cathannabel

This user hasn't shared any biographical information

Homepage: https://cathannabel.wordpress.com

2023 on Screen – the second half

Posted in Film, Television on December 15, 2023

I was struck as I compiled this summary of my watching (July-December) by the number of films directed by women, and/or focused on and carried by a central performance by a woman. The Bechdel test isn’t terribly relevant in these cases, and I think that’s a good sign. Women talking to one another about a man doesn’t have to imply a romantic context. To take two very different examples, in Clemency, Alfre Woodard’s character talks primarily to men, about men, but these men are not only her husband but her colleagues and the prisoners on Death Row for whom she is responsible. In Women Talking, the women are talking to each other about men, but about the men who have controlled their lives, kept them uneducated, and raped them, and what they’re really talking about is survival, escape, freedom.

There are some breathtaking performances in the films I’ve seen this year. Alfre Woodard has already been mentioned, but then there’s Danielle Deadwyler in Till, and Lily Gladstone in Killers of the Flower Moon. On TV, seeing women in lead roles is more normalised. Stand-out performances in this year’s TV watching include Regina King in Seven Seconds, Brie Larson in Lessons in Chemistry, Bella Ramsey in Time, and Ruth Wilson in The Woman in the Wall.

I haven’t listed absolutely everything I watched – if it’s the nth season of an ongoing series I haven’t included it unless there was something major and new, and if I really had to rack my brains to think of anything worth saying about it, I have said nothing. I’ve tried to avoid spoilers, but no guarantees.

Top films? Killers of the Flower Moon, The Creator, Paris Memories. And TV – The Lazarus Project, Lessons in Chemistry, Dopesick.

FILM

Barbie (dir. Greta Gerwig)

If anyone had told me a couple of years back that this would be one of my favourite films of the year, I’d have thought they’d lost the plot completely. But of course, this was Greta Gerwig’s Barbie and it was a delight, so packed with visual gags and intertextual references that I really want to watch it all over again, to pick up the details I missed. I laughed out loud, a lot. Several (mainly male) critics have piped up solemnly to tell us not to be so silly as to think it is the most profound meditation, the last word on gender and stereotyping. I’m not sure that those critics really get the relationship that so many women and girls have with Barbie and her ilk – love, hate or a complex mixture of the two, responding to the way she is both aspirational and impossible: she can be dressed as any profession, as a president or a nurse, but she has a body that is physically impossible and that undermines those aspirations.

I never owned a Barbie, but I did have a Sindy (her British cousin), and a Tressy (distinguished by the key in her back which made her hair grow). I kind of liked but never loved them, and was quickly bored with dressing them up, but rather enjoyed getting them to parachute out of my brothers’ bedroom window along with a couple of Action Men (they were all in the French Resistance, as I recall). Which does reinforce the idea that the way a girl will play with a Barbie is not limited or dictated by the marketing. My daughter enjoyed her Barbie dolls in a much more conventional way. But both of us loved the film. I can’t, obviously, speak for all women, but like us, most women I know just revelled in its wit, its playfulness, and its mild subversiveness, laughed a lot and had a really good time (sorry guys).

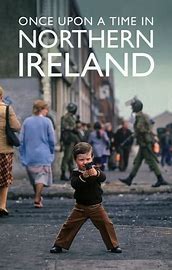

Belfast

This is a love letter of a film. And its warmth and humour, its mixture of the prosaic everyday and explosive violence make it both charming and genuinely frightening and tense. It’s not without its sentimental moments, but (as with Spielberg’s The Fabelmans) I felt inclined to forgive the elements of self-indulgence, when the film is as beautiful and moving as this.

Best of Enemies

Not to be confused with Best of Enemies, the NT on Screen production based on Gore Vidal and William Buckley’s TV debates during the primaries in 1968, this one is based on the meetings set up in North Carolina to try to resolve issues about the education of black children, in which KKK leader C P Ellis (Sam Rockwell) faced off against local activist Ann Atwater (Taraji P Henson). I would have liked to know a lot more about Bill Riddick who initiated this format of collective problem solving. And I did wonder about the degree to which Ellis was humanised – not that I’m doubting his change of heart, for which there is undeniable evidence, but the film perhaps sentimentalised it a little bit, made it seem easier than it must have been, and glossed over his history somewhat. Atwater is more one-dimensional than Ellis, despite an excellent performance from Henson, because she’s given less chance to show dimensions other than righteous anger.

Brooklyn

Lovely, funny and moving. Saoirse Ronan is at her most luminous here, and from the start she has our hearts, so that some of us (me) were talking to her, telling her not to be daft, imploring her not to make the wrong choice.

Captain Phillips

Even though we know the outcome, this is super tense. And Hanks does his stoic, ordinary man in an extraordinary situation exceptionally well, with Barkhad Abdi as a compellingly charismatic opponent. Hanks lets us see behind the stoicism in the final stages of the film when his terror and trauma are powerfully portrayed.

Clemency (dir. Chinonye Chukwu)

This is bleak. A prison governor (Alfre Woodard) has to oversee executions of prisoners on death row, and it takes a toll on her mental health and her marriage. The film explores the interaction with one prisoner, who’s always declared his innocence, as his appeals run out of time. Woodard is just extraordinary – there’s a stillness to her which has nothing to do with calm, everything to do with someone holding on desperately to self-control.

The Creator

Visually fantastic, thrilling and moving, this treatment of AI goes somewhat against the current grain, which takes us to places we don’t expect. The Guardian described it as ‘ambitious, ideas-driven, expectation-subverting, man-versus-machines showdown, … one of the finest original science-fiction films of recent years’.

Detroit (dir. Kathryn Bigelow)

1967, riots in Detroit, the Algiers motel incident. It’s history, but the theme of police treatment of black suspects/bystanders is horribly present-day. It’s extraordinarily tense, and that tension keeps on building.

Empire of Light

This had very mixed reviews, but I watched anyway, and I liked so many things about it. Olivia Colman, for one (she’s always a reason to give something a go, at least, and she is outstanding in this). One of the more sympathetic reviews described it as ‘sweet, heartfelt, humane’, which I think is about right, and notes that it’s not afraid to be brutal and very dark when the story requires that.

The Favourite

Colman again, proving her remarkable virtuosity and versatility. Here she’s the borderline bonkers Queen Anne, with Rachel Weisz and Emma Stone as the two women jostling for her capricious favours.

Inside Man

A Spike Lee heist movie, with a starry cast including Washington, Ejiofor, and Jodie Foster. The plot twists and turns like a very twisty thing.

Judas and the Black Messiah

The murder of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, brilliantly portrayed by Daniel Kaluuya who oozes charisma, with Lakeith Stanfield as the titular Judas, oozing unease. It’s thrilling, but also subtle and perceptive.

Killers of the Flower Moon

I read the book (by David Grann) a couple of years back and thought at the time that it would make a great film. Here is that great film. Superb performances from de Niro, di Caprio and, most particularly, Lily Gladstone as Molly, the beating heart of the film. It’s long, and perhaps could have been tightened up a bit at the mid-point, when one starts to wonder when the proto-FBI guy is going to show up. But on the other hand, that’s the point in the film when Molly moves to the centre of things (even when she’s off screen). There’s an intriguing final sequence when, rather than scrolling text telling us what happened to the protagonists we get a view of the studio where a radio programme is being recorded, part of a series on the history of the FBI. It raises all sorts of questions – the transformation of these horrifying events into public entertainment (Scorsese challenging himself there), and the voicing of the Osage protagonists by white folks.

Leave the World Behind

Adapted from the book by Rumaan Alam, which I read a year or so ago, this is very well done, with great work from Julia Roberts, playing a truly unpleasant human being, Ethan Hawke and Mahershala Ali in the lead roles. It builds the unease skilfully, with some brilliantly strange scenes (I particularly liked the Teslas) as the protagonists bicker and speculate, and then it leaves the protagonists, and us, in mid-air as it were, still not knowing for sure what is happening, and not knowing at all what will happen next, how/whether they can survive.

Living

When I saw the trailer for this, I said that I would wait for it to come on to TV because I feared it would be the kind of film that would trigger embarrassingly loud sobbing. I wasn’t wrong, but it took until the final sequence for ‘something in my eye’ to give way to floods of tears. The story is very British, very understated, and Nighy is perfect, as is Aimee Lou Wood. It all comes together very movingly, with a soundtrack that was guaranteed to floor me.

Marshall

Good, solid legal drama based on the career of Thurgood Marshall (Chadwick Boseman). It works as a generic courtroom drama, but with the context that the accused is a black man, charged with the rape of a white woman, and that his lawyer is black, working with a white Jewish man, in 1941, which gives it whole other layers of tension. It also reminds me how good Boseman was, and how sad a loss.

The Marvels (dir. Nia da Costa)

Hugely enjoyable, often funny, with the delight of seeing the three Marvels working together (and swapping places unpredictably). Iman Vellani, Kamila Khan aka Ms Marvel, is a tremendous source of energy and enthusiasm, bubbling and babbling in her hero worship of Captain M (‘Captain, my Captain’, as she puts it), and trying to find the right ‘made-up name’ (as one Peter Parker put it) for Captain Monica. If I had to find fault it would be that we just don’t get enough of the back story to feel the weight of Captain Marvel’s guilt and remorse, why she is called ‘The Annihilator’, and why Zawe Ashton’s Dar-Benn is raging across the universe to (as she sees it) right the wrong that was done to her people. It’s too lightly sketched in. And the significance of the rather delightful planet of Aladna, where the Captain briefly swaps her superhero combat gear for a princess dress, and where everyone sings rather than speaking, is also touched on lightly, and we don’t return there to see the consequences after the Krill steal their oceans (or some thereof). The film tries to do too much, particularly given the comparatively short running time. But we can meanwhile enjoy the Marvels, enjoy Goose and his/her progeny providing a novel solution to an escape pod problem, enjoy Kamila Khan’s parents rising to the occasion with remarkable sang froid, and in all honesty to simply enjoy the fact that this is all really, really, annoying the toxic man-boys who feel threatened by these glorious, powerful, funny, and beautiful women.

The Mitchells vs the Machines

Brilliant, animated AI themed sci-fi with masses of heart and humour. (And Olivia Colman.)

Northern Soul (dir. Elaine Constantine)

A slice of social realism, kind of old-fashioned, I suppose, in charting teenage rebellion, musical epiphany, and descent into violence and addiction. But the music! Northern Soul was the soundtrack of last summer, unexpectedly, thanks to the Northern Soul Prom, which set me off binging those glorious, exhilarating tunes. And that lifted the drama, which beautifully conveyed the oddity of these rare slices of US soul taking such hold on the lives of young working-class northern lads and lasses.

Oppenheimer

Another blooming long film (though I can’t say I was conscious of how much time was passing whilst I was watching). We watched at the IMax, being as Nolan apparently said he’d created it for that, but unlike Dunkirk, where the size of the screen enhanced the immersiveness of the soundtrack and the tension of the drama, here it is only sporadically relevant, given that long sections of the movie are set in committee rooms and court rooms, with a lot of men talking. No matter. It’s an excellent drama, Cillian Murphy is superb, as is Robert Downey Jr. Emily Blunt and Florence Pugh are great, but somewhat under-used. Oddly, the three great Jewish scientists at the heart of the drama (Einstein, Oppenheimer, and Heisenberg) are all played by non-Jews (Conti, Murphy and Branagh respectively), which begs some questions – does it matter? If it does, what do we do about it? Did the casting raise any questions for Nolan, or was it just not thought about?

I followed up the movie with a re-watch of the 1980s drama with Sam Waterston in the lead role (very good, though slow-moving and some of the American accents sounded a bit shonky to me), and a documentary about Oppenheimer’s trial.

Paris Memories (dir. Alice Winocour)

A young woman caught up in the 2015 Paris attacks (see also the documentary on those attacks, below) tries to process her memories (or lack thereof) and the trauma she suffered, physically and mentally. It’s excellent, and takes us to some unexpected places, exploring the impact of those events on the ‘sans papiers’ who worked in the bistros that came under attack. Very moving.

The Post

Excellent, solid Spielberg drama about the Washington Post’s publication of the Pentagon papers. Kind of a prequel to All the President’s Men. Hanks and Streep are predictably great.

The Remains of the Day

Another one that I really should have seen ages ago, and don’t know why I never had. I read the book, I love Kazuo Ishiguro’s work, I’m fascinated by that period just before the war and the history of appeasement, I love Emma Thompson… Anyway, I have now watched the film and it’s every bit as good as everyone says. The sense of repression of emotion, of engagement, is so strong, especially in Anthony Hopkins’ performance, it’s almost infectious.

Rustin

The film foregrounds Bayard Rustin’s role in organising the 1963 March on Washington – he has been left in the shadows compared with some of the other black leaders involved, and it’s clear why. He was gay, and didn’t pretend otherwise, which made him a target for the FBI, but also made other leaders, particularly those most strongly linked to the church, uneasy with him. It’s not a perfect film, a little bit predictable and ‘worthy’, but Colman Domingo is tremendous as Rustin (and Aml Ameen is great as MLK too, an understated and subtle performance), and it’s good to see Rustin taking the place in the spotlight that he so clearly deserved.

Sapphire

Something of a curio – a British crime film from 1959, in which the victim is a young black woman who’s been passing for white. The film takes us into black London nightlife of the time, and explores racism through of the prejudices of both the junior policeman investigating the murder, and the family of the victim’s fiancé. Features Earl Cameron, one of the first black actors to take a lead role in British films. It’s dated, of course, but bloody good for its time, and fascinating.

The Sense of an Ending

Adaptation of Julian Barnes’ novel, which I read and about which I was ambivalent (as I have been about other Barnes). But whereas the book did deliver a punch to the gut, a real sense of shock and tragedy, the film is just too polite. It’s all very well done, and one can’t fault the performances (Broadbent, Walter, Rampling in the leads), but it felt somewhat distant, detached, reserved.

The Silence of the Lambs

I’d never seen this. No idea why – I’d read the book many years ago, and there must have been opportunities to see it on TV many times since then. No matter, it was excellent, desperately tense and Hopkins and Foster were both superb. That final sequence with Foster being stalked in the dark is terrifying and horrible to watch, not least because for some of it, we’re seeing things from the killer’s point of view. One gets that less today, perhaps, which is a good thing…

Silver Dollar Road

Brilliant documentary from Raoul Peck (director of I am Not Your Negro) about a black family in North Carolina, who find their ownership of property which had been in the family’s hands for generations is challenged, and that the weight of white society is now pressing them to give up their homes (two of them were imprisoned for eight years for trespassing by not moving out of their houses). It’s depressing, but the resilience and determination of the family is very moving.

Testament of Youth

It was inevitable that I would compare this to the BBC version broadcast in 1979, which I adored. And in many ways, it stands up very well. But whilst Alicia Vikander smoulders beautifully, Cheryl Campbell blazed, and the film somehow is more polite than the TV series, even if it is unflinching in the scenes in the field hospitals, the mud and the blood and the agony. It’s visually great, including one very striking scene when Vera rounds a corner to see a field of stretchers, each bearing a seriously injured (or already dead) soldier – surely a nod to the panning shot in Gone with the Wind of the square in Atlanta filled with stretchers, but which also reminded some reviewers of the scene in Oh What a Lovely War, with the white crosses on the hillside.

There will be Blood

Daniel Day-Lewis goes over the top (way, way over) in this gripping, unhinged tale of greed and ruthless capitalist exploitation.

Till (dir. Chinonye Chukwu)

The story of the murder of Emmett Till and his mother’s battle for some kind of justice. Danielle Deadwyler is exceptional. It’s a shattering, brutal story and it unfolds with a terrible inevitability, not just because we know the outcome in this particular case but because ‘sassy black kid goes South’ at that time was never, ever going to end well. Some reviewers questioned whether we need to keep telling these stories. I think we do – I knew of Emmett Till since I was a teenager reading about the Civil Rights movement, but that doesn’t mean everyone knows. And we know all too well that progress, however hard won, can be wound back. In any case, if we’re going to tell these stories, this is the way to do it.

True History of the Kelly Gang

Excellent adaptation of Peter Carey’s book, with George Mackay (Pride, 1917) as Ned Kelly. It’s a strange, violent tale, and there are no real heroes, but it’s compelling and complicated, and if we can’t share Kelly’s distorted view of reality, we can feel pity and sorrow for his life, and his death.

Women Talking (dir. Sarah Polley)

Based on Miriam Toewes’ book, which in turn is based on the series of druggings and rapes carried out in the Mennonite settlement in Manitoba Colony, Bolivia in 2005-09. There are some powerful performances here – Claire Foy, Jessie Buckley, Frances McDormand, amongst others, and Ben Whishaw as the only man allowed to witness the women’s debates about what they are going to do, having exposed at least some of the perpetrators. It has such obvious wider resonance in its exploration of the choices they face – do you fight back, do you leave, do you forgive, and what is the cost of each of those responses? – heightened by the fact that these women have been kept uneducated and dependent, and taught that they must obey their men.

TV

Ahsoka

I’m not fully immersed in Star Wars lore, so I had to concentrate to remind myself where we were in the chronology and who some of the people were. But it’s a cracking narrative, and great to have so much of it carried by female characters (on both sides).

Annika

The central character is given a fair few quirks, which Nicola Walker carries off well (breaking the fourth wall, and going off on all sorts of literary/mythological tangents) and some back story which only emerges gradually. The actual crime side of it is handled well, with enough humour to avoid melodrama but without trivialising the deaths and their implications.

Bali 2002

The terrorist attacks on Bali from the point of view of some of the survivors, and of the investigators (Australian and Indonesian) working together to try to track down the perpetrators. Powerfully done, and whilst the survivors are British or Australian, we also see these events from the perspective of a young Indonesian woman whose husband is killed in the bombing.

Becoming Elizabeth

A series cut brutally short. We follow Elizabeth’s precarious life between the death of Henry VIII and the expected death of Edward VI, but apparently there will be no second season to take her through the reign of her sister Mary. That’s a shame, because as historical dramas go, this was excellent, pretty accurate, not too burdened with period-speak, and with a properly feisty performance from Alicia von Rittburg, as well as the always excellent Romola Garai as the much more tightly wound Mary.

Best Interests

This was agonising (see also There She Goes, although that had more of a leavening of humour, albeit quite dark). A family struggling with the awful decision of whether to withhold medical treatment from a child who, the medics say, is beyond benefiting from it. This is a situation we know from court cases and frenzied tabloid coverage, given depth and humanity. Martin Sheen and Sharon Horgan are excellent, torn emotionally by the horror of the dilemma, and torn apart from each other too.

Black Mirror

A mixed bag – Joan is Awful, Beyond the Sea and Demon 79 were excellent. The others, I thought, were enjoyable but a bit more predictable.

Bodies

Timey wimey crime, with Stephen Graham in the lead role. Excellent stuff – one could quibble or question some of the plot details, but no one in the history of timey wimey drama has ever done anything that couldn’t be quibbled or queried, so I can live with that. It had me completely gripped, and often unexpectedly moved.

Crime

A pretty generic crime drama that thinks it is more than that. So melodramatic that at times it almost seemed comical. There is a second series, but life’s too short for this, I’m afraid.

The Crown

This final series has attracted a lot of hate. I think the problem is that, whereas with the earlier series, we were seeing world events from an unfamiliar perspective and getting a (speculative and fictionalised) view of royal life that we hadn’t glimpsed before. Now what we see on screen is what we already know, what we have seen in other dramas (the reaction to Diana’s death notably in The Queen, by the same writer) and in the papers. It’s not, I think, bad, just lacking in freshness and surprise. I could have done without the spectral reappearances of Di and Dodi though – that was just silly.

Doctor Who

I finished my re-watch of all post-gap Who just in time for the 60th anniversary specials, and Ncuti Gatwa’s arrival on Xmas Day. Of the three specials, the first was a delight primarily because of the reunion of Doc and Donna, and the resolution of the way they had previously parted. The story was fine, but the second episode really took off. It was just Doc and Donna here, and it was absolutely nail biting stuff about which I will say nothing further. In the third, Neil Patrick Harris had an absolute blast as the Celestial Toymaker, and we were introduced to Ncuti Gatwa’s Doc, who was as charismatic, charming and funny as I knew (from Sex Ed) that he could be, and I can’t wait for Xmas Day to see him properly inhabiting the role.

Fellow Travellers/Good Night and Good Luck

I’ve put these together because they cover the same era and some of the same events, the McCarthy witchhunts. Good Night is based on the career of Ed Murrow (played by David Strathairn), whose catchphrase gives the film its title, and his attempt to navigate the dangerous waters of McCarthy generated paranoia whilst retaining his integrity. It’s powerful and moving. Fellow Travellers extends the drama over another couple of decades, and its focus is on the ‘lavender panic’ generated again by McCarthy. This led to the denunciation and arrest of many gay men and women and many others having to bolt and barricade the closet door, and make marriages of convenience to protect themselves. The main protagonist is no hero – a bit of a bastard really – but Matt Bomer gives him depth and nuance. Jonathan Bailey and Jellani Alladin are also excellent as the McCarthy staffer and the black journalist trying to survive in this hostile climate.

Good Omens

Huge fun, with Sheen and Tennant playing delightfully off each other as angel and demon respectively. Very funny but at times with a real sense of peril, and the finale of season 2 suddenly rendered me all emotional. Hope there’s more of this to come.

I Claudius

I remember this series so vividly from 1976. And I remember the title sequence, which I still can’t watch (I even remembered the point in the title music when it’s safe to open my eyes because the snake is gone). It wears very well indeed, with the sole exception of the ageing make-up, which looks pretty ropy when watching in HD. But the performances are fantastic, and it revels in the decadence and ruthlessness of Livia, Caligula, and the rest (including Patrick Stewart, with hair, as Sejanus).

The Lazarus Project

Excellent, complex time travel drama from the writer who gave us Giri/Haji a couple of years back. There’s plenty of action, a stratospheric body count (multiple versions of people get killed multiple times), and a willingness to embrace moral ambiguity which could leave one not rooting for anyone, but (for me) made me feel for the characters even more. There’s plenty to explore in a third series and I hope there will be one, especially since we were denied a second for Giri/Haji.

Lessons in Chemistry

I thoroughly enjoyed the book and the series, although in slightly different ways. That’s partly because it cuts back on the whimsicality of the dog expressing its thoughts on events – that aspect of the book, whilst charming in small doses, would not have worked on screen, I don’t think. The biggest change though is the complete transformation of Elizabeth’s neighbour Harriet, from an older woman, victim of domestic violence, to a woman who is in a way a mirror image of Elizabeth (young children, absent husband, ambitious in her own profession) but black. Whilst I didn’t when reading the book think about this, having the context of the civil rights movement to offset Elizabeth’s battles for women’s independence adds depth to what could otherwise be a somewhat feel-good account. It’s a risky move though. The book’s Harriet represents an individual trauma which connects potentially to all women. The TV Harriet represents the African American struggle against segregation in its overt and more underhanded forms (running the new freeway through a predominantly black residential area, for example). To do justice to that, and to adequately explore this, and Elizabeth and Calvin’s responses, needs more time than could be spared from Elizabeth and her daughter’s own stories. And I think this was apparent in the ending, which rather glossed over the outcome of the freeway campaign. But I loved so much about this, and Brie Larson was wonderful.

Loki

This latest series is overshadowed by the Majors/Kang problem. Having built He Who Remains into the whole narrative structure of the next phase of the MCU, Marvel now has to deal with Jonathan Majors as the subject of some very nasty assault charges. Do they write Kang out? Recast the role (not as problematic from an audience point of view as it might seem, given that we’ve seen multiple variants of Loki in this series)? Either would be better than continuing as they are when we don’t know what might emerge at any point, how his ‘legal problems’ might be resolved, or what impact he might have on cast and crew. If one can put that aside, however, this was a great series, and Tom Hiddleston conveyed Loki’s new-found sense of purpose without losing his spark or his humour. The interaction between him and Owen Wilson’s Mobius (when Mobius remembers who Loki is) is also a joy. We await with interest what happens next, given how we left Loki in the final scene…

The Long Shadow

This dramatization of the years when Peter Sutcliffe attacked and murdered women across Yorkshire is different from the others in that we don’t see him until very late in the drama. We don’t see any attacks either, it isn’t gory or ghoulish or salacious. What we do see is the women (a few of them, at least), as actual human beings, with actual lives, with hopes and fears and feelings. That changes things dramatically. We also see the investigation, but alongside the men (not all of whom are sexist bigots though too many of course are) we also see some of the young policewomen who worked the case and a glimpse of the impact on their lives. I thought it was excellent, with one caveat. I understand why a few characters were created for ‘dramatic purposes’, allowing us insights that we would not have had otherwise, so the invention of a young prostitute, forced back out on the streets even after someone she knew had been murdered, because she was supporting a young child, was fine. Until she herself became one of Sutcliffe’s victims, and thus displaced in that grim roll call one of his actual victims. That didn’t feel right, not at all.

The Miracle

Bonkers Italian series. A statue of the Virgin Mary, weeping blood, is found alongside the body of a crime boss, and a highly confidential investigation starts to try to work out how, why, etc. It is begging for a second series – we were left with so many questions (some but not all were just WTF??) but there’s nothing so far, and this was first broadcast in 2019. It’s compelling, bizarre, beautiful.

Mr Mercedes

An excellent Stephen King adaptation! King’s trilogy of crime novels (there are other linked novels, including his most recent, Holly) with Brendan Gleeson as retired cop Bill Hodges. There are great performances all round, and the series creates exactly the mood of unease ramping up to full on horror that is King’s speciality. It’s way too dark and disturbing to binge but it’s absolutely compelling.

One Night

A past trauma coming to light decades on, and disrupting the lives that the protagonists have built, is not exactly unexplored territory. But this is extremely well done, and doesn’t go where one might expect. Fine performances from Jodie Whitaker (see also Time), Nicole da Silva and Yael Stone. As is so often the case, the complexity builds up over five (or however many) episodes and then the final instalment feels a bit rushed, but overall it was excellent.

Painkiller/Dopesick/Pain Hustlers/Crime of the Century

I’d been aware in general terms of the opioid crisis (not least through Barbara Kingsolver’s brilliant Demon Copperhead) but hadn’t know to what extent this was created cynically and criminally by the Sackler pharma empire. Three dramas and a documentary have filled in the gaps in my knowledge. Of the dramas, Dopesick is the strongest, but Painkiller is very similar (albeit with a more confusing structure), both moving between the small communities where industrial injuries were treated with Oxycontin, which was pressed on to the local doctors with outright bribery and lies, resulting in hopeless addiction, the Sackler organisation egging its salespeople on to sell more and more pills, and the lawyers looking for ways to stop them. It’s an absolutely horrifying story, hard to believe, but the documentary makes it clear that the dramas are not overstating this at all.

Partygate

More horrifying true crime. Interweaving the stories of individuals under lockdown, separated from the people they love, trying to do the right thing, dying alone, with the Downing Street crew, with their contemptuous treatment not only of all of us who were following the rules that they solemnly propagated, but the cleaning staff who had to sort out the carnage after their endless parties. Time for this lot to be cleared out, I think.

Poker Face

Natasha Lyonne as a woman who can tell a lie when she hears it, finds herself mixed up in organised crime and on the run. It’s pretty formulaic – she rocks up in a new place, there’s a murder, she figures it all out with her inbuilt lie detector and moves on, just ahead of her pursuers. That this doesn’t get old fast is down to Lyonne’s charisma, and the humour of the script.

The Reckoning/ Russell Brand: In Plain Sight/National Treasure

A rather queasy selection of programmes on a common theme. National Treasure is fictional, starring Robbie Coltrane as the eponymous treasure, who finds himself accused of a historic rape. It’s a tough watch, with an ambiguous ending. But not as tough a watch as the documentary on the accusations against Russell Brand, which was horrifying and nauseating. I had disliked Brand from the first time I saw him on TV, without being quite sure why, and nothing I’ve seen, in the programme or in the responses to it, makes me less hostile. Jimmy Savile, brilliantly portrayed by Steve Coogan, is perhaps more completely monstrous than Brand, if there’s any point in attempting to quantify monstrosity. As he’s dead, the programme wasn’t held back by fear of litigation, and it pulled no punches. I can’t claim prescience in Savile’s case – I thought he was irritating and weird, rather than sensing anything more sinister, but Coogan showed very cleverly and chillingly the switch from the jolly, avuncular public presentation to the callous abuser behind closed doors. Should this programme have been made? Had it not included the voices and faces of some of his victims, I’d say not. But they underpinned everything that the drama showed, and as they had been silenced for so long, this seems right and proper.

The Secret Invasion

Why was this so disappointing? I had high hopes at first, given the cast, but somehow it all went a bit meh. It isn’t down to the performances, and the central idea is great, but it needed more context, more development, more time, to build more gradually and create more depth.

Seven Seconds

Lord, this was heavy. Rightly so, given the plot (a cop accidentally kills a young black kid and a cover-up is launched). Regina King is magnificent as the boy’s mother. My caveats are that to add into an already potent mix a bunch of personal issues for the lawyer and homicide detective who are trying to get justice for the kid is all a bit clichéd, and that it ends up being a bit clunky and predictable, so that every time our guys seem to have made a breakthrough you just know that it’s going to all fall apart.

Sex Education

The final series. OK, I think it did give in to a bit more preachiness at some points, and what had seemed effortless in earlier seasons seemed more laboured, at times. The other problem is that this season’s new cast members – and there were quite a few of them – didn’t have time to really wriggle their way into our hearts as the original core cast members had. But overall, it drew the individual stories of at least some of those original cast members to a resolution in ways which respected their individual characters and their growth over the previous three series. And I was glad it didn’t do that by coupling them all up or tying up all loose ends in other overly tidy ways. It’s been a warm, funny, startlingly graphic, sometimes ridiculous but always life-affirming ride.

Silo

It’s a mark of confidence (or Jed Mercurio’s influence?) that this series could open with David Oyelowo and Rashida Jones in lead roles and then dispose of them both quite quickly (and they weren’t the last – the body count in this is pretty high). I found the pace mid-series lagged a little, it felt as though we weren’t learning much more about the silo, but then it really picked up and we hurtled to the final cliffhanger. I look forward to series 2.

The Sixth Commandment

True crime series always leave me with some mixed feelings – the necessary conflation of real and invented characters, the messing with chronology, the speculative elements. That this worked as well as it did was not down to the police procedural side of the story, but to the focus on, and the portrayal of the two victims. Both showed their vulnerability without compromising their dignity – perhaps at this stage of my life I can imagine more easily how one might be so deeply lonely that one might become prey to a manipulative conman. Timothy Spall in particular turned in an absolutely devastating, heartbreaking performance, as a man who didn’t believe he was worthy of love, and who thus took what it seemed he was being offered with gratitude and joy. As with The Long Shadow we focus on these victims, whilst the perpetrator and his accomplice remain blanks.

Strange New Worlds

This Star Trek series goes from strength to strength. It has the confidence to be funnier and more inventive than, say, Discovery (I always wanted to love Discovery more than I actually did). In this season, we’ve had a classic time travel episode, which turned out to have more emotional depth (and ongoing implications for one of the lead characters) than one might have anticipated, a cross-over with Lower Decks (an animated series) and, joy of joys, a musical episode. Like its obvious (someone actually says, ‘I have a theory’, and there is a gratuitous mention of bunnies) inspiration, Once More with Feeling (from Buffy season 6, as if you didn’t already know that), it uses the device of a compulsion to sing to force revelations from characters who have been trying to hide things from each other – here it is triggered by science rather than by a demon, of course. It is very funny (the Klingons in slightly bhangra-tinged boy band mode are a delight) and it works to move the overall narrative along.

Then You Run

I think this series has a higher body count than anything else I watched this half-year, with the possible exception of The Lazarus Project… It’s also often funny, very tense and thrilling, and often doesn’t go where you expect it to. With great performances from the quartet of young women whose post-A-level excursion to Rotterdam goes rather off-piste, including Vivien Oparah, the lead in the wonderful Rye Lane.

There She Goes

As with Best Interests, this digs deep into parenting pain which I have never had to experience. Here it is the discovery that the child has a chromosomal deficiency which means she has severe learning disabilities and autism, manifesting in extremely challenging behaviour. The series explores the tensions between the parents in trying to live with Rosie, as she grows up and the difficulties they face only change, never diminish. Excellent performances from David Tennant and Jessica Hynes.

Three Little Birds

Lenny Henry’s dramatic retelling of family stories from the 50s is a mixed bag. It pulls no punches in its portrayal of the racist reception that new arrivals from the Caribbean faced, from cold hostility to outright violence, but the drama often takes predictable turns, the humour is a bit obvious, and the central characters’ dilemmas are (apparently) solved with remarkable speed and ease in the final episode. As the Guardian’s reviewer said, it needed more grit.

Three Pines

A sadly short-lived adaptation of Louise Penny’s Inspector Gamache series of novels. Alfred Molina is absolutely Gamache, and the episodes are pretty true to the books, although developing a rather interesting sub plot. dealing with the disappearance of an young indigenous Canadian woman. I would have loved to see where it went with that, as well as enjoying the adaptations of further novels, but it came to an untimely end.

Time

I haven’t seen the first season but clearly that didn’t matter as season 2 is set in a women’s prison, with only one character overlapping. Stunning performances from Jodie Whitaker, Bella Ramsey and Tamara Lawrance.

Tokyo Trial

I saw a couple of documentary series about the aftermath of WWII in terms of justice for Nazi war criminals (see below), and this drama series complemented those very interestingly. It’s the equivalent process for Japanese war criminals and it raises the same issues of moral responsibility and grapples with the developing new concepts of crimes against humanity.

The Wire

First time I’ve returned to this series. Mainly because its impact was so huge, it towered so far above most other TV series, and it stayed in the memory so clearly. But a couple of days without internet made me rummage through my DVD box sets and I thought, yes, now is the time to go back to the mean streets of Baltimore. I wondered whether it would have lost its power, but from the very first scene on, it was everything I remembered, and more. I’m kind of dreading getting to Season 4 because I remember how utterly heartbreaking that was. But this is truly superb television.

Wolf

Blackly comic and gruesome crime drama, which leaves you guessing right to the end as to who, why and how. Sacha Dhawan and Iwan Rheon are clearly having a blast.

The Woman in the Wall

Ruth Wilson leads in this often harrowing mystery about the trauma of the Magdalen laundries. The Guardian’s reviewer said that ‘the gothic element, spilling out of Lorna’s mind and home, feels not like a bolt-on to add drama lacking elsewhere but an integral part of the story. A manifestation of the deepest possible horror, beyond reason, beyond words’.

World on Fire

A long-awaited second season for this WWII drama. As with the first, it combines a broad sweep (North Africa, Occupied France, Germany, Manchester) with individual narratives, and this works brilliantly. It does mean that we cut quickly from one scene to another, but that gives it pace and tension, and reinforces the idea that all these things are happening concurrently. It’s pretty accurate – season 1 did make me shout at the TV when a character somehow managed to make his way from occupied Poland to the beach at Dunkirk, but nothing was quite as jarring as that this time. Very much hoping there will be a season 3.

Documentaries:

Amend/13th

Two documentaries which improved my understanding of the US constitution and political structure no end. Amend is ‘a deep dive into the 14th amendment. Ratified in 1868, it gave citizenship to all those born or naturalized in the country and promised due process and equal protection for all people. Amend threads the amendment through the fabric of American history, from its origins before the American civil war to the bigoted violence of the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras, through the tumultuous years of the civil rights and women’s liberation movements, right until today’s feverish debates over same-sex marriage and immigration’. Will Smith presents this, in a style that aims to make a heavy topic rather less so, without airbrushing away any of the horrors of Jim Crow/segregation.

13th does something similar with (obviously) the 13th amendment, but the style is harder edged (the director is Ava du Vernay, best known for Selma). ‘The film takes its title from the 13th amendment, which outlawed slavery but left a significant loophole. This clause, which allowed that involuntary servitude could be used as a punishment for crime, was exploited immediately in the aftermath of the civil war and, DuVernay argues, continues to be abused to this day.’ It’s a tough, challenging watch, and deservedly so.

Beckham

A very enjoyable four episodes, with lots of football to remind me what a wonderful player he was. I’d forgotten quite how vicious the backlash was after that foul – but how much worse would it have been had it been a black player, given the abuse directed at Rashford, Sancho and Saka after their missed penalties cost us the trophy… I rather liked David, and Victoria – considering the absolutely mad life they’ve had, they seem fairly grounded, warm and funny.

The Center will not Hold

A fascinating documentary about Joan Didion, directed by her nephew, Griffin Dunne. I only know Didion through The Year of Magical Thinking (see my books blog), but the film puts that book into context and perspective and makes me want to read a lot more of her work.

David Harewood on Blackface

A few months ago, I was at a community breakfast at my sister’s church, trying to make conversation with an older couple (my father was there too, but is beyond conversation, most of the time). Things started to go awry when the man said something about the cobbles in Mansfield market having been removed because they created problems for wheelchair users – fine, if factual, but the accompanying eye roll was something of a red flag. It got worse, when he made a hand gesture and referred to it as being ‘black and white minstrels’ and his wife chipped in with ‘you’re not allowed to say that anymore, or sing “Baa baa black sheep”’ and he muttered something about how ridiculous it was to try and change ‘our traditions’. I didn’t say anything – didn’t know where to begin with the staggering ignorance, and the staggering arrogance. Perhaps I should have tried, but it was a stressful time, and whereas I knew my father, as he used to be, would have supported my views (he and my mother hated the Black & White Minstrel Show when it was on TV at my grandparents’ home), he would not have been able to follow, let alone contribute to the discussion. Coincidentally, David Harewood’s enlightening and emotional exploration of blackface (with David Olusoga, amongst other contributors) was shown shortly after this. I don’t think I had fully grasped that the minstrel show was in its origins an overt attempt to ridicule black people, at a time when the abolitionist movement was gaining ground. Watching this made me regret not having risked causing a stir at the church breakfast by challenging them…

Evacuation

Harrowing coverage of the evacuation from Kabul, mainly from the point of view of the British troops who took part, many of whom are still very visibly traumatised by what happened, how quickly control of events was lost, and how many people who needed rescue were left behind.

Journey of an African Colony: The Making of Nigeria

A Nigerian-made documentary about this history of Nigeria, this was absolutely fascinating. Having lived briefly in Northern Nigeria (1966-67) I would have liked it to cover the years after independence, and the build up to the Civil War, but its remit was to shed light on the final decades of colonialism and how Nigeria became a nation, about which I knew almost nothing, and which does shed light on the problems that the new nation faced after the great goal of independence was achieved.

Mixed Britannia

The late, lovely George Alagiah presented this exploration of ‘mixed’ marriages in Britain, with some heartbreaking and harrowing history but also some wonderful interviews with couples who knew they would face ostracism and even violence but went ahead anyway and built lasting, loving families. It was nice to see the coverage of Peggy Cripps and Joe Appiah’s wedding in 1953, because they lived on the campus of Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology at the same time that my family was there, and Peggy and my mother were friends.

November 13: Attack on Paris

I vividly remember that evening, following what was happening via social media, and then waking the next morning to the full horror of it all. This documentary was harrowing, but the survivors who were interviewed were so insightful, and so articulate that it shed a great deal of light, particularly on the events at the Bataclan. I also saw Paris Memories (see above), a fictional account of the trauma experienced by the victims.

Reframed: Marilyn Monroe

Last year I watched (and regretted watching) Blonde and read as a corrective to that abomination Sarah Churchwell’s book on Monroe, which is very much where this film takes its stand, with lots of (female) talking heads on every aspect of Monroe’s life, and the movie industry.

Rise of the Nazis: Manhunt/Nuremberg/The Devil’s Confession

Various aspects of the aftermath of the end of the Third Reich, focusing on the attempts to track down Nazis who had slipped away in the chaos (with the help of various parties, including the CIA and the Vatican) and on the trials, at Nuremberg and subsequently. See also the drama series, Tokyo Trials, about the legal aftermath in Japan.

Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America

Based on the book by Ibram X Kendi, this documentary is fascinating and hard-hitting, but not without hope for the future. It’s fronted by black women academics and activists, including Angela Davis, who speak both as academics/activists but also very personally and passionately.

Ukraine: Ground Zero/Ordinary Men

Two documentaries which focus on the ‘Holocaust by bullets’, where Jews were massacred on the Eastern Front by special SS units. It’s a necessary focus, as the language of the Holocaust has come to use Auschwitz and gas chambers as a simplification of the genocide, rather than as examples of where and how.

It intrigues me to look back over the period I’m reviewing and see what patterns emerge. There’s a lot of black history, not only American (from slavery to civil rights) but also the Windrush arrivals and colonial Nigeria – both fiction and documentary. There’s a fair dollop of sci-fi and fantasy and a much larger dollop of crime, fictional and true. WW2 appears to have receded a bit, and what there is emphasises the aftermath, both in Europe and Japan. I’ve probably sated my appetite now for more about the opioid crisis, what with three dramas, one documentary and two books (over on the other blog), but that stuff is fiercely addictive so who knows…

As is usually the case, my watching tends to the dark. Terrorism, war, violence against women, racism, serial killers… Thank heavens therefore for Barbie, for Marvel, and for Who. I know that some might see these as trivial, frivolous, in the face of the world events, and I disagree. Fantasy allows us to explore dark things, the things we fear, in a different way, and to extrapolate not only from the worst that human beings can do, but from the best, to see human beings as extraordinary. I do know that there are no actual superheroes out there to save the day, and that Earth isn’t really under the protection of a Time Lord, but I also believe passionately that human beings can be better, braver, kinder, that we can work together and care for each other. We can allow ourselves through the medium of fantasy to be optimistic, we can allow ourselves to hope. We also need to laugh, even in the face of darkness.

What I read in 2023 – the second half

Posted in Literature on December 15, 2023

This half year seems to have been particularly heavy on the crime fiction. And what’s listed below is not even all of the crime I read – there were some that disappointed me, and as always I prefer to share enthusiasm rather than disappointment (although I am not uncritical of the books that I have chosen to review), and there were some that were perfectly enjoyable but about which I could say little other than that this was another cracking title in x series by y. I turn to crime (as it were) for tension and suspense along the way and a satisfying denouement. But of course the best crime writers (looking at you, Sarah Hilary, Jane Casey, Will Dean, Laura Lippman, Denise Mina, Abir Mukherjee, Mark Billingham, Anne Holt, Louise Penny, Elly Griffiths, Ian Rankin, Mick Herron, Ann Cleeves, Val McDermid, Lesley Thompson and Sara Paretsky, to name only those I’ve read this year) give you more than that – psychological, political, sociological insights into the why and who of crime (on both sides of the law).

If I had to pick the outstanding novels in this half-year (of course I don’t have to, it’s my blog and I make the rules here) I’d say Richard Powers’ The Time of Our Singing and Stuart Evers’ The Blind Light, not only because they took me over completely whilst I was reading, and moved me tremendously, but because both authors were new to me, and so I had no expectations and was bowled over. I also rate very highly Eleanor Catton’s Birnam Wood, and great new stuff from Stephen King (Holly) and Sarah Hilary (Black Thorn).

Non-fiction was heavy on autobiography (Martin Amis, Angela Davis, Joan Didion, Catherine Taylor and Terri White), and biography. Two books on the US opioid crisis which has proven rather addictive as subject matter these last six months, and some grief/bereavement reading. Best/favourites? Catherine Taylor’s The Stirrings, and Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking.

FICTION

Megan Abbott – Beware the Woman

The premiss is one which I’m sure I’ve encountered before, but it’s a fresh take on the set up – a young couple, expecting their first child, visits one of their parents, and things get a bit weird. (Get Out sprang immediately to mind, although the tensions here are not to do with race). There’s a whole lot of gaslighting going on here, the creepiness is built up gradually and cleverly, and it was all very enjoyable, but with an undercurrent that’s really rather serious.

This is a complex and gripping thriller – it’s featured in a lot of end of year Best Of lists, not just mine – which delivers, generously, both intelligence and suspense. ‘Birnam Wood is a dark and brilliant novel about the violence and tawdriness of late capitalism. Its ending, though, propels it from a merely very good book into a truly great one.’

Ta-Nehisi Coates – The Water Dancer

Compelling narrative of slavery, with echoes of The Underground Railroad (like Whitehead, Coates takes the metaphorical and makes it literal), and with a leading role for Harriet Tubman. This isn’t just about slavery though, Coates looks more widely at capitalism, at the oppression of women, at the structures in society that require there to be a hierarchy and someone at the bottom of that who is powerless. Full of pain, inevitably, but of beauty too.

Will Dean – The Last Passenger

A cracking opening (and very different to Dean’s excellent Tuva Moodyson crime novels – I also read Wolf Pack in that series recently) . Caz is on holiday on an ocean liner with her partner, and wakes to find she is, apparently, alone on the ship. Dean pulls this off brilliantly, and every time we (and the protagonist) thinks they have begun to figure out what’s going on, we are blindsided with a new revelation – right up to the final page. It’s irresistible.

Bernardine Evaristo – Soul Tourists

An impromptu road trip for a slightly ill-matched couple which somehow leads to encounters with key figures from black European and Middle Eastern history. I don’t think it entirely worked; perhaps Evaristo was simply trying to do too much, and there are two novels in here, which don’t always mesh. Thoroughly entertaining nonetheless.

Stuart Evers – The Blind Light

A family saga, of lives lived in the shadow of the bomb, absolutely enthralling and moving. It sweeps across sixty years in the lives of its main protagonists, Drummond, Gwen and Carter, but always the focus is on these relationships, always intimate rather than letting the individuals become lost in the sweep of big events. One of my books of the year.

Robert Ford – The Student Conductor

Ford’s writing about music is wonderful, and really made me think about the role of the conductor. But the characters of Ziegler, the lead character’s supposed mentor, didn’t convince me (though he did remind me very strongly of J K Simmons’ character in Whiplash), nor did the oboist/love interest. Very mixed feelings about this one.

Abdulrazak Gurnah – Pilgrims Way

I read Gurnah’s brilliant Afterlives recently, set in what is now Tanzania in the early twentieth century. Pilgrims Way is closer to home, geographically and chronologically, and its scope is much narrower, dealing with one man, Daud, an immigrant whose life has not gone to plan, and who deals with his disappointment and disillusionment with sardonic humour and leaps of imagination. It’s often funny, but always dark and troubling.

Mohsin Hamid – The Last White Man

A fable in which a white man wakes up one morning and looks in the mirror to see that he’s no longer a white man. He has to navigate the world now as a black man, and everything is different. At this point it made me think of Arthur Miller’s novel, Focus, in which a man gets new spectacles, which make him look Jewish to some people, and those people conclude that he must be Jewish. But Hamid’s tale goes in a different direction and I found it beautiful.

Sarah Hilary – Black Thorn

A stand-alone from Hilary, whose Marnie Rome detective novels are amongst my favourite contemporary crime thrillers. Here the focus is not on the police, who play a more peripheral role, but on a small community of people who, we learn at the beginning, have encountered some catastrophe, and we gradually learn what, how, who, why… It’s beautifully done – incredibly tense and creepy and that tension is maintained as truths emerge.

Catherine Ryan Howard – Run Time

This is gripping stuff! Layers upon layers, super tense atmosphere, the plot revolves around the filming of a horror movie, in an actual cabin in the woods…

Clare Keegan – Foster

A novella of real delicacy, beauty and heartbreak. A child goes to stay with strangers when her mother is pregnant again, and finds herself with space and time to think and breathe, as she tries to understand her new guardians, and her own mother.

Stephen King – Holly

Holly first appeared in King’s Mr Mercedes, but he clearly loved her, because her role became increasingly important, in the other two books in that trilogy, but also in The Outsider. And here she is front and centre, as the title promises. This is King at his best, conjuring up creeping unease and tension, creating monstrous human beings and monstrous deeds, without ever letting the monstrous have it all their way, because he also creates people like Holly, who will, as she has done since Mr Mercedes, stand in its way. We love her as much as King does.

Laura Lippman – Prom Mom

Lippman’s plots are as twisty as the run of the mill psychological thrillers which bill themselves as having ‘a twist that you’d never predict’. But unlike so many of those, the twists are earned by careful plotting and, most of all, by character building. Our sympathies shift as we understand the protagonists better but understanding them is key to the twists in the narrative, rather than just upturning everything we’ve previously been told. And we do feel for these people, all of them, however weak and flawed they turn out to be.

Luke McCallin – The Man from Berlin

McCallin’s protagonist is an Abwehr officer, a former policeman, who is trying to solve brutal crimes in the context of a regime which is itself brutal and criminal. It’s similar territory to Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther series, and whilst I have only read one of this series so far, I will follow it up because I’m fascinated to see how Gregor Reinhardt navigates this dangerous, brutal world.

Cormac McCarthy – All the Pretty Horses

McCarthy’s prose is as rich as his dialogue is spare – sometimes the former feels just a bit too much, but at best its richness is beautiful rather than indigestible. His protagonist is a 16 year old boy who’s just been turfed off his grandfather’s ranch, and decides to try his luck in Mexico, along with his best friend, and their horses. John Grady Cole is someone we quickly learn to care about – like so many at his age, he thinks he understands the world rather better than he does, but he is in many ways an archetypal Western hero, with principles and courage and loyalty. It’s a world I don’t really understand but this is a compelling and moving novel. It’s the first in a trilogy, so I may venture on to Vol. 2 (The Crossing) at some point.

Denise Mina – Field of Blood

Mina weaves a fictionalised version of a real crime, and a real case of miscarriage of justice together with her usual skill. Paddy Meehan too finds her job (as a copyboy at a newspaper) and her personal life getting dangerously intertwined. She’s an engaging character, not perfect in judgement or actions, but I will look forward to reading the other books in which she features.

Abir Mukherjee – A Rising Man/A Necessary Evil

The first two in a crime series set in India in the early 20th century, with a British/Indian team, exploring all the tensions that creates (between the two of them, and with wider society). The context is fascinating, the writing excellent, and the voice of Wyndham, the British officer, is convincingly that of an enlightened man of his time, rather than a stand-in for a contemporary reader.

Richard Powers – The Time of our Singing

A truly immersive book, which I started off reading in short bursts until I realised that wouldn’t work. It’s a profoundly musical book – I half intend to create a playlist of all of the pieces of music that play a part in the narrative, although what I would really want would be those pieces performed by the characters in the book. It’s also brave (or foolhardy) enough to tackle race, as the protagonists are a mixed-race family (white father, black mother) in the US in the mid-twentieth century. I found it beautiful, powerful, very moving.

Anya Seton – My Theodosia

I read this, along with everything Anya Seton wrote, as a teenager, and revisited it because I was reading the biography of Alexander Hamilton (see below), who was killed in a duel by Theodosia Burr’s father. But, my god, this is an appallingly, sickeningly racist book. I wondered whether Seton was simply trying to convey the perceptions of a young woman in a society where slavery was still entrenched (although we are told that Theodosia thought slavery was wrong), but no, Seton wrote this in 1942 as a young woman in a post-slavery but pre-civil rights society, and it is impossible to escape the conclusion that these were her perceptions too. Her descriptions of any black characters are contemptuous, the n word is on every page. Of course, this is a novel of its time (and about a time when things were worse), but it made it a grim read and it was hard to care about Theodosia or her father when one had to wade through all of this. I can’t remember how I felt about the book when I first read it, but I think that, although I was more aware of racial politics than my contemporaries at school in Mansfield, having grown up in West Africa with parents who were passionately anti-apartheid, and having a keen interest in the civil rights/black power movements, I was at the same time used to encountering these attitudes and this language, unapologetically presented, in a way that we no longer are.

Elif Shafak – The Island of Missing Trees

I’ve enjoyed a couple of Shafak’s other books, and I liked a lot of things about this, but there was way too much whimsy for my taste. Whole sections are narrated by a fig tree, and whilst I can see how this connects with the history of the divided island of Cyprus, and with the stories of the main protagonists, I speed-read through these bits (sorry) to get back to the human characters, with whose stories I could more fully engage.

Khushwant Singh – Train to Pakistan

A novel about Partition, published in 1956, so not long after those events, set in a fictional village near the new border. Singh was a lawyer, diplomat and politician as well as a writer. His perspective here is to explore the cataclysmic events taking place across the sub-continent through a close focus on this small place, its dignitaries and officials and local ne’er do wells, who are portrayed with sharp wit and humour, even whilst the undercurrent of imminent tragedy is getting stronger.

Noel Streatfeild – Saplings

I’ve read many/most of Streatfeild’s children’s books, and her Vicarage trilogy but had no idea of this one’s existence until I spotted it in the catalogue of the brilliant Persephone Press. It’s the story of four children in wartime, of losses and betrayals and insecurity, and it’s a deep dive into ideas about attachment and loss and their effects on the young. If that makes it sound offputtingly theoretical, it isn’t – her novelist’s gift is to make us care about these children and what happens to them, and it’s very moving.

Marion Todd – See Them Run

Very enjoyable police procedural, set in the area around St Andrews, where I visit a couple of times a year (there’s always a peculiar fascination in reading thrillers set in familiar territory). Will read more.

Miriam Toewes – Women Talking

Recently made into a rather good film (see my screen review blog). This is horrifying, all the more so because the case is real. Girls and women in a Mennonite community in Bolivia were drugged and raped by members of their own community, and despite the perpetrators being exposed and some jailed, the women were left with no redress, and no protection. The book is, as the title tells us, women talking – and they talk about survival, about whether they should stay in the only place they know or leave and take their chances in what may be a hostile world. The tension – and it is very tense indeed – comes both from the disagreements amongst the women and the depths of trauma that they reveal, and from the knowledge that they could so easily be prevented from leaving, when the men return.

NON-FICTION

Martin Amis – Experience

I’ve only read one of Amis’s novels, and I hated it. Time’s Arrow was clever, but in a way that repelled me, and that put me off trying any of his other novels. So, in the aftermath of his death, I thought I might encounter him through his memoir. I liked him more here – he is self-critical, he can find his past self ridiculous and blameworthy, and he can be generous to at least some of the other people in his life. And in his writing about the disappearance and murder of his cousin Lucy Partington by Fred and Rosemary West, there is real heart, real grief. I still don’t want to read any of his novels though.

Anita Anand – Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary

Biography of an extraordinary woman. Daughter of a Maharajah, god-daughter to Queen Victoria, and as the book’s title tells us, suffragette and activist. Absolutely fascinating. Sophia herself remains enigmatic, but her engagement with the ‘advancement of women’, and with campaigns in support of Indian lescars, Indian troops in WWI, and the cause of Indian self-determination was bold and brave, and through her we see a varied and colourful cast of characters, both Indian and British.

Jeanine Basinger & Sam Wasson – Hollywood: An Oral History

The story of Hollywood told through interviews with people who were there – directors, actors, writers, studio bosses. The interviews, held in the American Film Archives, cover all aspects of movie-making so inevitably some sections are more interesting (to me) than others, though overall it is fascinating and enlightening, and very entertaining.

Ian Black – Enemies and Neighbours: Arabs in Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917-2017

In the wake of the 7 October Hamas attacks, and the Israeli bombardment of Gaza, I wanted to understand more about why we are where we are and why this is such an intractable situation. I knew some of the story, of course, but I wanted a rigorous historical approach, non-partisan as far as is possible. Black’s book fits the bill. It is, of course, deeply depressing, but it is impossible when reading it to take a simplistic view of causes or possible solutions.

Ron Chernow – Alexander Hamilton/Mike Duncan – A Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution

I’ve grouped these two biographies together because their subjects were not just contemporaries but friends, and there are many parallels between them. Reading up on Hamilton is prep for going to see the musical in Manchester in February – when I watched it on TV I realised how sketchy my knowledge of that period of American history was, and whilst I dare say it’s not compulsory to do the reading before enjoying the music, it’s very much me… I had a better grasp on Lafayette’s story because my History A level covered the French Revolution and its aftermath, and I’ve read around the subject since. Both Hamilton and Lafayette were extraordinary men who achieved far more than anyone expected of them, at quite a young age, and these accounts bring them to life whilst providing a thorough, well-researched and readable historical context.

Angela Davis – An Autobiography

Davis was a hero of mine during my teens. I read a lot about the activists in the black power movement but was inevitably drawn to Davis – her charisma, her passion, her image. Women, Race and Class is brilliant, and so is this. It was originally published in 1974 and now has a series of prologues written for each successive edition, which shed light on how her perspectives have changed and how she responds to more recent events.

Joan Didion – The Year of Magical Thinking/Sarah Tarlow – The Archaeology of Loss: Life, Love and the Art of Dying

Two books that I was drawn to because they addressed how we live after the death of a partner. Didion’s book was recommended to me, with the caveat that I shouldn’t read it too soon – there are of course no rules as to how soon is too soon, and I think I got it about right. It was in places a very tough read – her description of her husband’s death had so many echoes of what happened to me – but her insights into the process she went through were profound and powerful (my copy of the book now has many sections highlighted so I can return to them when I need to). Tarlow ventures out further from her own experience to ruminations on how we (now and in the past) deal with death and loss, and it’s fascinating and often moving. It spoke to me less personally than Didion’s account because much of it is concerned with how she became her husband’s carer when he developed a terminal degenerative illness, and how that affected her and their family (my loss in contrast was shockingly sudden). It’s brutally frank and unsentimental about the cost and the loneliness of the carer’s role, and so whilst I was initially drawn to the book because it addressed bereavement, this topic is also vitally important and relevant.

Eddie Glaude – Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and its Urgent Lessons for our Own

I have loved Baldwin’s writing since my teens, when I read Go Tell it on the Mountain, and found his voice so compelling that I read over the subsequent years all of his other novels and essays. Glaude considers Baldwin’s evolving views on race in America, and as promised draws out lessons, and he conveys both Baldwin’s despair and the hope he held on to despite everything. It’s not a hagiography, he does not treat Baldwin as a sage, but as a passionate, deeply insightful, direct and honest writer whose insights into America are as relevant as ever.

Beth Macy – Dopesick: Dealers, Doctor and the Drug Company that addicted America/Chris McGreal – American Overdose: The Opioid Tragedy in Three Acts

See my Screen blog for the two dramas and the documentary that I watched on the topic of the US opioid crisis. I clearly became somewhat obsessed with this topic, having read Demon Copperhead and then watched the Netflix drama Painkillers… These books follow similar ground, but have a different approach. American Overdose focuses more on the politics and the perpetrators: ‘McGreal’s book reads like a white-collar The Wire, with a cast of characters determined to exact as much money as possible regardless of the human cost’. Macy foregrounds the stories of the victims and their families. Taken together they give a full and heartbreaking account that will, and should, make you angry, even whilst it breaks your heart.

Wendy Mitchell – One Last Thing: How to Live with the End in Mind

I’ve been following Wendy Mitchell for some years now, as she navigates life with early onset dementia with humour and honesty. It’s rare to hear the voices of dementia sufferers because they are so often and so quickly unable to articulate their own experience, so Mitchell’s accounts are immensely valuable. This book is different – it looks at how we approach the end of our own life, and how that end can be made more dignified, how we can have some control over when, how, and where. This is a passionate work of advocacy for assisted dying, but Mitchell recognises that the provision that exists in a number of countries generally cannot help her and others with dementia because by the time they would want to be able to check out (the point at which, for example, they are no longer able to recognise their closest family), they will not have capacity (or not be deemed to have capacity) to make that decision. It’s a huge and heartbreaking dilemma, and Mitchell doesn’t offer solutions, but makes a vital contribution to the discussion.

Anthony Seldon & Raymond Newell – Johnson at 10: The Inside Story

‘This is an authoritative, gripping and often jaw-dropping account of the bedlam behind the black door of Number 10 and it confirms that we did not really have a government during his trashy reign. It was an anarchy presided over by a fervently frivolous, frantically floundering and deeply decadent lord of misrule.’ It’s all the more powerful because the authors are far from being anti-establishment figures. It makes it clear that the picture painted by the TV drama Partygate (see my Screen blog) is entirely plausible and consistent with the culture at Downing Street under Johnson. Incredible, and appalling.

Gitta Sereny – The German Trauma: Experiences & Reflections, 1938-2001

This collection of articles from almost forty years of writing about, thinking about and remembering the Nazi era includes much that is fascinating, some that is contentious, and inevitably a vast amount that is horrifying.

Catherine Taylor – The Stirrings: A Memoir in Northern Time

A memoir of Sheffield – of my Sheffield (Broomhill and Crosspool, the University) – was always going to interest me. Taylor is around ten years younger than me, and so she describes the Sheffield she knew as a teenager, whereas I arrived here to go to University. The shadow of Peter Sutcliffe hangs over much of her account, as it did over my life – scared to be out at night, scared even to open the back door to put the milk bottles on the window ledge, praying that Karen from next door would be on my bus so we could scurry home together along School Road, looking over our shoulders and not breathing properly until we were indoors. Taylor’s writing is brilliantly evocative, both of the place and of her own experiences and emotions. As Helen Mort puts it, this is ‘a lyrical account of what cities and their residents witness, how places shape character’.

Dorothy Whipple – The Other Day: The World of a Child

Charming, funny account of a childhood in the very early twentieth century, from a writer whose novels I’ve discovered and loved in recent years.

Terri White – Coming Undone

This is a bleak, harrowing account of how a chaotic and abusive childhood pushed White into crisis as an adult. Her honesty is unflinching. I wondered throughout just how she was managing to function (at least to some extent) in her working life, and, at the end, how she managed to turn the corner into a more stable life. I’d have liked to understand that more, but maybe that’s about me feeling less harrowed, and actually this is exactly the book that White intended and needed to write.

Closer to Fine?

Posted in Personal on October 9, 2023

The second year is harder than the first – that’s the received wisdom. But in that first year, you’ve had to get through the sheer shock, to deal with the grim grind of bereavement admin, to make some of the vital decisions about what you do now, how you live now, and you’ve probably got to the point where you’re functioning, more or less. The first year is so bloody hard that one might be forgiven for thinking that surely, surely, it will get easier. Well… it gets different.

I wrote about this last year, how after that first anniversary, you’ve got a whole year of being without your person, a whole new set of memories, obviously marked and shaped by their absence, but new, at any rate, and maybe some of them are good memories in their own right (not just good, considering). But the price of that is the knowledge that this is now it. This is your life, and it’s not the one you thought it would be, let alone would ever have chosen, but you have to go on, and on. That is a whole new kind of hard.

And somewhere along the way, you may start to drift. When you’ve lost the person with whom you navigated life, the person who anchored you when you needed it, and with whom you looked ahead and planned and anticipated and hoped, it is perilously easy to drift.

You’re driftwood, floating underwater

‘Driftwood’, Travis

Breaking into pieces, pieces, pieces

Just driftwood, hollow and of no use

Waterfalls will find you, bind you, grind you