Archive for category Literature

#Refugees Contribute – Judith Kerr

Posted by cathannabel in Literature, Refugees on June 14, 2015

Serendipitously, the start of Refugee Week 2015, with its theme of the contribution that refugees make to the communities in which they make their new homes, coincides with the 92nd birthday of Judith Kerr.

Her books were not part of my own childhood – I was too old by 1968 to enjoy The Tiger Who Came To Tea, and certainly by 1970 when the first Mog book appeared. But I read those books – again and again and again – to my own children. And unlike some books which I read to them again and again and again, which irritated me more with every rendition, it was always a joy to read anything by Kerr.

If pressed, I could probably still recite part of The Tiger, and certainly odd phrases from the Mog series (the cat who ‘forgot she had a catflap’, and who got an egg AND a medal after unwittingly foiling a burglary) have passed into our family language.

Nothing in the world depicted in these delightful stories suggests the circumstances in which Judith Kerr arrived in the UK. They’re not cloyingly cosy – after all, the final Mog book says a final goodbye to that forgetful cat. But one wouldn’t guess that her family had to leave their Berlin home suddenly in 1933, when the Nazis came to power, because her father had been openly critical of the party. He left first, having been tipped off that he was at risk, and her mother and the two children followed not long afterwards, travelling initially to Sweden and then to France, before applying for and being granted British citizenship. They could not have known in 1933 the full extent of the danger that they, as Jews, would have faced had they stayed, and they left France before that country ceased to be a safe haven, but as the war went on, Judith’s parents carried suicide pills with them, in case of a Nazi invasion.

Michael Rosen has suggested that the Tiger, who comes to tea and eats everything in the house, drinks all Daddy’s beer and all the water in the taps, was suggested at some subconscious level by the childhood awareness of an unexplained threat, that your home could be invaded, everything you have could be taken, without warning. That may be, and it’s certainly part of the unsettling charm of the book that we never forget that the Tiger is a tiger, that if not placated with all the food and drink he demands he could be dangerous. But at the same time, the willingness of the family to allow this unexpected visitor to empty their pantry conveys generosity and hospitality, along with imperturbability, rather than fear. It could be that this reflects the way in which parents maintain a calm unflappable air in order not to frighten children too young to understand real danger. But of course the Tiger leaves, of his own accord, and never comes back.

Kerr did write directly about her past, in three autobiographical novels collectively titled ‘Out of the Hitler Time’. She’s very conscious of her own good fortune, not only in that, unlike so many other families, they lost no one, but that they found a safe home and a welcome, and the chance to build new lives.

‘People here were so good to us in the war. It must have been awful for my parents, but when you consider what happened to the others who stayed behind, nothing bad happened to us. We didn’t lose anyone. All our family got out: my grandparents, uncles, aunts, they all got out. Nobody died. We had a terrible time with money, but so did lots of people, and people were very good to us wherever we went.’ (http://www.booktrust.org.uk/books/children/illustrators/interviews/104)

Happy birthday Judith Kerr, and thank you.

Books of the Year 2014

Posted by cathannabel in Literature on December 22, 2014

Inexplicably, the quality press has not yet invited me to name my top reads over the last twelve months, but no matter, I’ll do it anyway.

There is no attempt to rank or compare, or to identify one top title – just to share some of this year’s reading pleasure.

First, Taiye Selasi’s gorgeous Ghana Must Go. Drawn to it at first just for the title, I was blown away by the opening chapter, and as the narrative pulled back from that minute detail, that moment by moment evocation of a man looking out at his garden, realising that he is about to die, the breadth of the locations and the expanding cast in no way diluted the power of the writing. I did not realise at first that I was reading it aloud in my head, the way I read a novel in French, rather than hoovering up a page in one go as I normally do. In this case it wasn’t in order to understand it, but in order to feel the rhythm of the text. This is a poem as much as it is a novel.

John Williams’ Stoner had massive word of mouth before I got round to reading it. I was not disappointed – of course the academic milieu that it describes is very familiar to me and that helped to draw me in. But the emotional punch it pulled was unexpected and I rather regretted reading it in public.

I’ve written elsewhere about the final Resnick novel, Darkness, Darkness, from John Harvey. I read a lot of detective novels – it was a year of long train journeys – and discovered new writers, notably Ann Cleeves, Laura Lippman, Louise Doughty, Belinda Bauer and Anne Holt, as well as enjoying new stuff from existing favourite Cath Staincliffe. Her Letters to my Daughter’s Killer is powerful stuff.

Tiffany Murray’s Diamond Star Halo rocked my world, and Sugar Hall chilled my spine. I read the whole Game of Thrones series, and am eager for more. Other favourites from writers new to me were John Lanchester’s Capital, Patrick McGuiness’s The Last Hundred Days, and Sue Eckstein’s Interpreters. I will seek out more by all of them, though very sadly, Sue Eckstein’s early death means that there is only one more from her to look forward to.

Danny Rhodes’ Fan inspired me to reminisce and ruminate about my relationship with the game of football, and with Nottingham Forest in particular, and Caitlin Moran’s How to Build a Girl both made me laugh uproariously, and moved me to tears. It prompted a blog too.

As well as discovering new writers, I had the delight of reading more by some great favourites. Lesley Glaister’s Little Egypt, Stevie Davies’ Into Suez, Liz Jensen’s The Ninth Life of Louis Drax, all very different, and all on top form.

Lynn Shepherd’s latest literary mystery, The Pierced Heart, played beautifully with the Dracula myth, and the set up – a young man travels into the heart of Europe, an older, darker Europe, is welcomed by a mysterious Baron in a castle full of alchemical texts and other, more troubling collections – not only echoes Bram Stoker but reminded me of Michel Butor’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Ape, about which I hope to write something in due course. And oddly there were echoes of other aspects of The Pierced Heart in Stephen King’s excellent Revival, despite the very different setting. My most recent Doctor Who blog touched on these themes.

I didn’t expect Kenan Malik’s The Quest for a Moral Compass to be such a page-turner. I expected it to be enlightening and stimulating, sure, but it’s a huge achievement that it was genuinely difficult to put the book down. I wanted to find out ‘what happened next’, how through the centuries and the continents the human race grappled with the big questions of what it is to be good.

Other non-fiction that had an impact on me included Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave, which I read before I saw Steve McQueen’s harrowing and viscerally powerful film, and Dan Jacobson’s Heshel’s Kingdom, to which I was led by W G Sebald (in the final pages of Austerlitz). There was also Philippa Comber’s fascinating memoir of her friendship with Sebald, Ariadne’s Thread, another future blog, I hope.

Belinda Bauer – Blacklands, Darkside, Finders Keepers

Ann Cleeves – Dead Water, Red Bones, Silent Voices, Burial of Ghosts

Philippa Comber – Ariadne’s Thread

Stevie Davies – Into Suez

Louise Doughty – Apple Tree Yard

Sue Eckstein – Interpreters

Lesley Glaister – Little Egypt

John Harvey – Darkness, Darkness

Anne Holt – Blessed are Those who Thirst

Dan Jacobson – Heshel’s Kingdom

Liz Jensen – The Ninth Life of Louis Drax

Stephen King – Revival

John Lanchester – Capital

Laura Lippmann – The Innocents, Life Sentences, Don’t Look Back

Patrick McGuinness – The Last Hundred Days

Kenan Malik – The Quest for a Moral Compass

Caitlin Moran – How to Build a Girl

Tiffany Murray – Diamond Star Halo; Sugar Hall

Solomon Northrop – Twelve Years a Slave

Danny Rhodes – Fan

Lynn Shepherd – The Pierced Heart

Cath Staincliffe – Letters to my Daughter’s Killer

John Williams – Stoner

Blues for Charlie – on reading the last Resnick

Posted by cathannabel in Literature, Music on November 5, 2014

We go back a fair few years, Charlie and me. Pretty much instant, the connection, the attraction too. We had things in common – places (though I lived near Nottingham as a teenager, so my Nottingham wasn’t his – it was the Playhouse, Goose Fair, the City Ground, and the shops), music (listening to Miles as I write this), cats (ours was called Mingus. RIP), football (I was on the Trent End, still loyal to the Reds to this day, glory days long past, whilst he’s a County man).

Never very lucky in love, our Charlie. But attractive to women, no question. That crumpled, rumpled melancholy hard to resist – had we met in person, I’d have spectacularly failed to do so – but making it work in the long term, a lot tougher. He nearly found that, so very nearly, and it broke my heart when… but I won’t say, in case you don’t know, and if you don’t, you need to go back, as I’ve just done, to Lonely Hearts, and make his acquaintance for yourself, and follow him through the years, through to Darkness, Darkness.

I won’t say much about Darkness, Darkness, except that, as so many reviewers have already said, it’s a fitting coda to the series. It focuses on the miners’ strike – an event which still reverberates in Nottinghamshire and South Yorkshire, so that Nottingham football supporters still get called scabs by Yorkshire football supporters, though in both cases their parents were toddlers, if that, at the time of the strike – but it encompasses so much more. It’s an elegy really, a blues for Charlie.

So many of the cops whose investigations we follow on screen or on the page seem to be constructed according to a formula. A bit of (preferably traumatic) back story, a few quirks (an addiction, past or current, an obsession), and a tendency to go off piste, to break the rules. That can work – Rachel Bailey comes storming off the screen and the page (in Cath Staincliffe’s excellent novels) and into real life, so that when she (inevitably) does something monumentally daft, we, along with her long-suffering colleagues and friends, want to yell at her, shake her into common sense. The best ones, the ones we re-read even when we remember exactly who dunnit, where, why and how, turn that formula into someone we can invest in, not just in their ability to put the bad guy behind bars, but in their humanity, their vulnerability, their emotional life. And Charlie is one of the best, no question. Of course he has a back story (a broken marriage, nothing out of the ordinary), and a few quirks (his tendency to wear his most recent meal on his shirt front or his tie, for example). But he’s a rounded (and that’s not a crack about his waistline), nuanced, complicated character,

And so many of the narratives of crime and punishment that we consume rely on convoluted plots – plots not just in the sense of the narrative arc, but machinations, devilishly clever serial killers, hidden identities, etc. All very enjoyable, but bearing, one imagines, little relation to the day to day of policing. We suspend our disbelief, accept for the duration that in the picture postcard villages of Midsomer a deranged serial killer lurks behind every cottage doorway, or that the academics of Oxford are busier plotting their next murder than preparing their next research bid. The volume and the type of crime here is a tad more realistic, Charlie’s cases are more likely to involve cock-ups than conspiracies, individuals with chaotic lives committing chaotic crimes, often with consequences they could never have imagined. It’s not that there aren’t any serial killers, or any conspiracies, but they are interwoven with the mundanity, the banality, of ‘normal’ urban crime.

The other trope that those of us who watch the detectives can get a bit weary of, or even sickened by, is the reliance on sexual violence as a plot device. Again, this does feature in Charlie’s caseload over the years, as you’d expect. But there’s nothing sexy, nothing titillating here. The reality of rape and the fear of rape, the murky areas of human sexuality, the casual violence of language used towards women, are all shown clear-sightedly and compassionately, through Charlie’s eyes. It’s not that he’s so very PC. But his attractiveness to women isn’t just about his crumpled melancholy, it’s about his instinctive respect, his empathy. Even when he’s getting it wrong (as he does, often), fundamentally he’s a good man, someone you could lean on, trust. Those murky areas, and how fiction deals with them, are not just sub-text either – in both Living Proof and Still Water we confront them head on.

There’s so much humanity in these stories. And there’s music of course, flowing through them. There’s Millington’s regular assaults on the Petula Clark songbook, the bands at the Polish Club where Charlie dances with Marian, or the Otis Redding track that was playing when he met Elaine… But it’s the jazz that’s vital. It’s integral, it’s the atmosphere, those blue notes echoing Charlie’s melancholy, bringing out the noir on Nottingham’s mean streets. It’s the soundtrack to what we see of his life, to the daily grappling with petty crime, dysfunctional families, and the viciousness and brutality of which human beings are capable, and with the politics of policing, the admin, the power play. He goes home, and he finds a record, a track, that echoes his mood and as the music is described we can almost believe we’re hearing it too, the descriptions so vivid, so perceptive.

And so it seemed fitting, as I re-read the books, focusing less on the plot and more on the atmosphere, the background, the soundtrack, to put together a little playlist. One song for each novel. I hope Charlie would approve.

‘He’ll be okay. He’s got a flat white and yet another version of ‘Blue Monk’ to keep him warm’ (Darkness, Darkness, p. 416).

I’ll not worry about him then, and lord knows I have done sometimes, wondering if the sadness and the loneliness in him would take him over. But he’ll be okay. Cheers Charlie.

A Resnick playlist

Lonely Hearts (1989) Billie Holiday – (I don’t stand a) Ghost of a Chance (with you) (Music for Torching, 1955)

Rough Treatment (1990) Red Rodney Quintet – Shaw ‘Nuff (Red Rodney Returns, 1959)

Cutting Edge (1991) Art Pepper – Straight Life (Straight Life, 1979)

Off Minor (1992) Thelonious Monk – Off Minor (Monk’s Music, 1957)

Wasted Years (1993) Thelonious Monk – Evidence (Thelonious Monk at the Blackhawk, 1960)

Cold Light (1994) Duke Ellington Orchestra – Cottontail (The Carnegie Hall Concerts, 1943)

Living Proof (1995) Stan Tracey Duo – Some Other Blues (Live at the QEH, 1994)

Easy Meat (1996) Billie Holiday – Body and Soul (Body and Soul, 1957)

Still Water (1997) Miles Davis – Bag’s Groove (Bag’s Groove, 1957)

Last Rites (1998) Sandy Brown – In the Evening (In the Evening, 1970)

Cold in Hand (2008) Bessie Smith – Cold in Hand Blues (1925, The Bessie Smith Story, Vol. 3, 1951)

Darkness Darkness (2014) Thelonious Monk – Blue Monk (Thelonious Monk Trio, 1954)

http://www.arbeale.blogspot.co.uk/2014/10/thanks-john-and-charlie-for-great.html

Unconsoled and unsettled

Posted by cathannabel in Literature on April 17, 2014

It’s rare that I finish a novel that I really haven’t enjoyed and find myself obsessed with it. That’s what’s happened, though, with Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled. This is a novel I was strongly recommended to read, and I can see why. I can recognise its beauty and brilliance. I can recognise the things it has in common with works that I love and revere – Butor’s L’Emploi du temps, for example, and W G Sebald’s Vertigo, or The Rings of Saturn.

But the experience of reading it – I so nearly gave up. It was as if I was trapped in one of my own anxiety dreams. Knowing I need to be somewhere, that I’m responsible for something, and finding that time and space are conspiring against me. From the start, the protagonist appears to know, vaguely, that he is here (wherever that is) in order to do something important, but not precisely what, when, or why. As in dreams, the relationship of the people he meets to him and to each other shifts and some who appear at the start to be strangers to him become in the course of the novel his father in law, wife and son. Other people from his past appear, incongruously, whilst his parents, expected throughout the course of the narrative, are never encountered at all. Even the common feature of such dreams that one is inappropriately (or not at all) dressed occurs as Ryder is swept off to undertake high-profile public engagements in his dressing gown (the inappropriateness appears to go unnoticed by everyone else). I read on with such reluctance, fearing that Ryder’s experiences would find their way into and would amplify my own nightly unsettledness – and they did.

It also tied in spookily well with my ongoing fascination with labyrinths and mazes. The city in which Ryder arrives, ahead of his concert, is one in which you could walk in circles indefinitely, as Ryder himself notes. He encounters dead ends – a street blocked off by a brick wall, with no way around it and no opening, but which lies between him and his destination. He is constantly getting lost, his journeys taking him seemingly very far from his destination, only for him to realise he has come back to his starting point. The novel traces ‘an odd, sepulchral, maze-like journey’, through a ‘deterring labyrinth’. But it’s not just a static labyrinth or maze, as baffling and disorienting as they can be, because space is constantly distorting itself, like Butor’s Bleston, which ‘grows and alters even while I explore it’ (Passing Time, pp. 182-3).

But it was only after I had, finally, finished the book that I remembered that I had, some months previously, lent it to someone else, someone who suffers from serious problems with short-term memory, and increasingly with anxiety associated with that condition, needing frequent reassurance as what happened even ten minutes ago is lost in fog. I had wondered idly at other times what impact this would have on her reading – and she does read, making good use of her local library – surely after a few pages she would have forgotten what she had just read, and have to go back again and again, so that she would never actually finish the book? But this book … as she read it, did she recognise her own anxieties in its pages?

It seems to me that living with that kind of memory loss must be like a waking anxiety dream. To have, throughout the day, that sense that you are missing something, that you should be doing something, that you should be somewhere, and to be unable to retrieve the information with any sense of certainty… If you write things down, how do you know for sure whether the writing is telling you that something will happen, or that something has happened? As events from the past float into your memory you have no way of anchoring them in chronology, they could have happened yesterday, or months ago. The gaps are troubling so you may fill them with explanations that start off as speculation but become fixed as you hang on to them for reassurance that you know what happened really. And whilst sometimes you are anxious and you know that the cause of the fear is that your memory is so poor, at other times you don’t remember that you can’t remember, and deny that you need help and can’t see why people keep reminding you of things.

I can’t see that I will want to re-read The Unconsoled any time soon. It simply troubles me too much, taps too accurately into my own anxieties and insecurities, and into the fog of memory loss that I witness second hand. But it’s brilliant, and it’s still in my head, weeks after I reached the final page.

Butor at Belle Vue

Posted by cathannabel in Events, Michel Butor on March 8, 2014

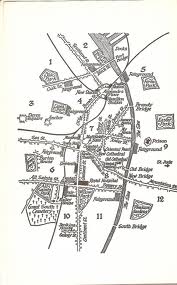

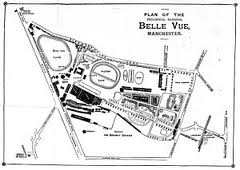

The long history of Belle Vue Gardens in Manchester is being celebrated this month, and it seems timely to note its appearance, under the name of Pleasance Gardens, in Michel Butor’s Manchester-inspired 1956 novel L’Emploi du temps (Passing Time).

Butor’s view of Manchester (Bleston in the novel) was, it must be admitted, largely negative. He loathed the climate, and the food, and seems to have been deeply unhappy in the city, where he arrived to take up the post of lecteur in the French department at the University in 1952.

He seems to have taken to Belle Vue, however. Pleasance Gardens, along with the various peripatetic fairs which rotated around the periphery of the city, on the areas of waste land, represent a mobile and open element in a closed, even carceral city, and a window on different kinds of community than those indigenous to Bleston. The narrator sees the friends he knows in a different light in these places, which may be in Bleston but are not fully part of it and don’t share its malaise.

Pleasance Gardens appears on the frontispiece map, in the bottom left-hand corner, its shape not dissimilar to that of the real Belle Vue. Butor took from the real city of Manchester the geography and architecture that interested him and that fitted with his narrative preoccupations, and ignored or altered the rest. The descriptions include a great deal of precision and detail – however, the historians of Belle Vue will have to judge where the fictional version departs from its model.

He describes the entrance to the Gardens:

The monumental entrance-gates whose two square towers, adorned with grimy stucco, are crowned … with two enormous yellow half-moons fixed to lightning conductors, and are joined by two iron rods bearing an inscription in red-painted letters beaded with electric bulbs then gleaming softly pink: ‘Pleasance Gardens’.

The big folding door which is armoured as if to protect a safe, and only opens on great occasions and for important processions, whereas we, the daily crowd, have to make our way in by one of the six wicket-gates on the right (those on the left are for the way out) with their turnstiles and ticket collectors’

The earthenware topped table which displayed, on a larger scale and in greater detail, with fresh colours and crude lettering, that green quarter circle with its apex pointing towards the town centre…

The tickets themselves are described in detail:

the slip of grey cardboard covered with printed lettering: On one side in tall capitals PLEASANCE GARDENS, and then in smaller letters: Valid for one visitor, Sunday, December 2nd. And on the other side: REMEMBER that this garden is intended for recreation, not for disorderly behaviour; please keep your dignity in all circumstances’

On this winter visit:

There was scarcely anybody in the big, cheap restaurants or in the billiard-rooms; avenues, all round, bore black and white arrows directing one to the bear-pit, the stadium, the switch-back, the aviaries, the exit and the monkey-house.

We walked in silence past roundabouts with metal aeroplanes and wooden horses, … and past the station for the miniature railway where three children sat shivering in an open truck waiting to start; and past the lake, which was empty because its concrete bottom was being cleaned’.

Posters everywhere echoed: ‘Come back for the New Year, come and see the fireworks’.

A later visit, in summer, followed one of the fires that feature so frequently in the novel. Belle Vue was devastated by fire in 1958, and whether this account was inspired by a real event I do not know – it may well be that whilst Manchester was plagued by an unusually large number of arson attacks over the period that Butor was there, he extrapolated from that to a fire at Pleasance Gardens, purely for narrative purposes.

In the open air cafe that is set up there in summer in the middle of the zoological section, among the wolves’ and foxes’ cages and the ragged-winged cranes’ enclosure, the duck-ponds and the seals’ basins with their white-painted concrete islands. I could see, above the stationary booths of this mammoth fairground, eerily outlined in the faint luminous haze, the tops of the calcined posts of the Scenic Railway, with a few beams still fixed to them like gibbets or like the branch-stumps that project from the peeled trunks of trees struck by lightning; and I listened to the noise of the demolition-workers’ axes’

If Butor generally warmed to the Gardens, his portrayal of the animals in the Zoo is less enthusiastic – he speaks of the cries of the animals and birds mingling with the noise of demolition, of melancholy zebras and wretched wild beasts, and of their howls during the firework display. Perhaps their imprisonment chimed uncomfortably with his own sense of being trapped in the city.

http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/nostalgia/way-were-belle-vue—1209695

Transformation of Sounds

Posted by cathannabel in Genocide, Music, Second World War, W G Sebald on January 25, 2014

W G Sebald describes, in his extraordinary novel Austerlitz, a recording of a film made at the Terezin concentration camp, as part of the effort to present it as a humane and civilised place to visitors from the Red Cross (overcrowding in the camp was reduced before the visit by wholesale deportations to Auschwitz, and once the visitors had left, remaining inmates were summarily despatched too).

In Austerlitz’s search for a glimpse of his mother, who had been interned there before her death, he slows the film down to give him a greater chance of spotting her fleeting image. This creates many strange effects, the inmates now move wearily, not quite touching the ground, blurring and dissolving. But:

‘Strangest of all, however, said Austerlitz, was the transformation of sounds in this slow motion version. In a brief sequence at the very beginning, … the merry polka by some Austrian operetta composer on the soundtrack … had become a funeral march dragging along at a grotesquely sluggish pace, and the rest of the musical pieces accompanying the film, among which I could identify only the can-can from La Vie Parisienne and the scherzo from Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, also moved in a kind of subterranean world, through the most nightmarish depths, said Austerlitz, to which no human voice has ever descended’. (Austerlitz, pp. 348-9)

The deception that the film sought to achieve is exposed.

The association between Terezin and music has another dimension, however. A remarkable number of inmates were Czech composers, musicians and conductors, and this, combined with the Nazi attempt to make the camp appear to be a model community with a rich cultural life, gave opportunities for music to be created and performed here. There is no easy comfort in this fact, when one knows that most of those who played, composed and conducted died here, or at Auschwitz, and that the moments of escape into this other world were few, and may in some ways have made the contrast with the brutality and barbarism of the regime even harder to bear.

The music of Terezin, however, now reaches new audiences through performance and recordings. Each time we hear the voices of those the Nazis sought to silence, that is a small victory.

Czech conductor Rafael Schachter – transported to Terezin in 1941, organised a performance of Smetana’s The Bartered Bride and finally of Verdi’s Requiem, performed for the last time just a few weeks before his transfer to Auschwitz in October 1944

Jazz musician and arranger Fritz Weiss – arrived in Terezin in 1941, set up a dixieland band called the Ghetto Swingers. Fritz was sent to Auschwitz in 1944, with his father, and was killed there on his 25th birthday.

Viktor Ullmann – Silesian/Austrian composer, pupil of Schoenberg, was transported to Terezin in 1942. He composed many works there, all but thirteen of which have been lost, before being transported to Auschwitz in 1944, where he was killed.

Gideon Klein – Czech pianist and composer, who like Ullmann composed many works in the camp as well as performing regularly in recitals. Just after completing his final string trio, he was sent to Auschwitz and from there to Furstengrube, where he died during the liquidation of the camp.

Pavel Haas – Czech composer, exponent of Janacek’s school of composition, who used elements of folk and jazz in his work. He was transferred to Auschwitz after the propaganda film was completed, and was murdered there.

Hans Krasa wrote the children’s opera Brundibar in 1938, and it was first performed in the Jewish orphanage in Prague. After Krasa and many of his cast were sent to Terezin, he reconstructed the score from memory, and the opera was performed there regularly, culminating in a performance for the propaganda film. Krasa and his performers were sent to Auschwitz as soon as the filming was finished, and were gassed there.

Not all of the musicians of Terezin were killed. Alice Herz-Sommer survived, along with her son. Now 110, Alice sees life as miraculous and beautiful, she has chosen hope over hate.

“The world is wonderful, it’s full of beauty and full of miracles. Our brain, the memory, how does it work? Not to speak of art and music … It is a miracle.”

http://www.terezinmusic.org/mission-history.html

http://www.theguardian.com/music/video/2013/apr/04/holocaust-music-terezin-camp-video

http://holocaustmusic.ort.org/places/theresienstadt/

http://www.theguardian.com/music/2006/dec/13/classicalmusicandopera.secondworldwar

http://www.haaretz.com/weekend/week-s-end/i-look-at-the-good-1.261878

http://claude.torres1.perso.sfr.fr/Terezin/index.html

http://www.musicologie.org/publirem/petit_elise_musique_religion.html

2013 – the best bits. And some of the other bits.

Posted by cathannabel in Events, Film, Literature, Music, Personal, Television, Theatre on December 31, 2013

It has been a funny old year. Funny peculiar, though not without the odd moment of mirth and merriment along the way.

I came back from one secondment to my regular job in January, and went off on the next secondment in December. This new one is a major change – working for HEFCE, based at home when not attending meetings in various exotic parts of the UK (oh, OK then, Croydon, Birmingham, Manchester, Dorking…). It’s a fantastic opportunity, and challenges the way I organise my life as well as requiring me to acquire new knowledge and new skills.

I graduated, again. Did the whole gown and mortar board thing which I hadn’t been fussed about when I was 21 and graduating for the first time. And then, with barely a pause, on to the doctorate. Studying part-time, it’s going to be a long haul, with who knows what possibilities at the end of it, but I’m loving it.

In February, a beloved friend and colleague died, and we – his family, friends, colleagues, students – grieved but also worked together to put on an amazing event in his honour, the 24 Hour Inspire. We raised money for local cancer charities, and have raised more since, through an art exhibition, plant and cake sales and various 10k runs/marathon bike rides, etc. And we’re now planning the 24 Hour Inspire 2014, and the publication of Tim’s diary. He will continue to inspire.

Culturally, my high points in 2013 have been:

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie at the Showroom, talking about Americanah, and Half of a Yellow Sun

- Peter Hill premiering newly discovered/completed Messiaen at the Upper Chapel (and playing Bach, Berg and Schoenberg too)

- Arnie Somogyi’s Scenes in the City, playing Mingus at Sheffield Jazz

- Tramlines – the Enid in the City Hall, Soukous Revelation in the Peace Gardens, Jim Jones Revue and Selecter at Devonshire Green. (And more, but those were the absolute top bits).

- The 24 Hour Inspire – 24 hours of lectures on life, the universe and everything, including Ed Daw’s blues piano, Rachel Falconer on poetry and birds, Jenny Saul on implicit bias, Claire McGourlay on the Innocence Project, and personal narratives from Brendan Stone and Elena Rodriguez-Falcon. Plus John Cockburn’s rendition of (What’s so Funny ’bout) Peace Love and Understanding, and my favourite Beatles B-side, Things we Said Today, and more busking from Mike Weir, Graham McElearney and Eugenia Chung. And more, lots more.

- Fabulous Beethoven quartets/quintet from the Elias at the Upper Chapel

- A magical Winter’s Tale at the Crucible

- Two awesome Britten operas (Peter Grimes and Death in Venice) from Opera North at Leeds Grand

- New (to me) authors enjoyed this year: Maggie O’Farrell, Louise Doughty, Lucy Caldwell, C J Sansom, Alison Moore, Edward St Aubyn, Rebecca Solnit, Wilkie Collins, Jonathan Franzen

- Wonderful new books from authors I’ve enjoyed before: Stephen King’s Dr Sleep and Joyland, Lynn Shepherd’s A Treacherous Likeness, Jon McGregor‘s This isn’t the Sort of Thing…., Robert Harris’s An Officer and a Spy

- Finally finished Proust’s Sodome et Gomorrhe. Allons-y, to La Prisonniere!

- I’ve learned to love Marvel superheroes (Avengers Assemble! Thor! Iron Man! Agents of Shield!), and have thrilled to The Walking Dead, Orphan Black (virtuoso performance(s) from Tatiana Maslany), Utopia and, of course, Dr Who.

- Speaking of which, not only an absolutely stonking 50th anniversary episode, but also a fascinating and very touching drama about the show’s early days, with David Bradley as William Hartnell, the sweet and funny The Five-ish Doctors, with Peter Davison, Sylvester McCoy and Colin Baker sending themselves and everyone else up with great affection, and Matthew Sweet’s Culture Show special. And the Christmas episode…

- Other cracking telly – Broadchurch, Homeland, Misfits, The Fall, Southcliffe, The Guilty, The Americans… And from across the Channel, not only another masterclass in French profanity from Spiral, but the wonderful The Returned

- And other top films – Joss Whedon’s Much Ado, Lore, The Hobbit Pts 1 & 2, Lincoln, and Patience (after Sebald).

About the blog itself. It’s been less focused on my areas of research recently, and that will continue to be the case, as I’m working on the PhD. The odd digression will find its place here – as Tim used to say, tangents are there to be gone off on, and the blog is a good way of nailing those (to mix my metaphors somewhat) and stopping them from distracting me for too long. I shall be continuing to go on about all sorts of other things that pique my interest. In particular the blog will continue to be a place where refugee stories are foregrounded, as a riposte to the mean and dishonest coverage which those stories tend to receive.

Over the last year, my posting has been somewhat erratic. I note that I didn’t write anything between March and June (I made up for it in June, however, with a Refugee Week blog-blitz, as well as a piece about Last Year at Marienbad which I still intend to follow up. That hiatus may have had something to do with being in the final stages of my degree – finishing off my dissertation, and a last batch of essays and presentations.

There are so many fantastic bloggers out there, too many to do justice to. We lost one this year, as the great Norman Geras passed away. But I’ll continue to enjoy, and to share/reblog That’s How the Light Gets In, Nowt Much to Say, and Futile Democracy, amongst others. For my research interests, I will no doubt continue to find lots to think about and follow up in blogs from Decayetude and Vertigo.

So, thanks to the aforementioned bloggers, to the various people with whom I’ve shared the cultural delights enumerated above, to friends and family who’ve supported me in my ventures and refrained (mostly) from telling me I’m mad to try to do so many things.

Thing is, I have a history of depression. I know that the best way for me to fight that, to avoid sliding back into that dark pit, is to do lots of stuff I care about. So, not just the job – which I care about, passionately – and my wonderful family, but research, writing, ensuring that we do Tim proud via the charity, and so on. I am very aware that there’s a tipping point, that if I do too much stuff I care about, given that I also have to do stuff that I have to do, just because I have to do it, the anxiety of having so much going on can itself lead to sleepless nights, which make me less able to cope, thus leading to more worrying and so on and on… It’s all about balance, and about having support when I need it. So, to all of you who, whether you know it or not, provide that support, and help me to keep that balance, a heartfelt thanks.

In particular, over this last year, I’d like to thank:

For unstinting support and encouragement through the part-time degree and especially as I reached the final stages – tutors Sophie Belot and Annie Rouxeville, and classmate Liz Perry. And a special thanks to Chris Turgoose for ensuring that my graduation gown stayed put via an ingenious arrangement of string and safety pins.

For support and encouragement to go on to the PhD – the aforementioned Sophie, Annie, and Liz, plus Rachel Falconer, Helen Finch, and my supervisors Amanda Crawley Jackson and Richard Steadman-Jones

For their contributions to the work of Inspiration for Life, and the 24 Hour Inspire, and their support in commemorating and celebrating Tim – Tracy Hilton, Ruth Arnold, Vanessa Toulmin, Chris Sexton, John Cockburn, Lee Thompson, Matt Mears and David Mowbray

My family, of course, without whom…

And, finally, Tim. I’d have loved to share this year’s triumphs and tribulations with him.

Have a wonderful 2014 all of you.

Sebald’s Bachelors

Posted by cathannabel in W G Sebald on September 19, 2013

Terry Pitts’ Vertigo blog reviews a fascinating and important new study of W G Sebald by Helen Finch.

Part of the disorientation of Sebald’s characters can be viewed as precisely an attempt to go astray, to resist compulsory heterosexuality and to transgress the borders of Germany and Europe in search of a queer affinity that might provide a source of resistance to the straightening and oppressive orientation of bourgeois society and family.

Helen Finch’s new book Sebald’s Bachelors: Queer Resistance and the Unconforming Life is an ambitious, thin book that contains a dense, closely argued “queer reading of Sebald’s work.” The result is one of the most important books on Sebald to date. I am sure that there are a number of Sebald readers, casual and otherwise, who will look askance at a queer reading of his work, but, as Finch demonstrates, the clues – both obvious and coded – are there in plain sight. And keep in mind Finch’s careful caveat: “this study confines itself to…

View original post 1,113 more words

From La Banlieue de l’Aube à l’Aurore (The Suburbs from Dawn to Daybreak) by Michel Butor with Translation by Jeffrey Gross

Posted by cathannabel in Literature, Michel Butor on September 15, 2013

From Gwarlingo, a translation of a Butor poem, with a link to a whole collection of them. A wonderful find – especially as so little of Butor’s work is available in English.

In the midst of life, we are in death, etc…

Posted by cathannabel in Literature, Television on August 14, 2013

…. and nowhere more so than in the haunting (in so many ways) French drama The Returned which recently left viewers on tenterhooks (or alternatively furious and vowing never to darken its doors again) with a final episode that left more questions than answers, and a long wait for series 2.

The dead return, apparently unchanged (at least initially), and unaware of their deadness. Camille walks through her front door as if nothing untoward had happened (she’d died in a coach accident a couple of years previously), demanding food and complaining bitterly that her room has been rearranged. There’s no overt horror in her re-appearance, which allows a much more subtle take on its effects upon her family. The pattern is repeated elsewhere as the newly undead attempt to find their old lives and slip back into them, only to be confronted by the fact that other lives have moved on in the meantime.

Where do these revenants fit in, in the literature and mythology of the undead? They are not ghosts, which tend to be seen only fitfully and not by all, and to have no physical substance – Camille and her fellow returners are absolutely here, physically, ravenously hungry and startlingly randy too. Ghosts often have a purpose too – like Banquo they are here to shake their gory locks at those responsible for their untimely demise, or to seek a way of resolving their unfinished business in this world – but if these have a purpose it’s not clear what it might be – at least not yet. They are not zombies, whose physical substance has been reactivated without the personality, the mind, the soul (if you will) that previously accompanied it – an ex-person, reduced to a body and a hunger – these returners know who they were, who they loved, and have the full range of human thought and emotion.

Dramatically, there is much that recalls those stories of individuals believed to be dead, and reappearing unexpectedly to cause consternation and conflict as they try to reclaim their lives (Balzac’s Colonel Chabert, Martin Guerre, Rebecca West‘s Return of the Soldier). However, Rebecca West’s returning soldier and Balzac’s Colonel Chabert are not instantly recognisable as the people they once were. Chabert, who has clawed his way out of a mound of corpses, looks like what his former wife would wish to believe he was, a madman and an imposter. Those who made their way home across Europe, as he did, over a century later, were often changed beyond recognition too, their health (mental and physical) permanently damaged, skeletal and haunted both by what they had witnessed and by their own survival. The return of the deportees was a ‘retour a la vie’, and some at least, with care and medical treatment, did begin again to resemble their previous selves. Like Dickens’ Dr Manette, ‘recalled to life’ after years of incarceration, and gradually establishing a fragile hold on life again.

In The Returned, Camille’s father says to his estranged wife Claire that ‘you prayed for this’ – it’s an accusation rather than a statement, even though in his own way he too had sought a continuing connection with the daughter he’d lost. That reminded me of the episode of Buffy (‘Forever’, Season 5), where Dawn attempts to use witchcraft to bring back her mother, realising as she hears the footsteps approach the door that what has come back will not be the person she is grieving for. She breaks the spell, just in time. This thread is picked up in the following season as Buffy herself crosses back over that threshold between death and life, and feels that she isn’t quite as she was, that she has ‘come back wrong’.

Stephen King explored this too, in Pet Sematary, where the knowledge that one could bring back the deceased is too powerful for the protagonist to resist, even having tested the water, as it were, with a cat (who most decidedly isn’t the creature it was before)

and in the madness of terrible loss and grief does not turn back as Dawn did from bringing back his lost son. The returned in King’s narrative look and sound almost like themselves. Almost. They know stuff though, that they should not know, and they are malign, clearly demonic. Some of The Returned’s revenants seem to know stuff in the same way and to be able to use their knowledge to challenge or goad the living. But whether they are on the side of the angels I would not want to say. Ask me in a year or so, when I’ve seen Season 2.

The Returned‘s revenants were not (despite Claire’s prayers) brought back by the living, they appear to have simply returned. But throughout literature the appearance of the dead amongst the living has always been associated with a threat – with the terror or destruction of the living, or with the exposure of past crimes and injustices. Or, at the very least, the confrontation of the living with the trauma of death, in the person of those who have inhabited the liminal space between death and life. Thus neither the unexpectedly alive nor the undead can simply be reintegrated into society, even if the living can accept them. They haunt us, and are themselves haunted,

What these various narratives address is the sense of unfinished business that is inevitably part of bereavement, and the notion that death is a threshold that might, just, be permeable. There’s a moment in an otherwise entirely negligible children’s film, Caspar the Friendly Ghost (yes, I know, bear with me) where the dead mother entreats her husband and daughter: ‘I know you have been searching for me, but there’s something you must understand. You and Kat loved me so well when I was alive that I have no unfinished business, please don’t let me be yours.’ That one line justifies the existence of the film, for me. Because so many of these narratives are really about how impossible it is for the living to deal with death.

Which takes me back to Buffy, and the extraordinary words that Joss Whedon puts into the mouth of Anya (she’s a thousand-year-old vengeance demon, but don’t worry about that, the point is that she says the stuff that we feel, and think, but don’t say):

I don’t understand how this all happens. How we go through this. I mean, I knew her, and then she’s – There’s just a body, and I don’t understand why she just can’t get back in it and not be dead anymore. It’s stupid. It’s mortal and stupid. And – and Xander’s crying and not talking, and – and I was having fruit punch, and I thought, well, Joyce will never have any more fruit punch ever, and she’ll never have eggs, or yawn or brush her hair, not ever, and no one will explain to me why. (‘The Body’, season 5)

So the unfinished business is not theirs, but ours. And they come back, in dreams, but we know that their presence is not quite right, that time is out of joint if they are here. I’ve dreamed so often that my mother is alive. But never without that sense of unease, which could not be further from the feeling that I associate with her, of warmth and comfort and of being loved. She has gone, and we haven’t got over it, and we won’t, but we know it is real.

Still, that boundary, that threshold, is always disturbingly present, just on the edge of our field of vision, and so we will continue to be fascinated by the notion that sometimes they do come back, and how that might be, even if it is and will always be the stuff of nightmares.

Related articles (beware spoilers)

- The Returned (2004) (rantbit.wordpress.com)

- http://lesrevenants.canalplus.fr/#!/

- some further thoughts on Colonel Chabert here: https://cathannabel.wordpress.com/2013/01/20/sebald-and-balzac-quests-and-connections/