simple, universal message beneath the sturm und drang. AP

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/apr/27/the-100-greatest-uk-no-1s

Just on this compilation, there’s For Emily, The Boxer, The Sound of Silence, I am a Rock, Scarborough Fair, America and of course BOTW.

Since then, I’ve listened to all the albums, and lots of much earlier S&G material, much of which is simply brilliant, and simply beautiful. And of course Paul Simon’s solo career (both alongside S&G and after the duo split), includes many, many gems: 1965’s A Church is Burning, Mother and Child Reunion, the Graceland album.

If I were to do this challenge again, next year, next month, tomorrow, I could find without great difficulty another ten albums that have influenced me significantly. Music has always been hugely important to me, and I’ve been listening for a very long time, to music from all eras, all genres, all continents. I have no truck with the ‘it’s all a bit shite nowadays’ school of thought – each era of music has had its share of tedious, derivative, witless and yet bizarrely successful material. Nor do I have any time for the wholesale dismissal of particular genres – I may not listen to a huge amount of country & western, for example, but I like quite a lot of it a lot (ditto rap). And in particular I’d hate to only listen to the music that is made here and in the USA, not when there are such extraordinary sounds emerging from so many other countries and cultures. The ten albums above have each led me in a particular musical direction, and for that – for these pieces of music and the artists who created them, for all the music I heard as a result and the joy it brought me – I am eternally grateful.

Postscript – Six Years of Singles

For a few years, it was the singles chart that dominated my musical life. Every Sunday we listened in, took notes, and voted, to come up with our own version of the chart. And every week we watched Top of the Pops (if the BBC changed which night that was on, I had to re-arrange my piano lessons to avoid a clash. No wonder my piano teacher/future mother in law did not try very hard to persuade me not to give up). That period, roughly between our return to the UK and my attempt to rapidly absorb and understand pop culture, and the point when music got a bit more ‘serious’ and album-focused was, say, 1968-1973. When I look back at the charts in those years there is an awful lot of absolute, utter, unadulterated tripe (some of which I remember with appalling clarity). But there are also some glorious slices of pop, and some formative moments.

1968 was the year I saw the Stones do Jumping Jack Flash on TOTP, the lighting making them look terribly sinister, and Arthur Brown doing Fire, wearing a hat that was actually on fire (no health & safety in them days). I think my mum was seriously shocked, and must have wondered whether her children should be exposed to this kind of thing. She didn’t ban it though, thankfully. I was shocked too, but in a good way. In total contrast, there was the sweet innocence of Mary Hopkin’s adaptation of an old Ukrainian folk tune, which both I and my mum could enjoy.

1969 introduced me to reggae via Desmond Dekker’s The Israelites. This was essential to my assimilation into school life. Music was very tribal and I never did get the hang of which group I might affiliate myself with most comfortably. I loved the music of both groups, was hopeless at conforming to dress codes or other social mores. But I did genuinely love ska, reggae, Motown and soul. Also this year, Jackson 5’s I Want you Back (see above), and Marvin Gaye’s version of Grapevine. And Tull’s Living in the Past, to nod to the other tribe.

1970 – Hendrix’s posthumous hit, Voodoo Child: Slight Return, probably the first Hendrix I heard (see above). And the first single I bought, Matthew’s Southern Comfort’s cover of Joni Mitchell’s Woodstock. That’s pretty cool as a first single, given how much I love Joni. Also one of the greatest singles ever, Freda Payne’s Band of Gold, which seemed to be always on the loudspeakers at the City Ground, and at Nottingham’s Goose Fair as we spun round on the waltzers.

Written by Motown brains trust Holland-Dozier-Holland, Band of Gold sees Payne sitting in a lonely bedroom, her wedding night gone disastrously unconsummated after some kind of freak-out by the groom. Although the exact details are tactfully veiled by Payne, it’s an unforgettably specific scenario, its horror hammered into your mind with that unyielding snare rhythm and told via a wondrous vocal line. BBT

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/apr/27/the-100-greatest-uk-no-1s

1971 and more reggae – Dave and Ansell Collins’ Double Barrel. My love of the A side, which sounded just as amazing when I reheard it a couple of years back, was only slightly dented by the B side being a bit of a rip-off.

If you wanted evidence of how far out, how unbound by the usual rules reggae was, you could find it at the top of the charts in early 1971: a piano line taken – sampled if you like – from Ramsey Lewis; a vocalist who largely grunted and bellowed incomprehensibly in the style of a Jamaican deejay: “I am the magnificent W-O-O-O!” It still sounds fantastic. AP

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/apr/27/the-100-greatest-uk-no-1s

Also, one of Diana Ross’s most gorgeous heartbreak songs, I’m Still Waiting. And while I never entirely loved T Rex, Jeepster was delicious.

In 1972, my French penfriend came to stay, and there was a bit of a cultural exchange as regards music. However, I think we won. Claude Francois and Michel Sardou couldn’t really compete with Alice (School’s Out) and Hawkwind (Silver Machine), T Rex (Children of the Revolution) and Deep Purple (Child in Time). There was also the uplifting loveliness of Johnny Nash’s I Can See Clearly Now.

1973 gave us Bowie’s Life on Mars – obviously not the start of my love affair with Bowie’s music, which really began when I heard Suffragette City on the juke box in the Cellar Bar, but a high, high point. Also this year, Lou Reed’s Perfect Day, a song that breaks my heart (when he sings, ‘You made me forget myself. I thought I was someone else, someone good’, oh lord). It’s a song about heroin, except that of course it isn’t, it’s a song about the fragility, the transience, the illusory nature of happiness. And then there’s the O’Jays’ Love Train, just to show that although my listening had shifted in a heavier direction, my love for soul had not (and never has since) faded.

After this period, we were less diligent in following the charts, and many of the albums we listened to in later years either didn’t yield singles, or those singles didn’t trouble the charts at all. And gradually we lost touch. The singles charts don’t mean today what they did back in the early ’70s, when one really could not face school on a Monday or the morning after TOTP unless one had listened/watched, and had an (acceptable) opinion on it all. But the art of the single – of packing a tune (with middle eight and memorable chorus), with lyrics that one could sing along to – into 2-3 minutes, with a B side that might even turn out to eclipse the actual hit – is, when it works, an extraordinary form of magic.

Albums of the decade

Posted by cathannabel in Music on December 30, 2019

Final list of the year/decade end. Honest.

Just ten albums, not ranked in order of importance or merit.

- Arctic Monkeys – AM

- Bjork – Utopia

- David Bowie – Black Star

- Alina Bzhezhinska Quartet – Inspiration

- Nick Cave – Skeleton Tree

- P J Harvey – Let England Shake

- Christian Scott – Ancestral Recall

- Songhoy Blues – Music in Exile