You Reds

Posted by cathannabel in Football on December 22, 2016

In all of the words I’ve churned out about 2016, I haven’t talked about football. Whilst it was, indeed, a reason to be miserable, it seemed inappropriate to mention it alongside Aleppo, Trump and Brexit. And frankly there was nothing to celebrate alongside the brilliant films, books and so on that I have recommended to anyone who’s interested.

Supporting Nottingham Forest has provided very few reasons to be cheerful in recent years. I have the advantage over my son, in that my years as a Red have included the glory years, the miracle years, celebrated in Jonny Owen’s film, I Believe in Miracles. The best we’ve seen in his years as a Red has been promotion from League 1 to the Championship, notwithstanding the odd good game along the way. We’ve appointed and disposed of many managers, some with good reason, others quite arbitrarily.

I’ve only managed to get to two games so far this season. I saw them defeated away at Hillsborough, after being one up at halftime, and I saw them beaten 2-0 at home by Wolves. The latter was quite the worst performance I can recall.

So what can I salvage from a dismal year? What reasons can I find to be cheerful or at least hopeful? The change of ownership may well prove to be positive, but we’ll have to wait and see. And whether with the new owners we have yet another change of manager, and whether that is a good or bad thing – well, the jury’s out. Should they give him time, particularly given the appalling injury problems he’s had to contend with, or has he already had enough time and failed to prove that he has a grasp of strategy or the ability to get the best out of the players?

Dunno.

But what I do take away from this year is not anything that happened on the pitch. It’s about what it is to support a team through thick and thin, through glory days and the slough of despond. It’s about the rueful camaraderie between people who support crap teams, whether they’re crap teams who were once brilliant, or crap teams who’ve always been that way. Last Saturday summed that up for me.

Firstly, Forza Garibaldi. This group of Forest fans, proper, Forest ’til I die, couldn’t change it if I wanted to, Forest fans, organised a very jolly Xmas pre-match meet up in a Nottingham pub, raising funds for Archie’s Smile, a charity supporting kids with Downs, including one Tyler Cove, whose joyous presence lit up the whole event. There were Wolves fans there too, who joined in with enthusiasm, sending themselves up and engaging in some competitive ‘we’re shitter than you’ sing-songs which kind of sums up what it’s like being a football supporter outside the top echelons of the Premier League.

Forza’s mission is to

mobilise ourselves into creating a positive, enjoyable occasion around NFFC games both home and away. And, crucially, to harness that into improving the atmosphere and backing of the team. The objective is to create a platform that galvanises the fanbase into wanting to offer their support.

So, how do we do this?

We don’t pretend to have all the answers or a full strategy but our starting point is to get people together before games and create something, a ‘buzz’ if you will. We will do this via mass gatherings at various locations and occasional specialised events with the theme always being that we inject a degree of adrenaline into proceedings. We hope that fervour and passion is then carried beyond the turnstile.

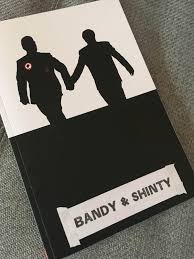

Secondly, Bandy & Shinty. I’ve found much pleasure in recent years in reading some excellent Forest-focused blogs. Now there’s a fanzine, its second issue published just a couple of weeks ago, which features fascinating articles on a range of Forest topics, with an incredibly high standard of writing, and beautifully produced. Copies were very much in evidence at the Forza jollification and I understand they are selling fast.

After the Forza do there was some frankly inept and half-hearted messing about on the pitch, and a well-deserved defeat for the Reds. I will let other pens dwell on that misery. After the final whistle we headed home on the train. A couple of Wolves fans just across the aisle, and then at Chesterfield we were invaded by a horde of jubilant Bolton fans, singing ‘Up the football league we go’. We all assumed they’d won, but apparently not. They’d travelled all the way to Chesterfield, been beaten, but were having a half-decent season and so were in tremendously good spirits. We ended up talking to the Wolves fans, and one of the Bolton fans, and it was all rather jolly.

Years back, I would have been nervous, would have been tensed for the atmosphere to turn nasty. Instead there was that rueful camaraderie.

I’d love Forest to win, I’d love another miracle. But I’d settle for staying where we are – no promotion, no Cup runs – if when the team came out on to the pitch we knew that they cared about the team, wore the shirt with a sense of its history and of how important it is to the fans, did their best, every time. And that the manager had a sense of how to get the best out of all of those players, in terms of motivation and also what Clough did so supremely, to spot what they could do best and then focus them relentlessly on doing that, just that, until they were unbeatable.

Maybe next year.

Forest ’til I die, couldn’t change it if I wanted to.

Youuuuuuu Reds!

2016 – what the actual??

Posted by cathannabel in Africa, Events, Politics, Refugees on December 15, 2016

It’s been a funny old year. Not so much of the ha ha, either. Is there anything to be said that hasn’t already been said, better probably? I doubt it, but I can’t write about the books, films and other cultural pleasures of the year without acknowledging the seismic changes and alarming portents that it has presented.

Reasons to be Miserable:

Daesh initiated or inspired terrorist attacks clocked up more deaths and more terrible injuries than the mind can encompass. As always, most of these were Muslims, in Muslim countries, although our news media inevitably foregrounds the attacks in France, Belgium and the USA. As appalling as those murders were, on my very rough calculations, Iraq was the worst hit, with over 450 deaths, followed by Pakistan. I tweeted the names of the dead from Brussels, Nice and Orlando, but will never know the names of most of those murdered in Kabul, Istanbul, Jakarta, Baghdad, Ouagadougou, Quetta, Grand Bassam or Aden.

According to the UNHCR, the number of migrants dying whilst crossing the Mediterranean reached 3800, a record. Fewer are making that journey, but they are making it via the more perilous routes and in flimsier boats. Worldwide, over 65 million people are forcibly displaced, over 21 million are refugees, and 10 million stateless. The vast majority of those displaced are hosted in neighbouring countries in Africa or the Middle East. Six per cent are in Europe. Over half of the world’s refugees came from just three countries – Afghanistan, Syria and Somalia.

With regard to Syria, anything I say here may be outdated before I press Publish, but there can be no doubt that we are seeing one of the greatest tragedies of our times unfold, and that war crimes are happening there which will be remembered with shame and horror.

I’ve been told to shut up about Brexit, that the people have spoken and they’ve said we must leave Europe and that’s that. As if democracy means that once the votes are counted, those whose views did not prevail must be silent or be regarded as traitors, as if, had the vote gone the way everyone (including Farage and Johnson) expected it to, they would have shut up and let ‘the will of the people’ prevail. Firstly, whilst a majority of those who voted said we should leave Europe, that is all they said. They were not asked and so they did not vote on whether we should leave the single market, what should happen about immigration controls, what trade agreements should be in place outside the EU, what would happen to EU citizens based in the UK or vice versa, what would happen to those employment and wider human rights and other legal provisions currently under the EU umbrella. And so on. All of that has now to be negotiated and worked out, and that’s a job for Parliament. How else could it possibly happen? If anyone thinks they understand how the EU works and thus what are the implications of hard or soft Brexit, they need to read Ian Dunt’s book – Brexit- What the Hell Happens Now? Dunt isn’t talking about the arguments pro or con Brexit, but about what could happen now, what the options are, what the most likely consequences of each option are, and so on.

The US election outcome was described to me by an American colleague recently as ‘somewhere between a mess and a catastrophe’. I am (for once) holding back from comment – I know how deeply this is felt by US friends, some of whom are now seeing fault lines in their families and friendships as some support what others find inexplicable and irrational. We’ve seen a bit of that here since June. A left-wing Brexiter said to me recently that his view was that the EU was so compromised and corrupted that we had to break it in order to fix it. My fear is that some things that get broken simply can’t be mended. Something of the same feeling seems to have prevailed in the US – and that’s one of the reasons why the arguments against Trump failed to stop him winning.

This is the year when I’ve felt closest to despair, for all the above reasons, and because the Labour Party, which I’d thought was my natural home politically, has been so ineffectual in opposition. I took the hard decision to resign my membership – I doubt that I will join another party, perhaps I have to accept that there is not, and never will be, a political party to which I could sign up without caveats and qualms. In that case I have to be led by my principles and values and be willing to back, vote for, work with those politicians and activists who seem closest to them, whether they be Labour, Green, Lib Dem, Women’s Equality or any combination of the above.

On the other hand…

The Hillsborough inquests returned their verdict, and concluded that planning errors, failures of senior managers, commanding officers and club officials, and the design of the stadium, all contributed to the disaster. The behaviour of fans did not. Thus the tireless, dignified campaign fought by the families, survivors and their supporters, was finally vindicated, fully and unequivocally. Read Phil Scraton’s Hillsborough – The Truth, updated in light of the inquest verdict, and Adrian Tempany’s account of that day and what followed, and his excellent book exploring the broader picture in contemporary football, And the Sun Shines Now.

Too early to say whether Standing Rock will turn out to be a victory for the Native American and other environmental protestors – but it was truly remarkable to see the army veterans who had joined them on the site asking for and receiving forgiveness for the long history of oppression and genocide against the indigenous peoples.

Too early to say, too, whether Gambia has taken a historic step towards democracy, or wheher the defeated dictator will be successful in his attempts to overthrown the result of the election. (Meantime in Ghana another peaceful general election brings about a change of government ).

Too early to say whether hard right parties in Europe will prevail, or whether the tide will turn against them before people go to the ballot, but at least the Austrian electorate rejected the Freedom Party’s presidential candidate in favour of a former leader of the Greens.

If 2016 leads us to expect the worst (after two nights spent sitting up waiting for election results which delivered the outcome we feared most, against the predictions of the pundits), then we have to remember that this does not mean that the die is irrevocably cast.

So, reasons to be anxious, reasons to be angry, reasons to be sad – but not reasons to lose all hope.

I’ve tried, throughout this hard year, to hold on to my own brand of faith. It’s not been easy, and it won’t be easy.

In all of this, though, I have found joy in family and friends, in working for Inspiration for Life and in our extraordinary 24 Hour Inspire, in books and film and music and theatre and opera and TV, in my PhD research, in walking in the lovely countryside on our doorstep. I’m bloody lucky, and I do know it.

If I’m going to sum up, somehow, what I want to say about 2016, I think I will leave it to Patti Smith, singing Bob Dylan’s A Hard Rain, at the Nobel Prize ceremony. She stumbled, apologised, and began again. In her performance, and in Dylan’s song, there is humanity and hope.

2016 in TV, theatre and music

Posted by cathannabel in Music, Television, Theatre on December 13, 2016

I’m very conscious that I’ve watched very few of the series which are getting the Best Of accolades from the quality press. Some of them are sitting on our BT Vision box waiting to be watched, others we didn’t catch on to until they were underway and so are now waiting for the repeats.

Some of what we did watch was old stuff, the crime series that circulate on the Drama channel or ITV3, of which the best was undoubtedly Foyle’s War, for its meticulous attention to historical detail and the wonderful, understated central performance by Michael Kitchen.

We came late to the Scandi party, having missed The Killing altogether, and caught up with the Bridge only on the most recent series, but did enjoy Follow the Money (financial shenanigans), Blue Eyes (politics and right-wing terrorism), Trapped (murder, human trafficking and a heck of a lot of snow). And whilst we wait for Spiral to return, we saw its late lamented Pierre being an unmitigated shit in Spin.

We enjoyed the latest series of Scott & Bailey, Shetland and Endeavour. But the prize here goes (again) to Line of Duty. Vicky McClure and Keeley Hawes were both formidable and the tension brilliantly ramped up.

The Returned returned. Series 2 was as full of mystery and atmosphere as Series 1 and thankfully did not feel the need to offer tidy solutions. It left loose ends, but in a way that suggested the cyclical nature of events rather than anything that could be resolved by a third series.

Orphan Black’s penultimate series was as always thrilling and funny and complicated, with Tatiana Maslany triumphantly playing multiple roles, with such confidence and subtlety that I still occasionally forget that it’s all just her.

The Walking Dead ended its last season on a horrific cliffhanger, and the opener was pretty grim as well. I have doubts about the series – it is inevitably repetitive: our group finds what looks like a haven, the haven is compromised/invaded, a few of our lot are offed, a few new bods tag along, and on they go to the next apparent haven. The big shift is that as the series have progressed, the greatest danger is no longer from the walkers, since their behaviour is predictable and the survivors have developed effective tactics for defence and despatch, but from other more ruthless survivors. This is interesting territory (the walkers themselves are pretty dull, after all), but I’m not convinced by the way the writers are handling the current storyline. And they’ve shown a worrying tendency to make people act out of character, to do utterly stupid things that they know are utterly stupid, in order to move the story along. So, the jury is out, but I will be watching, whatever.

We also thrilled to The Night Manager, London Spy and Deutschland 83, and to the latest adaptations of War and Peace, and Conrad’s The Secret Agent.

The A Word was wonderful – I know that parents of autistic children had some quibbles, particularly about the way in which children who are ‘on the spectrum’ so often are shown as having special abilities, like Joe with his encyclopaedic knowledge of 80s pop, which is not always the case. But this was the story of one child, and his extended family. The performances were superb, the writing subtle and nuanced, and the image of Joe marching down the road, earphones on, singing ‘World Shut Your Mouth’ or ‘Mardy Bum’, will stay with me for a long time.

Raised by Wolves had a splendid new series, and then was inexplicably and inexcusably cancelled. Still hoping that Caitlin Moran’s crowdfunding project gets sufficient support to bring it back.

Normally my TV of the year would include Doctor Who, but we’ve had a hiatus this year, and will have to wait till Christmas Day for the special, and then 2017 for a new series (and a new companion). Meanwhile there was Class, on BBC3, which got off to a promising start, but as I’ve only seen 3 episodes so far, all comment and judgement is reserved until we’ve caught up.

At the theatre this year we saw two Stage on Screen performances at the Showroom – the Donmar Warehouse production of Liaisons Dangereuses, with Dominic West and Janet McTeer, and Anthony Sher’s magnificent and heartbreaking Lear.

Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen at the Lyceum Theatre in Pinter’s No Man’s Land were deeply unsettling as well as darkly funny.

And we saw a glorious reimagining of The Duchess of Malfi, transported to West Africa, as Iyalode of Eti.

Opera North at Leeds Grand Theatre – Andrea Chenier, Giordano’s French Revolution tale of loyalty and revenge and love. And a glorious Puccini double bill – Il Tabarro, and Suor Angelica.

Of course there was Tramlines, about which I have rambled euphorically already. There was also Songhoy Blues in a Talking Gig, performing (and talking) after a showing of the remarkable documentary They will have to Kill us First, about the repression of music in Mali by Islamist extremists. Malian music is something else I have rambled euphorically about, and Songhoy Blues in particular.

Two gigs in the Crucible Studio, the first under the auspices of Sheffield Jazz – The Kofi Barnes Aggregation, a collaboration between two splendid, but very different, saxophonists. And the Unthanks were as spinetingly and goosebumpy and lump in the throaty as I could have imagined, whilst being, in person, down to earth and funny and delightful.

Of course the year began with, in the space of just a couple of days, hearing the new CD from a musician whose music has been part of my life since I was a teenager, and then learning of his death. David Bowie is far from being the only important musical figure to pass away this year – indeed, that great gig in the sky is looking pretty crowded now, with Prince, Leonard Cohen, Keith Emerson and Greg Lake, Sharon Jones, Mose Allison, Pete Burns, Prince Buster, Gilli Smyth, Alan Vega, Dave Swarbrick and George Martin, to name but a few, rocking up over the course of the year. But Bowie was the one who meant the most to me.

2016 – the year in film

Posted by cathannabel in Film on December 10, 2016

It’s been a funny old year. But focusing for a moment on the year in film, it’s been pretty damn fine. In fact, there’s so much to say that whereas normally I bundle my films of the year review in with telly and music and theatre and general musings on the previous twelve months, I’m doing a stand alone film blog, to match my books of the year extravaganza.

I’m including some things I saw on DVD which may predate 2016 (some which do so by a whole bunch of decades in fact) but I think I’ve broken my personal record in terms of films seen at the actual cinema. Most at Sheffield’s wonderful Showroom, but several at Cineworld’s IMAX for the full 3-D ginormous screen experience.

Whittling this list down to a top ten, even if I don’t attempt to put them in any kind of ranking, is pretty much impossible. However, a top 3 emerges quite clearly, of which more later…

Two of the IMAX films I enjoyed this year were from the Marvelverse. The awesome Captain America: Civil War, which augurs well for the next batch of films from the franchise – action, spectacle, politics and moral quandaries, what more could you ask? Doctor Strange was visually stunning and Cumberbatch was terrific (definitely channelling Sherlock in the early parts of the film), and I look forward to his integration in the Avengers ensemble, riffing off Thor and Cap and co. The third was Fantastic Beasts, from the Rowlingverse, which was fantastic and lovely even if the plot was stretched a little thin to allow us to gasp in wonder at the beasts (reminiscent of the first HP film and the first Star Trek movie, so perhaps this is a feature of being first in a new franchise).

At the Showroom we saw possibly the most French French film imaginable, Things to Come, with Isabelle Huppert. I imagined (but have not attempted) a lethal drinking game, involving taking a swig every time a philosopher is namechecked… It’s a thoughtful film, that eschews comfy answers and pat resolutions, in which in a sense very little happens and there’s lots of talk, but also lots of pensive silences.

Marguerite was, oddly, one of two films based on the life of Florence Foster Jenkins. I haven’t seen the Streep/Grant biopic but this was a lovely and touching fictionalised version, starring Catherine Frot.

I had high hopes of Dheepan, given the director’s track record – he made one of my favourite French films ever, The Beat my Heart Skipped, and A Prophet was also excellent. As was Dheepan, for the first couple of acts. After that it seemed to swerve into, first, a revenge thriller in which previous plot strands were left dangling, and finally into a kind of suburban idyll which surely must have been a fantasy (but why would a Tamil refugee previously living in the banlieue have such a detailed vision of the English suburbs?). Worth re-watching to see if I get a different sense of it, but I ended up baffled.

Anthropoid was a brutal depiction of the assassination of Heydrich and its bloody aftermath. Knowing the outcome increased the tension rather than dissipating it, and aside from a couple of minor Hollywood moments along the way it was gritty and clear sighted in refusing to show the protagonists as unswervingly brave and resolute heroes, but allowing us to see the panic and the doubt.

Childhood of a Leader was another film which seemed to lose its way slightly in the final act. It hadn’t quite earned the coda which was (without giving anything away) several imaginative leaps away from the previous scene – not impossible but a fair old stretch, and I think the whole would have been more persuasive had the finale been played with more subtlety and ambiguity. Having said that, along the way it was excellent, with the building sense of wrongness abetted powerfully by one of the best scores I’ve heard all year, from Scott Walker, no less.

Hunt for the Wilderpeople and Captain Fantastic were, in their different ways, delightful films about family. The former focuses on a ‘looked after child’ who is not only hunted (by the authorities – ‘no child left behind’ is not a slogan you will ever feel the same about after this film) but also hunting, for family, stability, love. It’s very funny, and very touching. Everyone leaving the cinema was smiling. Captain Fantastic was not a superhero movie at all, but the story of a family living off-grid, of a father trying to bring his children up with different values to those of their grandparents and the wider society, but then coming into conflict with those values. It was genuinely thought-provoking, as well as, like the Wilderpeople, funny and moving.

On DVD I saw two cracking Shakespeares. The first was new – Marion Cotillard and Michael Fassbender as the Macbeths. For the life of me I cannot comprehend why the early scene showing them at the burial of a child was controversial – the text is very clear that Lady M has given birth, and equally clear that there’s no offspring around now, so I’d always assumed they had a child that died, even if other productions don’t signpost this. This was possibly the best Macbeth I’ve seen – the two leads were totally compelling and chilling, and there was another terrific score, from Jed Kurzel. Then there was a wolfish Ian McKellen in Richard III, the 1995 film, also featuring Annette Bening, Robert Downey Jr and Dominic West amongst other members of a terrific cast. This is the War of the Roses transposed to the 1930s, with fascism looming and the final battle taking place at a ruined Battersea Power Station rather than Bosworth Field. It takes some liberties with the text, combining a number of characters, for example, but it’s a tremendous production of a play I know well as a text but I think I have only seen on stage once. (That was at Nottingham Playhouse in 1971, with Leonard Rossiter in the lead, and the fact that I can remember the production and especially the final battle scene so vividly after 45 years is a tribute to the performance and the staging.)

The Martian was splendid, I loved Damon’s performance and the scripting of his monologues (the phrase ‘to science the shit out of’ something is one I yearn to use), but also Sean Bean (I had a moment of anxiety that he was going to adopt a transatlantic drawl, but no, he were proper Yorkshire) and Danny Glover. Still out there in the big wide cosmos, Star Trek Beyond was fairly daft but thoroughly enjoyable, and I wish, oh I wish, that I believed we could defeat fascism by playing the Beastie Boys on max volume…

Slow West built slowly and subtly to its bloody conclusion, subverting many of the classic western tropes along the way.

Sing Street was a funny and touching evocation of the early 80s through the classic boy meets girl, wants to impress girl, so forms a band storyline. Quite possibly the storyline behind the majority of bands ever formed. The music is pastiche, but openly and appropriately so, as the motley band of musicians change their style and appearance according to whatever they’ve just heard, or whatever they’ve just been told is cool. Lovely stuff.

I was far from convinced about the worth of a live-action Jungle Book but it was very well done and technically stunning, and the peril seemed more perilous than in the cartoon version. Zootopia was contemporary Disney at its most engaging with a female lead who’s definitely not a princess. She’s a rabbit, but she’s not a princess rabbit, OK? And Finding Dory was as touching and funny as I expected, with the motif of short-term memory loss being particularly poignant as we observe it in a close family member these days. We also liked the otters.

All of which brings me to my top three. I cannot bring myself to rank them, so here they are, in alphabetical order.

Arrival was science fiction at its most philosophical and thoughtful. The theme of language is one that has always fascinated me, and I thought during this of my favourite ever Star Trek Next Gen episode, Darmok, where the crew encounter a people who communicate only through allegory, so their translations are useless because they do not know the stories that are being referred to. ‘Picard and Dathon at El-Adrel’. Amy Adams is magnificent, and the narrative has an emotional heft that I cannot explain without spoilers, only to say that I was still weeping after the credits rolled.*

I, Daniel Blake I have written about elsewhere at length so will not reprise those comments here. It’s not a perfect film, but it’s a tremendously powerful one, and aside from its political importance, the central performances are excellent.

Room is intense. It has to be, claustrophobically intense. In the novel we see everything through the eyes of the child, and of course the film can’t do that. We identify with Ma, who is so beautifully played by Brie Larson, a performance totally without vanity or showing off, where one of the most devastating moments is wordless and it’s hard even to describe how she says as much as she says. Jacob Tremblay is also outstanding and the rapport and intimacy between the two of them carries the film.

A postscript

My three top films have women centre stage. Amy Adams, Brie Larson and Hayley Squires all deliver performances of great subtlety and depth. Squires is second billed but she gets almost as much screen time as Dave Johns and her side of the narrative is vital in showing the full impact of the benefit system. Each of the three is tightly focused on two key characters – Arrival on Adams’ character and Jeremy Renner’s physicist, IDB on Daniel and Katie, and Room on Ma and Jack – and so they only scrape through Bechdel. But Bechdel is not the only way of looking at women on screen and these three win as far as I am concerned by asking complicated, nuanced female characters to carry the story.

*OK, I almost always cry at the movies. Most of those mentioned above triggered a bit of a sob at some stage, but I only mention it when I have been especially overwhelmed.

Books of the Year 2016

Posted by cathannabel in Literature on December 9, 2016

With the luxury of retirement, I’ve done a lot of reading. These days, though, I’m more likely to put a book to one side, temporarily (if I know it’s good but I just can’t quite get into it right now) or permanently, if the writing is clunky and/or clichéd. The pile of ‘to read’ books by my bed seems never to be dented by my voracious reading, and that doesn’t even take account of what’s stored on my Kindle. Life is simply too short to read bad books. Not when there are so many good books waiting to be read – by which I emphatically do not mean just serious, literary books, let alone ‘improving’ books, but books that expand the reader’s sympathies, take them to other places, make them care, compel them to read on and read more.

My policy with this annual blog – eagerly awaited, I know, by my loyal readers – is to make no reference at all to the bad books. I want to recommend, to share my enthusiasms, not to knock anyone’s work.

So these are the books that I loved this year.

In non-fiction two titles on current politics stand out. The first is Jason Burke’s The New Threat from Islamic Militancy. Not an encouraging read, but immensely informative and enlightening, and it seems to me that we need to understand the nature of that new threat, if we are to have a chance of defeating it. The second is Rebecca Solnit’s Hope in Dark Times, recommended to me via the That’s Where the Light Gets In blog, and a real tonic at a time when it almost seems that the battle is not worth joining, that there is nothing we could do in the face of the tide of unreason and prejudice.

I discovered Paddy Ashdown’s WW2 histories, thoroughly researched and thrillingly written. Game of Spies told the extraordinary story of a spy triangle in wartime Bordeaux, involving a secret agent, a right wing Resistance leader, and a Nazi officer, whilst Cruel Victory was a very human story of the Resistance uprising on the Vercors plateau after the D Day landings.

I found myself without any particular plan to do so, reading a succession of accounts of long walks. Really, really long walks. Poet Simon Armitage walked the Pennine Way in reverse, Nicholas Crane undertook a seventeen-month journey along the chain of mountains which stretches across Europe from Cape Finisterre to Istanbul, and Cheryl Strayed walked the eleven-hundred miles of the west coast of America alone. None of them were entirely well prepared or equipped for their journeys, all of them were at times injured, miserable, lost. All three write compellingly and with both poetry and humour about the landscapes and the people they encountered. Much as I loved reading about their journeys, I did not feel moved to emulate any of them.

Another book about wandering came from the Fife Psychogeographical Society, whose blog has delighted me for a long time. From Hill to Sea describes various meanderings around Fife and further afield, with poetry and photographs and even a playlist of the music that accompanied the walks. This wasn’t about walking as a challenge, clocking up the miles or the peaks, but about detours and details, spotting the anomalous, the unexplained.

From the countryside to the city, and Darran Anderson’s Imaginary Cities. This is ‘creative non-fiction’, which draws upon a vast range of texts and cultural artefacts to explore ‘the metropolis and the imagination, … mapping cities of sound, melancholia and the afterlife, where time runs backwards or which float among the clouds.‘ An exhilarating read.

Ian Clayton’s Bringing it all Back Home talks about music the way I think about music. How the music you love becomes woven into your life, your loves and losses, the places you live in, encounter and remember. It’s moving and funny throughout, but the coda will break your heart.

And First Light, an anthology of articles in tribute to Alan Garner, whose books have been part of my life since I first read The Weirdstone of Brisingamen as a child of probably 7 or 8 and it scared the living daylights out of me. Garner’s writing is spare and stark and beautiful. Philip Pullman says of him that he explores ‘the mysterious subterranean links between the present and the past, between psychology and landscape, between the real and the dream. If the rocks, caves, lakes, fens, bogs and dens of the land of Britain had a voice, it would sound like Alan Garner telling a story.’ This collection brings together celebrations of his work from writers/readers including Margaret Atwood, Susan Cooper, Neil Gaiman, David Almond and Helen Dunmore.

In fiction this year I finally got round to some classics that I’d either never read before, or had read so long ago that I could come to them afresh. My reading of Conrad’s The Secret Agent was prompted by the TV adaptation, and of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Sam Baker’s excellent modern take on the narrative. Anne Bronte led me to Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte, a story familiar in broad outline but rich in unexpected detail, even if reading it now one cannot help but be aware of the things that could not then be said.

And two French classics, Les Liaisons dangereuses, and Vercors’ Le Silence du mer.

The former is an 18th century epistolary novel, and an extraordinary one. Where this literary device was usually used to give the sense that one is being admitted to the protagonist’s innermost thoughts, here we find each writer presenting radically different versions of events and motivations depending on who they are writing to. These are highly unreliable narrators, and it is up to the reader to try to tease out the truth, if indeed it is there to be found. Are they immoral, embracing transgression for its own sake, or amoral, indifferent to everything except the games they play?

Le Silence was published clandestinely in 1942, during the Nazi Occupation of France. Jean Bruller’s novel, published under the pseudonym Vercors, is a call to mental resistance to the enemy, written before much organised armed resistance was underway. It describes a household forced to take in a German officer, where the father and daughter maintain silence in the face of the officer’s attempts to communicate with them, and to show them that he is a cultured and civilised man.

In contemporary fiction, I enjoyed new work by writers who feature most years in my ‘best of’ lists.

Stephen King completed his Mr Mercedes trilogy with the excellent End of Watch, and also produced a selection of short stories (as always with King’s collections, they’re of mixed merit, but there are some crackers in there).

Cath Staincliffe’s The Silence between Breaths was one of the tensest narratives I’ve read all year. Read it. Just perhaps don’t read it as I did whilst on a train.

I’d read some of Louise Doughty’s books before (Apple Tree Yard and Whatever You Love) and thoroughly enjoyed them. Fires in the Dark was something else again. The narrative takes us from the late ‘20s in Bohemia to the final days of WW2 in Prague, through the lives of a Romany family. Doughty inducts us into their rich culture as well as drawing compelling and complex characters, so that as the darkness of oppression gathers around them and little by little everything is taken from them, we feel it. Harrowing and very moving, and immensely enriching. Her other Roma novel, Stone Cradle tells the story of a family in Britain, through the changes and challenges of the twentieth century, focusing on the lives of two remarkable women.

I found myself drawn to re-read Chris Mullins’ A Very British Coup, which I knew from the TV adaptation years ago with Ray McAnally. Quite unnerving, sometimes the text could be ripped from today’s papers, but in other respects (the risk of a left-wing Labour leader becoming PM, for example) it seems incredible…

New writers to me –

Deborah Levy’s unsettling Swimming Home

Lynn Alexander’s The Sister, based on the life of diarist Alice, sister of Henry and William James

Walter Kempowski’s account of the chaotic days of the end of WW2, through the eyes of a German family, All for Nothing

Elizabeth Wein’s Codename Verity and Rose Under Fire were powerful and moving YA novels of WW2, with female protagonists, not shrinking from horror but focusing on friendship, courage and love

In Patrick Gale’s wonderful Notes from an Exhibition the notes, part of an imagined posthumous exhibition of an artist’s work, build her story and that of her family, non-sequentially, a bit like a patchwork or kaleidoscope.

Glenn Patterson’s The International is a novel about the Troubles that ends before the Troubles begin, but sets the scene vividly and with black humour

And as always, there’s been a fair amount of murder.

Some old favourites (Rebus, Wallander, Dalziel & Pascoe, Ann Cleeve’s Shetland series), more from some more recent discoveries (Laura Lippman’s Tess Monaghan, Sarah Hilary’s Marnie Rome, and Allan Massie’s Bordeaux novels set in WW2).

I’ll be following up on Jane Casey’s Maeve Kerrigan series, which I discovered after reading her stand-alone novel, The Missing. Another discovery was Michel Bussi, whose Maman a tort was a satisfyingly complex and compelling psychological thriller. And finally, W H Clark’s An End to a Silence was a riveting read, whose sequels I look forward to immensely.

And my novel of the year is Kate Atkinson’s Life after Life. I knew several of her other novels, but this one was just dizzying, overwhelming, enthralling. I read it twice, I had to, and will read it again. Its sequel, A God in Ruins, was a different experience and a troubling one, about which I can say nothing except to urge you to read on because somehow it all comes together in a most remarkable way.

A notable omission. I’m stuck on Proust – about an eighth of the way into the penultimate novel of A la Recherche. So my objective for next year, as well as making at least a dent in the ‘to read’ pile, and discovering lots of wonderful new writers, and re-reading some of my favourites, is to bloody well finish Proust…

Lynne Alexander – The Sister

Darran Anderson – Imaginary Cities

Simon Armitage – Walking Home

Paddy Ashdown – Game of Spies, The Cruel Victory

Kate Atkinson – Life after Life, A God in Ruins

Sam Baker – The Woman Who Ran

Anne Bronte – The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

Jason Burke – The New Threat from Islamic State

Michel Bussi – Maman a tort

Ian Carlton – Bringing it all Back Home

Jane Casey – The Missing, The Burning, The Reckoning

W H Clark – An End to a Silence

Joseph Conrad – The Secret Agent

Nicholas Crane – Clear Water Rising

Louise Doughty – Fires in the Dark, Stone Cradle

Fife Psychogeographical Society – From Hill to Sea

Patrick Gale – Notes from an Exhibition

Elizabeth Gaskell – Life of Charlotte Bronte

Sarah Hilary – Tastes like Fear

Walter Kempowski – All for Nothing

Stephen King – Bazaar of Bad Dreams, End of Watch

Choderlos de Laclos – Les Liaisons dangereuses

Deborah Levy – Swimming Home

Laura Lippman – Hush Hush

Allan Massie – Endgames in Bordeaux

Chris Mullins – A Very British Coup

Glenn Patterson – The International

Rebecca Solnit – Hope in the Dark

Cath Staincliffe – The Silence Between Breaths

Cheryl Strayed – Wild

Vercors – Le Silence de la mer

Erica Wagner (ed.) – First Light

Elizabeth Wein – Codename Verity, Rose Under Fire

Godwin’s law and the Angel of Alternate History

Posted by cathannabel in Politics on November 23, 2016

We’ve all observed Godwin’s law in action. “As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Hitler approaches 1″—that is, if an online discussion (regardless of topic or scope) goes on long enough, sooner or later someone will compare someone or something to Hitler.

We’ve all cringed at the crass hyperbole of comparing some minor injustice – or even some pretty significant injustice – to the Holocaust. We’ve all sighed at the historical ignorance of many of those who make the comparisons, wondering what on earth they do teach them in schools these days.

And of course it’s right that we should check ourselves, as those comparisons spring to mind, to ensure that if we do invoke Hitler, Nazism, the Holocaust, the Warsaw Uprising or whatever it is, we do so mindful of the history, the scale, the world-altering significance and the uniqueness of those events.

But when we hear political rhetoric and recognise its echoes (whether the words are being used consciously or not), when we see tabloid headlines and recognise the way in which they are stoking and inciting hostility and prejudice, when proposals are made (firms having to gather data on ‘foreign’ workers, schools to gather data on the children they teach, registers of Muslims, etc) that remind us of the way in which the ground was prepared for fascism and genocide, of course we have to point this out.

This is not the same as accusing Theresa May, Amber Rudd or Donald Trump of being Nazis, or of harbouring plans for concentration camps. But as we have to keep on pointing out, fascism doesn’t start with that.

It will restore your honour,make you feel proud,protect your house,give you a job,clean up the neighbourhood,remind you of how great you once were,clear out the venal and the corrupt,remove anything you feel is unlike you…It doesn’t walk in saying,“Our programme means militias, mass imprisonments, transportations, war and persecution.”(Michael Rosen)

And it arrives with the drip drip drip of the message about ‘the other’, the other who has the job that should be yours, the place in the housing queue, the easy access to benefits and to everything that you feel you have to struggle for. The other who is not only (somehow) both a scrounger and has nicked your job, but is a terrorist sympathiser, a rapist or a drug dealer. Or, conversely, is covertly running the whole show, the media, the financial institutions and so forth.

You’ve got to be taughtTo hate and fear,You’ve got to be taughtFrom year to year,It’s got to be drummedIn your dear little earYou’ve got to be carefully taught.(South Pacific, ‘You’ve got to be Taught’, Oscar Hammerstein II, 1949)

Hatred isn’t something you’re born with. It gets taught. At school, they said segregation what’s said in the Bible… Genesis 9, Verse 27. At 7 years of age, you get told it enough times, you believe it. You believe the hatred. You live it… you breathe it. You marry it.(Mrs Pell, in Mississippi Burning, dir. Alan Parker, 1988)

We’ve grown used, sadly, to the vilification of migrants and Muslims, the self-evidently false narratives that are promoted on page 1 and whose repudiation (if it comes) is hidden in small type at the bottom of page 2. What’s more recent is the vilification of ‘experts‘ (to use the full designation, ‘so-called experts’). The self-appointed champions of the people, the defenders of the ordinary man or woman on the street, rail against the ‘loaded foreign elite’, ‘out of touch judges’, academics who have no idea of life in the ‘real world’. In reality, of course, these newspapers are owned by members of that very ‘loaded foreign elite’, and are probably rather less in touch with the real world inhabited by most of us as the most rarefied academic or judge.

More alarming still is the growing use of the term ‘enemies of the people’, and the accusations of treachery. The former is a phrase we know from history – the history of Robespierre, Stalin and Pol Pot, under whose leadership it tended to mean at best exile and at worst death. Charges of treachery have also traditionally carried death sentences and as such those accusations feel like incitements to violence – such as the murderous violence meted out to Jo Cox by a far right extremist who gave his name in court when first charged as ‘Death to traitors, freedom for Britain’. This horrifying act, along with the spectacle across the Atlantic of Nazi-style salutes at far right rallies in support of the President-elect, and Ku Klux Klan endorsements of his proposed chief strategist, are warning signs – these views never went away, not altogether, but where they might have hidden in the shadows they are now in the light, unapologetic, emboldened.

What we do and what we say now is vitally important. We cannot let these views become normalised, we cannot just ‘see how it goes’, or assure ourselves and each other that these people don’t really mean it, they won’t go that far, they will settle down, or even that there are sufficient checks and balances in the system to ensure that they cannot carry out the worst that they promise.

In the 1930s there was the real chance of stopping Hitler. Had we known then what we know now, there might have been not only the opportunity but the will. We do know now. We know where that road leads, and we know that there are many points along that road where the progress towards war and genocide can be stopped, but that last time we left it too late. Last time we let it happen. That is, ironically, our best hope now. That there are so many people living who saw the worst happen, who remember what that evil looks, sounds and smells like, and who won’t be so readily reassured that it’s all ok. And those of us who didn’t live through it but who have read and learned and understood enough will be with them.

In 1940 the Jewish writer Walter Benjamin took his own life in the coastal town of Portbou in Catalonia, believing that his chance of obtaining a visa to the USA had gone, and that he faced arrest by the Gestapo. He was mistaken – others in his party received visas the following day and made their way to safety. Who can say what he might have contributed had he been able to hold despair at bay for just a little longer? But this famous passage indicates something of how he saw the world at that time:

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

(Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, and Clarence, the Angel of Alternate History)

Rebecca Solnit suggests a different way of seeing things, inspired by It’s a Wonderful Life.

Director Frank Capra’s move is a model for radical history because Clarence shows the hero what the world would look like if he hadn’t been there, the only sure way to measure the effect of our acts, the one we never get. The angel Clarence’s face is turned toward the futures that never come to pass. …the Angel of Alternate History tells us that our acts count, that we are making history all the time, because of what doesn’t happen as well as what does. Only that angel can see the atrocities not unfolding…. The Angel of History says ‘Terrible’, but this angel says, ‘Could be worse’. They’re both right, but the latter angel gives us grounds to act.

However things turn out, we may never know what difference we made, or might have made. If the threats that we perceive at present come to nothing it will be easy for us and others to say, see, we were over-reacting. If not it will be easy for us and others to say that our words and actions failed to achieve what we hoped. We could just as well say in the first instance that we helped in our small ways, collectively and individually, to defuse that threat, and in the second that things could have been worse.

Because we won’t have Clarence to show us the effect of our acts, all we can do is to do the best we can, to do the right thing, to call out evil when we see it, to draw the historical parallels with rigour and discernment, to speak truth in the face of lies and love in the face of hatred, to stand up for and stand with the people who are threatened by those lies and that hatred.

And in that spirit we think not of the man today imprisoned for life for a vicious murder motivated by hatred, but of the woman he killed, the woman whose life made a difference and will continue to make a difference, who reminded us that we have more in common than that which divides us, and whose family today have spoken out to assert the values that drove her:

We are not here to plead for retribution. We have no interest in the perpetrator. We feel nothing but pity for him, that his life was so devoid of love that his only way of finding meaning was to attack a defenceless woman who represented the best of our country in an act of supreme cowardice. Cowardice that has continued throughout this trial.

When Jo became an MP she committed to using her time well. She decided early on that she would work as if she only had a limited time, and would always do what she thought was right even if it made her unpopular. So she walked her own path, criticised her own party when she felt it was wrong and was willing to work with the other side when they shared a common cause. The causes she took on ranged from Syria to autism, protecting civilians in wars to tackling the loneliness of older people in her constituency.

Jo was a warm, open and supremely empathetic woman. She was powerful, not because of the position she held, but because of the intensity of her passion and her commitment to her values come what may.

The killing of Jo was in my view a political act, an act of terrorism, but in the history of such acts it was perhaps the most incompetent and self-defeating. An act driven by hatred which instead has created an outpouring of love. An act designed to drive communities apart which has instead pulled them together. An act designed to silence a voice which instead has allowed millions of others to hear it.

Jo is no longer with us, but her love, her example and her values live on. For the rest of our lives we will not lament how unlucky we were to have her taken from us, but how unbelievably lucky we were to have her in our lives for so long.

Holding on to Hope in the Dark after Trump

Posted by cathannabel in Politics, USA on November 9, 2016

I am bereft of words. I have not yet read the Rebecca Solnit book, but bought it a couple of days ago on Gerry’s recommendation. I think I will read that now, and take some time out from political analysis of what just happened. Think, understand, mourn – then organise.

So now we know what it felt like to be alive when Hitler came to power. That was my first reaction to hearing of Donald Trump’s devastating victory in the U.S. Presidential election. As Martin Luther King wrote in his letter from his jail cell in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, ‘Never forget that everything Hitler did in Germany was legal.’ Coming after the Brexit vote, Trump’s win induces feelings of total despair.

I am devastated. I no longer recognise my country. How could Trump’s message of hate, misogyny, and racism resonate with so many people? I am baffled, and saddened. I’m afraid for the future of our country, and for the future of my friends. Will my LGBTQ friends still be able to marry the people they love? Will my husband get laid off? Will my Muslim friends get deported? Will the economy collapse? What will happen to the environment?…

View original post 1,510 more words

I, Daniel Blake

Posted by cathannabel in Politics on November 2, 2016

I’m not Daniel Blake. I’ve never been too sick to work, never had to claim Jobseekers Allowance, never had to do battle with the relentless bureaucracy of the welfare system, never been accused of being or assumed to be workshy or a scrounger, never been reduced to zero income, never had a final reminder through the post for a utilities bill, never had to sell my furniture in order to survive, never had to apply for jobs I knew I couldn’t take simply in order to avoid benefit sanctions.

I’m not Katie either. I’ve never had to choose between feeding my children and feeding myself, I’ve never had to think of creative ways of heating my home with bubble wrap insulation and tea lights, I’ve never been driven to shoplift or prostitute myself in order to buy shoes for my kids, I’ve never been evicted or had to live in a homeless shelter or rehoused hundreds of miles from family and friends.

But I can see how it happens. I can see, and apparently those in power cannot, that a benefits sanction can mean that the Katies and Daniels of our land have no money, nothing at all, for weeks on end. They cannot, it seems, imagine that there may be nowhere else to go if your benefits are frozen or delayed, no emergency pot of money, no frivolous spending to be reined in, no family members to help out.

In the aftermath of the 2015 general election (and lord, how long ago that seems now), I wrote this, in relation to the Conservative manifesto pledges on welfare:

Hard work is an excellent thing. But to extrapolate from success and financial security being a reward for hard work, to poverty and failure being a punishment for idleness is unfair. No one achieves success and financial security without an element of luck. No one gets there without state help – for themselves or for their workforce and their business. Luck can suddenly desert any of us, and the line between security and penury is not as clear-cut as we may think. The narrative of homelessness doesn’t start in the gutter, it may start with someone in work, owning their own home, doing OK. Something goes wrong – they lose their job, fall behind on the mortgage and the bills, their family breaks up, their health begins to suffer. And that striver becomes a skiver, dependent on benefits in order to get by, or falling through the gaps altogether into a life on the streets. It’s not impossible, not for any of us.

Toby Young found himself unable to empathise, unable to envisage how ordinary, decent people could find themselves in that nightmare, sceptical precisely because the people portrayed on film are ordinary decent people, and not profligate wastrels, blowing their benefits on dope and flat screen TVs. He acknowledges that he is no expert on the welfare system, but that does not deter him from asserting that Loach has overstated his case, that what is shown as happening to Daniel and Katie wouldn’t really happen.

We’re asked to believe people who claim incapacity benefit are all upstanding citizens who would love nothing more than to earn an honest living if only they were able-bodied.

No, we’re not. We’re asked to believe that the system treats those upstanding citizens who need its help as if they are trying to get something for nothing, as if they are trying to cheat hardworking taxpayers out of their money by skiving when they could perfectly well work. We’re asked to believe not that every person claiming incapacity benefit is a Daniel Blake but that there are Daniel Blakes out there, trapped in the Rules, who have always paid their way, who struggle with the welfare system because they’ve no idea how to play it, and assume that it will be simple and fair.

Young says that

The two protagonists are a far cry from the scroungers on Channel 4’s Benefits Street, who I accept aren’t representative of all welfare recipients. … Katie, too, is a far cry from White Dee, the irresponsible character in Benefits Street.

So having acknowledged that Benefits Street is a highly selective representation of welfare recipients, he goes on to judge the verisimilitude of Loach’s characters by their resemblance to its inhabitants. The location for the programme was James Turner Street in the Winson Green area of Birmingham which Channel 4 describes as “one of Britain’s most benefit-dependent streets”. In other words the street was chosen because it was an extreme, a concentration of benefit-dependency (or, less pejoratively, benefit entitlement).

In contrast the makers of I, Daniel Blake researched many, many cases, talked to many, many people, to inform the narrative and flesh out the two main characters. People like Jack Monroe, who sees herself as ‘the lucky one’ who found a way out of the rabbit hole, albeit not unscathed by those experiences. And the film deliberately avoided some of the more extreme stories of suffering they heard in the course of their research, fearing that they would not be believed. And still the Toby Youngs and Camilla Longs and IDSs of this world complain that it ‘doesn’t ring true’.

I can’t claim first-hand experience of poverty or hunger, although my life has been far closer to Dan or Katie’s than it has to Toby’s or Camilla’s. I have been in debt, I have lain awake worrying about whether the next mortgage payment will take us over our overdraft limit, and I have done the sums to work out how long we could manage on a reduced income before we would have to sell the house. Things worked out, but they might not have done. I could have been Daniel Blake or Katie Morgan, I could still be, if everything goes pear-shaped, and the chances are you could have been, you could still be.

We have to challenge the rhetoric. Those of us who are strivers, hardworking taxpayers, must protest if we’re invoked to support attacks on those who allegedly choose a life on benefits. We don’t have to let them do this in our name.

And we have to protest, loudly and clearly, when the implementation of these welfare cuts makes people suffer, locks them into a miserable existence, a half-life, with no way out. Could they just ‘do the right thing’ and choose to be a striver rather than a skiver? Not if they have to make daily choices between heating and eating. Not if their health precludes most available jobs, not if the job they could get is impossible to reach on public transport, not if childcare is too expensive, not if they don’t have the skills or the qualifications, not if the training places or apprenticeships aren’t available…

If we care at all, if our hearts are not rock hard, if we have any capacity for empathy, if we are human, we cannot be complacent in our status as hardworking taxpayers when people are dying. Read this, and weep. Read this, and get angry.

#WeAreAllDanielBlake

https://cookingonabootstrap.com/2012/07/30/hunger-hurts/

http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/can-no-doubt-benefit-sanctions-9141079

http://realbenefits-street.com/real-experts/

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/oct/26/welfare-sanctions-ken-loach-uk-benefit-system

http://www.ekklesia.co.uk/node/23524

http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/ken-loach-reveals-felt-make-9093260

Aberfan: the sorrow and anger of fifty years

Posted by cathannabel in Events, Politics on October 21, 2016

‘In that silence…’ A powerful and moving commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Aberfan disaster, from That’s How the Light Gets In.

Fifty years ago today, on 21 October 1966, at 9.15 in the morning, the children of Pantglas Junior School had just returned from morning assembly to sit at their desks in their classrooms when spoil tip no. 7 tore down the mountainside, taking just five minutes to smash through houses and the school, burying everything in its path in a sea of thick, black mud. By that evening, as miners from the nearby pits toiled under arc lights, scrabbling with their bare hands at the slurry, the village of Aberfan knew that 187 souls were lost, 116 of them children. A generation had been wiped out.

View original post 3,121 more words

Tears of Rage

Posted by cathannabel in Literature, Music on October 21, 2016

I’ve been listening to a lot of Dylan lately. Early stuff – Witmark demos, basement tapes, that sort of thing. Raw and rough, but with such immense power.

Do his lyrics constitute poetry? I’ve often considered this question, and argued with others about it, not just in relation to Dylan but to other songwriters whose lyrics are held up as shining examples of the art. I don’t think there is any absolute answer.

Many brilliant song lyrics absolutely only work when they are sung. On the page they might seem flat and clumsy, but when you hear them they take wings and fly and soar and take your heart with them. To be a great songwriter does not require one to be a poet – Lennon & McCartney rarely achieve the kind of lyrical brilliance that I would want to defend as poetry; for the most part there are moments, rather than whole songs, as sublime as those moments are. The brilliance of Holland, Dozier & Holland does not lie in their lyrics, and whilst Smokey’s are witty and clever, and less prone to ‘confusion/illusion’, ‘burning/yearning’ cliches, I can think of no individual songs that I would want to present as poems. R Dean Taylor’s wonderful ‘Love Child’ works because of the way the lead vocal and backing vocals are woven together, especially in the coda where Diana Ross’s voice takes the melody with ‘I’ll always love you’, with the urgent rhythms of the backing singers pleading with the lover to wait, and hold on. On the page though, all that is lost.

So do I believe that Dylan is a worthy recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature? Yes, yes I do, despite all of the caveats that so often apply.

Firstly, the lyrics are quite clearly the driving force of his songs. Not accompaniments to the music, nor a vehicle for the voice (indeed the voice divides opinion considerably more than the lyrics), rather the reverse. Secondly, the immense variety of his work deserves recognition. Even just considering his earlier work, which is what I know best, you have the pared down, desperate simplicity of ‘Hollis Brown’, the jaunty viciousness of ‘Don’t Think Twice’, the surreal imagery of ‘Hard Rain’… Thirdly, these are words of visceral power that stay with you and whose portent transcends the time of their writing and the specific concerns that inspired them.

Take ‘Hollis Brown’. The relentless rhythm is matched by the relentless words, the repetition hammering home the hopelessness

You looked for work and money

And you walked a rugged mile

You looked for work and money

And you walked a rugged mile

This kind of repetition is a feature of many folksongs, presumably to help with their transmission in an oral tradition, but here it’s more than that. Hollis Brown walks his rugged mile, walks the floor and wonders why, and his babies’ cries pound on his brain, on and on until he can see no way out other than to spend his last lone dollar on those shotgun shells.

Critic David Horowitz has said of this song:

-

Technically speaking, “Hollis Brown” is a tour de force. For a ballad is normally a form which puts one at a distance from its tale. This ballad, however, is told in the second person, present tense, so that not only is a bond forged immediately between the listener and the figure of the tale, but there is the ironic fact that the only ones who know of Hollis Brown’s plight, the only ones who care, are the hearers who are helpless to help, cut off from him, even as we in a mass society are cut off from each other….

On the same album as Hollis Brown, there’s ‘Only a Pawn in their Game’.

He’s taught in his school

From the start by the rule

That the laws are with him

To protect his white skin

To keep up his hate

So he never thinks straight

‘Bout the shape that he’s in

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their game

The invocation of Medgar Evers’ name and brutal death set up expectations which are undercut at the end of the first verse as Dylan asserts ‘He can’t be blamed’. And the final verse contrasts Evers’ burial, lowered down as a king, with the unanmed assailant’s future death and his epitaph plain, only a pawn in their game. I know I was not the only person who found those words circling in my mind after the murder of Jo Cox, and again after the upsurge in racist harassment and attacks post-referendum.

Then there’s ‘Hattie Carroll’. That killer final verse:

In the courtroom of honor, the judge pounded his gavel

To show that all’s equal and that the courts are on the level

…

And that the ladder of law has no top and no bottom,

Stared at the person who killed for no reason

Who just happened to be feelin’ that way without warning

And he spoke through his cloak, most deep and distinguished,

And handed out strongly, for penalty and repentance,

William Zanzinger with a six month sentence…

Oh, but you who philosophise disgrace and criticise all fears

Bury the rag deep in your face

For now’s the time for your tears

If that weren’t enough the album also includes ‘With God on Our Side’, ‘The Times they are a Changing’, ‘North Country Blues’ – and from the viscerally political to the personal and the melancholy of ‘One Too Many Mornings’.

You’re right from your side

I’m right from mine

We’re both just too many mornings

And a thousand miles behind

which reminds me of Kirsty MacColl’s ‘You and Me Baby’

Except for you and me baby

This is journey’s end

And I try to hang on to all those precious smiles

But I’m tired of walking and it must be miles

That’s just one album, by a man in his early twenties. And this intensely productive period had given us the satire of ‘Talking John Birch Paranoid Blues’, ‘Hard Rain’ and, in real contrast to the melancholy and reflective farewell expressed in ‘One Too Many Mornings’, this:

I aint saying you treated me unkind

You could have done better but I don’t mind

You just kinda wasted my precious time

But don’t think twice, it’s all right

Ouch.

A much less well known song than some of those above, one which I might not have come across had Jimi Hendrix not covered it, is ‘Tears of Rage’.

We carried you in our arms

On Independence Day,

And now you’d throw us all aside

And put us on our way.

Oh what dear daughter ‘neath the sun

Would treat a father so,

To wait upon him hand and foot

And always tell him, ‘No’?

Tears of rage, tears of grief,

Why must I always be the thief?

Come to me now, you know

We’re so alone

And life is brief

Andy Gill, in his 1998 book, Classic Bob Dylan: My Back Pages, suggests a link to King Lear:

Wracked with bitterness and regret, its narrator reflects upon promises broken and truths ignored, on how greed has poisoned the well of best intentions’, and how even daughters can deny their father’s wishes.

and to the Vietnam war:

In its narrowest and most contemporaneous interpretation, the song could be the first to register the pain of betrayal felt by many of America’s Vietnam war veterans. … In a wider interpretation [it] harks back to what anti-war protesters and critics of American materialism in general felt was a more fundamental betrayal of the American Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights.

Sid Griffin in his Million Dollar Bash: Bob Dylan, the Band, and the Basement Tapes, noted the strong Biblical theme running through the song, particularly the ‘life is brief’ motif which links to Psalms and Isaiah, and Greil Marcus wrote that

in Dylan’s singing—an ache from deep in the chest, a voice thick with care in the first recording of the song—the song is from the start a sermon and an elegy, a Kaddish.

So should we worry that this prize is the thin end of the wedge, that, as some BTL commentators have claimed, this means the next Nobel Prize for Literature could go to Lady Gaga or Elton John, or whoever. Seriously? The prize has been awarded “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”. Who could really dispute that Dylan has done that? His influence on other musicians has been extraordinary and creative – Sam Cooke wrote ‘A Change is Gonna Come’ in direct response to hearing ‘Blowing in the Wind’; Jimi Hendrix drew on Dylan’s work to create his innovative take on the blues; John Lennon’s songwriting was challenged by Dylan’s songs to become rougher and edgier and to go beyond the teen romance preoccupations of the Beatles’ early ’60s output; Bowie parodied Bob Dylan’s 1962 homage to Woody Guthrie, “Song to Woody”, addressing Dylan by his ‘real’ name: “Hear this, Robert Zimmerman, I wrote a song for you”.

And undisputed poet Simon Armitage has talked about the impact of Dylan’s songwriting on his poetry:

1984 was also the year I started writing poetry. I wouldn’t claim that there’s any connection, that listening to Dylan made me want to write, or that his songs influenced my writing style. But I do think his lyrics alerted me to the potential of storytelling and black humour as devices for communicating more serious information. And to the idea that without an audience, there is no message, no art. His language also said to me that an individual’s personal vocabulary, or idiolect, is their most precious possession – and a free gift at that. Maybe in Dylan I recognised an attitude as well, not more than a sideways glance, really, or a turn of phrase, that gave me the confidence to begin and has given me the conviction to keep going.

Of course Dylan resisted being ‘the spokesman for a generation’ – who would want that pressure, that endless demand? In the past, too, he’s demurred at being described as a poet, calling himself ‘only a song-and-dance man‘. He’s been said to have chosen his nom de plume in tribute to Dylan Thomas, but has (at least sometimes) denied that. Indeed Dylan has given us many different narratives – that’s how he has defied definition, alternating between telling us stories about himself, often contradicting the previous story he told, and telling us nothing at all.

As is the case right now. From Dylan himself, on the subject of his award, not a word from this man of powerful words. An acknowledgement appeared on his website, and then disappeared again.

So who knows? And who, in any case, would want it to be any different?

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/oct/13/bob-dylan-deserves-to-win-nobel-prize-literature

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/oct/16/women-artists-on-bob-dylan-nobel-prize