Shouting back

Posted by cathannabel in Feminism on September 7, 2013

I’ve been lucky, so far, on the internet. I’ve been the recipient of ridiculous spam, Facebook has insulted me with ads about unsightly belly fat, and I did have one or two spats with a particularly truculent contributor to the comments on the Guardian’s Dr Who blog . But nothing nasty. I use pretty much my real name, and I’ve not consciously steered clear of controversy, but I’m not high profile and I haven’t attracted any vitriol or hate for anything I’ve said. Mostly, I’ve heard from and talked to nice, interesting, funny people, and its been a positive experience. I love the internet, I love the possibilities that blogging, Facebook, Twitter etc offer for communication, for making unexpected connections, for finding stuff out.

But lately some people have had an entirely different experience here. So different that they’ve had to at least temporarily close down and cut off those possibilities, because what they’ve been getting is so unbearably vile, so vicious, so hate-filled. And whilst there have been plenty of people out there to offer solidarity and support, others have been rather quick to suggest that they’ve over-reacted. They’ve mostly avoided the word ‘hysterical’ – always a bit of a give-away – but it’s been there, in the sub-text. How like a woman, to get her knickers in a twist just because someone, or several people, are threatening repeatedly and in very explicit ways to rape and murder her, and sending messages to her parents’ home to show that they do know how to find her if they wanted to carry out those threats. How like a woman, to get upset and angry, and maybe use a bit of bad language when people tell her that her reaction to those threats is all wrong, and all out of proportion.

Some of them are repeating the old advice to not feed the trolls. Now a troll as I’ve understood it, and I have met one or two, is someone who deliberately tries to wind people up, being provocative and inflammatory. They vary from being irritating to being malicious, but by and large, if you ignore them, they go away. Those who have inundated Caroline Criado-Perez and others with threats of horrific, sadistic sexual violence are of a different order. Their message is that women who speak out should shut up, or be made to shut up.

So if we respond by not responding, far from thwarting their mischief-making, we’re doing exactly what they want. We’re shutting up. Retreating.

The recipients of this kind of abuse have no way of knowing whether the threats are real, in the sense that they will be acted on. That uncertainty is part of the intention – to make us think twice about speaking out, to make us look over our shoulders and jump at shadows. To make us afraid.

Those who’ve been in the forefront of the abuse are entitled to take a step back. But their message is clear – we need to shout back, and keep on shouting back. Women, and men who support women, refusing to shut up, refusing to retreat, refusing to make ourselves invisible and inaudible in order to be safe.

So this is me, adding my voice to the shout back.

I’m not on my own.

http://feministfootballfan.wordpress.com/2013/09/06/shouting-back/

http://votevonnywatts.blogspot.co.uk/2013/09/caroline-criado-perez-katie-hopkins.html?m=1

Related articles

- Caroline Criado-Perez says culture must change as rape threats continue (theguardian.com)

- Don’t feed the trolls AKA silence yourself. (thenotsoquietfeminist.wordpress.com)

- Caroline Criado-Perez’s speech on cyber-harassment at the Women’s Aid conference (newstatesman.com)

Furnace Park // an introduction on the cusp of an opening

Posted by cathannabel in The City, Visual Art on August 16, 2013

Reblogged from Occursus – Amanda Crawley Jackson’s account of the Furnace Park project.

In summer 2012, occursus – a loose collective of artists, writers, researchers and students that coalesced around a weekly reading group I had set up with Laurence Piercy from the School of English at the University of Sheffield – organised a series of Sunday-morning walks along unplanned routes in Shalesmoor, Kelham Island and Neepsend. As we looped through the chaotic mix of derelict Victorian works, flat-pack-quick-build apartment blocks, converted factories and student residences, sharing stories and sometimes, quite simply, wondering what on earth we were doing there, without umbrellas, in the rain, we came across the acre and a half of brownfield scrubland we’ve named Furnace Park. In collaboration with Matt Cheeseman (from the University of Sheffield’s School of English), Nathan Adams (a research scientist working in the Hunter Laboratory at the University of Sheffield), Ivan Rabodzeenko and Katja Porohina (founders of SKINN – the Shalesmoor, Kelham Island and Neepsend…

View original post 1,859 more words

In the midst of life, we are in death, etc…

Posted by cathannabel in Literature, Television on August 14, 2013

…. and nowhere more so than in the haunting (in so many ways) French drama The Returned which recently left viewers on tenterhooks (or alternatively furious and vowing never to darken its doors again) with a final episode that left more questions than answers, and a long wait for series 2.

The dead return, apparently unchanged (at least initially), and unaware of their deadness. Camille walks through her front door as if nothing untoward had happened (she’d died in a coach accident a couple of years previously), demanding food and complaining bitterly that her room has been rearranged. There’s no overt horror in her re-appearance, which allows a much more subtle take on its effects upon her family. The pattern is repeated elsewhere as the newly undead attempt to find their old lives and slip back into them, only to be confronted by the fact that other lives have moved on in the meantime.

Where do these revenants fit in, in the literature and mythology of the undead? They are not ghosts, which tend to be seen only fitfully and not by all, and to have no physical substance – Camille and her fellow returners are absolutely here, physically, ravenously hungry and startlingly randy too. Ghosts often have a purpose too – like Banquo they are here to shake their gory locks at those responsible for their untimely demise, or to seek a way of resolving their unfinished business in this world – but if these have a purpose it’s not clear what it might be – at least not yet. They are not zombies, whose physical substance has been reactivated without the personality, the mind, the soul (if you will) that previously accompanied it – an ex-person, reduced to a body and a hunger – these returners know who they were, who they loved, and have the full range of human thought and emotion.

Dramatically, there is much that recalls those stories of individuals believed to be dead, and reappearing unexpectedly to cause consternation and conflict as they try to reclaim their lives (Balzac’s Colonel Chabert, Martin Guerre, Rebecca West‘s Return of the Soldier). However, Rebecca West’s returning soldier and Balzac’s Colonel Chabert are not instantly recognisable as the people they once were. Chabert, who has clawed his way out of a mound of corpses, looks like what his former wife would wish to believe he was, a madman and an imposter. Those who made their way home across Europe, as he did, over a century later, were often changed beyond recognition too, their health (mental and physical) permanently damaged, skeletal and haunted both by what they had witnessed and by their own survival. The return of the deportees was a ‘retour a la vie’, and some at least, with care and medical treatment, did begin again to resemble their previous selves. Like Dickens’ Dr Manette, ‘recalled to life’ after years of incarceration, and gradually establishing a fragile hold on life again.

In The Returned, Camille’s father says to his estranged wife Claire that ‘you prayed for this’ – it’s an accusation rather than a statement, even though in his own way he too had sought a continuing connection with the daughter he’d lost. That reminded me of the episode of Buffy (‘Forever’, Season 5), where Dawn attempts to use witchcraft to bring back her mother, realising as she hears the footsteps approach the door that what has come back will not be the person she is grieving for. She breaks the spell, just in time. This thread is picked up in the following season as Buffy herself crosses back over that threshold between death and life, and feels that she isn’t quite as she was, that she has ‘come back wrong’.

Stephen King explored this too, in Pet Sematary, where the knowledge that one could bring back the deceased is too powerful for the protagonist to resist, even having tested the water, as it were, with a cat (who most decidedly isn’t the creature it was before)

and in the madness of terrible loss and grief does not turn back as Dawn did from bringing back his lost son. The returned in King’s narrative look and sound almost like themselves. Almost. They know stuff though, that they should not know, and they are malign, clearly demonic. Some of The Returned’s revenants seem to know stuff in the same way and to be able to use their knowledge to challenge or goad the living. But whether they are on the side of the angels I would not want to say. Ask me in a year or so, when I’ve seen Season 2.

The Returned‘s revenants were not (despite Claire’s prayers) brought back by the living, they appear to have simply returned. But throughout literature the appearance of the dead amongst the living has always been associated with a threat – with the terror or destruction of the living, or with the exposure of past crimes and injustices. Or, at the very least, the confrontation of the living with the trauma of death, in the person of those who have inhabited the liminal space between death and life. Thus neither the unexpectedly alive nor the undead can simply be reintegrated into society, even if the living can accept them. They haunt us, and are themselves haunted,

What these various narratives address is the sense of unfinished business that is inevitably part of bereavement, and the notion that death is a threshold that might, just, be permeable. There’s a moment in an otherwise entirely negligible children’s film, Caspar the Friendly Ghost (yes, I know, bear with me) where the dead mother entreats her husband and daughter: ‘I know you have been searching for me, but there’s something you must understand. You and Kat loved me so well when I was alive that I have no unfinished business, please don’t let me be yours.’ That one line justifies the existence of the film, for me. Because so many of these narratives are really about how impossible it is for the living to deal with death.

Which takes me back to Buffy, and the extraordinary words that Joss Whedon puts into the mouth of Anya (she’s a thousand-year-old vengeance demon, but don’t worry about that, the point is that she says the stuff that we feel, and think, but don’t say):

I don’t understand how this all happens. How we go through this. I mean, I knew her, and then she’s – There’s just a body, and I don’t understand why she just can’t get back in it and not be dead anymore. It’s stupid. It’s mortal and stupid. And – and Xander’s crying and not talking, and – and I was having fruit punch, and I thought, well, Joyce will never have any more fruit punch ever, and she’ll never have eggs, or yawn or brush her hair, not ever, and no one will explain to me why. (‘The Body’, season 5)

So the unfinished business is not theirs, but ours. And they come back, in dreams, but we know that their presence is not quite right, that time is out of joint if they are here. I’ve dreamed so often that my mother is alive. But never without that sense of unease, which could not be further from the feeling that I associate with her, of warmth and comfort and of being loved. She has gone, and we haven’t got over it, and we won’t, but we know it is real.

Still, that boundary, that threshold, is always disturbingly present, just on the edge of our field of vision, and so we will continue to be fascinated by the notion that sometimes they do come back, and how that might be, even if it is and will always be the stuff of nightmares.

Related articles (beware spoilers)

- The Returned (2004) (rantbit.wordpress.com)

- http://lesrevenants.canalplus.fr/#!/

- some further thoughts on Colonel Chabert here: https://cathannabel.wordpress.com/2013/01/20/sebald-and-balzac-quests-and-connections/

Summer Voyages – La Modification

Posted by cathannabel in Michel Butor on August 2, 2013

http://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2013/aug/01/summer-voyages-la-modification-michel-butor

Great piece about La Modification in the Guardian‘s books blog.

Refugee Week 2013

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 23, 2013

As Refugee Week draws to a close, my thanks go to the bloggers whose posts I’ve republished here – Manchester Archives, Futile Democracy, Cities@Manchester, Bristol Somali Media Group, and to Pauline Levis for sharing her father’s story of the Kindertransport.

I’ve also flagged up campaigns from the UNHCR and Amnesty, and celebrated particularly the work of CARA on their eightieth anniversary.

Thanks too to all of those who have retweeted and shared my posts with their own contacts and reached a wider audience.

Finally, a plug for one of the organisations that work to provide safety in a hostile world, Refugee Action:

and for one particular project close to my heart:

Safety in a Hostile World

Posted by cathannabel in Genocide, Refugees, Second World War on June 23, 2013

English: Für Das Kind Kindertransport Memorial at Liverpool Street Station, London 2003 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the Kindertransport. In November 1938, after Kristallnacht demonstrated clearly to any doubters that Jews in Germany and Austria were in real danger, Parliament agreed to allow unaccompanied children to enter the country, under certain conditions, and with financial support from refugee organisations. An appeal was put out for foster parents here, and in Germany and Austria a network of organisers worked to identify priority cases, and to get the necessary paperwork. The children could bring with them only a small suitcase, in which many parents placed photographs or other keepsakes along with more prosaic items. Between December 1938 and May 1940, 10,000 unaccompanied children, mainly Jewish, arrived in Britain. As the danger spread, Czech and Polish children were helped too. They went by train to the Netherlands, and then crossed the Channel by ferry before taking another train to Liverpool Street station where most were met by their foster families.

The last group of children left Germany on 1 September 1939. A party left Prague on 3 September 1939 but was sent back. The last boat transport left the Netherlands on 14 May 1940, the day the Dutch army surrendered to Germany.

Of the children who joined the transports, some were later reunited with their families, many others discovered after the war that their parents and other close family had been killed. As were many of the children left behind, after the borders closed.

I wanted to tell a Kindertransport story this Refugee Week, and so I asked Pauline Levis about her father’s experiences.

≈≈≈

When 11-year-old Arthur Levi travelled to England with his older sister Inge in 1939, his strongest impressions of the journey were of the warm welcome when they crossed the Dutch border, and the train was boarded by people with flowers and gifts, and of the barrel of biscuits provided on the boat. They were in the unusual situation amongst other children on the Kindertransport, that their father had already arrived here. (He was later interned on the Isle of Man, and then joined the army, where he changed his name from Levi to Levis, for safety should he be captured by the Germans.) Their mother was to follow, six weeks later, the last of the family to make it out of Cologne, and went into domestic service. Both parents lived into their 90s. Members of the wider family were not so fortunate – Arthur’s aunt was deported from France and an uncle from Belgium. His grandfather was long thought to have been killed but it was later discovered that he had in fact died of natural causes in the Jewish old people’s home in Cologne.

Arthur and his sister were fortunate in so many ways. They got out in time. They found a safe place, unlike those who fled to territories later occupied by the Nazis. His immediate family escaped too, and so whilst he lived in a series of hostels for refugee children and foster homes, he did have family, and links with his past, beyond the small collection of photographs he brought with him.

He always felt lucky, and grateful, and his love for his adopted country was such that after six years living in Australia in the 70s, he felt the need to come back where he belonged. When he was given the chance to participate in the Spielberg Foundation’s Visual History Archive, his daughter Pauline had to work to persuade him that his story was worth telling – he was reluctant because he saw that so many others had lost so much more.

Arthur’s family was from Cologne, where they had lived for hundreds of years. His father was a travelling salesman, much of the family had been cattle dealers. Life before the Nazis was not idyllic – his parents’ marriage was turbulent and home life was tense and difficult. Under the Nazis there were some close calls – the Gestapo came for his father just around the time of Kristallnacht, but he’d already left, with the help of his non-Jewish employer. And the old people’s home where his grandfather lived, where many Jewish families had taken refuge in the cellar, was raided, and men and boys over 14 taken away. Arthur had to attend a Jewish school (his own background was secular), where the foreign-born children were targeted first – he remembered the Gestapo arriving, with a list of the Polish children, who were taken away and never seen again. Of Kristallnacht itself he remembered the mix of excitement and fear.

Arthur met Edna Gordon, herself the daughter of Lithuanian Jews who’d come to the UK at the beginning of the twentieth century, when he was 21, and they were very happily married for fifty years. He had a successful career as a dental technician, working for many years in the hospital service.

He died in 2000, on the anniversary of Kristallnacht, 9 November.

The stories Arthur shared with his daughter Pauline shaped her passion for justice, for example in her campaign against the deportation of young Iranian artist Behnam and his family, who were facing imprisonment and torture if they returned, which achieved over 11,0o0 signatures on a petition and ultimately saw the family being granted indefinite leave to remain.

His sister’s son and grandson, along with Pauline, are to take part in commemorations leading up to the 75th anniversary of the Kindertransport later this year. I’m immensely grateful to Pauline for sharing her father’s story.

≈≈≈

Exodus

For all mothers in anguish

Pushing out their babies

In a small basketTo let the river cradle them

And kind hands find

And nurture themProviding safety

In a hostile world:

Our constant gratitude.As in this last century

The crowded trains

Taking us away from homeBecame our baby baskets

Rattling to foreign parts

Our exodus from death.(Kindertransport, Before and After: Elegy and Celebration. Sixty Poems 1980–2007 by Lotte Kramer).

Related articles

- Kindertransport: ‘To my dying day, I will be grateful to this country’ (telegraph.co.uk)

- The unsung British hero with his own Schindler’s List (telegraph.co.uk)

Different Trains

Posted by cathannabel in Genocide, Refugees, Second World War, W G Sebald on June 22, 2013

I’m not a train person in general. Not in the sense that I have any feeling for the ‘romance of steam’ or the beauty of the engines. I’m the wrong gender to feel any urge to catalogue their numbers, or to build model railways in my attic or garden. Trains, like cars, and planes and buses are just ways of getting where you want to go.

In general. But in the context of the stories I’ve been posting and reading and thinking about during Refugee Week, trains have a powerful, poignant, terrible significance. I’ve stolen my title from Steve Reich, whose composition of that name explored the journeys that he had made and that he might have made during the war years, using recorded speech from Holocaust survivors, amongst others.

The railway station is a heterotopic space, holding together both the actual location and the destinations with which it connects. And so Liverpool Street Station for W G Sebald’s Jacques Austerlitz connected him with his own past, as the small boy who had arrived from Prague with the Kindertransport, and with the station on which he’d said goodbye to his mother, clutching a small suitcase and a rucksack with food in it. Indirectly it connected him with the station at which his mother was herded onto a cattle truck and taken off to Terezin.

His name recalls the Gare d’Austerlitz in Paris, where Francois Mauriac describes children being dragged from their mothers and pushed onto the trains, one sombre morning.

Not long after, on another continent, trains crammed with refugees from India to Pakistan, or from Pakistan to India, after Partition, were ambushed and their passengers massacred. The dramatisation of those events in The Jewel in the Crown still haunts me.

Perhaps because on another continent, twenty years later, a train commissioned by an expat who worked for the Nigerian railways to take Igbo refugees south, was ambushed, and its passengers massacred. Among them were the people who my father had found hiding in an abandoned house opposite our own, in Zaria, and taken to the army compound in the back of his car, covered with blankets, hoping they would find safety. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, in her wonderful novel Half of a Yellow Sun, describes the arrival of another train full of refugees that did reach safety, but traumatised, mentally and physically.

I think sometimes of a children’s book by Susan Cooper, who can conjure up a terrifying sense of evil, enough to chill adult bones – it’s part of her The Dark is Rising series, but I can’t recall which – in which the rhythms of the train say ‘into the dark, into the dark, into the dark…’ Hard to get that out of one’s head, once it’s been introduced. And I think of it every time I read the accounts of those trains crossing Europe, heading East, to ‘work camps’, to Pitchipoi, into the dark.

And perhaps most hauntingly, of ‘le train fantome’. In the summer of 1944, as the Allies were advancing across Europe, with Paris liberated, the convoys were still rolling.

But not all of the trains took their passengers into the dark.

This photograph captures an extraordinary moment. The 743rd tank battalion encountered a group of civilians, skeletally thin, terrified. They had been en route to another camp, but abandoned by their SS guards – at this moment they understood that they were free.

And at railway stations in England, in 1939, and so many years since, the trains have brought people into hope and life and freedom. They brought with them not just the belongings that they had managed to salvage and to hold on to on the journey but the places they had lived, and the lives they had to abandon, and the memories that would shape them.

For how hard it is

to understand the landscape

as you pass in a train

from here to there

and mutely it

watches you vanish

(W G Sebald, Poemtrees, in Across the Land and the Water)

Related articles

- The Haunting Persistence of Memory: W.G. Sebald’s “Austerlitz” (rosslangager.com)

- Disused train station to host Holocaust museum (praguepost.com)

- http://d-sites.net/english/reichtrains.htm

- http://underagreysky.com/2012/10/01/platform-17-at-the-grunewald-station-berlin/

- http://www.lesdeportesdutrainfantome.org/index.htm

- http://www.filmsdocumentaires.com/portail/odyssee_train_fantome.html

Oxfam and World Refugee Year, 1959-60

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 22, 2013

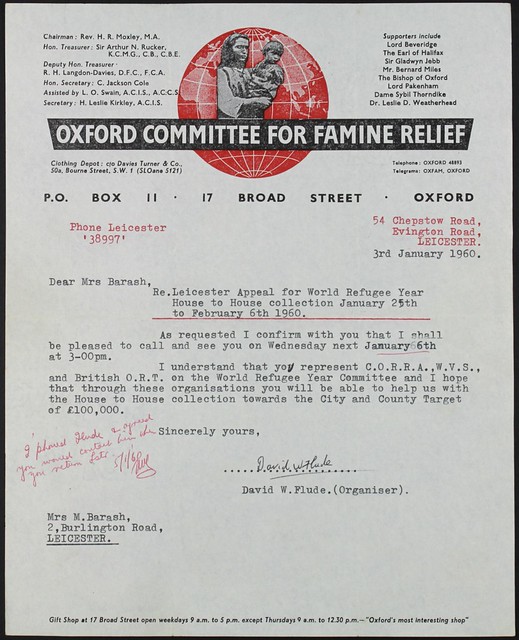

The Oxford Committee for Famine Relief was founded in 1942 by a group of Quakers, social activists and Oxford academics to campaign for food supplies to be sent through an allied naval blockade of occupied Greece during World War 2. In 1965 they became OXFAM adopting their new name from their telegraph address.

They already had a gift shop in Oxford when this letter was written in January 1960, ‘Oxford’s most interesting shop’. I wonder what it sold.

Mrs Barash was very involved in the support of refugees in Manchester during and after World War 2. Her contribution is recorded in material held in the archives at the Greater Manchester County Record Office .

World Refugee Year was a United Nations led initiative and ran from June 1959 until May 1960. By July 1961 £9 million had been raised and the final total was even higher. It inspired a new…

View original post 21 more words

When you don’t exist

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 21, 2013

Amnesty International ‘s current campaign for protection and fair treatment of refugees and asylum seekers.

To flee Syria: From hell to hell.

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 21, 2013

A powerful post from blogger Futile Democracy on Syrian women refugees.

The Syrian crisis poses an intense amount of questions for lawmakers across the Globe, with each question just as important and as crucial to the process of peace than every other. Do we arm the rebels? If not, then what next? If we are to provide arms to the rebel groups, which rebel groups to provide arms to? How to know and ensure those arms won’t fall into Islamist hands? How to ensure a peaceful and stable democracy upon the fall of Assad? What balance to strike with regard diplomacy with the Russians? How to deal with unwanted intrusions of Iran? These are all grand scale, legitimate questions that rightly require thoughtful and decisive action from the international community. There is however, one major and shocking crisis that we seem to hear very little about, and that is the refugee crisis. And within that crises, is the crisis of the…

View original post 1,873 more words