Refugee Week 2014 – Different pasts, shared future

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 15, 2014

Across the globe, as populations are dispersed by war, famine and persecution, as families are separated in the chaos, around half of those displaced are children. Over a thousand arrive in the UK every year, unaccompanied.

In Syria, in Iraq, in CAR, for example, families fleeing violence find themselves in transit with all of the accompanying hazards, or in camps where facilities are strained to the limit as people keep arriving. How can parents keep their children safe, fed, and physically healthy, let alone attend to their education, and their mental wellbeing? How can we, comfortable and safe as we are in comparison, imagine the choices that those parents have to make? How would we weigh the risks of remaining, against those of abandoning home and community? Could we, should we, send children to safety without us, as many parents in Europe did in 1938-9, knowing that we might never see them again, and not knowing what future they will face in a strange country?

And when they arrive in the UK, after whatever trials and hazards they have encountered on the journey, there are new difficulties to face. Our asylum system leaves many refugee families in destitution while their cases are considered, and parents are unable to work. They cannot choose where to settle, and so education and friendships are disrupted by frequent moves, as well as made more difficult by language and cultural barriers. And at any time, there may be a knock on the door, and a removal to detention, awaiting deportation back to the horrors that they fled.

Just a look through the papers over the last few days indicates what children in so many parts of the world are facing right now.

Vehicles crammed with men, woman and children who are fleeing the threat of violence, kidnapping and rape, were queuing at checkpoints at the frontier of Iraq’s Kurdish region yesterday. The refugees were among about half-a-million people who have fled their homes since Monday (Independent)

Thousands cross the southern U.S. border illegally each year in hopes of better lives. But now the problem has reached epic proportions, with children … fleeing the Central American countries of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala. And they are arriving in the United States alone — without a parent or guardian. (CNN)

Over a million Syrian refugees have arrived in Lebanon, fleeing the conflict in their country. Syrians now make up a quarter of the population of this tiny Mediterranean country. Many were forced to leave with only what they could carry, and are living in desperate poverty. Finding work is difficult, and many families are forced to send their children out to work to make ends meet. (Guardian)

The day after the army attack in Minova, 130 rape victims arrived at Masika’s displaced women’s camp. Seventeen of the girls were under 18. The youngest was 11. (Independent)

Meanwhile Unicef report that six months since intense fighting reached Central African Republic’s capital, Bangui, scores of children have been killed, hundreds have been maimed and thousands have been displaced.

The theme of Refugee Week 2014 is refugee children, ‘different pasts, shared future’. It’s also a shared responsibility. The reasons why people become refugees are many and various, but for the most part, they stem from adult actions which rebound most severely upon the smallest, the most vulnerable, the most helpless. So, over the next week I will be giving my blog space over to refugee stories, past and present, highlighting the work that’s being done by refugee organisations nationally and internationally – those who help refugees to survive, and those who help them to live once they have found a place of safety. Also check out my Refugee Week blogs from 2012 and 2013 via the archive.

Help for heroes

Posted by cathannabel in Football, Refugees on June 13, 2014

Launching this year’s Refugee Week with a contribution (suitably football related) from Nowt much to say’s excellent blog. More from me to follow.

I followed Iran during the 2006 World Cup in Germany. Working as a volunteer English tutor at the Refugee Education & Employment Programme in Sheffield, I’d recently met a lad from a Persian speaking part of Afghanistan that has close links to Iran. Me and Hossein (not his real name) chatted about life in Sheffield and football. He loved football and was supporting Iran in the World Cup. His eyes lit up when he recalled how the Iranians had beaten the USA in France ’98. “We win, we win…” he said punching the air. I tried to throw my own love of FC United of Manchester into our conversations but my English skills weren’t up to it. He preferred Liverpool when it came to English football.

I followed Iran during the 2006 World Cup in Germany. Working as a volunteer English tutor at the Refugee Education & Employment Programme in Sheffield, I’d recently met a lad from a Persian speaking part of Afghanistan that has close links to Iran. Me and Hossein (not his real name) chatted about life in Sheffield and football. He loved football and was supporting Iran in the World Cup. His eyes lit up when he recalled how the Iranians had beaten the USA in France ’98. “We win, we win…” he said punching the air. I tried to throw my own love of FC United of Manchester into our conversations but my English skills weren’t up to it. He preferred Liverpool when it came to English football.

REEP offered free English lessons to asylum seekers and refugees in the city and I was one of the volunteer tutors who worked on…

View original post 854 more words

Everyday Sexism

Posted by cathannabel in Feminism on May 28, 2014

I’ve been aware of the Everyday Sexism twitter account for some time, reading with anger and despair the seemingly endless reports of verbal and physical harassment, and of the host of ways in which women and girls are dismissed, disparaged and excluded. I thought things had, maybe, got a bit better during the course of the last forty-five years, since I became a teenager and realised that there were men out there who thought I existed in order to please them, and if I didn’t (either by being insufficiently attractive or by spurning their advances) then rather than being ignored I could expect to be insulted and threatened. It appears that little has actually changed.

I’m middle-aged now, past the age of invisibility, and so I don’t get catcalls any more – apart from the odd occasion when someone approaches in a vehicle from behind, and only realises as they draw level with me that they’ve just catcalled someone older than their mum… I do get shouted at sometimes when I’m out running, by people who think it’s hilarious to point out that I’m fat. I have been tempted to respond that whilst I know I’m fat, I’m clearly attempting to do something about it, and ask what they’re doing to address their own evident stupidity, but it’s early in the morning, no one else is around and I feel vulnerable. These things are idiotic, laughable, rather than hugely intimidating, but they anger me still. What makes someone think that because I am female and in a public place that they have the right to insult me, or to intrude on my thoughts?

I have never been the victim of violence of any kind, domestic, sexual or whatever. And yet I have to qualify that, because by the legal definition of sexual assault, of course I have. According to the law (not according to some deranged feminazi), sexual assault occurs when person A

- intentionally touches another person (B),

- the touching is sexual,

- B does not consent to the touching, and

- A does not reasonably believe that B consents.

I’d guess that any girl or woman who has ever been in a crowded pub or club could tick all of those boxes.

I can’t say I’ve been traumatised by my own experiences – I’ve been bloody annoyed by them, however, and at times unnerved and frightened. Even when there’s no physical contact, being shouted at in the street or from a passing car at the very least disturbs, as it’s meant to, and makes you feel more exposed and vulnerable. Cumulatively, these ‘minor’ incidents add to all the other ways in which we (women/girls) are told that our choices are irrelevant, that our bodies are not our own, and that our negative reactions to those messages are inappropriate, humourless, hysterical. And of course, I know plenty of women who’ve been on the receiving end of violence, and am certain that many more have been, but do not talk about it. If we call these experiences ‘everyday’ sexism, we’re not saying that all women experience these things every day, but that all women have experienced these things and, crucially, that they do not regard them as extraordinary.

I’ve never been told that I can’t do the jobs I want to do because I’m a woman. But I have been told that I’m too pushy, too strident, too aggressive. I have had men explain things to me about which I know far more than them, and I’ve spoken up in meetings only to be interrupted, or to have my contribution dismissed or totally ignored, and I’ve seen these things happening to other women in the workplace too. And, on the whole, I’d say I’ve had it pretty good. But many years working as a harassment officer, and as a manager with a predominantly female team of staff, have shown me what lots of women encounter. I’ve had to call men out on the toxic use of ‘banter’ to undermine women’s professional standing and their confidence, or the use of status to bully and demean women, or to pressurise women for sexual favours.

The nature of workplace harassment is that it often involves incidents which in isolation would seem minor and trivial, but which cumulatively have a serious effect on the recipient – this is recognised in harassment policies. The same is true in other contexts. The effect of once having someone shout at you in the street about what they want to do to you might be insignificant (assuming all they did was to shout) – the effect of this happening over and over again is to make you feel constantly insecure. When I was a young teenager, I remember initially feeling quite good about getting appreciative looks. Until I realised that the corollary of the appreciative look is that the looker may well feel that they have the right to do more than look – to comment (favourably or otherwise), to proposition, to touch, to grab, to threaten with rape. Within a very short period of time, the potential for receiving even the look as a compliment was massively diminished as I learned to quickly assess my safety, look for escape routes or potentially sympathetic bystanders.

None of that means that I want to ban men from looking at women. Any sensible and sensitive man, however, knows the difference between a look and a stare, between a look that encompasses a person and one that is riveted to a chest. Similarly with compliments – there are ways of saying you like the way someone looks that are OK. But sensible and sensitive men bear in mind that they have not been asked for their feedback, and that they have no automatic right to give it. They will realise that having given it, they do not then have the automatic right to follow it up and insist on a conversation that the woman may not wish to have, and they will be tuning into the woman’s response, to ensure they don’t intrude or offend. They not only won’t ignore a clear and unequivocal ‘no, I’m not interested’, they won’t pursue it unless the woman does give a clear and unequivocal signal that she wants to talk to them, and will accept it without argument and walk away if she changes her mind. And they will know that the fact that they have noticed a woman does not entitle them to tell her what is wrong with her body, her face or the way she is dressed. It’s really not that tough to get it right. Most men know this, and also recognise how daily interactions between men and women are messed up by the dickheads who don’t get any of this, and/or don’t care.

Whilst I’ve been writing this, two notable things have been happening. First of all, the #NotAllMen trope has been everywhere, initially as the all-too predictable response from so many male readers to women’s accounts of their own experiences, and then as the ironic riposte to that response, showing how it – intentionally or otherwise – derails and interrupts, making yet another conversation about men rather than about women. And the #YesAllWomen hashtag asserts that the more important fact is not that ‘not all men…’ but that ALL women experience everyday sexism, and ALL women are influenced as they go about their daily lives by the knowledge that SOME men represent a threat.

The other major development, of course, has been the Isla Vista shootings and the misogynistic (and racist) manifesto published by the killer. I don’t intend to weigh in with more analysis of this. I’m not qualified to diagnose his mental state from what I’ve read. I know that more of his victims were male than female, that some were stabbed rather than shot, which seems to complicate the simple narratives that emerged initially. But there’s no doubt that (a) his manifesto is overwhelmingly driven by a hatred of women – his hatred of men is linked to it, he wants revenge on men who have had more ‘success’ than he has with women, that (b) he was looking for women to attack and (c) three of his victims might be alive if he hadn’t been able to supply himself with guns and ammunition. It’s also clear that those who are trying to make him a hero, a ‘legend’, see him as someone fighting back against the bitches, the monstrous regiment of women. Sarah Ditum’s blog puts this well:

I know completely that not all misogynists are spree killers. It is self-evident that misogyny is a necessary but not sufficient condition for cases like this to occur, and that sufficiency must include the availability of weapons (a hammer will do) and the existence of particular psychological states. This is obvious. In fact, it is so obvious that I wonder why anyone would think it in any way complicates our understanding of Rodger’s motivation, because none of it alters the fact that misogyny exists and causes violence.

Not all misogynists kill. But all misogyny creates the conditions in which women are killed, raped and abused, and in which women fear being killed, raped or abused. This is not complicated. It is simple, it is deadly, and it is the reason feminism is necessary.

Not all dickheads are misogynists, but on the whole, men who like women, like them as people, recognise them as being human in exactly the same way they are, don’t behave like dickheads towards them. The men who represent a threat to us are the ones who don’t like women because they’re women, whether or not they are sexually attracted to them. Those who aren’t interested in women sexually and who don’t like them probably represent less of a threat to us in terms of violence but a considerable threat in terms of institutionalised sexism. Those who desire women sexually but do not recognise them as people are extremely dangerous, as the Isla Vista killings have reminded us (as if we needed it). One has only to read below the line on any article on any remotely feminist topic to be stunned by the venom directed at us, and how it is expressed in such highly sexualised terms.

The internet, which has allowed misogynists to vent their vileness at any woman who speaks out publicly, with anonymity and a potentially vast audience, may seem to be a threat. But it is also enabling us to support each other, to hear others’ voices and experiences, and to spread our challenges to sexist and misogynist views out to that same potentially vast audience. It’s scary to do so – just think of the kind of attacks that were meted out to Caroline Criado Perez who had the temerity to propose that a woman might feature on just one of our bank notes, or those who supported her campaign. But we can use it, and we must. And if the men who might be tempted to jump in with a ‘not all men’ instead focus on challenging the behaviour of those other men, the ones who catcall and grope and harass, the ones who belittle and dismiss and demean, the ones who hate women, then we really could start changing things. If the men who might be tempted to criticise our tactics and our priorities when we decide to speak out, back us up instead, then we really could start changing things.

Drawing attention to everyday sexism is not about embracing victimhood. Quite the reverse. We accept the status of victims when we keep quiet, internalise our fear and distress, blame ourselves for what others do to us – which we do for a host of reasons that are all too easy to understand. When we shout back, when we say out loud and in public, on our own behalf or in defence of others, THIS IS NOT OK, we reject victimhood, we become ourselves and take charge of our lives.

To quote Maya Angelou, who died today after a life of bearing witness and fulfilling her own ambition ‘not merely to survive, but to thrive; and to do so with some passion, some compassion, some humor, and some style’,

There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.

She also said that

You may not control all the events that happen to you, but you can decide not to be reduced by them.

To quote Laura Bates, ‘the thing about sexism is that it is an eminently solvable problem’. The first step, which is the focus of the project, is to force people to recognise that it’s a real problem. That recognition in itself could be a huge cultural shift. And if anyone thinks such huge cultural shifts don’t happen, or take generations, just think of civil partnerships/gay marriage. Ten years ago I would not have believed that such a change could come about in my lifetime, and the amazing thing is not just that these things are now enshrined in law, but that there has been so little fuss, so little outrage, and that most of what fuss and outrage there was has been perceived by most people as, more than anything, daft.

To redirect the flow of a river, you start by moving small stones. That’s what this project is about – small stones such as each individual testimony that appears on the website and on Twitter, each moment when someone challenges sexism in the workplace, the family, on the street.

We’re speaking out, we’re shouting back, we’re reaching out to each other, we’re choosing not to be victims, or bystanders. We’re saying that whilst these examples of sexism are ‘everyday’, they’re not normal, and they’re not OK. Everyday resistance, everyday solidarity.

@EverydaySexism

Laura Bates – Everyday Sexism (Simon & Schuster, 2014)

Unconsoled and unsettled

Posted by cathannabel in Literature on April 17, 2014

It’s rare that I finish a novel that I really haven’t enjoyed and find myself obsessed with it. That’s what’s happened, though, with Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled. This is a novel I was strongly recommended to read, and I can see why. I can recognise its beauty and brilliance. I can recognise the things it has in common with works that I love and revere – Butor’s L’Emploi du temps, for example, and W G Sebald’s Vertigo, or The Rings of Saturn.

But the experience of reading it – I so nearly gave up. It was as if I was trapped in one of my own anxiety dreams. Knowing I need to be somewhere, that I’m responsible for something, and finding that time and space are conspiring against me. From the start, the protagonist appears to know, vaguely, that he is here (wherever that is) in order to do something important, but not precisely what, when, or why. As in dreams, the relationship of the people he meets to him and to each other shifts and some who appear at the start to be strangers to him become in the course of the novel his father in law, wife and son. Other people from his past appear, incongruously, whilst his parents, expected throughout the course of the narrative, are never encountered at all. Even the common feature of such dreams that one is inappropriately (or not at all) dressed occurs as Ryder is swept off to undertake high-profile public engagements in his dressing gown (the inappropriateness appears to go unnoticed by everyone else). I read on with such reluctance, fearing that Ryder’s experiences would find their way into and would amplify my own nightly unsettledness – and they did.

It also tied in spookily well with my ongoing fascination with labyrinths and mazes. The city in which Ryder arrives, ahead of his concert, is one in which you could walk in circles indefinitely, as Ryder himself notes. He encounters dead ends – a street blocked off by a brick wall, with no way around it and no opening, but which lies between him and his destination. He is constantly getting lost, his journeys taking him seemingly very far from his destination, only for him to realise he has come back to his starting point. The novel traces ‘an odd, sepulchral, maze-like journey’, through a ‘deterring labyrinth’. But it’s not just a static labyrinth or maze, as baffling and disorienting as they can be, because space is constantly distorting itself, like Butor’s Bleston, which ‘grows and alters even while I explore it’ (Passing Time, pp. 182-3).

But it was only after I had, finally, finished the book that I remembered that I had, some months previously, lent it to someone else, someone who suffers from serious problems with short-term memory, and increasingly with anxiety associated with that condition, needing frequent reassurance as what happened even ten minutes ago is lost in fog. I had wondered idly at other times what impact this would have on her reading – and she does read, making good use of her local library – surely after a few pages she would have forgotten what she had just read, and have to go back again and again, so that she would never actually finish the book? But this book … as she read it, did she recognise her own anxieties in its pages?

It seems to me that living with that kind of memory loss must be like a waking anxiety dream. To have, throughout the day, that sense that you are missing something, that you should be doing something, that you should be somewhere, and to be unable to retrieve the information with any sense of certainty… If you write things down, how do you know for sure whether the writing is telling you that something will happen, or that something has happened? As events from the past float into your memory you have no way of anchoring them in chronology, they could have happened yesterday, or months ago. The gaps are troubling so you may fill them with explanations that start off as speculation but become fixed as you hang on to them for reassurance that you know what happened really. And whilst sometimes you are anxious and you know that the cause of the fear is that your memory is so poor, at other times you don’t remember that you can’t remember, and deny that you need help and can’t see why people keep reminding you of things.

I can’t see that I will want to re-read The Unconsoled any time soon. It simply troubles me too much, taps too accurately into my own anxieties and insecurities, and into the fog of memory loss that I witness second hand. But it’s brilliant, and it’s still in my head, weeks after I reached the final page.

The 96 – 7 minutes for 25 years

Posted by cathannabel in Football on April 12, 2014

As all this weekend’s football matches kick off seven minutes late, to commemorate the time that the semi-final between Forest and Liverpool at Hillsborough was called off, on 15 April 1989, and as the inquests into the deaths of 96 men, women and children proceed in Warrington, we seem to be within reach of truth and justice at last.

For so long, any time anyone tried to tell the real story of what happened – the failures in planning and organisation, the lies, the callous treatment of the bereaved – they were immediately countered with the narrative that was propagated so assiduously in the days after the tragedy, most notoriously by the Sun. It had become an accepted fact that the cause of the disaster was the behaviour of drunken, ticketless fans, arriving late and forcing their way into the ground, even when the Taylor report scotched so many of these cynical fabrications. Finally, with the report of the Independent Panel, and the overwhelming weight of evidence to vindicate the families’ and survivors’ accounts, that has irrevocably changed.

Too late for too many, and just too bloody late – how could it have taken so long for the truth that was known at the time, even as the events unfolded, to be brought back into the light?

I do not know how the families and survivors have sustained their fight for so long, and at what terrible cost. But I know that a sense of justice has driven them on. Of course they have been fighting for the people they loved who never came back from that football match, of course. But it isn’t just personal – it comes from a deeper sense of what is right, what is fair, and a refusal to let lies stand in place of truth. I was privileged to meet, very briefly, the father of one of the victims a couple of years ago, and what struck me most powerfully was his belief that the values that he held dear, and that he had passed on to his son, were being betrayed, in the vilification of the victims and the deliberate falsification of evidence, in the lack of respect for those who attended the match on that day, and those who loved them.

I am indebted to Gerry, from the wonderful That’s How the Light Get’s In blog, for finding this very apt quotation from Dickens’ Old Curiosity Shop:

the world would do well to reflect, that injustice is in itself, to every generous and properly constituted mind, an injury, of all others the most insufferable, the most torturing, and the most hard to bear; and that many clear consciences have gone to their account elsewhere, and many sound hearts have broken, because of this very reason; the knowledge of their own deserts only aggravating their sufferings, and rendering them the less endurable.

They have, nonetheless, endured. And the seven minute delay and the 96 empty seats remind us again of what was lost, as the inquest testimonies remind us that each of the 96 had names, stories, hopes and aspirations, and people who loved them.

They’re not alone, they haven’t walked alone, they never will.

RIP the 96

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-26765007

https://cathannabel.wordpress.com/2012/04/14/15-april-1989/

https://cathannabel.wordpress.com/2012/09/12/15-april-1989-finally-the-truth-now-for-justice/

Rwanda: remember – unite – renew

Posted by cathannabel in Genocide on April 5, 2014

It’s twenty years since we all blinked and failed to notice that hundreds of thousands of people were being hacked to death in a small country in Africa. Twenty years since we decided that the appropriate response to machete-wielding mobs on the streets, targeting anyone whose ID card gave the wrong ethnic origin, was to withdraw almost all the peace-keeping forces stationed there, and tell the rest they could not intervene. Twenty years since we waffled and fudged about ‘acts of genocide’ and muddled up Hutus and Tutsis, and showered emergency aid on killers, and muttered about tribalism, and ‘six of one…’.

There are all sorts of excuses. The failed intervention in Somalia, the joyous distraction of the South African elections (for once, a good news story from Africa), and the general reluctance to commit troops and risk ‘our’ people’s lives in such a messy, chaotic and volatile situation. But it is inescapable that part of the reason that we didn’t stop it happening was because of where it was happening. Because, as Francois Mitterand actually said, more or less, in Africa massacres aren’t such a big deal.

In many ways, genocides resemble one another more than they differ from each other. If we discount scale, as we must, since it is the intention to wipe out a race/group/community rather than the numbers involved, or the degree of success in that endeavour that defines genocide, there is a common trajectory that we can trace. The group marked for destruction must be isolated, vilified, made objects of fear as well as hatred. They may be identified as less than human – vermin, lice, cockroaches – since no one baulks at the death of such creatures. They must be classified, marked, labelled, listed, so that they can be tracked down. And once the killing starts, for the group marked for destruction there is the desperate search for safety, for shelter and protection, the knowledge that each person you encounter may denounce or protect you. Not only that, but the threat to those who did try to help that they too, and their families, would die if they were exposed. In fact, merely refraining from murder may be an act of resistance likely to be punished with death.

There are things about Rwanda however, that are different. Firstly, the sheer speed of the events that engulfed that small country in Africa is staggering. There had been decades of sporadic massacres, which is why a Tutsi rebel army, composed mainly of refugees and children of refugees, was in the process of invading the country. And preparations had certainly been laid well in advance, lists drawn up and machetes stockpiled. But still, from the trigger of the shooting down of the President’s plane to the RPF victory only four months elapsed. Four months, and 800,000 people dead. Many more maimed, raped, traumatised, orphaned. So much destruction in such a short time. A tsunami of brutality, when everything was irrevocably changed in moments.

There was no great machinery of bureaucracy to process the destruction of the Tutsi, who were killed, for the most part, by their own neighbours, or by the militia on the roadblocks who simply needed to ask for their ID to know whether they should die. There were no camps set up to process those captured and marked for death, just places where people sought refuge and instead found that their hoped-for sanctuary was in fact a trap where the killers waited until they were gathered together, before sweeping in to destroy. There was not even the pretence of any fate for the Tutsi other than death.

And because of the speed, and because the victims, like their murderers, were in many cases rural people, not highly educated and literate, and if they hid it was in the bush, there is no Anne Frank, no Helene Berr from Rwanda, both murdered, but who left records of what it was like to have to hide, to live in fear, to be marked for death. The narratives of Rwanda are those of the survivors. Whole clans were wiped out, so that now it is as if, as a survivor put it, a page in the album of humanity has been torn out, and of many of those families and individuals there may be virtually no trace remaining. After all, that’s what genocide aims to do. It’s never enough to kill all the people, you have to kill their history, their culture.

But that’s one of the odd things about the Rwandan genocide. The Hutu and Tutsi peoples were not distinguishable from each other by a language – even an accent – or a religion. They were – supposedly – different in physique, but in reality decades of intermarriage meant that one could not actually identify anyone reliably in this way. The mythology of their enmity was fostered by successive colonial governments, who favoured first one group and then the other, exploiting the tensions that this created. The different names existed, certainly, but the identities were not fixed. Because Hutu and Tutsi were associated with different modes of life, if your circumstances or occupation changed, your ‘ethnic’ identity could change too. It was the colonial governments who put in place the system of identity cards that stated which group one belonged to, and made that identity fixed and inescapable.

Many, many ordinary people did extraordinary things to protect friends, neighbours or total strangers. And many of those who were there in an official capacity broke ranks to do what they could. Major Stefan Stec, with the UN Peacekeepers, faced down militia at the Hotel Mille Collines, attempting to evacuate some of the many Tutsi and moderate Hutu who had taken refuge there. He was so tormented by the events he witnessed, by his own sense of failure, and by the harsh judgement of many who weren’t there and had no choices to make, on the inadequacy of the UNAMIR response, that he died eleven years later, as a result of PTSD. Romeo Dallaire, who commanded those forces, suffers similarly, and attempted suicide six years after the genocide. And Mbaye Diagne, a Senegalese UN military observer, ferried people through roadblocks to the Mille Collines, bluffing and bribing his way past the militia until he was killed in a mortar attack in May 1994.

Yolande Mukagasana’s world changed on 6 April 1994. Within days she had seen her husband killed. She had lost contact with her children. She had come close to death, and had seen people who she, as a nurse, had healed, ready to kill her or hand her over to be killed. She also encountered people who owed her nothing and yet who kept her safe, just because it was the right thing to do. She was tormented first by not knowing her children’s fate, and then by knowing it. Once safe, she threw herself into her old role of healer, but her own healing took a long time – to the simple guilt of having survived when so many didn’t, she added the guilt of having survived when her own children didn’t, and of knowing that others had died for refusing to hand her over, or because they were mistaken for her. She drew orphaned and lost children to her, and started an organisation called Nyamirambo Point d’appui, named after the area of Kigali where she lived with her family, and where she saw her neighbours become murderers. She started to rebuild, there, where she’d lost everything.

Yolande writes ‘contre l’oubli’, so that the dead aren’t entirely lost, so that the truth isn’t buried with them. And that includes uncomfortable truths about the role of international bodies, and most particularly of the French government, both actively and passively enabling the genocide.

But this duty of memory is not just for the past, but for the future. Surely if we remember what happened twenty years ago in that small African country, as we remember what happened over seventy years ago in Nazi occupied Europe, what happened almost forty years ago in Cambodia, we will see the signs next time before it’s too late? We will make the right choice about whether and when to intervene?

Click to access Mukagasana.pdf

http://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/AMINAMukagasana.html

Yolande Mukagasana – N’aie pas peur de savoir (Robert Laffont, 1999)

Rwanda pour memoire, Samba Felix N’Diaye (L’Afrique se filme, DVD, 2001-2003)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/special/2014/newsspec_6954/index.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacqueline_Mukansonera

http://www.freemedia.at/awards/andre-sibomana.html

http://www.hmd.org.uk/news/remembering-rwanda-%E2%80%93-20-years

- Dallaire, Roméo (2005). Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0-09-947893-5.

- Des Forges, Alison (1999). Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda (Report). New York, NY: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 1-56432-171-1.

- Gourevitch, Philip (2000). We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families (Reprint ed.). London; New York, N.Y.: Picador. ISBN 978-0-330-37120-9.

- Melvern, Linda (2000). A people betrayed: the role of the West in Rwanda’s genocide (8, illustrated, reprint ed.). London; New York, N.Y.: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-85649-831-9.

- Melvern, Linda (2004). Conspiracy to Murder: The Rwandan Genocide. London and New York, NY: Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-588-2.

- Prunier, Gérard (1998). The Rwanda Crisis, 1959–1994: History of a Genocide (2nd ed.). London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-372-1.

- Prunier, Gérard (1999). The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide (2nd ed.). Kampala: Fountain Publishers Limited. ISBN 978-9970-02-089-8.

Butor at Belle Vue

Posted by cathannabel in Events, Michel Butor on March 8, 2014

The long history of Belle Vue Gardens in Manchester is being celebrated this month, and it seems timely to note its appearance, under the name of Pleasance Gardens, in Michel Butor’s Manchester-inspired 1956 novel L’Emploi du temps (Passing Time).

Butor’s view of Manchester (Bleston in the novel) was, it must be admitted, largely negative. He loathed the climate, and the food, and seems to have been deeply unhappy in the city, where he arrived to take up the post of lecteur in the French department at the University in 1952.

He seems to have taken to Belle Vue, however. Pleasance Gardens, along with the various peripatetic fairs which rotated around the periphery of the city, on the areas of waste land, represent a mobile and open element in a closed, even carceral city, and a window on different kinds of community than those indigenous to Bleston. The narrator sees the friends he knows in a different light in these places, which may be in Bleston but are not fully part of it and don’t share its malaise.

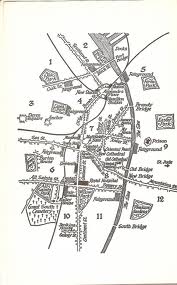

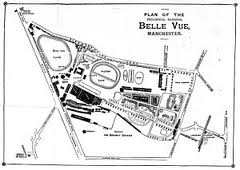

Pleasance Gardens appears on the frontispiece map, in the bottom left-hand corner, its shape not dissimilar to that of the real Belle Vue. Butor took from the real city of Manchester the geography and architecture that interested him and that fitted with his narrative preoccupations, and ignored or altered the rest. The descriptions include a great deal of precision and detail – however, the historians of Belle Vue will have to judge where the fictional version departs from its model.

He describes the entrance to the Gardens:

The monumental entrance-gates whose two square towers, adorned with grimy stucco, are crowned … with two enormous yellow half-moons fixed to lightning conductors, and are joined by two iron rods bearing an inscription in red-painted letters beaded with electric bulbs then gleaming softly pink: ‘Pleasance Gardens’.

The big folding door which is armoured as if to protect a safe, and only opens on great occasions and for important processions, whereas we, the daily crowd, have to make our way in by one of the six wicket-gates on the right (those on the left are for the way out) with their turnstiles and ticket collectors’

The earthenware topped table which displayed, on a larger scale and in greater detail, with fresh colours and crude lettering, that green quarter circle with its apex pointing towards the town centre…

The tickets themselves are described in detail:

the slip of grey cardboard covered with printed lettering: On one side in tall capitals PLEASANCE GARDENS, and then in smaller letters: Valid for one visitor, Sunday, December 2nd. And on the other side: REMEMBER that this garden is intended for recreation, not for disorderly behaviour; please keep your dignity in all circumstances’

On this winter visit:

There was scarcely anybody in the big, cheap restaurants or in the billiard-rooms; avenues, all round, bore black and white arrows directing one to the bear-pit, the stadium, the switch-back, the aviaries, the exit and the monkey-house.

We walked in silence past roundabouts with metal aeroplanes and wooden horses, … and past the station for the miniature railway where three children sat shivering in an open truck waiting to start; and past the lake, which was empty because its concrete bottom was being cleaned’.

Posters everywhere echoed: ‘Come back for the New Year, come and see the fireworks’.

A later visit, in summer, followed one of the fires that feature so frequently in the novel. Belle Vue was devastated by fire in 1958, and whether this account was inspired by a real event I do not know – it may well be that whilst Manchester was plagued by an unusually large number of arson attacks over the period that Butor was there, he extrapolated from that to a fire at Pleasance Gardens, purely for narrative purposes.

In the open air cafe that is set up there in summer in the middle of the zoological section, among the wolves’ and foxes’ cages and the ragged-winged cranes’ enclosure, the duck-ponds and the seals’ basins with their white-painted concrete islands. I could see, above the stationary booths of this mammoth fairground, eerily outlined in the faint luminous haze, the tops of the calcined posts of the Scenic Railway, with a few beams still fixed to them like gibbets or like the branch-stumps that project from the peeled trunks of trees struck by lightning; and I listened to the noise of the demolition-workers’ axes’

If Butor generally warmed to the Gardens, his portrayal of the animals in the Zoo is less enthusiastic – he speaks of the cries of the animals and birds mingling with the noise of demolition, of melancholy zebras and wretched wild beasts, and of their howls during the firework display. Perhaps their imprisonment chimed uncomfortably with his own sense of being trapped in the city.

http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/nostalgia/way-were-belle-vue—1209695

Time to Talk

Posted by cathannabel in Personal on February 6, 2014

I’m supporting this campaign by Rethink, to encourage people to talk about mental health. Because it’s hard to speak about it publicly, because there is a stigma attached to mental illness which does not apply to most physical illnesses, because it feels like a weakness, because you think you’re the only one, because you’re afraid (of what you’re experiencing, and of how other people will react).

I wish I could say that ‘coming out’ in this context is always met with outpourings of support and love and help. There’s a lot of that.

But there’s also – telling your boss you’re having treatment (medication and counselling) for depression, and her (a) telling other colleagues to keep an eye on you, (b) telling the management board that you have mental health problems and (c) generally treating you from there on in as a problem, not a colleague who’s having a problem. That was about ten years back – would it be different now? It depends on the workplace, on the boss. It’s risky, and if now I would (and do) say things publicly it’s because in the time since that dark episode I’ve gained in strength and confidence and because what happened to me then made me angry and determined to challenge those attitudes.

Of course there’s also the whole ‘pull yourself together’ thing that will surface, explicitly or implicitly. Especially if your life circumstances don’t ‘justify’ your depression. If bad things have happened to you, and your illness seems to be a result of that, the sympathy will probably be more straightforward. If your life is outwardly fine, then some people – including kind, loving people – will feel that you should be able to sort yourself out.

But a lot of the stuff that deters one from talking openly is internal, not external. No one told me I didn’t have a right to feel depressed because I was physically healthy, employed, solvent and had people who loved me. I told myself that. No one told me I was a failure and a mess, because, since I left the house every day washed, appropriately dressed and apparently functioning, only I knew (for the most part) that I was a failure and a mess. No one told me I couldn’t be really depressed because I kept leaving the house every day washed appropriately dressed and apparently functioning – that was me, telling myself that – as I read account after account of depression, hoping to see myself in there – I obviously didn’t have a serious problem and should be able to sort myself out.

How do you measure the seriousness of depression? I was never hospitalised, I had very little time off work, I was never unable to get up and go through the motions of life. But for a long time I had that nasty little mantra in my mind throughout my conscious day and every time I woke during the night, and for a long time I only smiled when people could see me. For a long time I saw my life as trudging on, up hill all the way, fog and gloom all around me so that I couldn’t see where I was heading, or even see that I wasn’t alone on the path. I wrote a poem along those lines, a very bad poem, long since deleted, but at the time it helped to write it down. People who didn’t know me really well didn’t know – but they sensed something, or perhaps the lack of something, a spark . I had a few job interviews during this period and the feedback suggested a lack of enthusiasm or interest in the post, a lack of dynamism and energy.

Partly, you realise how bad it’s been when it starts to get better. When the mantra stopped. When my smile stayed on my face after I’d shut the door, when no one but me was there. When the fog cleared and I could see that however far I still had to trudge on uphill there was a beautiful view from where I was, and there were people alongside me.

I’m talking about this now – more publicly than I ever have before – because I’m prompted by the Rethink campaign to share my story. And because I know that some people who know me will be surprised, and may think I’m ‘not the type’, but may therefore rethink their assumptions. As you look around you, in a lecture or a meeting, at a party or a gig, there will be people there, talking and laughing and making decisions and relating to those around them, who are or have been in the grip of depression or anxiety, who are struggling with or have struggled with obsessive compulsive behaviour or eating disorders, who are experiencing or have known the intense highs and lows of bipolar disorder. You’ll never know, unless they dare to share it with you.

It’s a part of me, I think, that propensity to slip into the pit. I stay out of it mainly by being busy enough, with lots of things I care about and that bring me joy, but not so busy that I succumb to anxiety and sleepless nights and feelings of panic. I know the signs now, and can usually take preventative steps before I start to slip. Once you’re in there, it’s hard to get out, as Alyssa Day’s blog vividly and powerfully describes.

It shouldn’t be so hard to talk about this stuff. It is, still, and I will press Publish on this post with more trepidation than for anything else I’ve sent out into the blogosphere.

But it really is time to talk.

http://alyssaday.blogspot.co.uk/2014/01/on-one-writer-and-depression-aka-life.html?m=1

http://www.rethink.org/?utm_source=email&utm_medium=informz&utm_campaign=blank

Journeys – Holocaust Memorial Day 2014

Posted by cathannabel in French 20th century history, Genocide, Second World War on January 26, 2014

The journey that we most associate with the Holocaust is the one that ends at those gates.

Our imagination cannot go beyond that point, no matter how many accounts we read from those who survived. Our imagination baulks at the journey to the gates, not just at its ending – the cattle trucks from all corners of occupied Europe filled with people who not so long before had lives, loves, professions and occupations, and had all of those things gradually stripped from them till all that was left was a name on a list.

But for many of those individuals, the Holocaust journey began long before the cattle truck to Auschwitz. The Plus qu’un nom dans une liste project has put together many stories of individuals and families deported from France, and I’ve selected just a couple, to show what happened to them once their homes were no longer safe for them.

The Taussig family left Vienna in June 1939, having obtained a ‘Reisepass’, and left Reich territory the same month via the frontier post of Arnoldstein in Carinthia, where nowadays the three borders of Austria, Italy and Slovenia meet. Rudolf and his wife Leonie, both 56, and their son Hans, 29, crossed into Italy through the Friuli province.

Italy had stopped allowing foreign Jews into its territory by this time, and the authorities probably escorted the family to the Italian Riviera. On 9 July the Taussigs arrived at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin on the Cote d’Azur. The gendarmes had been alerted by phone that a group of refugees were waiting on the beach for the people to whom they’d paid money for safe passage, and arrested them and took them to Menton.

Those arrested that night were:

- Léonie Taussig, born 29/3/1885 in Vienna; daughter of Joseph Bondy and Bertha Donath

- Rudolf Taussig, born 26/5/1883 in Chrudim, Czechoslovakia, son of Adolf Taussig and Louisette Teveles

- Hans Taussig, born 28/6/1910 in Vienna, son of Rudolf and Léonie

- James Landau, born 21/08/1895 in Breslau, son of Wilhem and Henriette Kehlmann

- Bruno Kulka, born 30/12/1894 in Prerou (Moravia), son of Jean and Emma Herzka.

On 11 July Rudolf and family were transferred to Lyon, where he and Hans were interned. Rudolf was freed in January 1940, and Hans on 21 February. On 23 April 1940 Rudolf obtained a refugee worker permit for work as a metallurgist which was extended till 15 July 1941. However, the tribunal in Nice judged them in their absence for having entered France illegally, and condemned them to a month in prison and a fine of 100 francs. Rudolf and Hans served their sentence at the prison St Paul de Lyon and were freed in September 1941. They requested emigration to the USA, where their daughter Alice had already settled – she and her husband had managed to leave France for Portugal, where they got a visa in Lisbon in March 1940.

The Taussig family were arrested during the round-ups in the southern zone in the summer of 1942, interned at Drancy and all three deported to Auschwitz in September 1942 on convoy 27.

The Taussigs’ journey – Vienna to Arnoldstein to Friuli to Roquebrune Cap Martin to Menton to Lyon to Drancy to Auschwitz

Gisela Spira fled Berlin early in 1939 with her mother and elder sister Toni. The three women arrived in Brussels on 31 January, where father Herzel and brother Siegmund were already waiting for them. The youngest brother, Felix, had already been placed by the Comité d’Assistance at the house of the curate of Wezembeek, east of Brussels.

After May 1940, round-ups of German and Austrians in Belgium as enemy aliens prompted the Spira family to go into exile again, and they crossed clandestinely into France. They were interned there almost immediately, at Bram, in the Aude. They were freed on 30 June, and found somewhere to live in Salleles d’Aude, where Gisela met Bertold Linder, ten years older than her, who she married in January 1942.

On 26 August 1942, the Spira family was arrested, apart from Siegmund and Gisela who had moved to Lamalou les Bains, and then to St Martin Vésubie, near the Italian border. Herzel, Rosa, Toni and Felix were deported on Convoy 31 to Auschwitz where they were murdered.

On 25 December 1942, Gisela gave birth to a son, Roland.

Hundreds of Jewish refugees had been forced to settle in St Martin by the Italian administration. Many tried to cross the mountains, hoping to meet up with the Allied army. In August/September 1943, a new danger appeared, as the Wehrmacht occupied the old Italian zone, and on the 10th, the Gestapo arrived in Nice.

At St Martin, the local refugee organisations told families to pack their suitcases as quickly as possible, and to follow the retreating Italian army. Siegmund, Frieda and Roland, and around 1,200 men, women and children then tried to escape across the Alps, a biblical exodus which took place between 9 and 13 September. 328 people were intercepted and escorted to the Borgo San Dalmazzo camp in Italy, under the guard of Italian soldiers until the SS arrived. Two months later, on 21 November, the camp was evacuated, and its inhabitants transported to Nice, where they were interrogated by the Gestapo.

Gisela, her son, brother and husband were deported from Nice to Drancy. On 7 December 1943, they left Drancy on Convoy 64. On 12 December, 13 days after Roland’s first birthday, on disembarking from the cattle trucks, Gisela and her son were gassed at Auschwitz.

Siegmund alone survived. His journey continued from Auschwitz to Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated. He settled in the USA.

Gisela’s journey – Berlin to Brussels to Bram to Salleles d’Aude to Lamalou les Bains to Saint Martin Vesubie to Borgo San Dalmazzo to Nice to Drancy to Auschwitz

What’s striking is not just how those journeys ended – it’s that process of seeking safety, finding it illusory, moving on in the hopes that the next place will be different. Taking their old lives with them as they went from one apparent haven to the next. In any of the convoys from Drancy there would be those who had sought refuge in France from persecution over the previous half-century from all over Europe, and those whose families had lived in France for generations. There would be workers and bosses, Communists and conservatives, believers and non-believers. Some of their journeys were long and convoluted, like those outlined above, with many apparent reprieves along the way until that final denial of their right to live. Others had been rounded up on French streets where they had spent all their lives, and like Helene Berr, made only a short journey from Paris to Drancy before the terrible journey from Drancy to annihilation.

Those who destroyed them saw them as one thing only. That’s the nature of genocide, nothing matters except that one defining characteristic – you are a Jew, a Tutsi, and therefore you have to die. That’s why we have to make them, wherever we can, more than a name on a list. Gisela Spira, Rudolf Taussig, Helene Berr, deserve their own stories, so that we glimpse the people they were, the people they might have been.

And if we can enter imaginatively into their journeys, can we not also think of them when we hear of those in our own time who are driven from their homes by war and persecution, seeking safety where they can and often finding further perils instead?

Transformation of Sounds

Posted by cathannabel in Genocide, Music, Second World War, W G Sebald on January 25, 2014

W G Sebald describes, in his extraordinary novel Austerlitz, a recording of a film made at the Terezin concentration camp, as part of the effort to present it as a humane and civilised place to visitors from the Red Cross (overcrowding in the camp was reduced before the visit by wholesale deportations to Auschwitz, and once the visitors had left, remaining inmates were summarily despatched too).

In Austerlitz’s search for a glimpse of his mother, who had been interned there before her death, he slows the film down to give him a greater chance of spotting her fleeting image. This creates many strange effects, the inmates now move wearily, not quite touching the ground, blurring and dissolving. But:

‘Strangest of all, however, said Austerlitz, was the transformation of sounds in this slow motion version. In a brief sequence at the very beginning, … the merry polka by some Austrian operetta composer on the soundtrack … had become a funeral march dragging along at a grotesquely sluggish pace, and the rest of the musical pieces accompanying the film, among which I could identify only the can-can from La Vie Parisienne and the scherzo from Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, also moved in a kind of subterranean world, through the most nightmarish depths, said Austerlitz, to which no human voice has ever descended’. (Austerlitz, pp. 348-9)

The deception that the film sought to achieve is exposed.

The association between Terezin and music has another dimension, however. A remarkable number of inmates were Czech composers, musicians and conductors, and this, combined with the Nazi attempt to make the camp appear to be a model community with a rich cultural life, gave opportunities for music to be created and performed here. There is no easy comfort in this fact, when one knows that most of those who played, composed and conducted died here, or at Auschwitz, and that the moments of escape into this other world were few, and may in some ways have made the contrast with the brutality and barbarism of the regime even harder to bear.

The music of Terezin, however, now reaches new audiences through performance and recordings. Each time we hear the voices of those the Nazis sought to silence, that is a small victory.

Czech conductor Rafael Schachter – transported to Terezin in 1941, organised a performance of Smetana’s The Bartered Bride and finally of Verdi’s Requiem, performed for the last time just a few weeks before his transfer to Auschwitz in October 1944

Jazz musician and arranger Fritz Weiss – arrived in Terezin in 1941, set up a dixieland band called the Ghetto Swingers. Fritz was sent to Auschwitz in 1944, with his father, and was killed there on his 25th birthday.

Viktor Ullmann – Silesian/Austrian composer, pupil of Schoenberg, was transported to Terezin in 1942. He composed many works there, all but thirteen of which have been lost, before being transported to Auschwitz in 1944, where he was killed.

Gideon Klein – Czech pianist and composer, who like Ullmann composed many works in the camp as well as performing regularly in recitals. Just after completing his final string trio, he was sent to Auschwitz and from there to Furstengrube, where he died during the liquidation of the camp.

Pavel Haas – Czech composer, exponent of Janacek’s school of composition, who used elements of folk and jazz in his work. He was transferred to Auschwitz after the propaganda film was completed, and was murdered there.

Hans Krasa wrote the children’s opera Brundibar in 1938, and it was first performed in the Jewish orphanage in Prague. After Krasa and many of his cast were sent to Terezin, he reconstructed the score from memory, and the opera was performed there regularly, culminating in a performance for the propaganda film. Krasa and his performers were sent to Auschwitz as soon as the filming was finished, and were gassed there.

Not all of the musicians of Terezin were killed. Alice Herz-Sommer survived, along with her son. Now 110, Alice sees life as miraculous and beautiful, she has chosen hope over hate.

“The world is wonderful, it’s full of beauty and full of miracles. Our brain, the memory, how does it work? Not to speak of art and music … It is a miracle.”

http://www.terezinmusic.org/mission-history.html

http://www.theguardian.com/music/video/2013/apr/04/holocaust-music-terezin-camp-video

http://holocaustmusic.ort.org/places/theresienstadt/

http://www.theguardian.com/music/2006/dec/13/classicalmusicandopera.secondworldwar

http://www.haaretz.com/weekend/week-s-end/i-look-at-the-good-1.261878

http://claude.torres1.perso.sfr.fr/Terezin/index.html

http://www.musicologie.org/publirem/petit_elise_musique_religion.html