Posts Tagged Holocaust

Three Cities – Vienna, Prague, Berlin

Posted by cathannabel in History, Personal, Second World War, The City, Visual Art on August 4, 2024

For most of my life, I’ve been fascinated by cities. My teenage years were spent in a rather ordinary dormitory village but I headed regularly for the nearest proper city (Nottingham) for shopping and football, and the annual Goose Fair. I’d previously lived in Kumasi (Ghana’s second city), and Zaria in the north of Nigeria. When I went off to University I settled in Sheffield where I still live, despite a few years commuting to Manchester, and a very brief period commuting to Leicester. My PhD thesis explored ideas about the city, about navigating and failing to navigate it, about the city as labyrinth, looking particularly at Manchester and Paris. And my idea of a really good holiday would be less likely to involve a beach (though a city that happened to have a beach would be quite appealing), but would definitely involve a lot of walking around in a city with heaps of history and culture.

A few years ago, I started to formulate an idea for such a holiday, encompassing two or three European cities, with as much as possible of the travel being by train. The idea never got very far when everything shut down, and we were barely starting to think again about travelling when M died, very suddenly, early one morning in October 2021. In the shock and grief that followed, I wasn’t really thinking about holidays in any practical way, but it did occur to me early on that they would be a challenge.

I can’t see myself travelling alone for any other than the simplest journeys. I take the train up to Dundee a couple of times a year to stay with friends, but always pick the direct trains, and I know I’ll be met at the station, and I went to Rome alone in December 2022, but was met at the airport, and had family to stay with. My biggest challenge in travelling alone is my highly deficient sense of direction. I got lost in Amsterdam on what should have been at most a ten-minute walk from my hotel to the conference venue – heck, I got lost in Leeds (with a similarly deficient friend) trying to get from the Trinity centre to the Grand Theatre. So the thought of a city break on my own is just too intimidating to contemplate – and of course the idea of getting lost in an unfamiliar city alone is something that triggers the hardwired caution that comes from growing up female. Add to this the fact that I am short and not particularly strong, and struggle with any case larger than a weekend holdall, so often have to rely on the kindness of strangers to get luggage on and off trains.

More than this, the pleasure of such a trip would be so diminished if I had no one to share it with. I’d need a travelling companion, and it would have to be a travelling companion who was (a) taller than me – not a major difficulty, most grown-ups are, (b) gifted with a good sense of direction, and (c) interested in the same sorts of things that I am, including with a high tolerance for WW2 history.

I said something about this dilemma one afternoon, sitting with my offspring, not long after M died. At which point the solution became obvious – my son A is (a) taller than me, (b) has an almost supernatural sense of direction and (c) is as much of a history geek as I am, with a similar interest in WW2. I started turning over in my mind what my ideal destinations would be, and Vienna, Prague and Berlin seemed to present the perfect mix of art, architecture and history, with a lot of WW2 and Holocaust sites to visit.

We started planning in earnest, once I’d checked with him that he wasn’t merely being kind when he agreed to go, but actually liked the idea, and worked out timings, and a wish list of places to go and things to see.

I decided, fairly early on in the planning, that whilst sites associated with the Jewish populations of those cities, and museums and memorials recording the destruction of those populations, were high on my list of places to visit, there would be no concentration camps. If I go back to Prague with more time, I will perhaps take a trip out to Terezín, but it was not a priority on this trip. A had visited Sachsenhausen on an earlier trip to Berlin (with school) but had no desire to go back again. This was the right decision – the history of those Jewish communities was less familiar to me than the history of the camps, and what I wanted was to honour the Jewish history of all three cities, and to see the people behind the statistics, in the Stolpersteine on the pavements, in the names on the battered suitcases from Theresienstadt, in the names painted on the walls of the synagogue.

This is a Holocaust heavy trip. I have been reading about and studying the Holocaust since I first encountered Anne Frank when I was probably around the same age as her, and I believe that if we do not understand it, or at least attempt to, we restrict and distort our understanding of post-war politics, history, art, literature and music, even of humanity. It was a significant thread in my PhD thesis, not just the Holocaust itself but how it can be written about, and I have often wrestled with the question of how – indeed, whether – fiction about the Holocaust can shed light. So, whilst I do totally understand why people would choose not to go to these sites, not to read those books or watch the documentaries, it is important to me to do so, to continue doing so. All that I have read, all that I know, has never desensitised me to its horror and it will never do so – the names and photographs, the individual stories, can and do still punch me in the gut. But I don’t go to these sites to get that gut punch, I go to continue to build my knowledge and understanding – and to pay my respects.

Part of my interest in visiting these three cities was to reflect on how they differ, and in particular how they approach their own WW2 history. Austria has described itself as Hitler’s first victim, but it is of course not quite that simple – there was enormous support for the Nazi party, and a long history of virulent antisemitism in Vienna, that ran alongside the major Jewish influence in culture and the arts as well as in business and politics. Czechoslovakia was, entirely straightforwardly, a victim of Nazi aggression, and Prague’s Holocaust memorial takes the form, most powerfully, of the names of the dead, painted on the walls of a synagogue. Berlin deals with its past – both the Nazi era and the injustices and brutalities of the DDR – with candour and without excuses, and its memorial is not about the Jews of Berlin or of Germany, but all of the murdered Jews of Europe.

This blog isn’t a guide to or a history of any of these cities. It’s an attempt to capture the experience, and my reflections on the experience, to help me remember it in all its richness. And I’ve included some of the research I did after we returned home, to find out, where possible, the stories behind the names on the Stolpersteine and other plaques, because for me this was a vital part of the trip. It is an entirely personal mix of anecdote, history, images and quotations and as such may not be a reliable source for anyone else’s city wandering…

Note: for clarity, I have used Terezín as the name of the Czech town, and Theresienstadt as the name of the Nazi ghetto/concentration camp which was created there. I have tried to be consistent with spellings, but Czech names are often to be found in multiple variants, so some inconsistencies may have slipped through.

VIENNA

We arrived on Monday evening, flew in from Manchester and got a train from the airport to the Hauptbahnhof, from where we just had to cross the road to get to our lovely hotel, Mooons (comfortable and welcoming – we were tired and a bit stressed after we’d checked in, having had a slightly less straightforward journey from the airport than we’d anticipated, and Sven the barman sorted out food and beers for us so we started to chill out and enjoy planning our time). We made the most of our two full days in the city – though there is plenty we didn’t see, buildings that we saw from the outside but didn’t go round, for example – I clocked up 59k steps, 40.5 kms. We managed to find some proper Viennese food – e.g. schnitzel and goulash, and good beer (I went for the darker beers, less lagery).

Tuesday:

From our very modern hotel, we were only a few minutes from the beautiful Belvedere Palace – we walked through the gardens which for me had strong Marienbad vibes (as in Alain Resnais’ French new wave masterpiece, Last Year in Marienbad, a film which has fascinated and haunted me for many years, and which I’ve previously blogged about on this site).

On to the Stadtpark, where we found a rather blingy statue of Strauss, and more tasteful ones of Bruckner and Schubert.

Clockwise: Mooons Hotel, Belvedere Palace, gardens and fountains, Last Year in Marienbad, Strauss statue in the Stadtpark.

Walking by the Danube – here there was graffiti, a lot of it political, e.g. re climate change. In general in Vienna, there was no litter, and an orderliness evident in what happened at pedestrian crossings, where no one walked until they were told to walk. It felt a lot safer than, say, crossing a road in Rome, where one feels as if the only way to ever get across is to walk and hope one isn’t immediately mowed down. (A told me of waiting in vain for the right moment at a crossing point in Rome, and another tourist facing the same dilemma saying cheerily, ‘OK, when in Rome…’ and launching himself into the traffic. The cars and bikes do weave around you but it never even starts to feel safe.)

There are two Jewish museums in Vienna. First up was the Museum Judenplatz, built around the excavated remains of the earliest synagogue in Vienna, destroyed in 1421 by order of Duke Albrecht V. It has a fascinating collection building up a picture of that early Jewish community, and of the exploration of the remains. The Jüdisches Museum nearby continues the story of Vienna’s Jewish population through the centuries. But there is a strange sense of a hiatus – not that the Holocaust is omitted but compared to Prague and Berlin, it is arguably underplayed, the job left to the bleak Whiteread memorial in the Judenplatz. This is a bunker, whose walls are made up of books with spines facing inwards to represent the victims whose names and stories are lost, 65,000 Austrian Jews. The names of the camps and other locations where they were murdered are inscribed around the memorial.

Stolpersteine (Schwedenplatz): Here there are three individual stones, and a plaque in memory of 15 unnamed Jewish women and men who lived here before they were deported and murdered (no details given) by the Nazis. The Stolpersteine commemorate Anna Klein, b. 14 Jan 1885, Josefine Steinhaus, b. 21 May 1884, Helene Steinhaus b. 3 August 1885. Deported to Maly Trostinec 27 May 42, killed 1 June 42. Maly Trostinec/Trostinets, a village near Minsk in Belarus, was not a location I was familiar with. Throughout 1942, Jews from Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia were taken there by train and then shot or gassed in mobile vans. According to Yad Vashem, 65,000 Jews were murdered in one of the nearby pine forests, mostly by shooting, but some estimates are much higher, up to 200,000.

Vienna State Opera (Staatsoper) We’d decided against trying to get tickets for any performance here because (a) cost, (b) I haven’t managed to entirely convert A to opera and (c) we didn’t want to commit an evening. That was the right choice – we walked for miles (see above), and in the evenings just wanted time to chill with some nice Austrian beers and talk over what we’d seen and make our plans for the following day. But the building itself is obviously magnificent. And we had seen inside anyway, in Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation…

Clockwise: Stolpersteine, graffiti by the Danube, Judenplatz, Whiteread Holocaust memorial, the Opera house and nearby street

St Stephen’s Cathedral (Stephansdom). As in Paris, the survival of this and other fine buildings was achieved by a refusal to carry out orders. The City Commandant had ordered the Cathedral to be reduced to rubble, but this was not carried out – unfortunately, as the Red Army entered the city, looters set fire to shops nearby, which spread and damaged the roof and destroyed the 15th century choir stalls. Much was saved, however, and reconstruction began immediately after the war, with a full reopening in April 1952.

Watching The Third Man makes one realise just how badly Vienna was damaged during the war – not devastated like Berlin, Hamburg, Dresden, but, as Elisabeth de Waal puts it, ‘desultory bombing by over-zealous Americans on the verge of victory, and the vindictive shelling by desperate Germans in the throes of defeat’ had resulted in ‘the gaps in the familiar streets, the heaps of rubble where some well-remembered building had stood’ (The Exiles Return, p. 57). One would not know it now. Clearly, given the fear that rebuilding would destroy the character of the city, the choice was made to rebuild it as it had been, as far as possible. Which gives Vienna that feeling of being preserved in aspic, a slight unreality.

We went a bit further afield, out to Schonbrunn Palace. We didn’t go round the palace itself, preferring to explore the gardens, and head up the hill to the Neptunbrunnen and the Gloriette, to enjoy the view, which was indeed glorious.

Clockwise: Schonbrunn Palace, Gloriette and Neptune fountain; Stephansdom

Maria am Gestade church – one of the oldest churches here, built 1394-1414

Memorial to liberating Soviet soldiers (Heldendenkmal der Roten Armee/Heroes’ Monument of the Red Army), in Schwarzenbergplatz, featuring a twelve-metre figure of a Soviet soldier. This was unveiled in 1945. It seemed to me remarkable that it was built so soon after the war ended, but then I hadn’t realised either that Vienna was liberated by the Red Army, or that in the hiatus before the other Allied Forces arrived, there was a real possibility of Stalin occupying all of Vienna. The memorial is about heroism in battle, not about the violence, particularly sexual violence, inflicted on civilians during and after the battle, and has been controversial and subject to vandalism over the years, including very recently in response to the invasion of the Ukraine.

Wednesday:

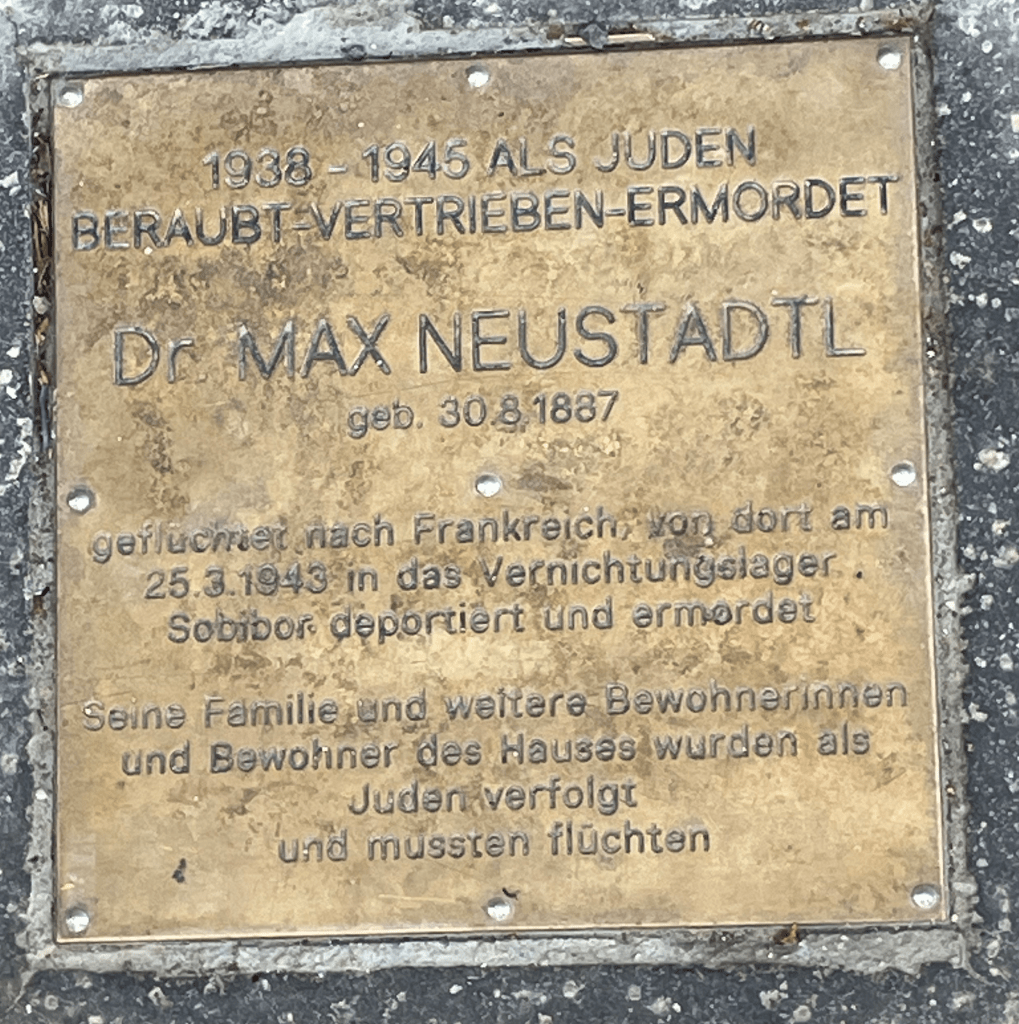

Stolpersteine: Paula Wilhelm (née. Mandl), born 6 April 1887, deported 29 April 44 to Auschwitz; and Dr Max Neustadtl who fled to France but was deported on 25.3.43 to the Sobibor extermination camp and murdered.

Vienna’s second Jewish Museum focuses on the later Jewish communities, covering the period of Nazi rule, but not dealing in great depth or detail with the Holocaust.

One fascinating display here is part of the collection of netsuke whose story is told in Edmund de Waal’s The Hare with the Amber Eyes. These are the Japanese miniature sculptures which belonged to the Ephrussi family, and which were kept out of the hands of the Nazis, unlike most of the contents of the Palais Ephrussi. Six weeks after the Anschluss, the family servant, Anna, was required to pack away the belongings of her former employers. There were lists, of course, to ensure that everything was accounted for. But each time that Anna was in the Baroness’s dressing room, she slipped a few of the netsuke into her apron pocket, and hid them in her room. In December 1945, Anna gave Elisabeth de Waal 264 Japanese netsuke.

‘Each one of these netsuke for Anna is a resistance to the sapping of memory. Each one carried out is a resistance against the news, a story recalled, a future held on to.’ (Edmund de Waal – The Hare with the Amber Eyes, pp. 277-83)

Clockwise: Stolperstein for Max Neustadtl, netsuke in the Jewish museum, Maria am Gestade church, stolperstein for Paula Wilhelm, Heroes Monument of the Red Army

A plaque on Herminengasse gives the names of Jews who lived here, in what was once part of the Jewish ghetto. Many Viennese Jews were forced to live here, until they were deported to various killing sites. Several were killed in Izbica (a town in Eastern Poland, which was turned into a ghetto) – all show the same date of death, 5 December 1942, when the inhabitants of the ghetto (Polish Jews, and those deported from Germany and Austria) were murdered. Those who escaped this massacre were deported again, to Treblinka, Maly Trostinec, Łódź Ghetto, Riga Ghetto, Theresienstadt, Sobibor, Stutthof. I know nothing about these people, other than their age, and where they were killed. But I can see that Oskar Koritschoner was only 20 years old when he committed suicide. Maly Trostinec was the place where 13-year-old Regine Frimet and 3-year-old Ernst Elias Sandor were murdered. And Josef Weitzmann, the last of these to die, was killed in Stutthof concentration camp, in 1944, just after the facilities for mass murder had been set up there. He was 18.

We found the Palais Ephrussi, on the Ringstrasse (see, again, The Hare with the Amber Eyes). I had had an insight into the efforts to trace the plundered contents of the Palais, from Veronika Rudorfer who I met in December 2019 at a conference, when she gave a talk on that project, and subsequently, very generously, sent me a copy of her beautiful book about the Palais itself.

The Burg Theatre – Sarah Gainham’s excellent novel Night Falls on the City has a lot of the action taking place at the Burg theatre, as her protagonist is one of its leading actors. One wouldn’t know that this building was largely destroyed in bombing raids during WW2, and then by a fire subsequently, and has been rebuilt.

Votivkirche (Votive Church) is a gorgeous, somehow delicate looking church, one of the most beautiful in a city of beautiful churches. It is in a neo-Gothic style and was built to thank God for the Emperor Franz Joseph’s survival of an assassination attempt in 1853.

Clockwise: Burg Theatre, Herminengasse plaque, Palais Ephrussi, Votivkirche

We saw the Rathaus – Vienna City Hall – and walked through the Burggarten where we found a statue of Mozart. Then the Resselpark (Karlsplatz), where we saw Sarah Ortmeyer and Karl Kolbitz’s 2023 memorial for homosexuals persecuted by the Nazis: ‘Arcus – Shadow of a Rainbow’, the colours of the rainbow changed to grey, combining grief and hope. There’s also a Brahms statue here, which I like very much.

On to Heldenplatz (Heroes Square), in front of the Hofburg Palace.

‘The two over lifesize equestrian statues on high pedestals are what give it its name, two great military commanders on rearing horses with flowing manes and tails in the Baroque style, one carrying Prince Eugene of Savoy and the other the Archduke Charles, brother of the first Emperor Francis who, in one victorious battle, had stemmed for a while Napoleon’s advance on Vienna. … And yet, with all their panache, there is so little boastfulness in this square. What first meets the eye and impresses the mind are the broad avenues of chestnut trees lining it on three sides … They give the square its peaceful, almost countrified look; they are conducive to slow perambulation and quiet contemplation.’ (Elisabeth de Waal – The Exiles Return, p. 227)

In sharp contrast to the above description, this is where Hitler made his announcement of the Anschluss after his triumphant arrival in the city.

Clockwise: Brahms statue in Resselpark, Heldenplatz, Mozart statue, Rathaus, Arcus memorial in Resselpark

Parliament Building – another building that was seriously damaged in WW2 and the restored to its former glory. In front of it is the Pallas Athene Fountain – apart from Athene (statuary in Vienna is often Graeco-Roman in subject matter and style) it represents the four major rivers, the Danube, Inn, Elbe and Vltava (Moldau in German).

Hofburg Imperial Palace – the official residence and workplace of the President.

Schwarzenberg Monument, commemorating Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg’s victory at the battle of Leipzig in 1813. Yet another equestrian statue (I cannot help it if the Bonzo Dog Doodah Band come to mind when I see these).

Here comes the Equestrian Statue

Prancing up and down the square

Little old ladies stop ‘n’ say

“Well, I declare!”Once a month on a Friday there’s a man

With a mop and bucket in his hand

To him it’s just another working day

So he whistles as he rubs and scrubs away(hooray)

(Bonzo Dog Doodah Band, ‘The Equestrian Statue’ (N. Innes), Gorilla, 1967)

Haus der Musik (Klangmuseum – museum of music and sound) is in the Palace of Archduke Charles, where the founder of the Vienna Phil lived around 150 years ago. The focus is on composers for whom Vienna was significant, with interesting material on Beethoven, Schubert, Mozart, Mahler, Schoenberg and others (not just biographical), as well as fun stuff about the science of music, my first encounter with a virtual reality headset (I didn’t do very well).

Clockwise: Haus der Musik, Archduke Charles monument, Hofburg palace (official residence and workplace of the President), Pallas Athene fountain, Parliament Building, Schwarzenberg monument

Kunsthistorisches Museum – in a palace (of course), purpose built by Emperor Franz Joseph 1 to house the rooms full of antiquities, sculpture and decorative arts. But the highlight was the picture galleries, and especially the Breughels, an absolute joy to see ‘Hunters in the Snow’ etc close up. Also paintings by van Eyck, Raphael, Durer, Holbein, Titian, Caravaggio…

What did we miss? Well, if I went back, I’d go to see the Klimts in the Belvedere gallery, I’d book a tour of the Opera House, and the Parliament building. Might even go on the Riesenrad (I think given the particular form my vertigo takes – see below – I would be OK with it, after all, I was fine on the London Eye).

Vienna Reading: Fiction: Sarah Gainham – Night Falls on the City/Private Worlds; Elisabeth de Waal – The Exiles Return. Non-fiction: Clive James – ‘Vienna’, in Cultural Amnesia; Edmund de Waal – The Hare with the Amber Eyes; Claudio Magris – Danube; Stefan Zweig – The World of Yesterday

Vienna on Film: The Third Man; Before Sunrise; Vienna Blood (TV detective series set in turn of the century (19th-20th) Vienna)

Vienna Music: Too much to mention – the city played such a key role in the lives and careers of so many great composers and musicians. Beethoven, Mozart, Schoenberg, Schubert, Brahms, Webern, Korngold… I did my best to avoid hearing ‘The Blue Danube’, a piece I heartily dislike, whilst in Vienna, but didn’t quite manage it (it’s a bit like trying to avoid hearing Wham at Christmas)

One lesser-known name, who I researched on our return. Marcel Tyberg was born and studied in Vienna but moved to Italy (present day Croatia) in 1927, when he was in his thirties. His mother followed the rules once the area was under Nazi occupation, and registered her Jewish great-grandfather. She died of natural causes, but Tyberg was arrested and deported, first to San Sabba camp in northern Italy, and then to Auschwitz, where he was murdered in December 1944. I listened to the Piano Trio in F major (1935-1936).

PRAGUE

Thursday:

We set off early to catch the train to Prague. Not the most scenic of journeys but travelling by train makes the journey part of the holiday and is generally less stressful. That is, once I was on board – the ‘mind the gap’ warnings do not adequately convey the hideous gulf between the train and the platform which involves one stepping out into said gulf and on to a narrow step before reaching the safety of the train. I realised this at Vienna Airport station but had vainly hoped that this wasn’t going to be the case with all the trains we caught… Fortunately A is both capable and caring, and so he grabbed the bags, put them into the train and then held my arms and made me look at him, not at the gulf, and step in. Same procedure in reverse when we got off the train, of course.

A slightly longer walk from the station to our hotel, the Majestic, near Wenceslas Square. A more old-fashioned looking hotel than Mooons but very comfortable. Having deposited our bags we set off for the Old Town. What I hadn’t anticipated is how much harder on the feet and the joints the cobbled streets in Prague would be – both of my days in the city had to be curtailed slightly early because on that first day there I crocked myself a bit. I still managed to clock up 17k steps (not bad for a half day), and 20k the following day, a total of 25.5km in the city.

Walking around Prague felt very different to walking around Vienna (and not just because of the cobbles). It is a city to wander in, to stroll down random streets, look around random corners, and be beguiled and intrigued by buildings that are a jumble of styles and eras, shapes and sizes. The terms ‘new’ and ‘old’ in Prague tend to mean ‘old’ and ‘really, really old’.

Clockwise: Charles Square, St Adalbert’s Church, Hotel Majestic, New Town Hall, view of the Zofín palace, a mysterious and ominous sign across the Vltava

Charles Bridge is always rammed with tourists – it is probably the most photographed site in the city, understandably enough. We got glimpses of it from the New Town side on Day 1, and the Prague Castle side on Day 2, when we did go part of the way across.

Jan Palach memorial, Wenceslas Square. I was 10, going on 11 at the time of the Prague Spring. I remember the news reports, and my parents’ distress (they vividly remembered the events in Hungary in 1956), and I remember hearing of Jan Palach’s suicide. A couple of years later, the English teacher at my school, an eccentric chap called Mr Pepper, mentioned this (I cannot recall in what context) and said that in a few years, no one would remember Jan Palach’s name. I decided that I would. And I did.

The Jewish Museum in Prague, based in the old Jewish quarter, comprises a number of locations – we didn’t see everything, but what we did see was unforgettable. It comprised four synagogues, the ceremonial hall, the old Jewish cemetery (and a gallery which was closed when we visited).

Pinkas synagogue – I knew what I was going to see. But that didn’t make it any easier. I wrote back in 2017 about a visit to the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris: ‘I had braced myself for this, knowing the terrible history that would be illustrated there. Nonetheless, seeing the Wall of Names, I felt the air being sucked from my lungs, realising that I was seeing in that moment only a fragment, only some of the names from only one of the years’. That’s how I felt in the Pinkas synagogue, where the Memorial to the Victims of the Shoah from the Czech Lands comprises their names on wall after wall after wall. The names are painted on, which gives them a certain fragility, that they could fade away, unlike the stones in the Paris memorial. They mustn’t, obviously. They need to be there for generation after generation, to see wall after wall of names, each a person with a story, with a life, with a potential future.

‘The storm is within, a blizzard that stings the eyes and batters on the mind. Not snow or sleet but names. Names everywhere, names on the walls, names on the arches and the alcoves, ranks of names like figures drawn up on some featureless Appellplatz. Names and dates: given names and dates in black, surnames in blood. Dates of birth and dates of death. Seventy-seven thousand seven hundred and ninety-seven of them, names so crowded that they appear to merge one into the other and become just one name, which is the name of an entire people – all the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia who died in the camps.’ (Simon Mawer – Prague Spring, pp. 218-19)

From the Pinkas synagogue to the old Jewish cemetery, in use from the first half of the 15th century till 1786 – the oldest gravestone is from 1439. It’s the ‘Prague Cemetery’ which gives Umberto Eco’s novel its name (a book that is now on my To Read list). (We didn’t visit the New Jewish cemetery to pay our respects to Kafka – maybe next time, especially if I manage to read a few more of his works before then). We saw the Jewish ceremonial hall, and the Klausen synagogue but didn’t go in. But we couldn’t miss the ornate gorgeousness of the Spanish synagogue, whose decoration imitates the Alhambra.

Clockwise: Pinkas Synagogue, Jan Palach memorial, Jewish ceremonial hall, Old Jewish cemetery, Spanish synagogue

The Old Town Hall is actually a medley of a number of buildings of various sizes and ages, stitched together (if I may mix my metaphors) over the centuries. At various times, bits of it were demolished/rebuilt/amended in various ways. In 1945 during the uprising in the city, a couple of wings were destroyed by fire. On another visit, I would be very intrigued to look around this properly.

The Town Hall’s most famous feature is the rather marvellous 15th century Astronomical Clock. We missed its most marvellous moment though as we failed to be there at the right time to see the apostles emerge.

Stolpersteine (Nové Město): four members of the Gotz family. Rudolf was 49, and his wife Marie 48 when they were deported from Prague to Theresienstadt; two years later both were transported to Auschwitz where they were murdered. Their sons Raoul and Harry made the same journeys at slightly different times than their parents. They were 21 and 16 respectively when they were deported, four months before their parents, to Theresienstadt, and then in September 1943, a year before their parents, to Auschwitz.

Clockwise: Astronomical Clock, Church of St Nicholas, stolpersteine for the Gotz family, Kranner’s Fountain (monument to Emperor Francis 1 of Austria), the Old Town Hall, Old Town Square

At this point, I consented to return to the hotel and put my feet up, whilst A headed off to the Prague Museum.

Friday:

Day 2 – with my feet properly blister-plastered, and a comfier pair of shoes, we headed (via the tram) to the Prague Castle complex. There’s a lot to see here, and the views of the city are stunning.

We walked through the Royal Gardens, with beautiful buildings around them, including Queen Anne’s Summer Palace. We saw a red squirrel here – I’m honestly not sure that I’ve seen one before, but we then saw another in Berlin.

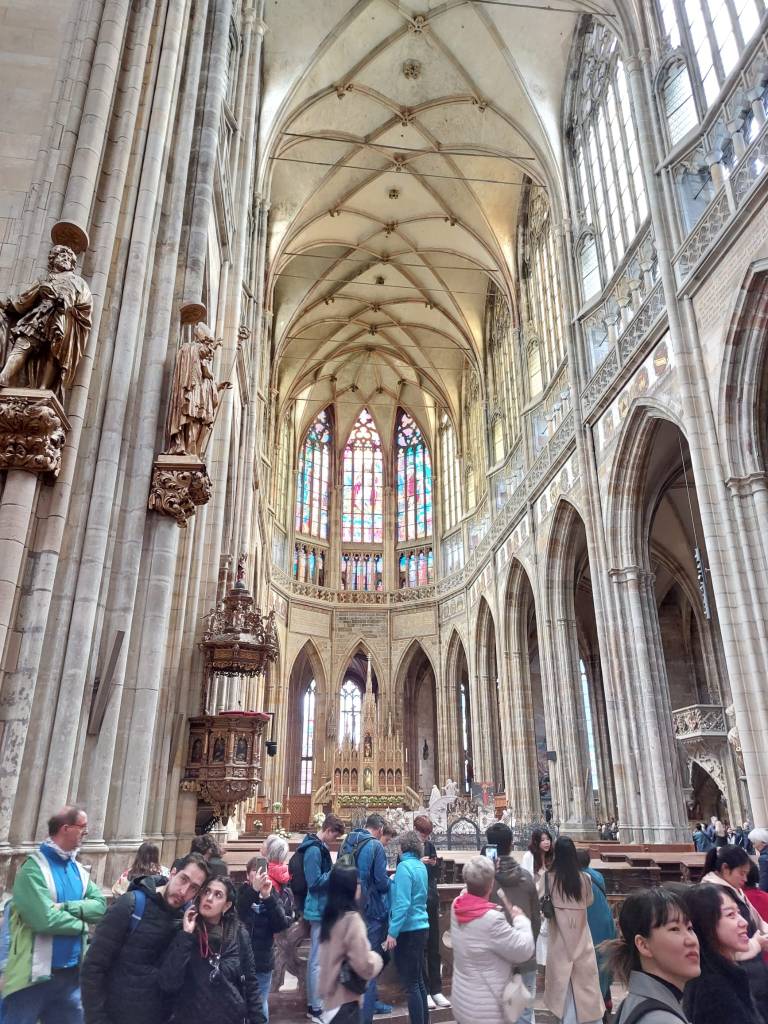

St Vitus Cathedral – this took nearly 600 years to complete, 1344-1929. One of the final stages involved the installation of the beautiful stained glass. Czech art nouveau painter Alfons Mucha decorated the windows in the north part of the nave, František Kysela the rose window. Even though half of the cathedral is a neo-Gothic addition, much of the 15th century design was incorporated in the restoration.

Going up the Great South Tower was an optional extra which I unhesitatingly declined. I have been frozen with fear on spiral staircases in many of the ancient buildings of Britain, and in the Arc de Triomphe (with a posse of French schoolkids behind me helpfully going ‘Allez! Allez!’). So I let A go up the tower – there were a lot of steps, and it was indeed a spiral, but worth it (he tells me) for the view from the top.

The Basilica of St George is the oldest church building on the castle site, dating from 920.

Clockwise: Basilica, Cathedral interior, Cathedral, Great South Tower, Royal Gardens, stained glass in the Cathedral, Chapel of the Holy Cross, Castle interior, Queen Anne’s Summer Palace

Golden Lane is a pretty alleyway of tiny, brightly coloured cottages. These were built for the members of Rudolf II’s castle guard and takes its name from the goldsmiths who later occupied the cottages. Kafka came here in the evenings to write, during the winter of 1916.

12 Šporkova is the building where W G Sebald’s Austerlitz found the apartment that his parents had occupied. The fictional Jacques Austerlitz left Prague in 1938 to come to the UK as part of the Kindertransport. He was brought up without knowing anything of his origins but becomes haunted by the absence of his past and starts to search for information about his parents.

‘The register of inhabitants for 1938 said that Agáta Austerlitz had been living at Number 12 in that year… As I walked through the labyrinth of alleyways, thoroughfares and courtyards between the Vlašská and Nerudova, and still more so when I felt the uneven paving of the Šporkova underfoot as step by step I climbed up hill, it was as if I had already been this way before and memories were revealing themselves to me not by means of any mental effort but through my senses, so long numbed and now coming back to life.’ (W G Sebald, Austerlitz, pp. 212-13)

Austerlitz finds his old neighbour, and learns that his mother was deported to Theresienstadt, and from there to Auschwitz. His father had already left for France before his own escape, and by the end of the book Austerlitz is still searching for information about whether he survived (or how he died).

We didn’t knock to try to go in and see if the hallway and stairs are as Sebald described – in any event, I don’t know whether Sebald himself ever did so. There are a couple of photographs embedded in the text but as always with Sebald, we can’t assume that their positioning tells us what they are. Sebald visited Prague in April 1991, and again in April 1999, at a time when he would have been writing Austerlitz, and it seems likely that he at least did as we did and wandered down Šporkova and looked at the doorway. But did he choose this location arbitrarily, or did he have some information about its past that encouraged him to link it to his fictional protagonist? As always, Sebald mingles fact and fiction in a most fascinating, infuriating, and sometimes highly problematic way (see my PhD thesis for (much, much) more on this topic!).

Estates Theatre – another Sebald connection: Austerlitz’s mother was an actress who performed at the Estates Theatre. It dates from the 1780s, and saw the premieres of Don Giovanni and La Clemenza di Tito, as well as the first performance of the Czech national anthem. It can also be seen in the film of Amadeus during the concert scenes, standing in for Vienna, as it is one of the few opera houses in Europe still intact from Mozart’s time.

I didn’t see the extraordinary Dancing House myself – on day 2 in Prague I again had to bail early (those bloody cobbles), and so A went on alone, to see this building which had intrigued him from the guidebook. The Dancing House, or Ginger and Fred, was designed by architects Vlado Milunić and Frank Gehry on a vacant riverfront plot in 1992 and completed in 1996.

Clockwise: 12 Šporkova, the Dancing House, Estates Theatre, Golden Lane, Prague Museum, Morzin and Thun palaces.

A also visited the Ss Cyril & Methodius Cathedral, site of the last stand of seven members of a Czech resistance group including Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš, who had assassinated Heydrich. They were betrayed, and the church was surrounded by 750 SS soldiers, water pumped into the crypt to try to force them out, until all were killed or had committed suicide. We were both familiar with their story from the film Anthropoid – I’d also read Laurent Binet’s HHhH, and seen the film adaptation of that, The Man with the Iron Heart.

Wenceslas Square, near our hotel. The site of celebrations and demonstrations, and home of the statue of St Wenceslas (this isn’t the original one – that was moved elsewhere in 1879, this one dates from 1912). The National Museum, which A visited on Day 1, is at the top of the square.

Clockwise: Charles Bridge, the crypt of Ss Cyril & Methodius Cathedral, Memorial to the Czech resistance, Ss Cyril & Methodius, Wenceslas Square, Prague viewed from the Castle

What did we miss? We only saw the modern part of Prague station, not the older building, nor the Kindertransport memorials there. We didn’t get to Petrin, and the funicular railway, the observatory, mirror maze or the mini Eiffel Tower (Rozhledna). But if we come back, we’d probably just spend more time wandering, I think, because there’s something to see around every corner here, not necessarily something grand like in Vienna, but something intriguing, something beautiful, something memorable.

Prague Reading:

Fiction: Lauren Binet – HHhH (a fictionalised account of the assassination of Heydrich); Franz Kakfa – The Castle (it’s not really about Prague Castle but still…); Simon Mawer – Prague Spring; W G Sebald – Austerlitz; Philip Kerr – Prague Fatale; Heda Margolius Kovaly – Innocence (a Prague-set detective noir). Non-Fiction: Anna Hajkova – The Last Ghetto: An Everyday History of Theresienstadt; Heda Margolius Kovaly – Under a Cruel Star (also published as Prague Farewell), her autobiography, covering imprisonment in the Łódź ghetto and Auschwitz, her return to Prague and the judicial murder of her husband during the Slansky show trials, finally leaving after the failure of the Prague Spring; Alfred Thomas – Prague Palimpsest: Writing, Memory and the City (especially Ch. 5 which deals with Sebald’s Austerlitz).

Prague on Film: Anthropoid; The Man with the Iron Heart; Kafka (TV series)

Prague Music: Smetana – ‘Ma Vlast’ is the obvious piece, and a wonderful one, whether one is looking out over the Vltava whilst listening or not and Janacek and Dvorak are composers who have been part of my musical life for so many decades. It’s also important to recognise the work of a number of composers who were deported to Theresienstadt, and who composed and performed music in the ghetto, before being transported to Auschwitz and murdered, notably Gideon Klein, Hans Krása, Viktor Ullmann and Pavel Haas. Inevitably much of the music is lost but what has been recovered can be found on various collections and compilations, as well as on Spotify. I also rather like Martina Trchová, a Prague-born folky singer-songwriter.

BERLIN

Onwards to Berlin. Another train, this one with old-fashioned compartments. A more scenic route than the one between Vienna and Prague (and I’m definitely not talking about the man who emerged from a shrubbery alongside the rail track, naked apart from a beanie hat).

Our hotel was immediately opposite the Hauptbahnhof, but we weren’t able to check in straight away, so we deposited our bags and headed out into the city.

Saturday:

We headed out, noting some striking pieces of political art in Kreuzberg, and the EU project, Path of Visionaries, in Friedrichstrasse, where a floor plaque bearing a quote from someone inspiring is in place for each EU member state, plus UNESCO. I didn’t check whether we had a floor plaque, but when the project was launched in 2006, we were still in the EU…

Berlin’s Jewish Museum is a powerful place to visit, both in terms of its design and its content. We particularly noted the Garden of Exile and Emigration, described here by blogger Gerry Condon:

’49 columns filled with earth are arranged in rows traversed by uneven pathways. The stelae are built on sloping land and rise at an angle, leading to a sense of disorientation similar to that felt inside the museum building. Out of each column grows an Oleaster, an Olive Willow, perhaps symbolizing rebirth. The experience of walking in this structure is comparable to that of being in the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, but though the Garden of Exile and Emigration is more modest, I think I found it more effective.’ (Gerry Condon, ‘Living with History: A Berlin City Centre Walk’, How the Light Gets In, 25/06/15)

We hadn’t at this point seen the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, but certainly the Garden was disorienting; I stumbled as soon as I went in and felt off balance whilst I was in there. But there was beauty too, sunlight, and growth.

The corridors in the Museum itself are intersecting and slanting ‘Axes’, and there are a number of voids. We looked down into the Memory Void but didn’t find our way to go into it (it’s the only one of the voids that one can enter), bamboozled by the labyrinth. But from our vantage point we could just see the ‘Fallen Leaves’ (designed by Israeli artist Menashe Kadishman), each with a face punched out of steel and covering the floor of the void so that visitors have to walk over them.

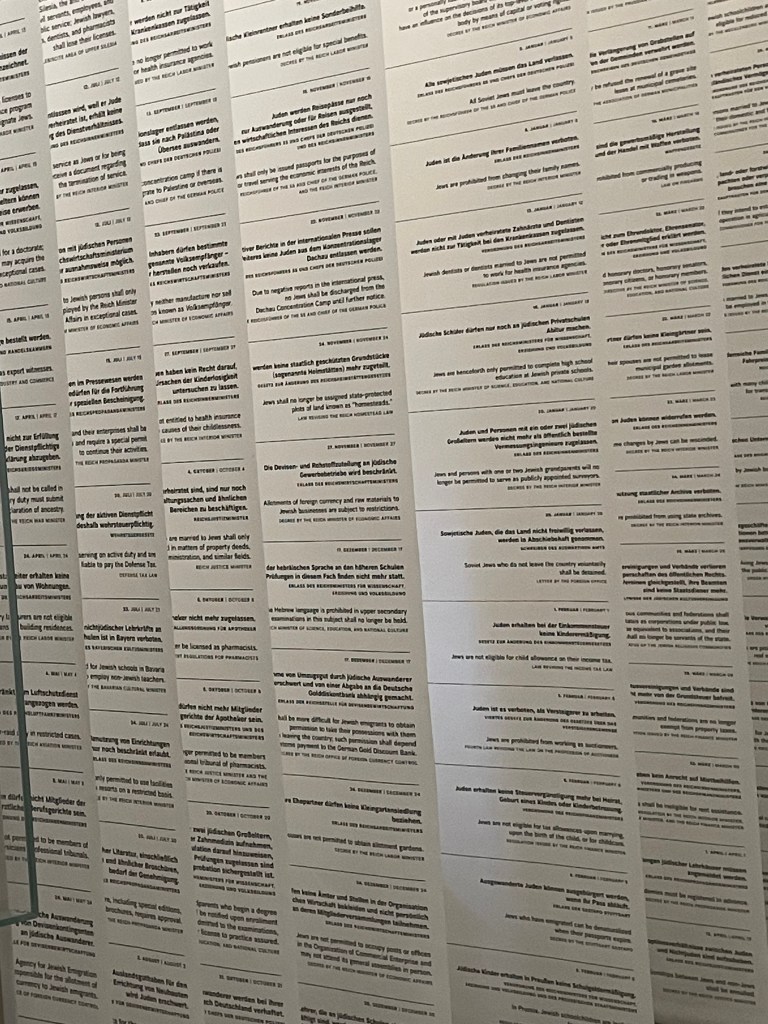

The permanent exhibition is of Jewish past and present in Germany, but there are displays that recognise the diaspora, and the continuity of Jewish life and traditions in the many nations where exiles found a home. We were very struck by the display showing, in a series of long hanging posters, covered in small print, the many, many laws implemented by the Nazi party as soon as they had power, laws covering every conceivable aspect of life for Jews. It didn’t, as we know, start with gas chambers, or even with deportations. It started with minutiae, with things that people initially may have felt they could cope with, and little by little these restrictions isolated the Jewish population from Aryan neighbours, colleagues, classmates, so that they were exposed, without allies (or only those brave enough to take a stand), when everything was finally taken from them.

We also saw an exhibit about Regina Jonas, the first woman Rabbi, born in Berlin and ordained in 1935, an inauspicious year. I hoped initially that she had perhaps been able to leave before it was too late, but a moment’s googling told me what I kind of knew in my bones, that she stayed. She was arrested in 1942 and deported to Theresienstadt, where she continued to work as a rabbi, helped with a crisis intervention service to support newcomers to the camp, and was involved in cultural and educational activities. In October 1944 she was deported to Auschwitz, where she was murdered either on arrival or two months later, aged 42.

Clockwise: Garden of Exile and Emigration (Jewish Museum), Hotel Amano, Nuremberg laws (Jewish Museum), Path of Visionaries, Regina Jonas, street art

Stolpersteine (Luisenstadt): Hirsch Neumann died 30 Oct 1940, Max Neumann, Rosa Reha Neumann, killed Riga Jan 42; Nathan Moritz Carlé, Charlotte Carlé, Margarete Carlé, Alice Carlé, Theresienstadt, Auschwitz. I was unable to find more information about Hirsch, Max and Rosa Neumann, but the story of the Carlé family is worth recounting:

Nathan and Margarete Carlé lived in Frankfurt when they first married, and their first child, Hans, was born there. They then moved to Berlin in 1900, where their daughters Charlotte and Alice were born. They moved around a fair bit in Berlin as their economic circumstances waxed and waned. In 1942, Margarete and Nathan were deported to Theresienstadt, where Nathan died on 11 October (reportedly of a heart defect). Margarete died of a stroke four months later. Whilst Theresienstadt was neither a death camp nor a work camp, conditions – massive overcrowding, malnourishment, and the spread of disease – killed many of its inhabitants, especially those who were older or otherwise vulnerable, before they could be deported to Auschwitz. Alice, their younger daughter lived with her partner Eva Siewert, until Eva was denounced in 1942 for having made anti-fascist jokes and sentenced to nine months in prison. Alice and her sister Charlotte lodged with Elsbeth Raatz, until threats of denunciation forced them to leave – Raatz, however, gave them false passports. In August 1943, they were arrested by the Gestapo and deported to Auschwitz a few weeks later. Of the 54 people in this transport, only nine women were registered as new arrivals (i.e. selected for work rather than immediate death). We don’t know their names, so we don’t know whether Alice and/or Charlotte were amongst those or had been murdered on arrival in the camp. Alice’s lover Eva survived, and worked as a journalist in Berlin after 1945. Hans Carlé had left Germany in autumn 1933, initially for the Netherlands, and then emigrated to Palestine, where he married. He lived a fairly precarious life in Tel Aviv, and died of a heart condition in 1950, aged 51.

Fernsehturm – we did not go up on this visit (A had already done so on his previous trip to Berlin), but we saw it – obviously, since it is the ultimate photobomber, popping up in almost every photo taken in the centre of Berlin.

We saw but did not go into the Berlin Palace, on Spree Island. A building that would have barely been noticeable in Vienna, where palaces are around every corner, it’s very striking here. But it’s actually a reconstruction. It was damaged by Allied bombers but actually demolished by the DDR government in 1950. In its place was the modernist Palace of the Republic, the DDR Parliament building. After reunification, and after long and arduous debate, the DDR building itself was demolished and most of the Berlin Palace’s exterior was reconstructed. It now houses the Humboldt Forum museum.

Berlin Cathedral, built in the late 19th century, damaged by Allied bombing and subsequently restored.

Clockwise: Berlin Cathedral, Berlin Palace, Stolpersteine: Carlé family, Fernsehturm, Humboldt Hafen (the canal harbour), Stolpersteine: Neumann family

Rotes Rathaus, Berlin’s town hall. It was the town hall for East Berlin, and the name ‘red town hall’ indicated not only the colour of the stones, but also the political colour. Mid-19th century, heavily damaged by Allied bombing, and rebuilt.

When we finally got into our room that evening (we’d decided to share, for economy), we were somewhat discomfited to discover that whilst there was, thankfully, a proper door on the toilet, the shower cubicle was all glass, and with a clear view through from the bedroom area, enhanced by the enormous mirror on the wall opposite the shower, just to make sure that the showerer would be visible from almost all points in the room, in all their glory. We devised a plan whereby the showerer would give a warning that clothes were about to be shed and the non-showerer would settle at the furthest top corner of the bed, facing the wall, and focusing intently on their phone or Kindle until the all-clear was sounded. We have since learned that this sort of thing is dismayingly common in modern hotels, in parts of Europe at least, and we don’t think much to it…

Sunday:

We headed for the Tiergarten but hadn’t fully realised the impact of the Berlin Half Marathon, which was taking place that morning. Our original route was quite impossible, so we only got a brief stroll through the Tiergarten before having to exit.

Reichstag – we’d tried to book a tour, but had evidently left it too late, or tours were unavailable due to the half marathon. Another time.

Marie Elisabeth Lüders House (Scientific dept of German govt) – On the banks of the Spree are memorials to people killed trying to cross to the West. This new building, inaugurated in 2003, owes its name to social politician and women’s rights campaigner Marie Elisabeth Lüders. Parts of the Berlin Wall have been rebuilt here to commemorate the division of the city along the former route of the Wall.

We failed to do justice to Museum Island but did go round the Alte Nationalgalerie. The problem with galleries is that once one has been through a number of rooms of paintings, it’s hard to remember exactly what one has seen, and to keep in mind the things that one particularly enjoyed and I really wish I’d made some notes. As far as I can recall, we rather liked the Romantics and the Impressionists, and I think Arnold Bocklin and Caspar David Friedrich stood out.

Solidarność wall – a section of brick wall from the shipyard at Gdansk commemorating the struggle for democracy in Poland through the Solidarity movement. I cannot find any information online about this, oddly. It’s adjacent to the Reichstag building.

Clockwise: Altenationale Gallery, Altes Museum, Reichstag, Rotes Rathaus, Solidarity wall, memorial to those killed attempting to cross from East Berlin (Marie Elisabeth Lüders House)

The Brandenburger Tor was the finishing line for the Half Marathon, and our arrival coincided with the first runners crossing the line, so we stayed and cheered for a while. Of course it is one of those sites that is iconic (a much over-used word, but here I mean that as an image it stands for Berlin in the same way that the Eiffel Tower stands for Paris), and I’ve seen it a lot recently, in coverage of the Euros. What seems remarkable is that it survived the final stages of the war, damaged but still standing, whilst so much of Berlin was reduced to rubble. Also remarkable is that shortly after the war, East and West Berlin cooperated in repairing some of the damage. Thereafter it was obstructed by the Wall and became a symbol of the city’s division – and then of its reunification after the Wall came down.

We had lunch with my friend Veronika, which was a brilliant opportunity to talk about all three of the cities we’d visited – she’d grown up and then worked in Vienna, now works in Berlin, and had visited Prague often, so it was fascinating to get her perspective on our experiences and to catch up on what had been happening since we met in December 2019.

After lunch, on to the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe:

‘Two thousand seven hundred eleven concrete rectangles, as if a field of chiselled coffins of varying heights stand in formation, separated by just enough space for people to walk between them and contemplate their meaning. The stones undulate and dip towards the centre, where the ground hollows out, so that when a visitor reaches the interior, the traffic noise dies away, the air grows still, and you are trapped in shadow, isolated with the magnitude of what the stones represent. This is the memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe who perished during the Holocaust. There is no sign, no gate, no fence, no list of the 6 million. The stones are as regimented as the Nazis and as anonymous as the captives shorn of identity in the concentration camps.’ (Isabel Wilkerson – Caste, pp. 343-4)

Opinions, as one might expect, differ about this memorial, about its purpose and the form it takes. I was surprised how similar that form was to the Garden in the Jewish Museum, although it is bleaker, somehow. But whatever form the memorialisation of the Holocaust takes, some will find it does not speak to them, or will question its location or how it presents itself (of course some will question the need for such memorials, but that question seems to me obscene in its ignorance). I did find it effective and oppressive, and the scale is very striking (the Garden does not attempt to convey that), and I applaud the use of the term ‘murdered’ here. When we speak of people dying in the Holocaust, or being killed, we diminish what was done. One might die of anything; one might be killed in a car crash. Whether through bullets or gas, disease or starvation, these deaths were planned and intentional, they were murder on an unimaginable scale.

Topography of Terror Museum, on the site of the Gestapo/SS headquarters, and one of the longest extant sections of the Wall. We didn’t exhaust this because we (or at least I) were, frankly exhausted. But we saw the open-air part of the museum, and the remains of some of the walls of the buildings once occupied by the Gestapo. It was an excellent display – much that I did not know or had not understood in context.

‘Had to get the train

From Potsdamer Platz

You never knew that

That I could do that

Just walking the dead’ (David Bowie – ‘Where Are we Now’, The Next Day, 2013)

Clockwise: Brandenburg Gate, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Potsdamer Platz, Tiergarten, Topography of Terror

What did we miss? More here than elsewhere, partly because there’s more to see, but also because our planned route for Sunday was disrupted by the Half Marathon, and to be honest, because we were knackered. If/when I go back, there are several museums to see, and I’d particularly like to focus more on the post-war DDR history – the Wall, the Stasi, etc – as well as doing the Reichstag tour, and going up the Fernsehturm for the sake of the view.

Berlin Reading:

Fiction: Christopher Isherwood – Goodbye to Berlin; Philip Kerr – Berlin Noir trilogy; John le Carré – The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. Non-fiction: Walter Benjamin – Berlin Chronicle; Sinclair McKay – Berlin: Life and Loss in the City that Shaped the Century

Berlin on Film: Wings of Desire; The Resistance; The Lives of Others; Cabaret

Berlin Music: Obviously, there is plenty of ‘classical’ music from composers who were born in or who studied in Berlin. But the soundtrack in my head was made up of the voices of Marlene Dietrich, Lotte Lenya, and David Bowie.

Final thoughts

Seeing three cities in six days invites one to make direct comparisons.

Vienna was grand, and beautiful, seemingly fixed in the nineteenth century, before all of that mid-twentieth-century unpleasantness. My response to the city was coloured by a conversation with a neighbour whose father, it turned out, had grown up there, but had had to leave, along with his family – of those who remained, many were murdered. She felt it was a soulless place, cold and hostile to her which, in a fundamental way it was – had her father not escaped it, she would probably not have existed. Another friend, who grew up in Vienna much more recently, spoke of it as claustrophobic, particularly for a teenager. So we admired its beauty but did not fall in love.

Prague is older, more of a muddle of labyrinthine streets and architectural styles, but just as beautiful in its own, less grand, way. And in the Jewish quarter of the city it acknowledges both the long history of that community, and how that was destroyed, in a simple and moving way, through the names and what that list of names conveys, rather than anything monumental. Prague took our hearts.

Berlin has, of course, a lot more to acknowledge, and it does so in various powerful ways. It leaves gaps, it leaves fragments.

‘Berlin is a naked city. It openly displays its wounds and scars. It wants you to see. The stone and the bricks along countless streets are pitted and pocked and scorched; bullet memories. These disfigurements are echoes of a vast, bloody trauma of which, for many years, Berliners were reluctant to speak openly. … The city itself is long healed, but those injuries are still stark.’ (Sinclair McKay, Berlin, p. xvii)

Its history is so complex and reflects not just one nation but two in the one city, as well as reflecting upon not just Germany (one or both) but what was done to so many in the name of that nation. There are layers upon layers to explore – and we inevitably did scant justice to that.

But we knew that seeing three cities in six days – three cities chosen because of their complex and fascinating history, their beauty and tragedy – was going to leave us with almost as long a list of things that we missed as our original list of things we wanted to see. Some of those omissions were choices – we favoured wandering around the streets over excursions that would take too big a chunk of our time, and I’m glad we did. I missed some things because I reached the end of my capacity for walking rather sooner than A did, and decided to conserve energy for the following day by a strategic withdrawal to the hotel room a little earlier than we’d intended. And there are things that we hadn’t even added to our list, that we’d include next time.

But we saw a heck of a lot, we walked for 57 miles, and I clocked up 135k steps, and we saw museums and art galleries, cathedrals, churches and synagogues, a cemetery, palaces, memorials, statues and fountains, parks and government buildings, paintings and stained glass windows, stolpersteine and commemorative plaques, three great rivers (the Danube, Vltava and Spree), street art, theatres and opera houses, bridges… We sampled the local culinary specialities (schnitzel, apfelstrudel, goulash, pork knuckle, various forms of sausage) and the local beers.

It was a trip that I dreamed up and I was afraid it wouldn’t live up to that dream, but it did, it was everything that I had hoped it would be. When we got home, it almost seemed dream-like – had we really seen and done all of that? Hence this epic blog – I needed to capture it all before memories got too hazy. I could not have done it without A and his company was not only practically essential, but also a joy. I am hugely grateful to him for making that dream a reality.

Marks of Pain: Architecture as Witness to Trauma in W G Sebald’s Austerlitz

Posted by cathannabel in Genocide, History, Second World War, W G Sebald on September 10, 2019

This is an edited version of a talk given at the 2019 Conference, Violent Spaces, of the Landscape, Space & Place group from the University of Nottingham.

Few late twentieth-century writers are held in such regard as W G Sebald. His work has inspired not only glowing reviews and a host of journal articles, edited volumes and monographs – but also responses by visual artists and filmmakers. There are certain themes that are most often associated with his work – time, loss, trauma, memory… These themes inevitably link to one particular aspect of his work – his writing about the Holocaust.

W G Sebald was born in Bavaria in 1944, in the last months of the war. His father had served in the Wehrmacht, but after he returned home, having spent a couple of years as a prisoner of war, the things that he had seen, and done, were never spoken of. And when Sebald as a teenager was shown documentary footage of the camps (probably the liberation of Belsen) no context or commentary was provided. It was, in a way, what we’d now call a box-ticking exercise. Because, of course, the teachers were part of the context. Sebald, like many of his contemporaries, was unable to accept this collusive silence, and his increasing alienation from his homeland led to him working first in Switzerland and then moving to the UK, where he spent the rest of his life, teaching at UEA until his death in a car accident in 2001.

The Holocaust, indeed, became a presence in his poetry and his prose writing. It seems never to be very far away, invoked maybe by the name of a place, innocent in itself, but carrying the weight of history. In many of his works, it is addressed obliquely, but the figure of the refugee appears in several of his books. Max Ferber, one of the four protagonists of The Emigrants, left his home in Munich (capital of Bavaria) in 1939, following Kristallnacht, his father having obtained a visa for him by bribing the English consul. We are introduced to Ferber via the narrator, who does not ask about his history, why or how he left Germany, until their second meeting, at which point Ferber tells how letters from his parents ceased, and he subsequently discovers that they were deported from Munich to Riga, where they were murdered. In Sebald’s final work, Austerlitz, the Holocaust becomes text, not subtext, foreground rather than context.

Sebald’s (fictional) protagonist, Jacques Austerlitz, is an architectural historian, with a particular interest in what he calls ‘our mightiest projects’ – fortifications, railway architecture, what they used to call lunatic asylums, prisons and law courts.

He’s also fascinated by the idea of networks, such as ‘the entire railway system’. From the outset, whilst Austerlitz himself does not make any connection between these edifices and the event that shaped his life, we are given foreshadowing of that event. He says of railway stations, for example, that he can never quite shake off thoughts of the agonies of leave-taking – and we’ll see the significance of that later. He refers to ‘the marks of pain which, as he said he well knew, trace countless fine lines through history’.

We meet the narrator first in a carceral space – Antwerp’s zoo. After his first conversation with Austerlitz, he is moved to visit Breendonk, one of the fortresses that Austerlitz had mentioned.

But it is not the history of how such places were designed, the flawed theories of defence against enemy incursion, that confront him there, but the much more recent past, Breendonk’s conversion into a concentration camp in the Nazi era – a transit camp for deportation to Auschwitz, and a place of torture.

- Originally built for the Belgian army 1906-13 to protect Antwerp – ‘it proved completely useless for the defence of the city and the country’

- Covered by a five-metre thick layer of soil for defense against bombings, a water-filled moat and measured 656 by 984 feet (200 by 300 m)

- Requisitioned by the Germans as a prison camp for political dissidents, captured resistance members and Jews

- Infamous for prisoners’ poor living conditions and for the use of torture. Most prisoners later transferred to larger concentration camps in Eastern Europe

- 3,590 prisoners known to have been imprisoned at Breendonk, 303 died or were executed within the fort itself and as many as 1,741 died subsequently in other camps before the end of the war

Sebald brings in a human witness here, Austrian writer Jean Amery, who was interned and tortured at Breendonk before deportation to Auschwitz and later Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen. He survived, changed his name from the obviously Germanic Hans Meyer, but committed suicide in 1978.

Our narrator finds Breendonk to be a place of horror. The darkness inside is literal, but also metaphysical, and it becomes heavier as he penetrates further into the building. He begins to experience visual disturbances – black striations quivering before his eyes – and nausea, but explains that ‘it was not that I guessed at the kind of third-degree interrogations which were being conducted here around the time I was born’, since he had not at that point read Amery’s account. Sebald is telling us that the narrator’s reaction to Breendonk is not, therefore, personal, not related in any way to his own experiences or even to things he had read, but intrinsic to the place, as if its use, or abuse, has changed its very nature, violence become part of its fabric.

Breendonk is the first of the trio of Holocaust sites around which the text is structured. It’s built to a star shape, a six-pointed star. This was a favoured design both for fortresses, designed to keep invaders out, and for prisons, designed to keep wrongdoers in.

According to Austerlitz this is a fundamentally wrong-headed design for a fortress, the idea that ‘you could make a city as secure as anything in the world can ever be.’ The largest fortifications will attract the enemy’s greatest numbers, and draw attention to their weakest points – not only that, but battles are not decided by armies impregnably entrenched in their fortresses, but by forces on the move. Despite plenty of evidence (such as the disastrous Siege of Antwerp in 1832), the responses tended to be to build the same structures but stronger and bigger, and with inevitably similar results.

As the design for a prison, the star shape makes more sense. It does not conform to the original layout of the panopticon, but it does allow for one central point of oversight and monitoring, with radial arms that separate the inmates into manageable groups. The widespread use of existing fortresses as places of imprisonment for enemies of the Reich was primarily opportunistic, of course, but the ease of this transformation illustrates Austerlitz’s arguments quite well.

Sebald had previously been struck by his encounter with Manchester’s Strangeways prison, which has the same shape, ‘an overwhelming panoptic structure whose walls are as high as Jericho’s’, and which happens to be situated in the one-time Jewish quarter. The coincidence of the hexagram star is implicit in the above. But it becomes entirely explicit when we look at the second of Sebald’s sites, Terezin.

- Some 70 km north of Prague

- Citadel, or small fortress, and a walled town, known as the main fortress – never tested under siege

- The small fortress became the Prague Gestapo police prison in 1940, the main fortress became the Ghetto in 1941

- Initial transport of Czech Jews, German and Austrian Jews in 1942, Dutch and Danish in 1943, various nationalities in the last months of the war as other camps were closed

- c. 141k Jews, inc. 15k children, held in the Ghetto 1941-1945. 33k died there (disease/malnutrition), 88k deported to Auschwitz, 23k survivors

This lies at the heart of his narrative. Austerlitz, as we discover gradually through the narrator’s irregular meetings with him, came to Britain on the Kindertransport from Prague in 1939, when he was not yet five years old. He was met at Liverpool Street Station by a couple, a minister and his wife from Wales, who fostered him, giving him a new name, and telling him nothing of his history. A teacher tells him his real name when he is in his teens, but rather than this prompting a search for his origins, Austerlitz turns away from his own past and consciously avoids any sources of information which might bring him too close to it. Thus, when he talks to the narrator about Breendonk, it is its history in the first, rather than the second war that he mentions.

Much later, after a strange encounter with his childhood self in the Ladies Waiting Room at Liverpool Street Station, by chance he hears a radio programme about the Kindertransport, and has a kind of epiphany, which prompts him to go to Prague and search for his family. He discovers that his father fled Prague for France, just ahead of the Nazi invasion, and that his mother, left alone there after the train had taken her child to safety, was deported to Terezin from where she was ‘sent east’, presumably to Auschwitz and presumably to her death.

Terezin shares many characteristics with other Nazi concentration camps. But there are elements of its history that mark it out. It was not a labour camp – it was presented as a ‘retirement settlement’ for elderly and prominent Jews, and its role was propaganda rather than economic, discouraging resistance to deportation with promises of comfort, and encouraging wealthier Jews to bring their valuables (of which, naturally, they were relieved on arrival). It was not a death camp – though the terrible conditions led to around 33,000 deaths from malnutrition and disease – but was a way station to Auschwitz. The particular make-up of the population of Terezin led to a rich cultural life, with music in particular playing a leading part.

However, the most notable feature of Terezin was that it was a ‘Potemkin village’, a place whose real purpose could be easily disguised. Indeed it was disguised in 1944, ready for a Red Cross visit, where it was presented as an ideal Jewish settlement. Overcrowding was addressed by the simple expedient of deportation, particularly of the less photogenic inhabitants, the old, sick and disabled. The place was cleaned up, shop fronts erected, and cultural and sporting activities organised for the prisoners. A film was made, which shows football matches and concerts, smiley, healthy looking people. The Red Cross appear not to have realised that they were being duped. Once they had left, of course, deportations were resumed.

W G Sebald, Austerlitz, pp. 266-68; H G Adler, Theresienstadt 1941-1945: The Face of a Coerced Community

‘I felt that the most striking aspect of the place was its emptiness, said Austerlitz […] the sense of abandonment in this fortified town, laid out like Campanella’s ideal sun state to a strictly geometrical grid, was extraordinarily oppressive, yet more so was the forbidding aspect of the silent facades.[…] What I found most uncanny of all, however, were the gates and doorways of Terezin, all of the, as I thought I sensed, obstructing access to a darkness never yet penetrated’

Austerlitz visits Terezin, having learned of his mother’s imprisonment there. He has been told that it is an ordinary town now, but he finds it strikingly empty, its streets deserted, its windows silent and blank. In its museum, he is confronted by the history he has been avoiding for so long – he studies the maps of the German Reich, in particular the railway lines running through them, that facilitated forced labour, deportations and genocide. The ground plan of the star-shaped fortifications is ‘the model of a world made by reason and regulated in all conceivable respects’, a fortress that has never been besieged, a quiet garrison for two or three regiments and some 2,000 civilians. But it seems to Austerlitz that, far from having returning to this civilised and reasonable state, the town is now filled with the people who had been shut in to the ghetto, as if ‘they had never been taken away after all, but were still living crammed into those buildings and basements and attics, as if they were incessantly going up and down the stairs, looking out of the windows, moving in vast numbers through the streets and alleys and even, a silent assembly, filling the entire space occupied by the air’.

Our human witness to Terezin is H G Adler, who, like Austerlitz, was born in Prague. He was sent initially to a labour camp in 1941, then to Terezin with his family in 1942. In 1944, he, his wife and her mother were deported to Auschwitz, where both women were murdered on arrival. Adler also lost his own parents and many other members of his family. From Auschwitz, he was deported to two successive sub-camps of Buchenwald before liberation. His research post-war focused on the archives of Terezin and formed the basis of his major work, Theresienstadt 1941-1945, which Sebald quotes and refers to extensively and which is still the most detailed account of any single concentration camp.

There’s one more fortress to consider. Kaunas, in Lithuania.

- 12 forts built in 19th century to defend against German armies

- All surrendered in 1914 and some fell into disuse

- Russians occupied in 1939 and used them as prisons

- 1941-45 German occupation: 7th fort used as concentration camp – 4k Jews killed there. 9th fort was execution and burial site for Jews from Kaunas and for other Jews shipped there during the Holocaust

- Abraham Tory reports in his ghetto diary that ‘single and mass arrests as well as “actions” in the ghetto almost always ended with a death march to the Ninth Fort, which in a way completed the ghetto area and became an integral part of it‘

We have no first-hand human witness here. Instead, we have Dan Jacobson, a South African writer whose book Heshel’s Kingdom describes his attempts to piece together a family narrative fragmented by history, the fate of whose members was determined by one event, the sudden death of Heshel Melamed in 1919, which freed his widow, children and grandchildren to emigrate from Lithuania to South Africa. Jacobson’s quest is to discover what happened to the other branches of the family, those who were left behind.

W G Sebald, Austerlitz, pp. 414-15, Dan Jacobson, Heshel’s Kingdom, pp. 159-62

Jacobson tells us that the Russians built a ring of twelve fortresses […] in the late nineteenth-century, which then in 1914, despite the elevated positions on which they had been constructed, and for all the great number of their cannon, the thickness of the walls and their labyrinthine corridors, proved entirely useless. […] In 1941 they fell into German hands, including the notorious Fort IX where Wehrmacht command posts were set up and where more than thirty thousand people were killed over the next three years.[…] Transports from the west kept ]coming to Kaunas until May 1944,[…] as the last messages from those locked in the dungeons of the fortress bear witness. One of them, writes Jacobson, scratched the words “Nous sommes neuf cents Francais” on the cold limestone wall of the bunker.

Neither Austerlitz nor the narrator visits Kaunas. But Austerlitz gives to the narrator, before he sets off to continue his own quest for answers, a copy of Jacobson’s book. Sebald’s narrative leaves us at the end of Jacobson’s Chapter 15, in an underground corridor where, behind glass, are preserved the ‘wall scratchings’ – literal marks of pain – of French Jewish prisoners brought here – after the war had effectively been lost. These include Max Stern, Paris, 18.5.44 – Sebald’s first name, and his date of birth; the fictional Austerlitz’s father’s first name, and last known location. What happened to these people, what happened to Jacobson’s family, cannot be known. Were they deported to an extermination camp – perhaps more likely, given the history of Kaunas, were they were killed right there?

Auschwitz is, of course, the fourth location that is implicit in the above.

It is both the archetype – we invoke this name above all others to stand for the Nazi machinery of mass murder – and the specific journey’s end for so many. Sebald doesn’t take us there though – it is present, always, but unseen and its name unspoken. We hear it only as an echo – in the name of our protagonist, in the mention of the Auschowitz springs which he visits at Marienbad. We don’t go there because we don’t need to – the phrase ‘sent east’ is already heavy with meaning.

Sebald gives us not only these closed places of death and terror but their apparent opposite – the transitory, liminal space of the railway station. Austerlitz’s fascination with the railway network was always tinged with a sense of loss, anguish even. In this, he reminds us of Max Ferber from Sebald’s The Emigrants who finds railway stations and railway journeys to be torture and who as a result, never leaves Manchester. And perhaps Sebald also was thinking of the passage in Elie Wiesel’s autobiography, concerning ‘those nocturnal trains that crossed the devastated continent’:

Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea

Their shadow haunts my writing. They symbolise solitude, distress, and the relentless march of Jewish multitudes towards agony and death. I freeze every time I hear a train whistle.

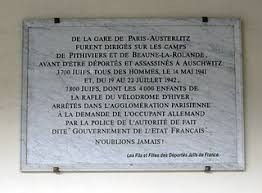

Towards the end of the narrative, at the Parisian railway station with which he shares a name, Austerlitz feels that he is ‘on the scene of some unexpiated crime’. Indeed, the Gare d’Austerlitz was the station from which Jews rounded up in the city were crammed into cattle trucks and transported to the transit camps near Paris – from where they were later crammed again into cattle trucks for transport to Auschwitz. And of course, one of the most often used images of Auschwitz itself is of the railway tracks.

Austerlitz pieces together his mother’s journey, after her partner and then her son leave.

She is ordered to report to the Prague Exhibition Centre with her belongings. She and her fellow deportees go to Holesovice station and from there by train to Bauschowitz station, from where they must walk to Terezin. From Terezin, at some unknown date, another train takes her to Auschwitz.

His father’s journey is more speculative. Austerlitz knows that Max flew from Prague to Paris. After that, his mother had various addresses for him in Paris, but no communications. Austerlitz wonders whether he was rounded up in 1941, in the first wave of arrests of foreign Jews, or in the much bigger round-up in July 1942, the Vel d’Hiv, the first round-up to take not only men capable of work but women, children, the sick, the elderly. Austerlitz also learns that Max may have been at one time at the Gurs camp in southwestern France, originally set up for Spanish refugees after Franco’s victory, but appropriated by the Nazis for Jews and members of the resistance. Did he die there, of disease or malnutrition? If not, was he deported from Gurs to Drancy and from there to Auschwitz? Or was he taken from the streets of Paris via the Gare d’Austerlitz to Pithiviers or Beaune-la-Rolande, and from there to Auschwitz? We take our leave of Austerlitz as he prepares to continue the search for evidence.

Sebald does recount another train journey. One which ended on the threshold not of death but of the hope of a new life. Austerlitz as a child travels from Prague’s Wilsonova station with the Kindertransport, a series of initiatives undertaken between Kristallnacht and the outbreak of war to get children, mainly Jewish, out of Nazi Europe – around 10,000 were thereby saved during that brief window of possibility. Jacques travels through Czechoslovakia and Germany, to the Hook of Holland, from where he takes the ferry to Harwich and another train to Liverpool Street Station. This is no fairy tale – for the fictional Jacques as for so many of the children, their assimilation and acceptance of their new home (a new language, new customs, often a new name, and a new religion) and their new family’s understanding of them, were problematic. And all of them faced traumatic absences, losses that they couldn’t grieve, and questions they couldn’t answer. Most never saw their parents again.

Austerlitz’s new life, the one that started on the platform at Liverpool Street Station, would never be free of those marks of pain. His academic quest to make sense of the family likeness between ‘monumental’ buildings, places that impose and imprison, and of the railway network that links them, has been superseded by the unrecognised need that had originally driven it. To find his family, to know everything he can know about their lives and their deaths, to inscribe those human stories, his human story, on the bricks and stones of the fortresses, prisons and railway stations that witnessed them.

(Austerlitz, p. 183)

‘I often wondered whether the pain and suffering accumulated on this site over the centuries had ever really ebbed away, or whether they might not still, as I sometimes thought when I felt a cold breath of air on my forehead, be sensed’

Bibliography

W G Sebald, Die Ausgewanderten (Fischer, 1992), English translation, The Emigrants, published 1996

__, Nach der Natur (Fischer, 1995), English translation, After Nature, published 2002

__, Austerlitz (Fischer, 2001), English translation published 2001

H G Adler, Theresienstadt 1941-1945: The Face of a Coerced Community (Cambridge UP, 2017)

Jean Amery, At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and its Realities (Indiana UP, 1980)

Dan Jacobson, Heshel’s Kingdom: A Family, a People, a Divided Fate (Hamish Hamilton, 1998)

Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea (Schocken Books, 1994)

Ten Books*

Posted by cathannabel in Literature on September 9, 2018

*Disclaimer – there are a lot more than ten books. I don’t automatically have a problem with compliance, but to attempt to distill 57 years of reading into just ten books would be just silly. Far harder, in a way, than the Ten Albums thing I did a while back.