Archive for category Personal

Love is in the noticing – thoughts on 2025

Posted by cathannabel in Personal on December 31, 2025

This is a purely personal take on 2025. I cannot bear to bring to mind, let alone attempt to write about, what this year has been in terms of world events and politics at home. This is cowardly, I know, but there are better minds than mine grappling with the state of things, and all I could do would be to repeat uselessly how absolutely bloody awful everything is, and how hard it is to see any glimpses of hope, as the handcart in which we are going to hell appears to gather speed. So, I will talk about my little world instead.

2025 – the year when my father’s hold on life finally slipped, after 97 years and the erosion of his mind and memory by dementia. I reflected on his life here. Writing about him, on this site and on the Guardian’s Other Lives obituary section, was my way of honouring who he was, before.

And it was a year when we celebrated love, companionship and family as my daughter married her partner of ten years – a purely joyful day, as the sincerity and seriousness of their commitment was expressed joyfully, as everyone there shared in their joy. Of course we were conscious of the people who should have been there but, as Tracy Thorn puts it in her song ‘Joy’, ‘because of the dark, we see the beauty in the spark’. It was a deeper thing than just happiness or contentment, and that’s because we were aware, we could not be unaware, of mortality and of the fragility of life but at the same time, daring to rejoice in the couple’s commitment to their shared future.

A year when I decided to take my health seriously, something I just couldn’t put my mind to for a while after M died. It had to be sustainable change, anything else is simply demoralising. I changed my diet (I didn’t ‘go on a diet’, I’ve been there, done that, and it is always miserable and always short-lived), and I stopped drinking alone (I’d been kidding myself it was making evenings on my own feel better, but it really wasn’t, and in the early hours of the morning, it felt a lot worse). And having discovered that Pilates is a form of physical exercise that I actually enjoy (who knew there was such a thing?) I added two live on-line classes to my weekly studio class, and found myself really making progress. Now, I didn’t do any of this with the intention of losing weight, which is a good thing, because I have lost not one ounce or one inch. But because I had other goals than that, I can be philosophical about the weight thing, rather than seeing it as a failure. I’m healthier, physically and mentally, and that’s enough. (By the way, if you feel moved after reading this to send me links to miraculous weight-loss techniques, please note that they will be deleted unread and you will be blocked. Cheers!)

Late last year I took on the role of Chair of the Under the Stars Board of Trustees. One of my best decisions ever was to join them as a trustee in 2023, and to be part of the incredible work they do. I feel privileged to be able to support the staff and the CEO in particular, and to see our participants finding joy in performing on the Crucible stage, at the Tramlines festival, and a variety of other venues. Stephen Unwin’s book Beautiful Lives, which traces the history of attitudes to people with learning disabilities and looks at how we can do better, was my non-fiction read of the year (see my books blog). It’s heartbreaking and horrifying – not just the murder of ‘useless mouths’ during the Nazi era but the denial of agency and dignity for so long to so many. But it’s also hopeful, and personal, and it moved me a great deal. This year I was cheering on Ellie Goldstein, who has Down’s Syndrome, as a competitor on Strictly Come Dancing. She gave the lie to any idea that ‘learning disability’ means inability to learn, as she grasped complex sequences of tricky dance moves that I would never be able to hold on to – whenever I was at a disco in my younger years I used to head for the loo or the bar when some kind of Macarena/Timewarpy thing got going (I can just about do the Conga). And this year Nnena Kalu, an artist with learning disabilities, was awarded the Turner Prize. If we stop putting all those with LD in a box together, and start listening to them as individuals, finding out what they can do, what they love doing, what hurts them and what gives them confidence, they will achieve more, and they will have a shot at finding joy. I’ve seen it, and I’ve found joy in it myself.

One of my big projects for 2025 has not yet come to fruition – finding a publisher for The Thesis. But I have a better sense of how it needs to be revised and reshaped to make that more likely and, too, a better sense of how much I can realistically do/am willing to do. It’s easier to do that kind of work when you’re within the context of a University, with full access to physical and electronic resources and to people who know stuff. But it’s not just that – I’m older than when I did the PhD, and I’m on my own now, and I don’t have the energy I had ten years ago. So I’m going to update the thesis, taking account of material published since I submitted it, and adapt it to address a wider readership rather than an external examiner. I want it to intrigue and interest readers rather than to prove myself as a scholar. I think that’s feasible, and so I’m not giving up on my dream of seeing the piece of work that absorbed and fascinated me for so long as a published book.

It’s now over four years since M died. The process continues. I’ve adapted lots of my domestic routines of course, and changed a lot of things around the house to make it fit me better. I’ve taken big decisions where I had to (the knee replacement surgery, getting rid of the car), and squillions of smaller decisions as I re-evaluate what I do and how I do it. My big decision for 2026 (so far) is that I will be going on an ‘escorted tour’ taking in Helsinki, Tallinn and Riga, three cities I have never visited and know only a little about. It may turn out that it’s not the sort of holiday that works for me, but if it is, it opens up so many possible ways of travelling and seeing new places. It’s a bit scary – I’m an introvert, and am fairly crap at small talk, and the trip will inevitably involve talking to strangers – but going on an organised tour makes some things a lot easier to contemplate as a solo traveller (see my blog about my previous city break with my son for all the reasons why it might make me rather anxious).

I suppose at some point ‘widow’ will cease to be a defining word for me, but at this stage in the process, it still feels deeply significant. I am still conscious all the time of his absence and it still feels strange – only recently I’ve had the sensation sometimes when I half-wake in the night that I’m not on my own and then the realisation that of course I am. I don’t mean I sense his presence, just that, whilst I’m fully awake I am used to the strangeness of solitude, but in those drowsy moments it puzzles me. I talk about him a lot, to family and friends who knew him, and to people who never knew him, because I can’t talk about my life without talking about him. I switch between ‘I’ and ‘we’ constantly and probably not consistently, because my adult life comprises a ‘before’ and an ‘after’. It’s not that ‘I’ was subsumed in ‘we’, just that our lives were so tangled up together ‘before’.

The title for this post is a quote from the Pixar film Soul, which I used in my speech at my daughter’s wedding last August:

“Life isn’t about one big moment. It’s the little things: walking with someone you love, sharing a laugh, watching the light hit their face just right. Love is in the noticing. The ordinary days that turn out to be everything. And maybe the whole point isn’t to chase the grand purpose, but to love deeply, and really live, right where you are.”

I don’t know whether the writers of Soul were consciously echoing Thornton Wilder’s play Our Town, but it’s not too much of a stretch to think that they were, given how popular the play is in the US. I recently read Ann Patchett’s stunning novel, Tom Lake, in which the play is the thread that runs through the narrative, and was so struck by it that I sought out and watched on YouTube the televised stage version with Paul Newman. And this, in the final act, jumped out at me:

EMILY: ‘Live people don’t understand, do they?’

MRS GIBBS: No dear – not every much.

EMILY: They’re sort of shut up in little boxes, aren’t they? … I didn’t realise. So all that was going on and we never noticed. … Oh, earth, you’re too wonderful for anybody to realise you. Do any human beings ever realise life while they live it? – every, every minute?

STAGE MANAGER: No. [Pause] The saints and poets, maybe – they do some.

Maybe that’s right, we can’t realise or notice every minute, we’re too busy living them, but we can try – to notice and to treasure. There are two strands of thought here for me. One is that the ordinary days ‘turn out to be everything’, a theme that I explored in my eulogy for M, focusing on the day before he died, about which I would remember hardly anything except that it was the last ordinary day, and thus extraordinary. The other is that joy is something we hope for rather than being able to predict or plan for, but that finding it depends on us noticing, noticing the people who we love and who love us, the beauty in music, in words, in the landscape or skyscape. And it depends on us realising that there’s a kind of defiance in joy, that it faces down the dark, the loss and grief, not denying them but just saying ‘there is also this, and this is marvellous and wonderful’, throwing the joy in those marvellous ordinary days in the face of whatever the year might bring.

I look back at 2025 with gratitude to all the people who made it good. Wonderful family and friends, sharing each other’s joys and sorrows. The care home staff who looked after Dad, treated him always with affection and respect, and held his hand as he slipped away. The Under the Stars team and our participants. The musicians who stirred my soul, my mind and my feet. The writers whose words allowed me to cross continents and centuries and to see into other people’s hearts and minds.

So as we move from one year into another, let’s ‘gather up our fears/And face down all the coming years’. Let’s hang on to our hats, hang on to our hope, let’s keep on keeping on. See you on the other side…

Tracy Thorn, ‘Joy’, from Tinsel & Lights, 2012

When someone very dear

Calls you with the words “everything’s all clear “

That’s what you want to hear

But you know it might be different in the New Year

That’s why, that’s why we hang the lights so high

Joy, Joy, Joy, Joy,

You loved it as a kid, and now you need it more than you ever did

It’s because of the dark; we see the beauty in the spark

That’s why, that’s why the carols make you cry

Joy, Joy, Joy, Joy Joy, Joy, Joy, Joy

Tinsel on the tree, yes I see

The holly on the door, like before

The candles in the gloom, light the room

the Sally Army band, yes I understand

So light the winds of fire,

and watch as the flames grow higher

we’ll gather up our fears

And face down all the coming years

All that they destroy

And in their face we throw our

Joy, Joy, Joy, Joy

It’s why, we hang the lights so high

And gaze at the glow of silver birches in the snow

Because of the dark, we see the beauty in the spark

We must be alright, if we could make up Christmas night.

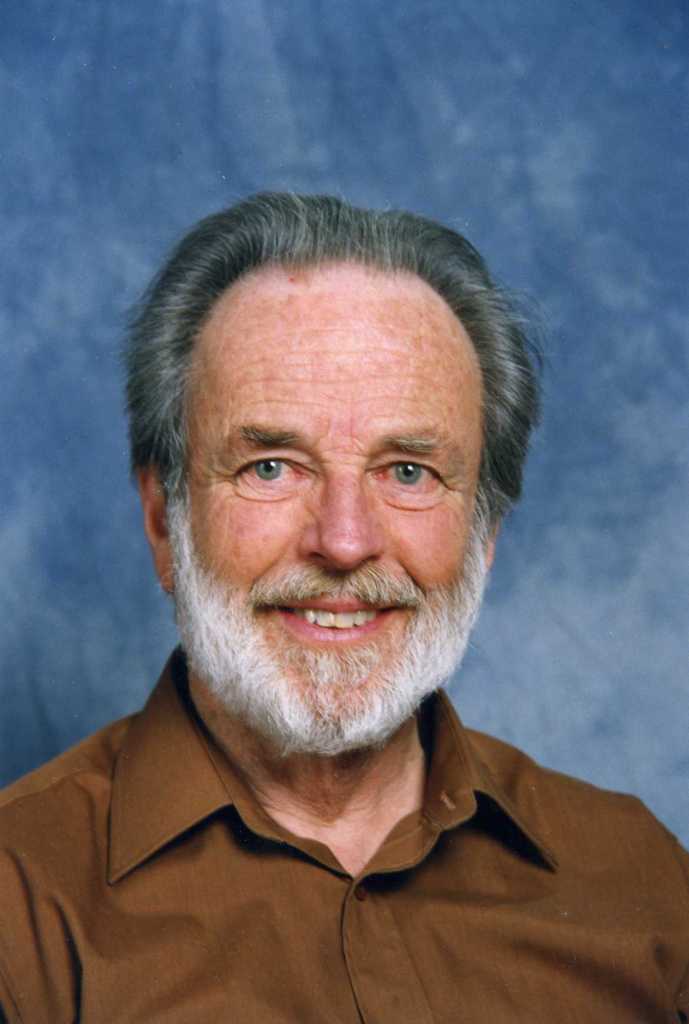

Dad

Posted by cathannabel in Personal on June 16, 2025

John Hallett, 26 December 1927 – 30 March 2025

Trying to sum up anyone’s 97 years of life in a not unreadably long blog post is a challenge. In the case of my Dad, John Hallett, who died on 30 March, it’s impossible. As a friend put it, at the celebration we held for his life, he packed at least two lifetimes into those 97 years. And each time I talk or write about him, someone reminds me of some other project, activity or passion that I’d forgotten, or never even known about. He set the bar very high for us all – whatever I’ve achieved in my life seems small beer in comparison – and he wasn’t always very good at telling us how proud he was of us (this was a generational thing, and certainly learned from his parents), though we know he said it to others. My niece had the poignant experience of hearing her grandad, who no longer recognised her, telling her about his lovely granddaughter and great-grandson and how proud he was of them. Most importantly, we knew, always, that we were loved, and that our parents’ love was not conditional upon us achieving things, and that gave us the freedom to be who we wanted to be, who we were meant to be.

John’s early life was pretty conventional – his father was a civil servant who’d fought in the first war, and was an active member of the Home Guard in the second. They lived in Thornton Heath, where Dad was born in 1927, and then moved to North Harrow with his two younger siblings. As a young teenager during the War, he enjoyed the excitement of spotting aircraft and watching the searchlights to cheer as German planes were shot down, until one of his schoolfriends was killed along with their family during the Blitz – a sobering experience. This did not, however, dampen his enthusiasm for aircraft, and the first stage of his career was in aircraft design.

John took up an apprenticeship at de Havillands, leaving school against the wishes of his father, who had wanted his eldest son to follow him into a stable career in the civil service, and he stayed there for four years after the apprenticeship, working in the Design Office.

He left de Havillands because, as a Christian pacifist, he could not countenance working on military projects, and he had begun to think of a future as a teacher, inspired by people he knew and admired. He trained at Westminster College, and then took up his first teaching post at Chatham Technical College (teaching technical drawing, maths, and RE). By then he was married to Cecily, who was to be his strength and his stay until her death in 1995. They’d known each other for a long time, through church, but only gradually came to realise that their friendship was blossoming into love. They lived at 24 Blaker Avenue, in Rochester, Kent. I was born in a Chatham hospital in 1957, Aidan and Claire were born at home in 1958 and 1960 respectively.

The faith that he and Cecily shared was fundamental to their lives, and whilst I do not share their faith, I do share so many of their values, their political beliefs and their approach to what is important about life. They were pacifists, members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation. They were passionately anti-apartheid (many of their ‘expatriate’ colleagues in West Africa at least considered moving on to South Africa or Rhodesia when Nigeria imploded into civil war, but that idea was anathema to them). I learned from a very early age about the slave trade, visiting forts along the Ghanaian coast where slaves had been held before being transported across the Atlantic, and was aware of civil rights struggles in the US and anti-apartheid activism in South Africa and Rhodesia – political issues of the day were a staple of discussion around the dining table each evening. They were socialists, staunch Labour voters. And they were concerned about the environment long before it was the norm.

They both became interested in the idea of working in West Africa, in one of the newly independent nations, but realised that John would need a University degree to teach there. So he did A levels at a local technical college and then enrolled at City University in London, on a scheme designed for those who had been unable to study to degree level during the war years, and obtained a First in Physics and Maths. John was studying part-time alongside his teaching post, whilst Cecily managed the home in Rochester, and brought up the children. John’s father Dennis, a deeply conservative man, never came to terms with the plan to work in West Africa (or ‘darkest Africa’, as he consistently called it), and when we returned home on leave, John had to wait until his father had left the room before talking to his mother about our experiences there.

The family flew out to Ghana in 1960 (with three children, of whom I am the eldest, then aged 3), and a new home on Asuogya Road, on the campus of Kwame Nkrumah University of Science & Technology in Kumasi. Their fourth child, Greg, was born in Kumasi in 1962. John hadn’t had a conventional route to University teaching, and used to comment that he’d arrived as a lecturer having never attended University before – he also often felt that he was only one lecture ahead of his students.

Both John and Cecily became involved in the life of the University, particularly in chamber music concerts. Cecily was an accomplished pianist, and Arthur Humphrey, a colleague, friend and honorary grandparent, played the spinet and recorders. They also held more informal musical evenings, which John’s colleagues and students from the University regularly attended. John preached regularly (both he and Cecily were Methodist lay preachers) at small village churches outside Kumasi, one of which presented (and robed) him in a splendid kente cloth on his last visit. We still have the cloth, somewhat faded and a little damaged after all these years, but still a beautiful reminder of the life we had in Ghana.

He taught Physics and Maths at KNUST but became increasingly interested in pedagogy, rather than in the research aspect of his subjects (despite pressure from his Head of Department – he resisted the idea of, as he put it, knowing more and more about less and less), and was an examiner for the West African Exam Council, and Chief Examiner for O level (the latter involved him designing practical tests which could be carried out in any school, and visiting schools to assess whether they had the necessary apparatus). He was involved with the Ghana Association of Science Teachers, and wrote a Physics O level textbook tailored to the resources available in West African schools and to the experiences of the students, which remained in print for many years.

This growing interest in education per se led him to take up a post at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Northern Nigeria and the family moved there in January 1966. I don’t recall the first part of our journey (by sea from Tema to Lagos) but vividly remember the 600 mile train ride from Lagos to Zaria. The timing of our move turned out to be most inauspicious, as a series of coups and counter-coups rocked the region, and massacres of Igbo people took place in May and September of that year in the area where we lived. We were not in danger at this stage – the violence was very precisely targeted at Igbo people – but of course it was traumatic for the adults to witness what was happening, often to people they knew, and they kept as much of this from us as possible.

The only incident that I recall was when a group of men approached our house, and Cecily and a neighbour took all of the children upstairs and put a record of children’s songs on, whilst John and the neighbour’s husband went outside to speak to them. Strangely, in my memory the men were carrying sticks, but in reality, as I discovered much later, they had machetes. They turned away from our house, but went on to kill a number of people nearby.

I remember being aware of conversations between the adults that stopped abruptly when they realised I was within earshot, but it was not until my teenage years when I pieced together the fragments to understand what had been happening, and this was formative. There is one particularly powerful story that I discovered from talking to my parents and visitors who had been in Nigeria with us. Opposite our house was an unoccupied bungalow, in which we used to play sometimes. I recall being forbidden to do so – snakes were mentioned and I needed no other deterrent. In reality, John had discovered a couple of young Igbo men hiding there. He got them into the family car, covered in blankets, and drove them to the army base, where it was hoped they would be safe. Meanwhile a friend who worked for the railways commandeered a train to take Igbo refugees south to safety, and these two young men joined that group. Tragically, the train was deliberately derailed, and they and others who were fleeing the pogroms were murdered. On both of these occasions, John felt that he had to at least try to intervene. I have often wondered how he felt as he approached the armed men outside our house, and how Cecily felt, knowing what he was doing. And how he felt as he drove those young men to what he hoped might be sanctuary, knowing that if the car was stopped and searched, they would be killed, and he might be in danger too. I don’t know, because he never spoke of these events in personal terms. I believe he felt that he had no choice but to act as he did, whatever the risk.

As I learned about these events, which had happened around me, without my knowledge or understanding, I found I needed to understand the wider issues, and this lead me to read widely about Partition, the Holocaust and the Rwandan genocide.

The family returned home on leave in the summer of 1967, but the worsening situation meant that Cecily and the children could not return, and John travelled back to Zaria alone, to complete his contract, returning to the UK in Easter 1968. We did visit him at Christmas, a rather nervy visit given the volatility of the situation and the presence of armed (but barely trained) soldiers around the city.

Someone once asked me if I blamed my parents for taking us to West Africa, a question that utterly baffled me. On the contrary, I’m in awe of their courage in taking that step, and very grateful for it too. We gained so much – on our return to the UK our horizons were so much wider than those of our contemporaries, and whilst that meant we had a lot of catching up to do on popular culture and so on, it gave us a different perspective, and I think a more generous one. Certainly those years – and the culture of talking about politics and ethics and religion in our home – informed each of us in our developing views about all of those things as we grew older. We would not be the people we are, had our childhood been spent in England.

Cecily and the children were living in the family house in Rochester, and places were found for us at the local primary schools, but on John’s return he took up a post in the Education department at Trent Polytechnic, where he would remain until his retirement. He and I found a temporary home with one of his old friends (a fellow member of the ‘Brew Club’ at Westminster College), so that he could start at Trent, and I could start at Queen Elizabeth’s Girls’ Grammar School in Mansfield. The rest of the family moved up to Nottinghamshire once our new home in Ravenshead was completed.

Whilst at Trent, John was involved in innovative initiatives such as the generalist Education degree and the Anglesey project, worked with VSO to train volunteers for their overseas service, and also took up every opportunity to travel with the British Council or under the auspices of the Polytechnic to visit schools and educational projects in Nepal, Kenya, and the USA. In addition, John was very concerned with the environment, and published, with Brian Harvey, an economist, a well-received textbook on Environment and Society in 1977.

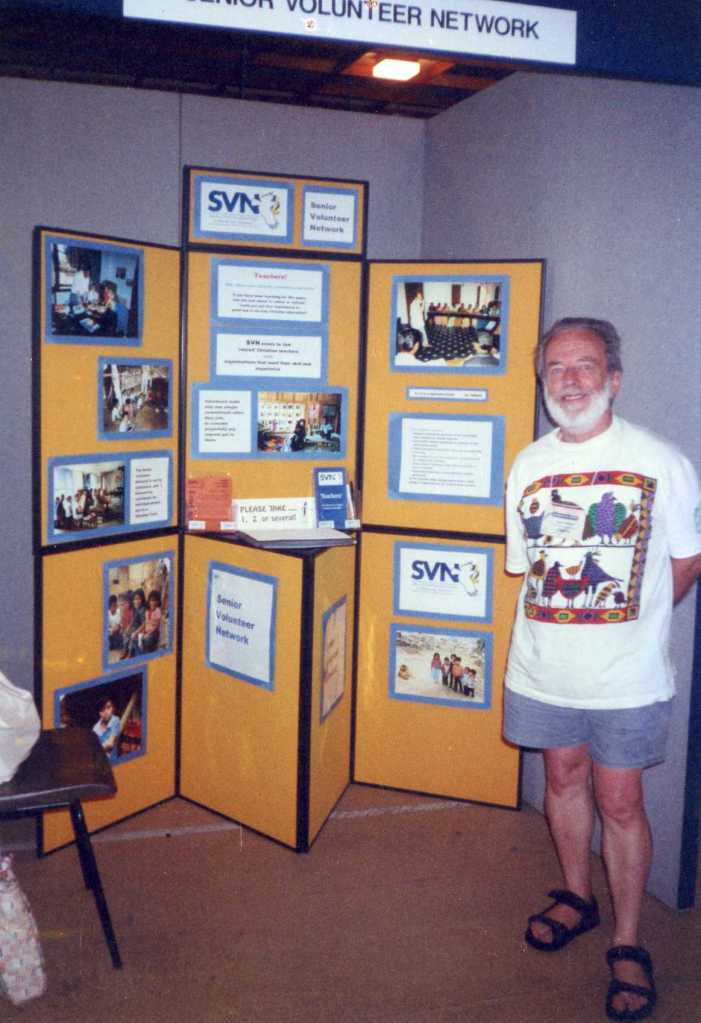

He retired (by then he was Head of the Education Department) in 1987, aged 60, but rather than leading a quieter life, he had a vision for a charity, Senior Volunteer Network, which would put retired teachers/head teachers and other education specialists into projects worldwide, and began to turn this into a reality.

He and Cecily made the most of the freedoms of his retirement (she had retired from primary school teaching some years previously). They both became involved in leadership of the Ravenshead Christian fellowship, which later became Ashwood Church (now based in Kirkby in Ashfield). In the early days of the Fellowship, we met in members’ homes or in the Village Hall. John and Cecily held open house on Sunday afternoons for young people in the village (50 years on, people still talk about how the house was full, every seat taken, and every window ledge and the stairs too) – their home in Ravenshead was called Akwaaba, which in the Twi language spoken in the part of Ghana where we had lived, means ‘welcome’. Part of our parents’ joint legacy to us is the idea of family as an open, welcoming place that embraces new members, whether related by blood, law or none of the above. In West Africa we were a long way from our aunts, uncles and grandparents, and so we accumulated a number of aunts and uncles, friends of my parents who visited regularly, and who I still think of as ‘Aunty Betty’ (with whom I still exchange Christmas cards), ‘Uncle Arthur’, or ‘Uncle Rex’. And in Ravenshead that took the form of opening our doors to random teenagers, some of whom became part of the church (and still are), others who never did, but had reason to be grateful for our parents’ warmth and support, as well as for the Sunday afternoon tea.

As keen walkers, John and Cecily led youth hostelling expeditions to the Lake District, one of which memorably involved Cecily’s group of walkers requiring the Mountain Rescue Service, after getting lost on Great Gable in driving rain and mist. John’s group had taken what was expected to be the more challenging route, only to find when they got to the hostel that we had not yet arrived. They called at the Mountain Rescue centre, at roughly the time that two of Cecily’s party arrived, having been sent out as envoys whilst we huddled behind a rock for (minimal) shelter, and gave their account to the team, enabling them to find their way straight to us.

John was a governor at a number of local schools, volunteered with Mansfield Samaritans (Cecily was a founder member of this branch), and was involved in local politics. He ran regularly, and completed the London Marathon, aged 63, in 1990 – he’d been a keen runner as a young man (plenty of stamina, less speed, due to his short stature), which had taken its toll on his knees and he had to have two knee replacements later in life. He undertook many walks with Cecily (and their dog, Corrie) after his retirement, including the Coast to Coast Walk, and along the Northumbrian coast. Having visited Nepal during his work with Trent Polytechnic, he returned to Everest to climb as far as the snow line, fulfilling his dream to stand on its slopes.

In 1995 Cecily died of pancreatic cancer, aged 65, only a matter of weeks after the diagnosis. It was a huge shock, and an incalculable loss to John and to the family – and to so many more people, as we all discovered from the messages that flooded in after her death. She saw herself as an accompanist – in musical terms this means that she wasn’t there to do the virtuoso solo stuff, but to enhance the performance of other musicians – but she did far more than that, and could have done so much more (at the time of her death she was gaining qualifications in counselling, and working with a Nottingham homeless charity). At the events celebrating Dad’s life, so many people talked not just about John but about ‘John and Cec’. They had different, and complementary strengths, they were a partnership in every sense, and their legacy is a shared one, for us and for the many other people with whom they worked and worshipped.

When Cecily died, SVN was still an idea rather than a reality, and in the aftermath he threw himself into setting up and leading the network, sending volunteers around the world, and travelling himself until his eyesight began to fail due to macular degeneration. SVN still thrives, and the family still has links with it, through Claire who is now a trustee.

John remained active until his 90s, undertaking a skydive to celebrate his 90th birthday, but his sight loss was by then significantly restricting his activities as he could no longer drive, or use the computer. The pandemic shrank his horizons significantly, particularly since he could not easily compensate for the loss of face-to-face social activity with on-line due to his deteriorating sight. In 2020, just before the first lockdown, his youngest son Greg died of bowel cancer, a desperately heavy blow. The death of my husband Martyn in 2021 was also a major shock to him. In 2022 he was formally diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and the decline from that point on was fairly rapid. He was cared for at home by Claire until he needed residential care, and moved into Lound Hall Care Home, near Retford, in 2023.

During those last years, as the fog engulfed him and he became more dependent on others, it was sometimes hard to remember the man he had been. He was a man of bold decisions – leaving school to work at de Havillands, against his father’s wishes, leaving de Havillands on a matter of principle, training as a teacher and undertaking a part-time degree whilst working, taking his young family to West Africa (again, a decision of which his father profoundly disapproved), and then changing direction again to focus on education, and finally setting up SVN in his retirement and travelling to often remote and dangerous places to work on educational projects. He was a leader, from his days as a Cub and Scout where he progressed from ‘Sixer’ to Assistant Scout Master, to his final post as Head of the Education Department at Trent and his role in the church. We all remember family walking holidays when Dad would lead the way so confidently that we all had to rush to keep up, as he was the one with the maps and the refreshments… At the care home, he often, when we visited in the early days, told us that he was there to conduct a review or an investigation, or that we were all at a conference that he had organised. That lifetime of leadership kept a hold even when so much else had been lost.

He had, from a young age, a sense of purpose, and one of his frustrations as his eyesight began to fail was that so many projects – travel abroad, or even ambitious UK walks like the ones that he and Cecily had done years before – were no longer practical or safe. For a while, writing his memoirs became his purpose, although in the final stages of the project dementia had begun to rob him not only of his memories but of understanding, and so I edited the document and arranged publication so that a copy could be placed into his hands whilst he could still recognise it as The Book, his own work.

John was fascinated by the natural world, greatly enjoying finding out about the flora and fauna – particularly the birds – of the parts of West Africa where we lived, and David Attenborough’s documentaries were a source of pleasure and interest in his last years. He read widely, and not only for professional purposes, and turned to audio-books after his sight loss, through which he enjoyed re-‘reading’ Dickens, Trollope, le Carré, Graham Greene and others, as well as discovering new writers (he was particularly enthralled by The Book Thief). He greatly admired the work of C P Snow, a scientist as well as a writer, who explored the idea of the two cultures, science and the arts (Snow’s novels were sadly not available in audio form). He loved music – as a young man he listened to jazz (New Orleans, and Django Reinhardt, not swing, as he told me firmly), but then was converted wholeheartedly to classical music after hearing Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos. Even in the very last stages of his illness he seemed to find calm in listening to Bach and Mozart in particular.

Just over a year ago, I wrote about Dad’s dementia, and specifically about Dad’s ‘raging against the loss of dignity, the loss of control over where he is and what happens to him, against the loss – even if he can no longer articulate it – of the things that made him him, against the slow dying of the light.’ And I expressed our heartfelt wish that his last days should not be spent ‘burning and raving at close of day’. In the end, at the very end, he did ‘go gentle into that good night’, with staff from his wonderful care home taking turns to sit through the night with him. We’re grateful for that, and that we each had the chance to say goodbye, to kiss him on his forehead and tell him that we loved him.

John is survived by his children Catherine, Aidan and Claire (youngest son Greg died of cancer in 2020), daughters-in-law Julie and Ruth, grandchildren Matthew, Arthur, Jordan, Melanie, Vivien and Dominic, step-grandson Tom, and great-grandchildren Jackson, Jesse and Eliza. He will be remembered with love by all of us.

2024 – Finding Joy and Hope

Posted by cathannabel in Personal on December 31, 2024

Since 2019 I have posted every week on Facebook a summary of the good things I’ve found over the previous seven days. This is always prefaced by an acknowledgement that these good things will most likely be small and personal, and that they will be outweighed in the grand scheme of things by all of the huge absolutely bloody awful things that are going on in the world. We can’t and mustn’t shut our eyes to the latter, even when for the most part they are things about which we can do very little. But if we’re going to get up each morning and wash and dress and face the world, or our little bit of it, it’s those small, personal good things that will give us the strength, day after day, to keep on keeping on.

In some ways the Good Things project is an odd one for me. I’m not a strenuously cheery person. If I am a ‘glass half-full’ person it’s an act of will because my brain is almost always in ‘what could possibly go wrong’ mode, and thus even much looked forward to events and experiences always have an element of anxiety attached. M used to say he was ‘glass half-full but really, really cross that it was only half full’. My late brother Greg was ‘glass overflowing’. So I suppose I’m ‘glass half-full but really quite worried I might tip it over and end up with glass empty’… Optimism is, as James Baldwin says, an act of will. It’s also, as Angela Davis put it, an ‘absolute necessity’. We might look at the world and see little reason for it – that’s what she called ‘pessimism of the intellect’ – but being alive, really living, requires optimism of the will. (My friend Mike Press reminded me of the Angela Davis quote, in a lovely piece he wrote about ‘reflection, renewal and optimism’.)

When I started my Good Things, my brother was dying of cancer. Then there was Covid and lockdown, and then, in October 2021, my husband Martyn died very suddenly of a heart attack. I could hardly have been more aware over these past few years that life wasn’t simply full of good things, even just on a personal level, and that wishing it wouldn’t make it so. But it helped me to have that discipline, that at the end of each week I had committed to finding something to write about, something that had brought me joy or comfort, something that had given me strength, something good. And I have always found something, even at the worst times.

In 2024 the huge absolutely bloody awfulness of what’s going on in the world is utterly daunting. When M was alive, we always watched the 10 o’clock news, but now, on my own, I find I rarely do. To watch together, and then head for bed and sleep with the comfort of each other’s company was one thing, to watch alone and then head for bed and sleep alone, with my mind full of Gaza and Trump and Ukraine and climate change and all of the other horrors is quite another. (I do read the papers every morning, I don’t shut my eyes to it all.) It’s hard to find good things out there, although I know that in any and every horror there are brave, good people who do whatever they can, at whatever risk to themselves, to mitigate that horror for others. We may not know who they are, but whilst history is very good at telling us of the evil that humans are capable of, it does also, if we look more deeply, tell us of those who stand against that evil. I try to hold on to that.

The word ‘joy’ keeps on cropping up at the moment. I recently watched the film with that title, about the first ‘test-tube baby’, whose second name was Joy, given to her by the surgeon who carried out the procedure. The film didn’t gloss over the wretchedness of infertility, and the people that the IVF process couldn’t help, but it acknowledged very movingly the joy that arrival brought, not only to her parents but to the team that had worked so long for that moment – and all of the people since who have had their chance at parenthood. And then the Doctor Who Christmas special this year was entitled ‘Joy to the World’, and it dealt with loneliness, loss and regret, but ended with light, and joy and hope. It seems to me that to have joy (as distinct from happiness, or contentment), one must know sadness, loss, pain as well, just as to be optimistic (as opposed to merely delusional) one must recognise it as an act of will, in the face of all the reasons for pessimism.

So where has the joy been, in 2024?

As always, in reading marvellous books, watching brilliant films and TV series, listening to wonderful music. There are lots of things that I enjoy, that pass the time pleasurably, but some that do more than that, that lift and move me more deeply. Hard to pick out just a few things, but, for example, Wim Wenders’ film Perfect Days, Paul Besley’s book The Search, choral music at St Mark’s Church, Chris McCausland dancing to ‘Instant Karma’ on Strictly…

Travelling with my son, for an amazing holiday, a three-city break in Vienna, Prague and Berlin, seeing the beauty of all three cities, and in each of them the tragedy of their wartime history.

Working with Under the Stars, a charity that works with adults with learning disabilities and autism through music and drama, seeing their music groups perform at Tramlines festival, at Yellow Arch Studios, at the Greystones pub and the Octagon Centre, and deejay/veejay at the Leadmill. It’s exhilarating and inspiring – their joy in performance is infectious.

Nottingham Forest. A change of manager – this time last year I wrote that ‘I’m hopeful that the new guy will enable us to stay up again this year’, but it turned out to mean a transformation that finds us at the end of 2024 second from top of the Premier League, and dreaming of possibilities in 2025…

Family – a wedding, an engagement, and lots of ordinary special times spent with the people I love most, watching football, watching Strictly, trips to the cinema, opera or theatre, going around the galleries in town, wine-tasting, meals out, meals at home. Boxing Day shared with the future in-laws for the first time.

Friends – meeting for coffee or lunch, sharing music, talking about families and plans, hopes and anxieties, meeting via Zoom when we can’t be together in person.

So this New Year’s Eve, as for the last approx. 40 years, will be shared with very dear friends. We’ll eat and drink and watch Jools’ Hootenanny and complain about his choice of guests, and on New Year’s Day we’ll eat more and find an undemanding film to watch before going forth into 2025. My first New Year’s Day without M was bleak, almost unbearably so. I faced the first year since I was 16 years old in which he would not be by my side. I expect there will be moments this New Year too, when it hits me, but three years on I am accustomed to being without him. It’s not that the grief and loss is less, rather that one adjusts around it, accommodates it, and it becomes a part of one. I know I will cope because I have coped already with so much, and because the people who’ve enabled me to cope will be with me.

And for 2025 we hope, of course we hope. We hope for cease-fires, for wars to end, for freedoms to be restored, for care for our planet to be prioritised over profit, for vital public services to be protected and rebuilt for those who need them. We hope for good things for ourselves and the people we love. We hope for the strength to cope when bad things happen, the strength that comes from other people’s love and support as well as our own.

I come back to this poem every new year. That word ‘sometimes’ has some heavy lifting to do here, but of course, sometimes, these things will be, and that’s what we have to hang on to.

Sheenagh Pugh – Sometimes

Sometimes things don’t go, after all,

from bad to worse. Some years, muscadel

faces down frost; green thrives; the crops don’t fail,

sometimes a man aims high, and all goes well.

A people sometimes will step back from war,

elect an honest man, decide they care

enough, that they can’t leave some stranger poor.

Some men become what they were born for.

Sometimes our best efforts do not go

amiss; sometimes we do as we meant to.

The sun will sometimes melt a field of sorrow

that seemed hard frozen: may it happen for you.

Hang on to your hat. Hang on to your hope. And wind the clock, for tomorrow is another day (E. B. White)

Three Cities – Vienna, Prague, Berlin

Posted by cathannabel in History, Personal, Second World War, The City, Visual Art on August 4, 2024

For most of my life, I’ve been fascinated by cities. My teenage years were spent in a rather ordinary dormitory village but I headed regularly for the nearest proper city (Nottingham) for shopping and football, and the annual Goose Fair. I’d previously lived in Kumasi (Ghana’s second city), and Zaria in the north of Nigeria. When I went off to University I settled in Sheffield where I still live, despite a few years commuting to Manchester, and a very brief period commuting to Leicester. My PhD thesis explored ideas about the city, about navigating and failing to navigate it, about the city as labyrinth, looking particularly at Manchester and Paris. And my idea of a really good holiday would be less likely to involve a beach (though a city that happened to have a beach would be quite appealing), but would definitely involve a lot of walking around in a city with heaps of history and culture.

A few years ago, I started to formulate an idea for such a holiday, encompassing two or three European cities, with as much as possible of the travel being by train. The idea never got very far when everything shut down, and we were barely starting to think again about travelling when M died, very suddenly, early one morning in October 2021. In the shock and grief that followed, I wasn’t really thinking about holidays in any practical way, but it did occur to me early on that they would be a challenge.

I can’t see myself travelling alone for any other than the simplest journeys. I take the train up to Dundee a couple of times a year to stay with friends, but always pick the direct trains, and I know I’ll be met at the station, and I went to Rome alone in December 2022, but was met at the airport, and had family to stay with. My biggest challenge in travelling alone is my highly deficient sense of direction. I got lost in Amsterdam on what should have been at most a ten-minute walk from my hotel to the conference venue – heck, I got lost in Leeds (with a similarly deficient friend) trying to get from the Trinity centre to the Grand Theatre. So the thought of a city break on my own is just too intimidating to contemplate – and of course the idea of getting lost in an unfamiliar city alone is something that triggers the hardwired caution that comes from growing up female. Add to this the fact that I am short and not particularly strong, and struggle with any case larger than a weekend holdall, so often have to rely on the kindness of strangers to get luggage on and off trains.

More than this, the pleasure of such a trip would be so diminished if I had no one to share it with. I’d need a travelling companion, and it would have to be a travelling companion who was (a) taller than me – not a major difficulty, most grown-ups are, (b) gifted with a good sense of direction, and (c) interested in the same sorts of things that I am, including with a high tolerance for WW2 history.

I said something about this dilemma one afternoon, sitting with my offspring, not long after M died. At which point the solution became obvious – my son A is (a) taller than me, (b) has an almost supernatural sense of direction and (c) is as much of a history geek as I am, with a similar interest in WW2. I started turning over in my mind what my ideal destinations would be, and Vienna, Prague and Berlin seemed to present the perfect mix of art, architecture and history, with a lot of WW2 and Holocaust sites to visit.

We started planning in earnest, once I’d checked with him that he wasn’t merely being kind when he agreed to go, but actually liked the idea, and worked out timings, and a wish list of places to go and things to see.

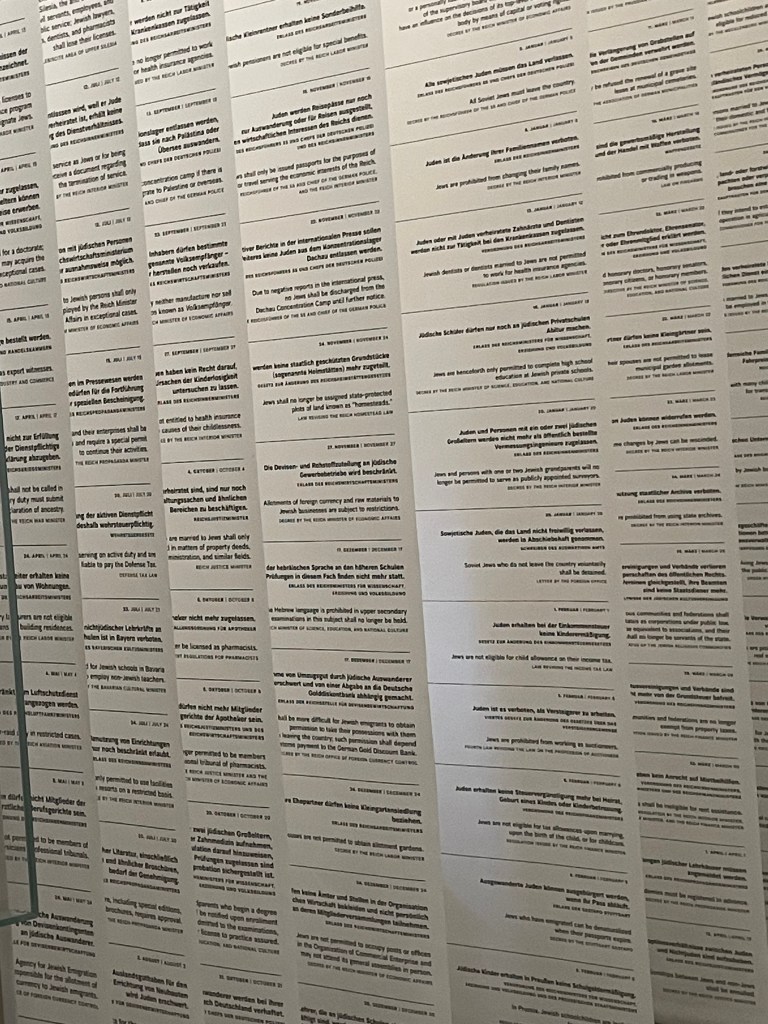

I decided, fairly early on in the planning, that whilst sites associated with the Jewish populations of those cities, and museums and memorials recording the destruction of those populations, were high on my list of places to visit, there would be no concentration camps. If I go back to Prague with more time, I will perhaps take a trip out to Terezín, but it was not a priority on this trip. A had visited Sachsenhausen on an earlier trip to Berlin (with school) but had no desire to go back again. This was the right decision – the history of those Jewish communities was less familiar to me than the history of the camps, and what I wanted was to honour the Jewish history of all three cities, and to see the people behind the statistics, in the Stolpersteine on the pavements, in the names on the battered suitcases from Theresienstadt, in the names painted on the walls of the synagogue.

This is a Holocaust heavy trip. I have been reading about and studying the Holocaust since I first encountered Anne Frank when I was probably around the same age as her, and I believe that if we do not understand it, or at least attempt to, we restrict and distort our understanding of post-war politics, history, art, literature and music, even of humanity. It was a significant thread in my PhD thesis, not just the Holocaust itself but how it can be written about, and I have often wrestled with the question of how – indeed, whether – fiction about the Holocaust can shed light. So, whilst I do totally understand why people would choose not to go to these sites, not to read those books or watch the documentaries, it is important to me to do so, to continue doing so. All that I have read, all that I know, has never desensitised me to its horror and it will never do so – the names and photographs, the individual stories, can and do still punch me in the gut. But I don’t go to these sites to get that gut punch, I go to continue to build my knowledge and understanding – and to pay my respects.

Part of my interest in visiting these three cities was to reflect on how they differ, and in particular how they approach their own WW2 history. Austria has described itself as Hitler’s first victim, but it is of course not quite that simple – there was enormous support for the Nazi party, and a long history of virulent antisemitism in Vienna, that ran alongside the major Jewish influence in culture and the arts as well as in business and politics. Czechoslovakia was, entirely straightforwardly, a victim of Nazi aggression, and Prague’s Holocaust memorial takes the form, most powerfully, of the names of the dead, painted on the walls of a synagogue. Berlin deals with its past – both the Nazi era and the injustices and brutalities of the DDR – with candour and without excuses, and its memorial is not about the Jews of Berlin or of Germany, but all of the murdered Jews of Europe.

This blog isn’t a guide to or a history of any of these cities. It’s an attempt to capture the experience, and my reflections on the experience, to help me remember it in all its richness. And I’ve included some of the research I did after we returned home, to find out, where possible, the stories behind the names on the Stolpersteine and other plaques, because for me this was a vital part of the trip. It is an entirely personal mix of anecdote, history, images and quotations and as such may not be a reliable source for anyone else’s city wandering…

Note: for clarity, I have used Terezín as the name of the Czech town, and Theresienstadt as the name of the Nazi ghetto/concentration camp which was created there. I have tried to be consistent with spellings, but Czech names are often to be found in multiple variants, so some inconsistencies may have slipped through.

VIENNA

We arrived on Monday evening, flew in from Manchester and got a train from the airport to the Hauptbahnhof, from where we just had to cross the road to get to our lovely hotel, Mooons (comfortable and welcoming – we were tired and a bit stressed after we’d checked in, having had a slightly less straightforward journey from the airport than we’d anticipated, and Sven the barman sorted out food and beers for us so we started to chill out and enjoy planning our time). We made the most of our two full days in the city – though there is plenty we didn’t see, buildings that we saw from the outside but didn’t go round, for example – I clocked up 59k steps, 40.5 kms. We managed to find some proper Viennese food – e.g. schnitzel and goulash, and good beer (I went for the darker beers, less lagery).

Tuesday:

From our very modern hotel, we were only a few minutes from the beautiful Belvedere Palace – we walked through the gardens which for me had strong Marienbad vibes (as in Alain Resnais’ French new wave masterpiece, Last Year in Marienbad, a film which has fascinated and haunted me for many years, and which I’ve previously blogged about on this site).

On to the Stadtpark, where we found a rather blingy statue of Strauss, and more tasteful ones of Bruckner and Schubert.

Clockwise: Mooons Hotel, Belvedere Palace, gardens and fountains, Last Year in Marienbad, Strauss statue in the Stadtpark.

Walking by the Danube – here there was graffiti, a lot of it political, e.g. re climate change. In general in Vienna, there was no litter, and an orderliness evident in what happened at pedestrian crossings, where no one walked until they were told to walk. It felt a lot safer than, say, crossing a road in Rome, where one feels as if the only way to ever get across is to walk and hope one isn’t immediately mowed down. (A told me of waiting in vain for the right moment at a crossing point in Rome, and another tourist facing the same dilemma saying cheerily, ‘OK, when in Rome…’ and launching himself into the traffic. The cars and bikes do weave around you but it never even starts to feel safe.)

There are two Jewish museums in Vienna. First up was the Museum Judenplatz, built around the excavated remains of the earliest synagogue in Vienna, destroyed in 1421 by order of Duke Albrecht V. It has a fascinating collection building up a picture of that early Jewish community, and of the exploration of the remains. The Jüdisches Museum nearby continues the story of Vienna’s Jewish population through the centuries. But there is a strange sense of a hiatus – not that the Holocaust is omitted but compared to Prague and Berlin, it is arguably underplayed, the job left to the bleak Whiteread memorial in the Judenplatz. This is a bunker, whose walls are made up of books with spines facing inwards to represent the victims whose names and stories are lost, 65,000 Austrian Jews. The names of the camps and other locations where they were murdered are inscribed around the memorial.

Stolpersteine (Schwedenplatz): Here there are three individual stones, and a plaque in memory of 15 unnamed Jewish women and men who lived here before they were deported and murdered (no details given) by the Nazis. The Stolpersteine commemorate Anna Klein, b. 14 Jan 1885, Josefine Steinhaus, b. 21 May 1884, Helene Steinhaus b. 3 August 1885. Deported to Maly Trostinec 27 May 42, killed 1 June 42. Maly Trostinec/Trostinets, a village near Minsk in Belarus, was not a location I was familiar with. Throughout 1942, Jews from Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia were taken there by train and then shot or gassed in mobile vans. According to Yad Vashem, 65,000 Jews were murdered in one of the nearby pine forests, mostly by shooting, but some estimates are much higher, up to 200,000.

Vienna State Opera (Staatsoper) We’d decided against trying to get tickets for any performance here because (a) cost, (b) I haven’t managed to entirely convert A to opera and (c) we didn’t want to commit an evening. That was the right choice – we walked for miles (see above), and in the evenings just wanted time to chill with some nice Austrian beers and talk over what we’d seen and make our plans for the following day. But the building itself is obviously magnificent. And we had seen inside anyway, in Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation…

Clockwise: Stolpersteine, graffiti by the Danube, Judenplatz, Whiteread Holocaust memorial, the Opera house and nearby street

St Stephen’s Cathedral (Stephansdom). As in Paris, the survival of this and other fine buildings was achieved by a refusal to carry out orders. The City Commandant had ordered the Cathedral to be reduced to rubble, but this was not carried out – unfortunately, as the Red Army entered the city, looters set fire to shops nearby, which spread and damaged the roof and destroyed the 15th century choir stalls. Much was saved, however, and reconstruction began immediately after the war, with a full reopening in April 1952.

Watching The Third Man makes one realise just how badly Vienna was damaged during the war – not devastated like Berlin, Hamburg, Dresden, but, as Elisabeth de Waal puts it, ‘desultory bombing by over-zealous Americans on the verge of victory, and the vindictive shelling by desperate Germans in the throes of defeat’ had resulted in ‘the gaps in the familiar streets, the heaps of rubble where some well-remembered building had stood’ (The Exiles Return, p. 57). One would not know it now. Clearly, given the fear that rebuilding would destroy the character of the city, the choice was made to rebuild it as it had been, as far as possible. Which gives Vienna that feeling of being preserved in aspic, a slight unreality.

We went a bit further afield, out to Schonbrunn Palace. We didn’t go round the palace itself, preferring to explore the gardens, and head up the hill to the Neptunbrunnen and the Gloriette, to enjoy the view, which was indeed glorious.

Clockwise: Schonbrunn Palace, Gloriette and Neptune fountain; Stephansdom

Maria am Gestade church – one of the oldest churches here, built 1394-1414

Memorial to liberating Soviet soldiers (Heldendenkmal der Roten Armee/Heroes’ Monument of the Red Army), in Schwarzenbergplatz, featuring a twelve-metre figure of a Soviet soldier. This was unveiled in 1945. It seemed to me remarkable that it was built so soon after the war ended, but then I hadn’t realised either that Vienna was liberated by the Red Army, or that in the hiatus before the other Allied Forces arrived, there was a real possibility of Stalin occupying all of Vienna. The memorial is about heroism in battle, not about the violence, particularly sexual violence, inflicted on civilians during and after the battle, and has been controversial and subject to vandalism over the years, including very recently in response to the invasion of the Ukraine.

Wednesday:

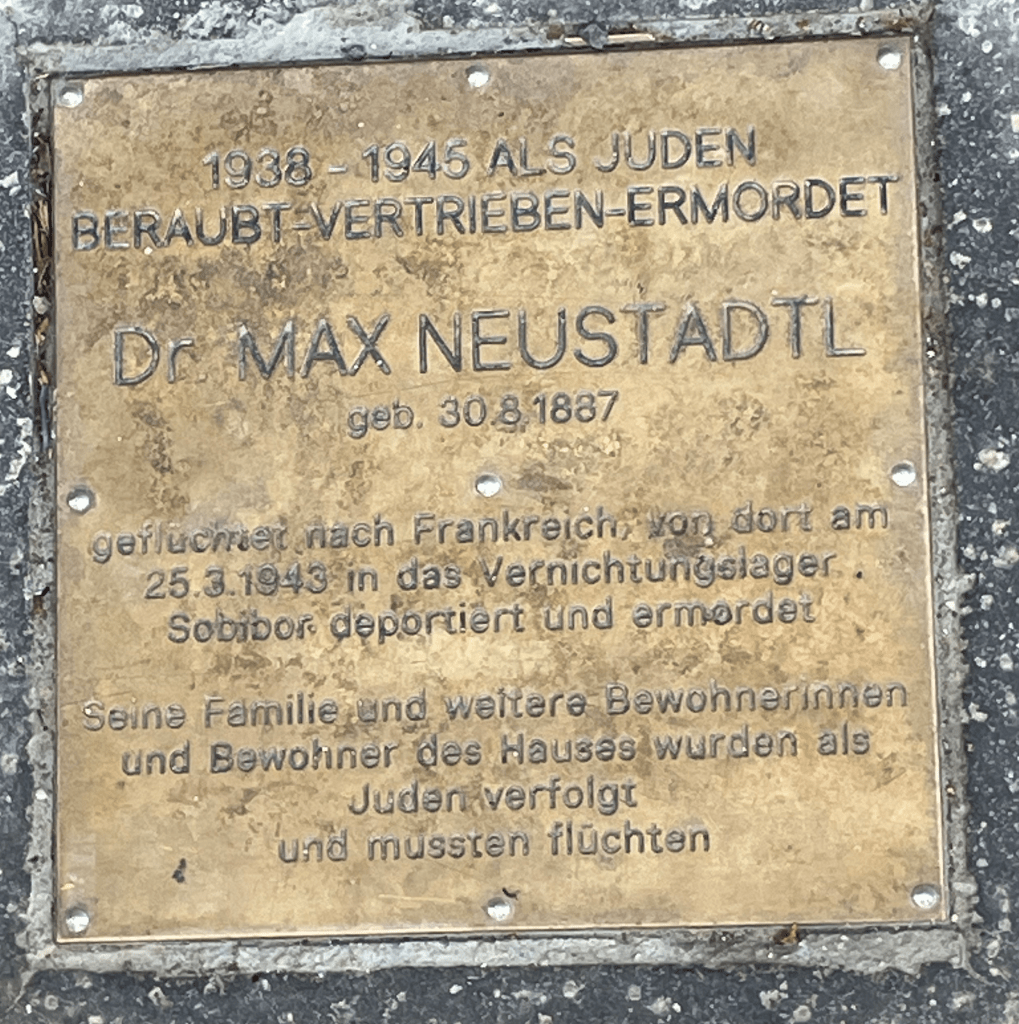

Stolpersteine: Paula Wilhelm (née. Mandl), born 6 April 1887, deported 29 April 44 to Auschwitz; and Dr Max Neustadtl who fled to France but was deported on 25.3.43 to the Sobibor extermination camp and murdered.

Vienna’s second Jewish Museum focuses on the later Jewish communities, covering the period of Nazi rule, but not dealing in great depth or detail with the Holocaust.

One fascinating display here is part of the collection of netsuke whose story is told in Edmund de Waal’s The Hare with the Amber Eyes. These are the Japanese miniature sculptures which belonged to the Ephrussi family, and which were kept out of the hands of the Nazis, unlike most of the contents of the Palais Ephrussi. Six weeks after the Anschluss, the family servant, Anna, was required to pack away the belongings of her former employers. There were lists, of course, to ensure that everything was accounted for. But each time that Anna was in the Baroness’s dressing room, she slipped a few of the netsuke into her apron pocket, and hid them in her room. In December 1945, Anna gave Elisabeth de Waal 264 Japanese netsuke.

‘Each one of these netsuke for Anna is a resistance to the sapping of memory. Each one carried out is a resistance against the news, a story recalled, a future held on to.’ (Edmund de Waal – The Hare with the Amber Eyes, pp. 277-83)

Clockwise: Stolperstein for Max Neustadtl, netsuke in the Jewish museum, Maria am Gestade church, stolperstein for Paula Wilhelm, Heroes Monument of the Red Army

A plaque on Herminengasse gives the names of Jews who lived here, in what was once part of the Jewish ghetto. Many Viennese Jews were forced to live here, until they were deported to various killing sites. Several were killed in Izbica (a town in Eastern Poland, which was turned into a ghetto) – all show the same date of death, 5 December 1942, when the inhabitants of the ghetto (Polish Jews, and those deported from Germany and Austria) were murdered. Those who escaped this massacre were deported again, to Treblinka, Maly Trostinec, Łódź Ghetto, Riga Ghetto, Theresienstadt, Sobibor, Stutthof. I know nothing about these people, other than their age, and where they were killed. But I can see that Oskar Koritschoner was only 20 years old when he committed suicide. Maly Trostinec was the place where 13-year-old Regine Frimet and 3-year-old Ernst Elias Sandor were murdered. And Josef Weitzmann, the last of these to die, was killed in Stutthof concentration camp, in 1944, just after the facilities for mass murder had been set up there. He was 18.

We found the Palais Ephrussi, on the Ringstrasse (see, again, The Hare with the Amber Eyes). I had had an insight into the efforts to trace the plundered contents of the Palais, from Veronika Rudorfer who I met in December 2019 at a conference, when she gave a talk on that project, and subsequently, very generously, sent me a copy of her beautiful book about the Palais itself.

The Burg Theatre – Sarah Gainham’s excellent novel Night Falls on the City has a lot of the action taking place at the Burg theatre, as her protagonist is one of its leading actors. One wouldn’t know that this building was largely destroyed in bombing raids during WW2, and then by a fire subsequently, and has been rebuilt.

Votivkirche (Votive Church) is a gorgeous, somehow delicate looking church, one of the most beautiful in a city of beautiful churches. It is in a neo-Gothic style and was built to thank God for the Emperor Franz Joseph’s survival of an assassination attempt in 1853.

Clockwise: Burg Theatre, Herminengasse plaque, Palais Ephrussi, Votivkirche

We saw the Rathaus – Vienna City Hall – and walked through the Burggarten where we found a statue of Mozart. Then the Resselpark (Karlsplatz), where we saw Sarah Ortmeyer and Karl Kolbitz’s 2023 memorial for homosexuals persecuted by the Nazis: ‘Arcus – Shadow of a Rainbow’, the colours of the rainbow changed to grey, combining grief and hope. There’s also a Brahms statue here, which I like very much.

On to Heldenplatz (Heroes Square), in front of the Hofburg Palace.

‘The two over lifesize equestrian statues on high pedestals are what give it its name, two great military commanders on rearing horses with flowing manes and tails in the Baroque style, one carrying Prince Eugene of Savoy and the other the Archduke Charles, brother of the first Emperor Francis who, in one victorious battle, had stemmed for a while Napoleon’s advance on Vienna. … And yet, with all their panache, there is so little boastfulness in this square. What first meets the eye and impresses the mind are the broad avenues of chestnut trees lining it on three sides … They give the square its peaceful, almost countrified look; they are conducive to slow perambulation and quiet contemplation.’ (Elisabeth de Waal – The Exiles Return, p. 227)

In sharp contrast to the above description, this is where Hitler made his announcement of the Anschluss after his triumphant arrival in the city.

Clockwise: Brahms statue in Resselpark, Heldenplatz, Mozart statue, Rathaus, Arcus memorial in Resselpark

Parliament Building – another building that was seriously damaged in WW2 and the restored to its former glory. In front of it is the Pallas Athene Fountain – apart from Athene (statuary in Vienna is often Graeco-Roman in subject matter and style) it represents the four major rivers, the Danube, Inn, Elbe and Vltava (Moldau in German).

Hofburg Imperial Palace – the official residence and workplace of the President.

Schwarzenberg Monument, commemorating Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg’s victory at the battle of Leipzig in 1813. Yet another equestrian statue (I cannot help it if the Bonzo Dog Doodah Band come to mind when I see these).

Here comes the Equestrian Statue

Prancing up and down the square

Little old ladies stop ‘n’ say

“Well, I declare!”Once a month on a Friday there’s a man

With a mop and bucket in his hand

To him it’s just another working day

So he whistles as he rubs and scrubs away(hooray)

(Bonzo Dog Doodah Band, ‘The Equestrian Statue’ (N. Innes), Gorilla, 1967)

Haus der Musik (Klangmuseum – museum of music and sound) is in the Palace of Archduke Charles, where the founder of the Vienna Phil lived around 150 years ago. The focus is on composers for whom Vienna was significant, with interesting material on Beethoven, Schubert, Mozart, Mahler, Schoenberg and others (not just biographical), as well as fun stuff about the science of music, my first encounter with a virtual reality headset (I didn’t do very well).

Clockwise: Haus der Musik, Archduke Charles monument, Hofburg palace (official residence and workplace of the President), Pallas Athene fountain, Parliament Building, Schwarzenberg monument

Kunsthistorisches Museum – in a palace (of course), purpose built by Emperor Franz Joseph 1 to house the rooms full of antiquities, sculpture and decorative arts. But the highlight was the picture galleries, and especially the Breughels, an absolute joy to see ‘Hunters in the Snow’ etc close up. Also paintings by van Eyck, Raphael, Durer, Holbein, Titian, Caravaggio…

What did we miss? Well, if I went back, I’d go to see the Klimts in the Belvedere gallery, I’d book a tour of the Opera House, and the Parliament building. Might even go on the Riesenrad (I think given the particular form my vertigo takes – see below – I would be OK with it, after all, I was fine on the London Eye).

Vienna Reading: Fiction: Sarah Gainham – Night Falls on the City/Private Worlds; Elisabeth de Waal – The Exiles Return. Non-fiction: Clive James – ‘Vienna’, in Cultural Amnesia; Edmund de Waal – The Hare with the Amber Eyes; Claudio Magris – Danube; Stefan Zweig – The World of Yesterday

Vienna on Film: The Third Man; Before Sunrise; Vienna Blood (TV detective series set in turn of the century (19th-20th) Vienna)

Vienna Music: Too much to mention – the city played such a key role in the lives and careers of so many great composers and musicians. Beethoven, Mozart, Schoenberg, Schubert, Brahms, Webern, Korngold… I did my best to avoid hearing ‘The Blue Danube’, a piece I heartily dislike, whilst in Vienna, but didn’t quite manage it (it’s a bit like trying to avoid hearing Wham at Christmas)

One lesser-known name, who I researched on our return. Marcel Tyberg was born and studied in Vienna but moved to Italy (present day Croatia) in 1927, when he was in his thirties. His mother followed the rules once the area was under Nazi occupation, and registered her Jewish great-grandfather. She died of natural causes, but Tyberg was arrested and deported, first to San Sabba camp in northern Italy, and then to Auschwitz, where he was murdered in December 1944. I listened to the Piano Trio in F major (1935-1936).

PRAGUE

Thursday:

We set off early to catch the train to Prague. Not the most scenic of journeys but travelling by train makes the journey part of the holiday and is generally less stressful. That is, once I was on board – the ‘mind the gap’ warnings do not adequately convey the hideous gulf between the train and the platform which involves one stepping out into said gulf and on to a narrow step before reaching the safety of the train. I realised this at Vienna Airport station but had vainly hoped that this wasn’t going to be the case with all the trains we caught… Fortunately A is both capable and caring, and so he grabbed the bags, put them into the train and then held my arms and made me look at him, not at the gulf, and step in. Same procedure in reverse when we got off the train, of course.

A slightly longer walk from the station to our hotel, the Majestic, near Wenceslas Square. A more old-fashioned looking hotel than Mooons but very comfortable. Having deposited our bags we set off for the Old Town. What I hadn’t anticipated is how much harder on the feet and the joints the cobbled streets in Prague would be – both of my days in the city had to be curtailed slightly early because on that first day there I crocked myself a bit. I still managed to clock up 17k steps (not bad for a half day), and 20k the following day, a total of 25.5km in the city.

Walking around Prague felt very different to walking around Vienna (and not just because of the cobbles). It is a city to wander in, to stroll down random streets, look around random corners, and be beguiled and intrigued by buildings that are a jumble of styles and eras, shapes and sizes. The terms ‘new’ and ‘old’ in Prague tend to mean ‘old’ and ‘really, really old’.

Clockwise: Charles Square, St Adalbert’s Church, Hotel Majestic, New Town Hall, view of the Zofín palace, a mysterious and ominous sign across the Vltava

Charles Bridge is always rammed with tourists – it is probably the most photographed site in the city, understandably enough. We got glimpses of it from the New Town side on Day 1, and the Prague Castle side on Day 2, when we did go part of the way across.

Jan Palach memorial, Wenceslas Square. I was 10, going on 11 at the time of the Prague Spring. I remember the news reports, and my parents’ distress (they vividly remembered the events in Hungary in 1956), and I remember hearing of Jan Palach’s suicide. A couple of years later, the English teacher at my school, an eccentric chap called Mr Pepper, mentioned this (I cannot recall in what context) and said that in a few years, no one would remember Jan Palach’s name. I decided that I would. And I did.

The Jewish Museum in Prague, based in the old Jewish quarter, comprises a number of locations – we didn’t see everything, but what we did see was unforgettable. It comprised four synagogues, the ceremonial hall, the old Jewish cemetery (and a gallery which was closed when we visited).

Pinkas synagogue – I knew what I was going to see. But that didn’t make it any easier. I wrote back in 2017 about a visit to the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris: ‘I had braced myself for this, knowing the terrible history that would be illustrated there. Nonetheless, seeing the Wall of Names, I felt the air being sucked from my lungs, realising that I was seeing in that moment only a fragment, only some of the names from only one of the years’. That’s how I felt in the Pinkas synagogue, where the Memorial to the Victims of the Shoah from the Czech Lands comprises their names on wall after wall after wall. The names are painted on, which gives them a certain fragility, that they could fade away, unlike the stones in the Paris memorial. They mustn’t, obviously. They need to be there for generation after generation, to see wall after wall of names, each a person with a story, with a life, with a potential future.

‘The storm is within, a blizzard that stings the eyes and batters on the mind. Not snow or sleet but names. Names everywhere, names on the walls, names on the arches and the alcoves, ranks of names like figures drawn up on some featureless Appellplatz. Names and dates: given names and dates in black, surnames in blood. Dates of birth and dates of death. Seventy-seven thousand seven hundred and ninety-seven of them, names so crowded that they appear to merge one into the other and become just one name, which is the name of an entire people – all the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia who died in the camps.’ (Simon Mawer – Prague Spring, pp. 218-19)

From the Pinkas synagogue to the old Jewish cemetery, in use from the first half of the 15th century till 1786 – the oldest gravestone is from 1439. It’s the ‘Prague Cemetery’ which gives Umberto Eco’s novel its name (a book that is now on my To Read list). (We didn’t visit the New Jewish cemetery to pay our respects to Kafka – maybe next time, especially if I manage to read a few more of his works before then). We saw the Jewish ceremonial hall, and the Klausen synagogue but didn’t go in. But we couldn’t miss the ornate gorgeousness of the Spanish synagogue, whose decoration imitates the Alhambra.

Clockwise: Pinkas Synagogue, Jan Palach memorial, Jewish ceremonial hall, Old Jewish cemetery, Spanish synagogue

The Old Town Hall is actually a medley of a number of buildings of various sizes and ages, stitched together (if I may mix my metaphors) over the centuries. At various times, bits of it were demolished/rebuilt/amended in various ways. In 1945 during the uprising in the city, a couple of wings were destroyed by fire. On another visit, I would be very intrigued to look around this properly.

The Town Hall’s most famous feature is the rather marvellous 15th century Astronomical Clock. We missed its most marvellous moment though as we failed to be there at the right time to see the apostles emerge.

Stolpersteine (Nové Město): four members of the Gotz family. Rudolf was 49, and his wife Marie 48 when they were deported from Prague to Theresienstadt; two years later both were transported to Auschwitz where they were murdered. Their sons Raoul and Harry made the same journeys at slightly different times than their parents. They were 21 and 16 respectively when they were deported, four months before their parents, to Theresienstadt, and then in September 1943, a year before their parents, to Auschwitz.

Clockwise: Astronomical Clock, Church of St Nicholas, stolpersteine for the Gotz family, Kranner’s Fountain (monument to Emperor Francis 1 of Austria), the Old Town Hall, Old Town Square

At this point, I consented to return to the hotel and put my feet up, whilst A headed off to the Prague Museum.

Friday:

Day 2 – with my feet properly blister-plastered, and a comfier pair of shoes, we headed (via the tram) to the Prague Castle complex. There’s a lot to see here, and the views of the city are stunning.

We walked through the Royal Gardens, with beautiful buildings around them, including Queen Anne’s Summer Palace. We saw a red squirrel here – I’m honestly not sure that I’ve seen one before, but we then saw another in Berlin.

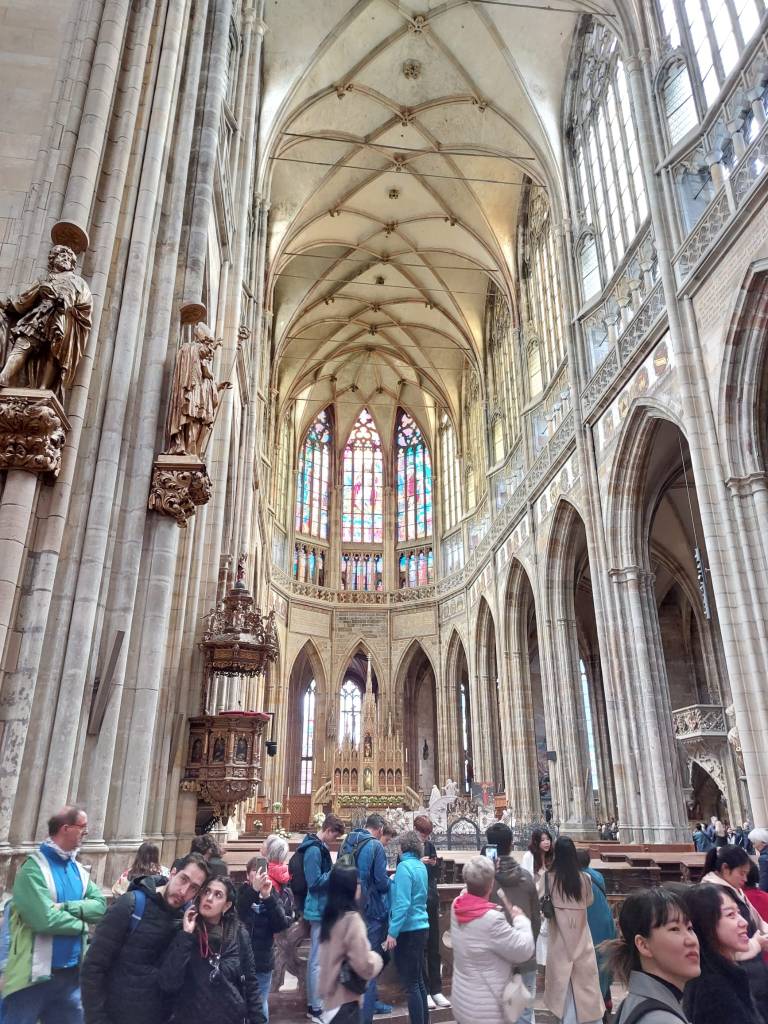

St Vitus Cathedral – this took nearly 600 years to complete, 1344-1929. One of the final stages involved the installation of the beautiful stained glass. Czech art nouveau painter Alfons Mucha decorated the windows in the north part of the nave, František Kysela the rose window. Even though half of the cathedral is a neo-Gothic addition, much of the 15th century design was incorporated in the restoration.

Going up the Great South Tower was an optional extra which I unhesitatingly declined. I have been frozen with fear on spiral staircases in many of the ancient buildings of Britain, and in the Arc de Triomphe (with a posse of French schoolkids behind me helpfully going ‘Allez! Allez!’). So I let A go up the tower – there were a lot of steps, and it was indeed a spiral, but worth it (he tells me) for the view from the top.

The Basilica of St George is the oldest church building on the castle site, dating from 920.

Clockwise: Basilica, Cathedral interior, Cathedral, Great South Tower, Royal Gardens, stained glass in the Cathedral, Chapel of the Holy Cross, Castle interior, Queen Anne’s Summer Palace

Golden Lane is a pretty alleyway of tiny, brightly coloured cottages. These were built for the members of Rudolf II’s castle guard and takes its name from the goldsmiths who later occupied the cottages. Kafka came here in the evenings to write, during the winter of 1916.

12 Šporkova is the building where W G Sebald’s Austerlitz found the apartment that his parents had occupied. The fictional Jacques Austerlitz left Prague in 1938 to come to the UK as part of the Kindertransport. He was brought up without knowing anything of his origins but becomes haunted by the absence of his past and starts to search for information about his parents.

‘The register of inhabitants for 1938 said that Agáta Austerlitz had been living at Number 12 in that year… As I walked through the labyrinth of alleyways, thoroughfares and courtyards between the Vlašská and Nerudova, and still more so when I felt the uneven paving of the Šporkova underfoot as step by step I climbed up hill, it was as if I had already been this way before and memories were revealing themselves to me not by means of any mental effort but through my senses, so long numbed and now coming back to life.’ (W G Sebald, Austerlitz, pp. 212-13)

Austerlitz finds his old neighbour, and learns that his mother was deported to Theresienstadt, and from there to Auschwitz. His father had already left for France before his own escape, and by the end of the book Austerlitz is still searching for information about whether he survived (or how he died).

We didn’t knock to try to go in and see if the hallway and stairs are as Sebald described – in any event, I don’t know whether Sebald himself ever did so. There are a couple of photographs embedded in the text but as always with Sebald, we can’t assume that their positioning tells us what they are. Sebald visited Prague in April 1991, and again in April 1999, at a time when he would have been writing Austerlitz, and it seems likely that he at least did as we did and wandered down Šporkova and looked at the doorway. But did he choose this location arbitrarily, or did he have some information about its past that encouraged him to link it to his fictional protagonist? As always, Sebald mingles fact and fiction in a most fascinating, infuriating, and sometimes highly problematic way (see my PhD thesis for (much, much) more on this topic!).

Estates Theatre – another Sebald connection: Austerlitz’s mother was an actress who performed at the Estates Theatre. It dates from the 1780s, and saw the premieres of Don Giovanni and La Clemenza di Tito, as well as the first performance of the Czech national anthem. It can also be seen in the film of Amadeus during the concert scenes, standing in for Vienna, as it is one of the few opera houses in Europe still intact from Mozart’s time.

I didn’t see the extraordinary Dancing House myself – on day 2 in Prague I again had to bail early (those bloody cobbles), and so A went on alone, to see this building which had intrigued him from the guidebook. The Dancing House, or Ginger and Fred, was designed by architects Vlado Milunić and Frank Gehry on a vacant riverfront plot in 1992 and completed in 1996.

Clockwise: 12 Šporkova, the Dancing House, Estates Theatre, Golden Lane, Prague Museum, Morzin and Thun palaces.

A also visited the Ss Cyril & Methodius Cathedral, site of the last stand of seven members of a Czech resistance group including Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš, who had assassinated Heydrich. They were betrayed, and the church was surrounded by 750 SS soldiers, water pumped into the crypt to try to force them out, until all were killed or had committed suicide. We were both familiar with their story from the film Anthropoid – I’d also read Laurent Binet’s HHhH, and seen the film adaptation of that, The Man with the Iron Heart.

Wenceslas Square, near our hotel. The site of celebrations and demonstrations, and home of the statue of St Wenceslas (this isn’t the original one – that was moved elsewhere in 1879, this one dates from 1912). The National Museum, which A visited on Day 1, is at the top of the square.

Clockwise: Charles Bridge, the crypt of Ss Cyril & Methodius Cathedral, Memorial to the Czech resistance, Ss Cyril & Methodius, Wenceslas Square, Prague viewed from the Castle

What did we miss? We only saw the modern part of Prague station, not the older building, nor the Kindertransport memorials there. We didn’t get to Petrin, and the funicular railway, the observatory, mirror maze or the mini Eiffel Tower (Rozhledna). But if we come back, we’d probably just spend more time wandering, I think, because there’s something to see around every corner here, not necessarily something grand like in Vienna, but something intriguing, something beautiful, something memorable.

Prague Reading:

Fiction: Lauren Binet – HHhH (a fictionalised account of the assassination of Heydrich); Franz Kakfa – The Castle (it’s not really about Prague Castle but still…); Simon Mawer – Prague Spring; W G Sebald – Austerlitz; Philip Kerr – Prague Fatale; Heda Margolius Kovaly – Innocence (a Prague-set detective noir). Non-Fiction: Anna Hajkova – The Last Ghetto: An Everyday History of Theresienstadt; Heda Margolius Kovaly – Under a Cruel Star (also published as Prague Farewell), her autobiography, covering imprisonment in the Łódź ghetto and Auschwitz, her return to Prague and the judicial murder of her husband during the Slansky show trials, finally leaving after the failure of the Prague Spring; Alfred Thomas – Prague Palimpsest: Writing, Memory and the City (especially Ch. 5 which deals with Sebald’s Austerlitz).

Prague on Film: Anthropoid; The Man with the Iron Heart; Kafka (TV series)