Archive for category Literature

2020 Books – half-time report

Posted by cathannabel in Literature on July 1, 2020

We’re halfway through this strange, sad year. In theory, there’s been more time for reading since lockdown. But at times this year, not just due to Covid, I haven’t found it easy to focus on a book. Nonetheless, I’ve read a lot, and these are some of the highlights. In general, they reflect my need for what the brilliant Attica Locke recently described (in a tweet about Nicole Dennis Benn’s lovely novel Patsy, which I am reading at present) as ‘uplift with heft’. Too cosy and too obviously intended to be ‘heartwarming’ and I get angry, because life isn’t cosy, things don’t always work out OK, people die, people are sick, people are broken. Too grim and I just can’t bear it, not now, not in the midst of all this. There has to be something that lifts me up, some element of hope, the possibility of change for the better, the capacity of people to exceed one’s expectations, to be better and to do better.

There’s only one title here that specifically references the pandemic. But several of the fiction and non-fiction titles reflect my realisation part way through the year that my reading so far had been dismayingly white. It seemed appropriate, in the midst of the #BlackLivesMatter protests worldwide, to address that.

This isn’t everything I’ve read. I’ve missed a few re-reads, and I have, as I always do, omitted things I found mediocre, or clunky. This is the good stuff.

Fiction

Melanie Abrams – Meadowlark. A bow drawn at a venture, and a thoroughly good read. Like Glaister’s Chosen, it’s exploring the world of closed communities (aka cults), how seductive and deadly they are.

Belinda Bauer – The Shut Eye. A missing child mystery that doesn’t follow the path you expect, that is troubling and puzzling and shocking in all sorts of ways. Bauer is described by the Independent as ‘either so quirkily idiosyncratic – or just plain bloody-minded – that [her] books resolutely resist conforming to whatever the latest modishness is’.

Nicole Dennis-Benn – Patsy. I’m reading this on the recommendation of Attica Locke, as mentioned above. Patsy is a Jamaican immigrant in New York, living the precarious life of the undocumented, a life that separates her not only from her home and family, but from the hopes that brought her here.

Alan Bennett – The Uncommon Reader. This made me laugh, rather a lot, at a time when laughter was in short supply. Brilliantly witty and sharp, it also manages to be oddly touching.

Arnold Bennett – Hilda Lessways. This is Part 2 of his Clayhanger series, written in 1911, set in the Midlands in the late 19th century, with a female protagonist who blazes off the page.

William Boyd – Love is Blind. This is a tour de force, and my favourite of his books so far. It’s clever, but never just clever. ‘Audaciously unpredictable’ as the Guardian put it. The narrative takes us from Victorian Scotland to Paris to Russia and to the Bay of Bengal, it’s romantic and vivid, and totally engaging.

NoViolet Bulawayo – We Need New Names. Fine, powerful writing – and with humour amongst the grim. The trajectory is familiar – the African diaspora, in this case from Zimbabwe to the USA, but the voice is fresh.

Jane Casey – The Cutting Place. The latest Maeve Kerrigan, and quite possibly the best yet (I probably say that each time, but the series really does keep upping its game).

Lissa Evans – Old Baggage. A writer I’ve discovered only recently. I read Spencer’s List earlier this year, and after Old Baggage, I read its sequel, Crooked Heart, and eagerly await V for Victory in August. Funny and moving, with characters that get under your skin and into your head and your heart.

Nicci French – The Lying Room. This is the first I’ve read from the husband and wife team of Nicci Gerrard (who I know as a campaigner for dementia patients in hospital, and author of the powerful and moving What Dementia Teaches us about Love) and Sean French. And very good it is too – steeped in secrets and lies. I will read more.

Tana French – The Trespasser. Latest in the splendid Dublin Murders series. Though we call it a series, French’s distinctive technique is to shift the focus from novel to novel, so that a peripheral character in one becomes the main protagonist in the next.

Patrick Gale – Take Nothing with You. One of his best. And the writing about music is so vivid that I could almost hear it as I read.

Lesley Glaister – Chosen. The latest from a favourite writer whose work I’ve been following for many years, a gripping and intense psychological thriller, like Meadlowlark, exploring a closed community. Very twisty.

Elizabeth Goudge – The Bird in the Tree / The Herb of Grace / The Heart

of the Family. First read when I was a teenager, and returned to in the hope of ‘uplift with heft’, The Eliots of Damerosehay trilogy is mystical, romantic, intense – all about hope, and the redemptive power of place

to heal broken humans.

Elly Griffiths – The Lantern Men. The new Ruth Galloway. Always feel like I’m meeting up with a friend when I read these, I’d love to go down the pub with Ruth (when that sort of thing becomes normal again, obviously). And of course, there’s a splendid mystery, and the cast of supporting characters is drawn with humour, insight and affection.

Yaa Gyasi – Homegoing. I’ve had this one in my TBR pile for a while, but it felt as though this was the time to open it. It’s a complex narrative, on a huge scale (centuries, continents). It starts, though, in places that resonate with my own childhood in Ghana in the early 60s – Cape Coast Castle and Kumasi. Often harrowing, always compelling.

Emma Healey – Whistle in the Dark. By the author of the excellent Elizabeth is Missing, a mystery with an ending that is both terrifying and moving.

Mick Herron – Dead Lions. Second in his Slow Horses series, about a department of MI5 rejects – acerbically funny but without pulling any emotional punches.

Susan Hill – The Benefits of Hindsight. The latest in her excellent Simon Serailler detective series, as always musing on mortality and morality whilst solving the crime.

Judith Kerr – Out of the Hitler Time. This is a trilogy of lightly fictionalised autobiography by the late and dearly beloved author of Mog and The Tiger who Came to Tea, starting with the Kerr family’s narrow escape from Nazi Germany.

Philip Kerr – Metropolis. Sadly the last in the brilliant Bernie Gunther series of detective novels set before, during and after the Nazi era.

Stephen King – If It Bleeds. This guy is unstoppable. A collection of short stories, two of which are kind of standard King – which is still a very good thing – and two of which are classic King which is brilliant.

John le Carré – Legacy of Spies. One more, probably last, Smiley novel from the master. It has an elegiac tone, including a final eulogy to the dream of European collaboration and unity.

Andrea Levy – The Long Song. Very powerful and moving. I loved the storyteller’s voice, the dialogue and the ongoing arguments between her and the person who’s pressing her to tell the story, the gaps that can’t be filled.

Laura Lippman – The Lady in the Lake. Another excellent psychological thriller from Lippman, a polyphonic narrative, using glimpses of events from a number of different points of view to complement or contradict the protagonist’s perspective.

Attica Locke – Pleasantville. Sequel to Black Water Rising, which I read last year, it picks up the story of black Texas lawyer Jay Porter fifteen years after the events of that book. It’s a riveting plot, with a great cast of complex characters and the ability to move between state politics and the domestic exigencies of single parenthood with grace and perception.

Adrian McKinty – The Cold, Cold Ground. First of his Belfast-set Sean Duffy crime series, which I will definitely be following up.

Denise Mina – Still Midnight. Starts with an Asian family facing a home invasion, doesn’t go where you expect it to, gets hold of you and doesn’t let you go till the last page.

Sarah Moss – The Tidal Zone. I properly got into Moss last year and this year have read The Ghost Wall and this one, which is entirely different again (one never does know quite what to expect with Moss). As the Guardian says, this is a novel about the NHS, which makes it rather timely, and about parental anxiety, but also about art, and ideas.

Maggie O’Farrell – This Must be the Place. Always brilliant. Not my top O’Farrell but excellent. As the Guardian says, she is ‘a deft and compelling chronicler of human relationships’.

Louise Penny – A Fatal Grace. The second in the Inspector Gamache series, set in a small Québécois town. They’re not at the gritty end of crime fiction (it’s been said that they’re modelled on the classic British whodunit) but that doesn’t mean they’re superficial or cliched.

Susie Steiner – Remain Silent. We’ve had a long wait for the new Manon Bradshaw but it was worth it. Manon is a tremendous, real, often abrasive and annoying central character. And one can’t be unaffected by the knowledge that Steiner has been undergoing treatment for a brain tumour, and that the latest news is not good.

Elizabeth Strout – Olive Kitteridge. I read Abide with Me last year, and this is the third Strout I’ve read this year. Exceptionally good, deeply empathetic, a novel in interlinked short stories (like Anything is Possible).

Meg Waite-Clayton – Beautiful Exiles. This is a fascinating novel about the formidable Martha Gellhorn. Gellhorn hated being described as the third Mrs Hemingway, so I did wish that Waite-Clayton had continued the story after she finally dumped Hemingway…

Elizabeth Wein – The Enigma Game Another brilliant WWII YA novel from the author of Code Name Verity. Thrilling and moving stuff.

Colson Whitehead – The Nickel Boys. This one I think even surpasses The Underground Railroad. It’s devastating. Brilliantly constructed, and with a twist that’s no gimmick, and a protagonist who you want so very badly to be OK whilst knowing the odds against that…

Non-Fiction

Chimanada Ngozi Adichie – Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions. My favourite contemporary African writer, passing on her thoughts on feminism to a friend, who’s asked her advice on raising a daughter. The feminism itself isn’t revelatory but Adichie is writing from within the Nigerian Igbo culture that she and her friend share, and that makes it fresh and engaging.

Angela Davis – Women, Race and Class. Davis was one of my heroines, when I was educating myself about the civil rights movement as a teenager. She was, and is, awesome. This was written in 1983, and it’s ahead of the game in terms of what we would now call intersectionality, tracing the connections between the abolitionist movement, the suffragists, and the civil rights struggle to show how those priorities, those needs, coincided or conflicted.

Dorothy Day – The Long Loneliness. I knew absolutely nothing about Day until my son discovered her, whilst doing an MA in American History. She was a remarkable woman – a Catholic socialist anarchist, a journalist and activist, who co-founded the Catholic Worker Movement, and faced controversy for her refusal to support Franco in the Spanish Civil War. This autobiography was published in 1954 (she died in 1980). As baffling as I find her religious faith, her account of the social and political upheavals in which she was involved is fascinating.

Jason Diakite – A Drop of Midnight. Another fascinating memoir from someone I hadn’t heard of! Diakite is a black Swedish rapper, and here he explores his family history and his father’s roots in the American south, and musing on music, race, and the importance of shiny shoes.

Lara Feigel – The Love Charm of Bombs. The Blitz through the eyes of writers (including Graham Greene and Elizabeth Bowen) who lived through it and did their bit in some way (air-raid wardens, ambulance drivers, etc). The most interesting, actually, is the exiled Austrian novelist Hilde Spiel.

Alan Garner – Where Shall we Run to? A beautiful, brief memoir of growing up in a landscape that’s steeped in history (ancient and family) and in mythology, the landscape that inspired Garner’s novels, from his children’s book The Weirdstone of Brisingamen to his most recent novel, Boneland.

Atul Gawande – Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science. These are essays written whilst Gawande was doing his general surgery residency, focusing on fallibility, mystery and ethics. Honest, inspiring and terrifying.

Heda Margolius Kovaly – Under a Cruel Star. Cruel indeed – Kovaly survived the Łódź ghetto and Auschwitz, and escaped the death march to Belsen, but under the postwar regime in Czechoslovakia, her husband was murdered in one of Stalin’s show trials – the Slansky trial, which mainly targeted Jews, and she, tainted by association with a ‘traitor’, struggled to survive before escaping west in 1968.

Diarmaid MacCulloch – Thomas Cromwell. Homework, if you like, for my reading of The Mirror and the Light. It’s notable how much respect is given here to Mantel’s grasp of the history. It’s a hefty tome, but fascinating. I can’t pretend I was equipped to really appreciate the finer points of Tudor politics, but I got a lot from the book, nonetheless.

Ben MacIntyre – Double Cross. Another extraordinary account of WWII espionage. If this was a novel one might accuse it in places of implausibility – a cast of extraordinary characters and plots of extraordinary audacity, on which millions of lives depended.

Kenan Malik – From Fatwa to Jihad. The updated version of Malik’s 2010 exploration of how the Rushdie affair transformed the debate worldwide on multiculturalism, tolerance and free speech, helped fuel the rise of radical Islam and pointed the way to the horrors of 9/11, 7/7, Charlie Hebdo…

Lucy Mangan – Bookworm. This memoir of a childhood spent reading, voraciously, obsessively, constantly reading, really spoke to me… Mangan is a lot younger, and so some of the books that she devoured were too young for me by the time they came out, but she read everything, so there’s a lot of common ground. Very funny, absolutely delightful.

Eva Noack-Mosse – Last Days of Theresienstadt. Noack-Mosse was deported in early 1945 to the Nazi concentration camp of Theresienstadt. Working in the camp office, she compiled endless lists for the SS, but also her own clandestine statistics and observations. Postwar, this evidence not only helped to reconnect displaced people with their family and friends (or at least to know their fates) but also contributed to war crimes trials.

Marcus O’Dair – Different Every Time. Authorised biography of wonderful musician Robert Wyatt. Affectionate and admiring, but clear-sighted, it’s a fascinating insight into the music and, with it being Wyatt, the politics.

Maggie O’Farrell – I am, I am, I am: Seventeen Brushes with Death. The only writer to crop up in both the fiction and non-fiction sections of this blog. Incredibly tense, these encounters with death are nonetheless about life. O’Farrell was inspired to write it because of her daughter’s severe immune disorder and the experience of facing down death with and vicariously through her daughter.

Pete Paphides – Broken Greek. In a way, this is the musical equivalent of Lucy Mangan’s memoir. It’s the account of a childhood where music – the pop music of the era, as naff as it often was – had overwhelming power and significance. It’s also a story of chip shops, where his Greek-Cypriot parents worked to support their family, and of colliding cultures. It’s very funny, and joyful.

Johnny Pitts – Afropean. I was always going to want to read an exploration of blackness and European identity that starts in my own home town of Sheffield, before heading out to Paris, Amsterdam, Brussels, Lisbon, Moscow… Whether or not Pitts finds his tribe on this quest, as the Guardian puts it, ‘Afropean announces the arrival of an impassioned author able to deftly navigate and illuminate a black world that for many would otherwise have remained unseen’.

Rebecca Solnit – Men Explain Things to Me. A 2014 collection of essays, of which the title essay is the earliest (2008) and is credited with launching the concept of ‘mansplaining’ (not the term, which Solnit doesn’t use or like). Solnit is witty, clear, and absolutely furious. Excellent stuff.

Laura Spinney – Pale Rider. This could hardly be more pertinent – a study of the ‘Spanish’ flu pandemic of 1918-19, how it spread, how it was treated, how different governments responded. Lots of parallels, of course, with our own time. Where we are lucky is that our own pandemic does not follow directly on one of the most destructive wars in history, with populations exhausted, malnourished, displaced. We could have learned a lot, though, if the right people had been interested in learning rather than posturing…

Ron Stallworth – Black Klansman. The story behind Spike Lee’s brilliant BlacKkKlansman, a story which one might have assumed to be a parable rather than reality. Stallworth himself didn’t tell how he infiltrated the KKK until 2006, and this account was only published in 2014. It’s fascinating and astonishing. It’s not just about the Klan, of course, it’s about what it was to be a black cop in the 1970s in the USA.

Under lockdown, I’ve travelled through time and around the globe. I’ve been back to 16th century England, 18th century Ghana, 19th century France and Russia, Nazi Berlin, Iron Curtain Prague. I’ve been to Jamaica, the Andaman Islands, Zimbabwe, Nigeria. I’ve been all over the US – Baltimore and Texas, Maine and Florida, Colorado and South Carolina, New York and Detroit. I’ve been all over my own homeland too. I’ve shared lives and experiences that are close to my own, and others that are so utterly different that I could never have imagined them.

Thanks to all of the writers who’ve opened those doors to me. Whatever else the second half of 2020 brings, there will be more books, more doors into other lives and experiences. I’ll let you know what I find.

Books for the Plague Times

Posted by cathannabel in Literature on March 17, 2020

We’re all experiencing varying degrees of anxiety just now, depending upon our own age and health, or that of the people we love, the people on whom we rely, or who rely on us. We don’t know what’s going to happen, we’re bombarded with information from sources of unknown reliability, and drip-fed information from our government.

What we do know is that all of us are already affected, our lives have already changed. We’re taking precautions that would have seemed silly a couple of weeks ago, and the things we were talking about so intently a couple of weeks ago (Brexit, the football results, holiday plans) are no longer occupying our minds. We’re scared, we’re frustrated, we are in limbo, we are at a loss.

If we find ourselves spending more time at home, as a precaution or through illness, we’ll need more books. Never mind the bog rolls, load up your Kindle or your bookshelves, because whatever the crisis, books are vital. They keep open a window on to the world, they connect us with other places, other times, other people. They inform, challenge, console, inspire, and distract.

This reading list for plague times will focus on consolation, inspiration and distraction. Sifting through my bookshelves I realise how dark much of my reading matter is. Given current world events, and recent personal loss, I feel a hankering for books that can lift me out of the darkness. So I am sharing some of these with you, in case they can lift you too.

I’m not promising that some of these won’t make you cry, if you’re prone to it. I’m not promising that no one dies, or gets diagnosed with a serious illness. I am confident they will leave you feeling cheerier than when you began, or at least having had a break from the grim.

Biography/Autobiography

- Clive James – Unreliable Memoirs. When this first came out, I was working in a bookshop. During the lulls between customers, I started reading it, but had to stop because it made me laugh so much, so uncontrollably. NSFW, to be sure.

- Keith Richard – Life. I never expected to fall for Keith Richards. I read his autobiography because it had had such positive reviews, and obviously because of my interest in the music. But what surprised me is what an engaging writer he is. A lot of it is very funny indeed, and he writes beautifully, perceptively and passionately about music. About the people, particularly Brian Jones and Jagger, he can be harsh (as he often is about himself), but he’s often also generous and gracious. His attitudes to women may be relatively unreconstructed but he clearly likes them, rather than just wanting to have them. Reading about his wilder years, it’s pretty amazing that he’s still here, but I’m glad he hung around at least long enough to write this vivid account of an era and a career that one really couldn’t make up.

- Giles Smith – Lost in Music. John Peel said of this book that ‘if you have ever watched a band play or bought a pop record – if you even know someone who has bought one – you should read this book’.

- Patti Smith – Just Kids/M Train. I love Patti Smith as a musician, but I think even more as a writer. Just Kids, her memoir of life in ’70s New York, and her friendship with Robert Mapplethorpe, is warm, and funny, and touching, and a vivid portrait of the cultural life of the city. In her later memoir, M Train, she talks about life post-Mapplethorpe, life with her husband Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith (ex MC5), and of the losses that marked those years (not just Mapplethorpe, but brother Todd, and Fred). And, unexpectedly, of her obsession with Midsomer Murders. Her warmth and humour permeates every page.

Reading the Detectives

OK, by definition, crime fiction deals in death, often rather nasty death. But in these, what stays with you after reading is not the cruelty or the gore, but the characters, the wit, the dialogue, the humour.

- Ben Aaronovich – the brilliant and bonkers Rivers of London series. They’re a mad mash-up of fantasy and crime and are a delight.

- Dorothy L Sayers (and the Jill Paton Walsh posthumous titles) – Peter Wimsey series. I can re-read the Wimseys any number of times, because the writing, and esp. the dialogue is so glorious. Paton Walsh’s follow-up novels are pitch perfect, so if you want to renew your acquaintance with Peter, Harriet, Bunter and the Dowager Duchess, you’re in luck.

- Arthur Conan Doyle – Sherlock Holmes. More great writing and dry humour, so even when you know from the start how it’s all going to pan out, you can enjoy the ride.

- Elly Griffiths – Ruth Galloway series. Lots of Gothic darkness in the plots but Ruth is drawn with such warmth and humour that we feel we know her as a personal friend and would happily spend a few hours down the pub with her when this crisis is over.

- Lynne Shepherd – Murder at Mansfield Park. Lynne specialises in literary mysteries. They’re pretty dark, but this one is a deliciously subversive take on the Austen.

- Alexander McCall Smith – No 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series. Love the setting, love the premise, love Mma Precious Ramotswe.

Historical Fiction

The further back the better, frankly. One can lose oneself amongst the Plantaganets or the Tudors – not that there are no echoes of our own times (the occasional plague, for example…) but they’re not overwhelming. I haven’t listed the obvious title, the new Hilary Mantel, which is brilliant (I’m halfway through) because you all know about it anyway and are either reading it or about to read it.

- Livi Michael – Wars of the Roses trilogy. Michael tells the story through a number of different voices, of major players and very minor players, mentioned but unnamed in the chronicles. And she threads the accounts in the actual chronicles through her fictional narrative, so we read of the events in the words of writers who lived at that time, and then she takes us into the thoughts and feelings of her protagonists so that they live and breathe for us. I would also highly recommend her earlier adult novels, and her children’s series about Frank the intrepid hamster…

- Rosemary Hawley Jarman – We Speak no Treason. This was a swooningly romantic take on the story of Richard III which I adored as a teenager, but it stands up to a re-read by a more cynical adult. Skillfully as well as passionately written. A cut above the Jean Plaidys (which I devoured at the time, but suspect would find less sustaining now).

- Anya Seton – Katherine. As above. I read lots of others by her but this was my favourite. I also loved Dragonwyck (pure Gothickry), and for a couple of slices of US history, The Winthrop Woman and My Theodosia.

Contemporary Fiction

- Tiffany Murray – Diamond Star Halo rocks. It’s set on a fictionalised version of the residential recording facility at Rockfield Farm, Murray’s childhood home, itself the locus of much rock music mythology. It’s gloriously funny, but has plenty of heart, and the music is part of every line of the text – I could hear the soundtrack in my head, even the music that was imagined and not real. And I often think of protagonist Halo’s night-time prayer, a litany of rock stars gone forever…

- Kate Atkinson – Behind the Scenes at the Museum. Well, reading anything by Atkinson is a joy. Life after Life is one of my favourite books ever but I find it emotionally overwhelming so it’s not a recommendation for now (especially since it has a lot about the 1918/19 Spanish flu pandemic…) This, her debut, is delicious black comedy.

- Anne Tyler – Saint Maybe. Oh, look, just read anything by Anne Tyler. This was my introduction to her work, but I could just as easily suggest Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant, Breathing Lessons, The Accidental Tourist...

- Patrick Gale – Take Nothing with You/Notes on an Exhibition. The most recent Gale, and the first thing I read by him. They don’t shy away from tragedy but the warmth and generosity of the writing always leaves one with a sense of joy and hope. Take Nothing with You talks about music so vividly that somehow I felt I could hear every note as I read.

- Roddy Doyle – Barrytown trilogy (The Commitments, The Van, The Snapper). Also, check out his Two Pints (and its sequel, Two More Pints). All of the entries appeared on Facebook before being gathered together in a book. Doyle ‘used the social network as a home for a series of conversations between two middle-aged men, perched at a bar, analysing the news of the day and attempting to make sense of it.’ Wickedly funny, very rude and sweary, and surreal (check out young Damien’s scientific researches…).

Classics Revisited

There’s a particular comfort to be found in re-reading. You can look forward to favourite bits, brace yourself in advance for the bit that always makes you cry. You don’t have to worry about the plot, because you already know how it all turns out, so you can just savour the pleasures of the writing, the characters, the descriptions, the dialogue. In this category I would put my favourites of the great nineteenth-century novelists: Austen, Dickens, Eliot, Gaskell, the Brontes. A lot of people rate Trollope but I could never quite take to him. And Hardy is a bit bleak for these times.

From the early part of the twentieth century, I’d go for:

- Dodie Smith – I Capture the Castle, in which we meet Cassandra Mortmain (sitting in the kitchen sink) at the age of 17 (‘looks younger, feels older’) – a marvellous mixture of naivety and wisdom. Far older than me when I read it first, so I grew up with her, catching up and then overtaking her (I’m now old enough to be her nan).

- Arnold Bennett – Clayhanger series. A recent discovery (is it a trilogy or a quartet?) I’ve read the first two in either event, and Hilda Lessways is a fantastic character, she blazes off the page.

- John Galsworthy – Forsyte Saga. Family sagas are grand for times when the future is so imponderable, giving one a reassuring sense of continuity. I watched the original dramatisation in the late 60s, with Susan Hampshire & Eric Porter, the one that caused a bit of a kerfuffle because churches found their pews a bit under-occupied on Sunday nights, due to a clash with the BBC1 repeat showing, and some even changed the time of Evensong so their parishioners would not have to face this dilemma. Try telling your kids about the days when most tellies couldn’t get BBC2 and if you missed a programme it stayed missed…

- Daphne du Maurier – impossible to pick just one. But if some are over-familiar, browse through her back catalogue, and try The Glassblowers, The House on the Strand, The Parasites – all much less well known but thoroughly good reads.

- Revisiting one’s childhood reading is often another source of consolation (depending, I suppose, on one’s childhood). I wrote quite a bit about the most significant books of a childhood spent with my head in books in an earlier blog.

Of course, some may interpret ‘books for the plague times’ entirely differently, and I could easily construct an alternative list composed of books about plagues, and other varieties of apocalypse. However, just now there’s quite enough scary in the rolling Coronavirus updates that I don’t need any more. Books to console, inspire and distract, that’s my prescription.

You’ll have your own. And other people have been sharing their lists on social media, which is wonderful. Writer Lissa Evans (@LissaKEvans) has compiled hers (there’s a degree of overlap but lots of titles that are new to me and so lots of riches to explore:

These lists are as individual as their compilers. What brings me joy might leave you cold, and vice versa. But I love sharing the books I love. And if you’re reminded to track down something you read ages ago, or encouraged to read an author you haven’t tried before, I’ll be very happy.

Stay connected. Hang on to your hat, hang on to your hope. Be safe, be well, be kind.

Choices and Chances: International Women’s Day, 2020

Posted by cathannabel in Feminism, Film, History, Literature on March 8, 2020

#IWD2020 #EachforEqual

An equal world is an enabled world. How will you help forge a gender equal world?

Celebrate women’s achievement. Raise awareness against bias. Take action for equality.

A number of things I’ve read or watched just recently have made me ponder the importance of choice in relation to equality. How women across the centuries have been deprived of real choices – and still are.

Re-reading Hilary Mantel’s Bring up the Bodies, in prep for the third volume of her Cromwell trilogy, I thought about the two queens, Katherine and Anne. Powerful women, women with influence, women with resources. And yet – their power, their influence, their resources were entirely dependent upon men: fathers, husbands and, in a different sense, sons. Their fortunes changed on the whim of a man, and there was nothing they could do about it: rejected, humiliated, and in Anne’s case, killed.

Fast forward to the late eighteenth century and the women portrayed in Celine Sciamma’s wonderful new film, Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Héloise is wealthy and privileged. But she has only two choices – the convent or a socially and economically useful marriage. Her elder sister had taken her own life rather than face the latter, and so Héloise must leave the convent and be marketed to potential suitors. There’s a lot to say about this film, about how it doesn’t just subvert the male gaze, it totally obliterates it. We see the women (and there are only a few men on screen, all briefly, all unnamed) through women’s eyes. Heloise seeing herself in the portraits that Marianne paints of her. Marianne’s self-portrait. Marianne surreptitiously glancing at Héloise as she must try to fix her features in mind, in order to paint her without asking her to pose. The two gazing at each other as they realise their mutual desire. Marianne turning, at Heloise’s request, for one last look as she must say goodbye. This is a film I will want to watch and re-watch. (And I was kind of chuffed to read that Sciamma is a huge fan of Wonder Woman – an actual auteur who doesn’t despise it as a superhero blockbuster but recognises its real power and importance.)

Arnold Bennett’s Hilda Lessways is the subject of volume 2 of his Clayhanger trilogy, written in the early years of the twentieth century but set in the 1880s. What’s remarkable is the way in which we are, throughout the novel, in Hilda’s thoughts, seeing everything through her eyes, knowing only what she knows, as she rages against the restrictions of her life, struggles to understand her own emotions, to understand what choices she has, and to face the implications of the choices she has made. She is independent in spirit, she makes her own living for a while (the only female shorthand writer in the Five Towns), but she’s trapped nonetheless. It’s a vivid and moving portrait.

The young woman at the heart of Celine Sciamma’s 2015 film, Girlhood (Bande de filles) rages too. Marieme hasn’t got good enough grades to get to high school so the only option is college for vocational studies. That would mean leaving home though, which her controlling older brother would be unlikely to permit, and which would leave her younger sisters vulnerable. Her attempt to escape her brother’s control simply put her in the power of another man, and her boyfriend offers only a different kind of trap – marriage and babies.

The power in this film lies in its contrasts. We first meet Marieme as she plays American football, an Amazon, powerful in her armour. The girls head for home, all talking at once, laughing and loud and proud. But as they approach home, we see the young men waiting for them, sentinels, and the girls fall silent. We see Marieme taking on the maternal role with her younger sisters, we see her cowed by her brother’s bullying, we see her talking to a young man, all lowered eyes and fleeting glances. Girls together can be joyous (dancing to Rihanna, in shoplifted dresses, looking glamorous just for themselves rather than for a man, high on cheap booze and weed) or threatening (showdowns, mainly verbal but spilling into violence) with other groups of girls, extorting money with threats. These shifts are jarring, troubling. They show us what these young women could be (for good or ill), and what stops them from being what they could be.

So my 2020 heroes are Celine Scammia and Adele Haenel (for Portrait of a Lady on Fire, and for protest at the Césars), Greta Gerwig for making a book that I’ve read dozens of times fresh and powerful.

Elizabeth Warren for persisting. The Doctor, Ada Lovelace, Noor Inayat Khan and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley.

And those we’ve lost: Rosalind Walter (Rosie the Riveter), Heather Couper (probably the first female scientist of whom I was aware), Kathryn Cartwright (blogger, ambassador for the Anthony Nolan Trust), Katherine Johnson (NASA mathematician).

And two young women who could change the world, and who clearly terrify those who really don’t want it to change…

2010-2019 – the best bits… and some of the other bits

Posted by cathannabel in Events, Film, Literature, Music, Personal, Television on December 19, 2019

I honestly hadn’t thought about it being the end of a decade until I saw the first few ‘best of’ lists appearing.

On a personal level, it’s been quite momentous. We both retired, midway through the decade, a decision which we haven’t regretted for a nano-second. I finished my (second) undergrad degree before I left work, and then went straight on to study for a PhD, which I hope to complete early in the next decade. Each of our children graduated twice (four different Universities, three different cities) and found permanent, rewarding employment.

I lost a good friend and colleague to cancer and helped to set up and then chair a charity as his legacy, raising around £30k since 2013 for cancer charities, through a fabulous fundraising event, the 24 Hour Inspire, and other ventures.

I started this blog in January 2012, and whilst I’ve had periods of writer’s block this year it’s given me a way of being creative, having spent most of my life denying that I am or could be. I was also offered the chance to go to the opera for free with a friend, and write reviews of the productions, which has been an absolute delight.

We put lots of things on hold for a while as my mother in law’s dementia worsened, and her care needs became urgent. She died last Christmas. My brother was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2018 and the chemo he’s been on is no longer working. We go into the New Year with heavy hearts.

Politically it’s been a nightmarish decade. The Tories back in power, first in coalition, then in their own right, albeit for a while as a minority government. The EU Referendum and the government’s complete inability to approach the negotiations in good faith and with understanding and intelligence. Obama replaced in the White House by someone so utterly unfit for any kind of high office that I still wonder whether we slipped into some parallel universe at about the halfway point of the decade, after which nothing made any kind of sense.

Should have realised, when I woke one morning in early January 2016 to learn that Bowie had left us. Should have known it was a portent.

So since looking forward is a mug’s game at present, I’ll look back, to the books, films and TV programmes that have sustained me during the last ten years.

Books of the Decade

Some of these titles feature in my already published Books of the Year and Books of the Century lists, as one might expect. I’ll indicate those that do, or that are reviewed in my 60 Books challenge series, so as not to repeat myself too much (and have time to also do the full panoply of decade and year lists that I am somehow compelled to do).

Ben Aaronovitch – Moon over Soho (Books of the Century)

Ferdinand Addis – Rome: The Eternal City was a birthday gift from the Roman branch of our family, following a recent visit to the city, which had made me realise just how fragmented and unreliable my sense of its history was. A hotch-potch of Shakespeare, the New Testament, Robert Graves and Robert Harris, I really needed to get a grip on it all. Addis’s tome is just the thing. It’s very entertainingly written, it takes key events and explains how they came to pass and what followed, and it takes us from Romulus & Remus to Federico Fellini.

Chimamanda Adichie – Americanah. Her Half of a Yellow Sun is one of the top three books of the century (according to me). Adichie’s protagonist here goes off to University in the States, and we follow her struggles to acclimatise and to understand what race means in America, as well as her feelings for her lover back in Lagos. It’s often very funny, and always very sharp and perceptive. The Guardian said that ‘It is ostensibly a love story – the tale of childhood sweethearts at school in Nigeria whose lives take different paths when they seek their fortunes in America and England – but it is also a brilliant dissection of modern attitudes to race, spanning three continents and touching on issues of identity, loss and loneliness.’

Viv Albertine – Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys (Books of the Century)

Naomi Alderman – The Power (Books of the Century)

Lynne Alexander – The Sister illuminates a life lived in the shadows: Alice James was sister to the more famous Henry and William, prevented by ill health and the constraints of Victorian society from expressing her own creativity. Alexander doesn’t hammer this message home simplistically but brings Alice to sympathetic life. ‘A furious volcano of thoughts and desires trapped within a carapace of pain, Alice is a feminist cipher but, more movingly, a beautifully drawn and memorable individual, brave, vulnerable and fiercely intelligent.’ (The Guardian)

Darran Anderson – Imaginary Cities is an exuberant and wildly eclectic tour of cities in Western civilisation drawing on books, films, architecture, myth, visual arts. Totally my cup of tea. Described as ‘an exhaustive, engaging book’ which generates ‘sheer joy for the curious reader’. It certainly did for this curious reader.

Anne Applebaum – Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-56 is a fascinating study of Poland, the GDR and Hungary after the end of the Second World War. The Telegraph said that she takes ‘a dense and complex subject, replete with communist acronyms and impenetrable jargon, and make it not only informative but enjoyable – and even occasionally witty. In that respect alone, it is a true masterpiece’. (Books of the Year)

Kate Atkinson – Life after Life (Books of the Century)

Margaret Atwood – The Testaments is the long-awaited sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale. It does take the action forward – we get to see some of what happened after that book’s final page, but perhaps more significantly, we see Gilead from perspectives other than that of June/Offred, and so we understand more about how Gilead works, and about, in particular the role of the Aunts. It’s completely compelling, and very disturbing. (Books of the Year)

Julian Barnes – The Levels of Life (Books of the Century)

Linda Buckley-Archer – The Many Lives of John Stone. Buckley-Archer began her literary career with the YA Timequake trilogy. This is beautifully written, interweaving a vivid historical narrative with the present day. There’s no time travel, or supernatural/paranormal elements – it just uses a hypothetical genetic characteristic as the basis for the plot. It’s engaging, gripping and ultimately very moving.

James Lee Burke – Robicheaux (Books of the Century)

Jane Casey – Cruel Acts (Books of the Year, and Century)

Jonathan Coe – Middle England. I picked The Rotter’s Club for my books of the century, and this is the third part of that trilogy. This made me laugh a lot. Made me weep a bit. Reminded me of music I love (Hatfield & the North, Vaughan Williams) and of lyrics that always move me: Billy Bragg’s ‘Between the Wars’. (Not mentioned in Coe’s book, but I kept on thinking of the line ‘Sweet moderation, heart of our nation’). It’s rueful and wistful and, I think, hopeful… (Books of the Year)

Suzanne Collins – Mockingjay is the final part of The Hunger Games trilogy. Another series aimed at a young adult readership, this one is pretty dark (not that YA reading should be sugar-coated or cosy, it should challenge and disrupt if it’s doing its job). Vivid and exciting, with a splendid hero in Katniss Everdene, and resists too neat an ending – after so much tragedy and trauma, that would have jarred horribly.

Stevie Davies – Awakening (Books of the Century)

Edmund de Waal – Hare with the Amber Eyes (Books of the Century)

Emma Donoghue – Room (Books of the Century)

Helen Dunmore – Birdcage Walk. Sadly the last novel from Dunmore, who died of cancer in 2018. I picked The Siege as one of my Books of the Century, and read The Betrayal as part of my 60 books challenge – her novels are very varied but always beautifully and powerfully written. The Guardian describes her writing as ‘hazardously human’. It’s particularly poignant to note that the fictional Julia Fawkes ‘lies buried with the inscription “Her words remain our inheritance.” Julia may have disappeared from the record, but Dunmore’s words remain.

Sue Eckstein – Interpreters (Books of the Century)

Reni Eddo-Lodge – Why I’m no longer talking to White People about Race (Books of the Century)

Esi Edugyan – Half-Blood Blues (Books of the Century)

Elif Shafak – Three Daughters of Eve (60 Books)

Lara Feigel – The Bitter Taste of Victory (Books of the Century)

Will Ferguson – 419 (Books of the Century)

Gillian Flynn – Gone Girl (Books of the Century)

Karen Joy Fowler – We are all Completely Beside Ourselves is particularly difficult to write about without revealing a vital twist, so I will avoid any discussion of the plot. Read it anyway, just avoid the reviews (so no link to the Guardian, which called It an ‘achingly funny, deeply serious heart-breaker … a moral comedy to shout from the rooftops’.) (Books of the Year)

Tana French – Broken Harbour (Books of the Year and Century)

Esther Freud – Mr Mac and Me reminded me of Helen Dunmore’s Zennor in Darkness. A writer/artist (D H Lawrence for Dunmore, Charles Rennie Mackintosh for Freud) finds themselves in a rural community at the start of the First World War, and is regarded with suspicion by the locals due to their unconventional behaviour). Mackintosh is seen through the eyes of a fourteen year old boy, intoxicated by the glimpses of a wider world, of art and beauty, that Mackintosh brings.

Jo Furniss – All the Little Children (60 Books)

Robert Galbraith – The Cuckoo’s Calling (Books of the Century)

Patrick Gale – Notes from an Exhibition (Books of the Century)

Alan Garner – Boneland (Books of the Century)

Nicci Gerrard – What Dementia Teaches us about Love (Books of the Century)

Valentina Giambanco – The Gift of Darkness (Books of the Century)

Elizabeth Gilbert – The Signature of all Things. I wouldn’t have expected to enjoy Elizabeth Gilbert’s writing, having a deep-rooted suspicion of the whole Eat, Pray, Love thing. But I really did. Gilbert’s fictional protagonist, Alma Whittaker, is brilliant, lonely, not pretty. She’s a scientist, a naturalist, in the wrong era (she’s born in 1800) to have any chance of fulfilling her ambitions, or her desires. She’s remarkable, utterly believable, her openness and imagination endearing and fascinating. It’s an ambitious novel, that fully succeeds in its ambitions.

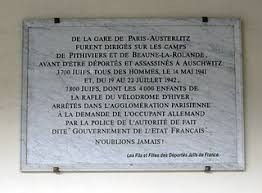

Robert Gildea – Fighters in the Shadows: A New History of the French Resistance. Gildea brings out of the shadows the Resistance that was marginalised for decades – women, Communists, foreigners. It’s much more complicated than the myth that de Gaulle propagated at the Liberation, and more interesting.

Lesley Glaister – The Squeeze (Books of the Century)

David Grann – Killers of the Flower Moon (Books of the Century)

Jarlath Gregory – The Organised Criminal (60 Books)

Elly Griffiths – The Stone Circle (Books of the Year and Century)

Thomas Harding – The House by the Lake (Books of the Year and Century)

Jane Harper – The Lost Man (Books of the Year and Century)

Robert Harris – An Officer and a Spy (Books of the Century)

John Harvey – Darkness, Darkness – the final part of the series of novels featuring Nottingham detective Charlie Resnick.

Noah Hawley – Before the Fall is an excellent thriller, about truth and lies, fame and reality, from the writer of the TV version of Fargo

Emma Healey – Elizabeth is Missing (Books of the Century)

Sarah Helm – If this is a Woman (Books of the Century)

Sarah Hilary – Never be Broken (Books of the Year and Century)

Susan Hill – The Comforts of Home is the most recent (that I’ve read) of the Simon Serrailler series. (Books of the Year. The Various Haunts of Men was one of my Books of the Century).

Christopher Hitchen – Mortality (Books of the Century)

Andrew Michael Hurley – The Loney (Books of the Century)

Jessica Frances Kane – The Report is absolutely fascinating. At the heart of the novel is a little known wartime tragedy, in which no bombs fell, but 173 civilians died. I had never heard about the Bethnal Green disaster when I came across this book, and it set off many trains of thought.

Philip Kerr – Prague Fatale. Kerr’s series of novels featuring Berlin detective Bernie Gunther blend crime fiction with World War II European history. They span from the immediate pre-war period to the long aftermath of the war, and Bernie has been part of it all. He’s a survivor, who’s done bad things and seen worse ones, but somehow retained his humanity, a dry humour, and at least some of his integrity.

Stephen King – The Institute. King’s latest references a number of his previous novels (Firestarter, The Shining, Carrie…) but does something a bit different with these themes. In a way, he’s setting two version of America against each other: the corporate world of the Institute, ‘the cogs and wheels of bureaucratic evil, run by ‘a bunch of middle-management automatons’, against small-town America (the good and the bad thereof). It’s proper cancel all other activities including meals and sleep till the last page King. (Books of the Year)

Otto Dov Kulka – Landscapes of the Metropolis of Death (Books of the Century)

John le Carre – Pigeon Tunnel (60 Books)

Harper Lee – Go Set a Watchman (Books of the Century)

Laura Lipmann – Sunburn (Books of the Year and Century)

Kenan Malik – Quest for a Moral Compass (Books of the Century)

Hilary Mantel – Bring up the Bodies. We’re still eagerly awaiting the third part of Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy. (Wolf Hall was one of my Books of the Century).

Helen Mathers – Patron Saint of Prostitutes is a fascinating biography of Josephine Butler, the remarkable Victorian campaigner who challenged all of the conventions about how a pious and respectable woman should behave by working with prostitutes, and challenging publicly the way in which they were brutalised and abused in the name of public morals.

Jon McGregor – Reservoir 13 (Books of the Century)

Dervla McTiernan – The Ruin (Books of the Century)

Livi Michael – Succession (Books of the Century)

Denise Mina – The Long Drop (Books of the Century)

Wendy Mitchell – Someone I Used to Know is an account by someone diagnosed with early onset dementia. She’s frank and fearless about explaining how the condition affects her as it progresses, but uses her energies to campaign for awareness and understanding, and for practical support. Her blog is funny, sad and enlightening, and it is so rare and refreshing to hear about dementia from someone who is actually experiencing it.

Caitlin Moran – How to be a Woman (Books of the Century)

Sarah Moss – Bodies of Light (Books of the Year and Century)

Thomas Mullen – Darktown (Books of the Century)

Tiffany Murray – Diamond Star Halo rocks. It’s set on a fictionalised version of the residential recording facility at Rockfield Farm, Murray’s childhood home, itself the locus of much rock music mythology. It’s gloriously funny, but has plenty of heart, and the music is part of every line of the text – I could hear the soundtrack in my head, even the music that was imagined and not real. And I often think of protagonist Halo’s night-time prayer, a litany of rock stars gone forever…

Maggie O’Farrell – The Hand that First Held Mine (Books of the Century)

Chinelo Okparanta – Under the Udala Trees movingly explores the Biafran war, sexuality and love across the ethnic and religious divides, class and status in Nigerian society.

David Olusoga – Black and British (Books of the Century)

Philip Pullman – La Belle Sauvage (The Book of Dust, Book 1). I won’t say too much about this as I don’t want to risk giving any spoilers. But it is sheer delight to be back in this world and to re-experience the sheer power, the subtlety, the glorious imagination of Pullman’s writing.

Ian Rankin – In a House of Lies, the most recent Rebus. He’s retired now, and battling with COPD and the lifestyle changes that has forced on him. Does any of that stop him getting involved in the solving of a crime, and getting under the feet of the cops? Have you met Rebus? (Books of the Year)

Danny Rhodes – Fan is about football and football culture, about supporting Nottingham Forest, and, inexorably, about Hillsborough. It’s powerful and harrowing.

Sally Rooney – Normal People (Books of the Year and Century)

Liz Rosenberg – Indigo Hill (Books of the Year and Century)

Donal Ryan – From a Low and Quiet Sea (Books of the Year and Century)

Philippe Sands – East-West Street (Books of the Century)

Noo Saro-wiwa – Looking for Transwonderland (Books of the Century)

Phil Scraton – Hillsborough: The Truth. When Scraton published this 2016 edition of his authoritative, rigorous, and personal account of the disaster, he would not have imagined the news that broke in December 2019, that Duckenfield had been found not guilty. Again, the families who have endured so much – lies, betrayal, vilification, dismissal – for so long, are in pain, and again, it seems no one will be held accountable for 96 entirely avoidable deaths.

Anne Sebba – Les Parisiennes (Books of the Century)

Taiye Selasi – Ghana Must Go (Books of the Century)

Lynn Shepherd – Tom All-Alone’s (Books of the Century)

Anita Shreve – The Stars are Fire was Shreve’s last book. Her protagonist, Grace, has a life that is limited by societal convention and tight family budgets but she thinks it’s fine, mostly, until she loses almost everything, in the terrible fires that swept Maine in 1947. The disaster is described with visceral power and horror, but Shreve is just as interested in its aftermath, as Grace tries to find a way to start again.

Rebecca Skloot – The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (Books of the Century)

Patti Smith – M Train. I picked Just Kids for my Books of the Century, but could just as well have chosen this. With the humour, self-deprecation and warmth that characterised her earlier memoir, she talks about her marriage to Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith, of the series of terrible losses that she experienced, of her music. And, unexpectedly, of her obsession with Midsomer Murders.

Timothy Snyder – Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. I’ve spent a lot of time studying the Occupation of France, and I’m well versed in its horrors. I know better than to minimise the brutality – but the majority of the murders of French citizens and those who were in France during the Occupation took place not on French soil but in what Snyder calls the Bloodlands. ‘Both tyrants identified this luckless strip of Europe as the place where, above all, they must impose their will or see their gigantic visions falter… The figures are so huge and so awful that grief could grow numb. But Snyder, who is a noble writer as well as a great researcher, knows that. He asks us not to think in those round numbers. … The Nazi and Soviet regimes turned people into numbers. “It is for us as humanists to turn the numbers back into people.”

Rebecca Solnit – Hope in the Dark (Books of the Century)

Cath Staincliffe – The Girl in the Green Dress. I was torn when I did the list of books of the century, and chose The Silence between Breaths. So I’m making recompense now. What Staincliffe does so well is to focus not just on the crime (though there is a strong police procedural element to this one, unlike some of her stand-alone novels) but on the ripples created by the crime, on the families of victim and perpetrators, on the police officers themselves. This one will break your heart.

Susie Steiner – Missing, Presumed (Books of the Century)

Adrian Tempany – And the Sun Shines Now (Books of the Century)

Rose Tremain – The Gustav Sonata (Books of the Century)

Elizabeth Wein – Code Name Verity is a brilliant and moving YA novel about young women undercover in Occupied France in WWII. It’s so very cleverly structured – things that don’t seem to quite make sense suddenly become clear in the second half, when the narrator changes. The plot is utterly gripping and the ending made me weep. A lot.

Louise Welsh – A Lovely Way to Burn. This is part 1 of the Plague Times trilogy, a dystopian future where plague wipes out large swathes of the population. We’ve been here, or hereabouts, before of course – Day of the Triffids, The Walking Dead, 28 Days Later, The Stand… Welsh makes it work though, she gives weight to the moral issues as well as giving us suspense, action, horror, and everything we’d expect from the post-apocalypse.

Colson Whitehead – Underground Railroad (Books of the Century)

Jeanette Winterson – Why be Happy when you could be Normal? (Books of the Century)

Farewell to those writers listed above who we lost during the decade: Helen Dunmore, Sue Eckstein, Philip Kerr, Harper Lee and Anita Shreve. Thank you all.

Films of the Decade

I’ve highlighted in bold my favourite films in each of these categories. Many of them I’ve written about already elsewhere, so again I’m not attempting to review or even comment on each one.

Scifi and Superheroes: A brilliant decade both for the superhero genre and – IMHO – Marvel specifically, and for other sci-fi franchises: Star Trek had Beyond, and Star Wars fielded The Last Jedi and Rogue One. My pick from the MCU: Avengers Assemble, Captain America: Civil War, Black Panther, Captain Marvel, Spiderman: Into the Spiderverse, Guardians of the Galaxy I, Thor: Ragnarok. And outside this particular arc, from the X Men, the elegiac Logan. And though I don’t generally do DC, I have to have Wonder Woman.

Best of the bunch: Not dissing Endgame, but Assemble is when I fell in love with Marvel (and with Captain America, TBH). And Black Panther had a significance beyond its place in the Avengers story, and was exhilarating not just for people of colour in the audience, but for anyone who cares about seeing the rich diversity of humanity on screen, as heroes and as villains.

We had Inception and Interstellar, Her and Ex Machina, Looper and Mad Max: Fury Road, The Martian and Gravity, Monsters and Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, A Quiet Place and Source Code.

And the two best SF films of the decade: Annihilation, and Arrival. Visually stunning, intelligent sci-fi. Of the two, Arrival, with its emotionally devastating twist, and its fascinating exploration of language, edges it.

Thrills, Crimes & Heists: Baby Driver and Drive, Bad Times at the El Royale, Skyfall, Gone Girl and Widows. I’m torn on which to pick. With caveats, to do with the film’s failure to meet the low bar of the Bechdel test, I’d pick Baby Driver, which was beautifully described by Empire as: ‘not a film just set to music. But a film meticulously, ambitiously laid over the bones of carefully chosen tracks. It’s as close to a car-chase opera as you’ll ever see on screen.’ Even if the narrative arc (young man in debt to gangster does ‘one last job’ and finds out there’s no such thing) is traditional enough, the choreography, the seamless blend between diegetic and exegetic music, make it entirely original and massively enjoyable.

War: Anthropoid (the assassination of Heydrich), Childhood of a Leader (a more allegorical account of the birth of fascism), Lore (a German teenager in the aftermath of the war). And the best one: Dunkirk – I was overwhelmed, by that intense focus, by the score which built and built the tension until it was almost unbearable (and the use of the Elgar Nimrod as the first of the little ships appeared reduced me, predictably enough, to sobs), and by the non-linear structure which forced one to concentrate, to hold those strands together even as the direction teased them apart.

French films: Michael Haneke’s Amour, Xavier Giannoli’s Marguerite (a French take on the Florence Foster Jenkins story), Olivier Assayas’s Double Vies (Non-Fiction), Mia Hansen-Løve’s L’Avenir (Things to Come), Denis Villeneuve’s Incendies. Varda by Agnes and Bertrand Tavernier’s Journey through French Cinema. My favourites: Celine Sciamma’s Bande de Filles (so much in this movie, but just watch that opening sequence, with the young women leaving hockey match and returning to their homes in the banlieues, and a gorgeous sequence as they dance in shoplifted dresses to Rihanna’s ‘Diamonds’) , Abderrahmane Sissako’s Timbuktu (a stunning Malian film, beautiful and shattering, but with unexpected moments of humour too).

Horror: Cabin in the Woods, What we do in the Shadows. Get Out and Us. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, The Girl with all the Gifts. Under the Skin.

History/Biography: First Man and Hidden Figures, Lincoln, Selma and BlackKKlansman. Love and Mercy (biopic of Brian Wilson).

Comedy: Booksmart and Lady Bird. Death of Stalin and Four Lions. Hunt for the Wilderpeople and Moonrise Kingdom. Sorry to Bother You. World’s End and Submarine. The Muppets, and Paddington.

Animation: Inside Out, Tangled, Toy Story 3.

Adaptations: Macbeth (Fassbender and Cotillard) and Joss Whedon’s Much Ado about Nothing.

Documentaries: I Believe in Miracles (Johnny Owen’s account of the glory years at Nottingham Forest), Night will Fall and They Shall Not Grow Old, Nine Muses, They will have to Kill us First.

Drama: Captain Fantastic and Leave No Trace. Dallas Buyers Club and Pride. Grand Budapest Hotel and The Great Beauty. The Farewell and Short-term 12. Twentieth-century Women and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri. Winter’s Bone and Room. We Need to Talk about Kevin and If Beale Street Could Talk. Life, above all and Cold War.

Music: La la Land

Farewell and thank you to Marvel man Stan Lee, to Emmanuelle Riva (star of Haneke’s Amour, and long before that, of Hiroshima mon amour), to Agnes Varda, and to Michael Bond, creator of Paddington.

TV of the Decade

Subtitled Crime/Thrillers: Dicte, Follow the Money, Greyzone, Rough Justice, Spiral, The Team, Trapped, Wallander, Witnesses, Beck, Before we Die, Blue Eyes, The Bridge, Deutschland 83/86. Plus the bilingual English/Welsh productions, Hidden and Hinterland. Best of the bunch – Spiral (a master-class in French profanity, and a compelling if infuriating bunch of characters, dealing with grim and gritty crime on the streets of Paris.

Brit Crime/Thrillers: Endeavour, The Fall, Foyle’s War, Happy Valley, , Informer, Killing Eve, Kiri, Lewis, Line of Duty, Little Drummer Girl, London Spy, The Lost Honour of Christopher Jenkins, Midsomer Murders, The Missing, No Offence, River, Scott and Bailey, Sherlock, Shetland, Southcliffe, Strike, Suspects, The Suspicions of Mr Whicher, Unforgotten, Vera, Wallander, Bodyguard, Broadchurch, DCI Banks, Black Earth Rising, Ashes to Ashes. Best of the bunch – Endeavour for beautiful, subtle writing for all the lead characters; Killing Eve for deranged, delicious wickedness, Line of Duty for twisty turny plotting, and stunning, forget-to-breathe set pieces in the interview room, Unforgotten for the warmth and humanity of the two leads, the clever subtlety of the writing, and the emotional complexity of cold case investigation.

Other Crime/Thrillers: Fargo, Homeland, Mystery Road, Southland, The Americans. Best of the bunch – Fargo. Bonkers, funny and very very dark.

Sci-fi/Fantasy: Agent Carter, Agents of Shield, The Walking Dead, Doctor Who, The Fades, Utopia, The Handmaid’s Tale, Humans, Misfits, Orphan Black, The Returned, Star Trek: Discovery, True Blood, Being Human. Best of the bunch – Agents of Shield for daring plotting and terrific writing. Doctor Who for bringing us not only Doctors 11, 12 and 13, but the War Doctor and the reappearance of the very first Doctor, River Song and a whole raft of new companions, new and old foes… And Who, as always, through this decade, has given us a hero who thinks, who cares, who values kindness above all things, who isn’t human but somehow reflects back to us the best of humanity. Orphan Black for Tatiana Maslany’s virtuoso performance as most of the key characters. The Returned for a spooky, troubling, atmospheric take on the notion of the revenant.

Comedy: Big Bang Theory, Community, Derry Girls, Doc Martin, Fleabag, The Good Place, How I Met Your Mother, Modern Family, Raised by Wolves, The Thick of It, W1A, Young Sheldon. Best of the bunch – Derry Girls

History/Biography: A Very English Scandal, Brexit: An Uncivil War, Cilla, Gentleman Jack, Mo, Poldark, Resistance, To Walk Invisible, Wolf Hall, Summer of Rockets, World on Fire, War and Peace. A Very English Scandal was a startlingly funny and somehow touching take on a scandal that I recall from my early teenage years (the newspaper coverage at the time was highly educational!). I wrote about Gentleman Jack in my review of the year. And Resistance was a powerful – and historically sound, whilst using the device of a fictional central character who could link to all of the key resistance groups and events – account of Occupied Paris, a subject that I find endlessly fascinating.

Drama: The Casual Vacancy, Desperate Housewives, Doctor Foster, Spin, This is England, Treme, Years and Years. This is England (the TV series) was so powerful that I haven’t rewatched it. It broke me – particularly TiE88. Treme was a joy – it drew its characters with so much love and understanding, that we ended up loving them too. The cast was brilliant, as was the music (it’s the only drama of the decade that has led us to seek out a whole raft of CDs). And Years and Years was timely, moving and let us hope not overly prescient…

Music

This was the decade that I really got into opera. Having the chance to see (and latterly to review) Opera North productions at Leeds Grand Theatre and Town Hall has been not only a delight but an education. I’ve seen productions from across the centuries, and not only has the singing been glorious, but the stagings have been wonderfully inventive. You can find my reviews of the titles in bold elsewhere on this site.

- Cole Porter’s Kiss me Kate

- Purcell’s Dido & Aeneas

- Poulenc’s La Voix humaine

- Puccini’s La Boheme, Gianni Schicchi, Il Tabarro, Suor Angelica, Tosca, Madama Butterfly and Turandot

- Britten’s Death in Venice and Peter Grimes

- Ravel’s L’Enfant et ses sortileges

- Verdi’s Aida and Un ballo in Maschero

- Falla’s La Vida Breva

- Gilbert & Sullivan’s Trial by Jury

- Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti

- Giordano’s Andrea Chenier

- Kevin Puts’s Silent Night

- Handel’s Giulio Cesare

- Martinu’s The Greek Passion

- Strauss’s Salome

- Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman

- Lehar’s The Merry Widow

- Janacek’s Jenufa, Osud and Katya Kabanaova

- Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppeia

- Mozart’s Don Giovanni and The Magic Flute

- Rimsky Korsakov’s The Snow Maiden

- Leoncavallo’s I Pagliacci

- Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana

As always, we have listened to a LOT of music. And over the course of the decade, more and more of it has been jazz. That’s partly thanks to Radio 3, with Jazz Record Requests and J to Z bringing us artists we weren’t familiar with along with lots of stuff from long-term favourites (Monk, Miles, Mingus et al). We’ve seen some live jazz too, from the Kofi-Barnes Aggregation, Arnie Somogyi’s Scenes from the City, and the Stan Tracey Octet.

For several years of this decade, Tramlines was where we went, one weekend a year, for live music. Music in pubs and clubs, in parks, in the art gallery, the Cathedral… It’s changed now, and it’s more a conventional music festival, which doesn’t suit us as well (though it’s a great success and a huge achievement for the city) – what we loved was just wandering around the city centre, from one venue to another, catching bands we’d never heard of as well as a few big names. It was bloody brilliant. And it was where we first saw Songhoy Blues, one of my bands of the decade. These young Malian musicians made me dance, made me smile like an idiot, made me cry a little, when Aliou Toure spoke about his country, his continent, and what the music stood for – peace, love, unity.

We’re privileged in Sheffield too to have Music in the Round – chamber music in the Crucible Studio from the house band, Ensemble 360, and a host of guest musicians. As the name suggests, the audience sits around the performers, so you’re guaranteed a good view, and it gives an intimate feel to the event. I could not begin to list the concerts we’ve attended there. Not just classical either – some of the jazz concerts referred to above were in the Crucible Studio, as was a wonderful gig from the Unthanks.

There have been other venues too – a remarkable performance of Terry Riley’s In C, in the Arts Tower paternoster lifts, and a programme of Reich, Adams, Zorn and others at the Leadmill, from the Ligeti Quartet.

So, another decade bites the dust. These have been some of the best bits. Love and thanks to all of the people who’ve shared these cultural delights with me, to all of the people who’ve created and performed these cultural delights for me, and to all of those who’ve passed on their own enthusiasms to me over the years.

Onwards. Whatever the next decade brings, let’s ensure it’s full of wonderful books, films, TV and music. Let’s hang on to the hope that things can and will get better…

My Life in Books – what I read in 2019

Posted by cathannabel in History, Literature, Politics on December 2, 2019

As you might expect, quite a lot of these titles crop up in my lists of the century and the decade (watch this space), but I’ve read things that fall well outside of those time frames, and things that I very much enjoyed but which didn’t quite make the cut. I haven’t included absolutely everything I read. One or two things were just a bit rubbish, and I’m going to ignore them. What that means is that everything here I enjoyed and/or was glad I had read (not necessarily the same thing), with the occasional caveat, and there are things that I enjoyed a very great deal. I’m not attempting to do a full review for all titles, or I’ll be here till 2021, just a few notes and links here and there, particularly for those titles which I haven’t written about elsewhere or which aren’t going to feature in all of the other (less fun) Books of the Year guides that are beginning to appear. The books that were published in 2019 are in bold, and my favourites have a little star by them, just so’s you know.

Crime, Thrillers, that sort of thing

Ben Aaronovich – The Furthest Station (part of the Rivers of London series, which I love. Moon over Soho is on my Century list)

Megan Abbott – Give me your Hand (a new author to me this year but one who I will follow up.)

Eric Ambler – Journey into Fear (classic thriller from 1940)

Kate Atkinson – Big Sky (new Jackson Brodie!)*

Mark Billingham – Love Like Blood, As Good as Dead, The Bones Beneath, Die of Shame, The Killing Habit (the excellent Tom Thorne series)

Stephen Booth – Fall Down Dead (Cooper & Fry series, set in the Peak District – I’ve read quite a few of these, but not in chronological order, and I keep feeling there’s back story that I’m missing! Will have to fill in the gaps.)

Sam Bourne/aka Jonathan Freedland – To Kill the Truth (follow up to To Kill the President, which was a startlingly close to reality account of Trump’s presidency as well as a nail-biting thriller. This one’s preoccupation is clear from the title – the events described may not be entirely plausible but the basic premiss chills, nonetheless, and Bourne/Freedland knows how to keep his audience gripped.)

James Lee Burke – New Iberia Blues, Robicheaux* (Dave Robicheaux series. Robicheaux is on my Century list)

Jane Casey – Love Lies Bleeding, One in Custody (two Maeve Kerrigan novellas), Cruel Acts* (new Maeve Kerrigan! on my Century list), How to Fall (first in Casey’s YA Jess Tennant series)

Harlan Coben – Tell No One, The Woods

Eva Dolan – Tell no Tales (second in the Zigic & Ferrera series, set in a Hate Crimes Unit)

Louise Doughty – Dance with Me, Honey Dew, Crazy Paving

Tana French – In the Woods, The Likeness, Faithful Place, Broken Harbour* (the first four in the Dublin Murders series – Broken Harbour is on my Century list), The Wych Elm*

Frances Fyfield – Half-Light (I read several of her crime novels back in the ‘80s and ‘90s but nothing more recently. This one is from ’92 and published under her real name, Frances Hegarty, but has reminded me to read anything by her that I’d missed).

Robert Galbraith – Lethal White (the latest Cormoran Strike – The Cuckoo’s Calling is on my Century list)*

Isabelle Grey – Good Girls Don’t Die (another new writer to me this year, and another who I will follow up)

Elly Griffiths – Zig Zag Girl, The Blood Card, Smoke and Mirrors, The Vanishing Box* (the first four in the Brighton Mysteries series, which I love), The Stone Circle* (the latest Ruth Galloway – on my Century list), The Stranger Diaries (first in an intriguing new series)

Jane Harper – Force of Nature, The Lost Man* (the latter is on my Century list)

Sarah Hilary – Never be Broken* (new Marnie Rome! on my Century list)

Susan Hill – Hero, The Comforts of Home* (a novella and the latest in the Simon Serrailler series, on my Decade list)

Doug Johnstone – The Jump, Gone Again

Philip Kerr – The Lady from Zagreb, The One from the Other, Prussian Blue*, Greeks Bearing Gifts (Bernie Gunther series. Sadly Kerr died last year, and so whilst there are a couple of Bernie Gunther novels that I haven’t yet read, that will be that. I’ll miss him. Prague Fatale is on my Decade list.)

John le Carré – Our Game, Absolute Friends (The Constant Gardener is on my Century list, and his memoir Pigeon Tunnel on the Decade list)

Laura Lipmann – Sunburn (on my Century list)*

Attica Locke – Black Water Rising (on my Century list)*

Mary McCluskey – Intrusion

Val McDermid – A Darker Domain (Karen Pirie series – I have read a couple of these now and much prefer them to the Wire in the Blood series, which I just can’t get along with. That puzzled me, given my love for the genre and McDermid’s place in the crime-writing pantheon, so I’m glad to have found these and will follow the series up )

Thomas Mullen – The Lightning Men (sequel to Darktown, which is on my Century list)*

Louise Penny – Still Life (first in the Inspector Garnache series – another series to follow up)*

Ian Rankin – In a House of Lies* (on my Decade list), Rather be the Devil, Hide and Seek, Naming the Dead* (on my Century list) (all Rebus novels)

Cath Staincliffe – Desperate Measures (a Blue Murder novel. Staincliffe’s stand-alone novels The Silence between Breaths and The Girl in the Green Dress are on my Century and Decade lists respectively, and I have thoroughly enjoyed her Sal Kilkenny series too)

Lesley Thomson – Ghost Girl (follow up to The Detective’s Daughter)*

Sarah Vaughan – Anatomy of a Scandal (political/psychological thriller, disturbing and compelling)

Sci-fi/Horror/Dystopian Futures etc

Margaret Atwood – The Testaments (sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, on my Decade list)*

Ted Chiang – Stories of Your Life and Others (includes the short story that inspired the film Arrival, on my Century list)*

Andrew Michael Hurley – Devil’s Day* (his second novel – his debut The Loney was on my Century list)

Stephen King – Elevation, Gwendy’s Button Box, The Institute* (two fairly slight novellas and a stonking new one, which is on my Decade list)

Audrey Nifenegger – Her Fearful Symmetry*(there’s a sequel to her more famous Time Traveller’s Wife in the works, I believe, but this one is also excellent, spooky and moving)

Claire North – 84k* (a gripping and disturbing dystopia, in a society where everything is commodified and human rights have been abolished)

Iain Pears – Arcadia

Philip Pullman – La Belle Sauvage (on my Decade list), The Secret Commonwealth (the first two in his new trilogy)*

Historical Fiction

Marjorie Bowen – Dickon (a 1929 novel about Richard III, from a hugely prolific but largely forgotten author. The Viper of Milan thrilled me to bits as a young teenager)

Sarah Dunant – Sacred Hearts (third in her Renaissance trilogy. It’s set in a convent, and by chance I read it immediately after The Testaments, which set off all sorts of interesting echoes)*

Robert Harris – Imperium, Lustrum, Dictator (the Cicero trilogy, read in preparation for and during a visit to Rome)

Sarah Moss – Bodies of Light (on my Century list)*, Signs for Lost Children, Night Waking*

Elizabeth Strout – Abide with Me

Amor Towles – A Gentleman in Moscow

Sarah Waters – The Paying Guests

Kate Atkinson – Transcription* (WWII/Cold War set novel, about secrets, lies, paranoia, invention. The Guardian described it as ‘an unapologetic novel of ideas, which is also wise, funny and paced like a spy thriller’.)

Other Fiction

André Aciman – Call me by Your Name

Peter Ackroyd – The Great Fire of London

James Baldwin – Giovanni’s Room* (Baldwin’s 1956 novel is a groundbreaking account of bisexuality, with a non-linear timeline. It’s a powerful read – I read quite a lot of Baldwin as a teenager, including the later Another Country, where the themes of race and sexuality are intertwined, as well as his novels exploring the black experience in the US)

Arnold Bennett – Clayhanger (published 1910, first in a trilogy – or possibly a quartet – set in Bennett’s ‘five towns’ in the Potteries, with a very striking female character in Hilda Lessways)

Jonathan Coe – Middle England* (on my Decade list, the follow up to The Rotter’s Club and The Closed Circle)

J M Coetzee – Disgrace (this has been on my bookshelf for many years and for some reason I only got round to it this year. It was excellent, but I don’t know that I want to read more by him, however good and important he is)

Michel Faber – The 199 Steps (read following a short break in Whitby)

Sebastian Faulks – Paris Echo (this should have been right up my street, and I did enjoy a great deal about it. Some critics felt that the history – Occupied Paris – was rather didactically presented rather than being integrated in the narrative. But the stumbling block for me was rather that some of that history was wrong. Careless mistakes that Faulks or someone should have spotted. Does it matter? I think it really does – if you’re going to invoke this (still contentious and disputed) history, get the details right.

Karen Joy Fowler – We are all Completely Beside Ourselves (on my Decade list)*

Barbara Kingsolver – Flight Behaviour

Chris Mullins – The Friends of Harry Perkins (a late sequel to A Very British Coup)

Michael Ondaatje – The English Patient (another one that I hadn’t got round to for years, and that somehow didn’t connect with me. Whether that’s down to me or Ondaatje, I cannot tell…)

Georges Perec – W: Une Memoir d’enfance

Sally Rooney – Normal People (on my Century list)*

Liz Rosenberg – Indigo Hill (on my Century list)*