cathannabel

This user hasn't shared any biographical information

Homepage: https://cathannabel.wordpress.com

2024 Reading – the second half

Posted in Literature on December 6, 2024

My reading this year has been the usual eclectic mix. I normally (normal for me, I hasten to add) have four books on the go at any time. One will be in French, maintaining a fairly recent resolution (so far this half year, de Beauvoir, Gide, Mauriac, Fatou Diome and Francois Emmanuel, of whom the last two were new to me). At least one will be non-fiction. One will be on the Kindle, two will be by my bedside to read before I turn out the light, and one in my library room (currently the French one).

Having brought so many books, half-forgotten in many cases, down from the attic this year, I’m instituting a new ‘rule’ for 2025 – one of the four books will be a re-read. Or, possibly, a first read if it’s one I’ve had for yonks but honestly can’t recall whether or not I did read it (there’s a lot of M’s sci-fi stuff that’s in that category). But there are also books the mere sight of whose covers made me yearn to revisit them. And whilst life is short and there’s so many great new books out there, there are also so many great old books that absolutely deserve to be savoured all over again.

I read a lot of crime fiction, but would not want to be reading more than one in that genre, as clues and corpses could easily get in a muddle. When it comes to crime fiction in particular, I haven’t listed everything I read, not because it wasn’t any good, but because ongoing series are hard to review without just repeating myself about how good, e.g. Elly Griffiths or Val McDermid is.

There are a few books here that slide across genres – Thomas Mullen’s Blind Spots is crime + sci-fi, Leonora Nattrass’ Blue Water is crime + historical fiction. For more straightforward historical fiction the stand-out is Maggie O’Farrell’s The Marriage Portrait. And for books that don’t present us with the world that we know or that existed, or not straightforwardly, there’s Evaristo’s alt history/alt geography Blonde Roots, Mullen, Jenny Erpenbeck’s End of Days which plays around with how death normally operates, and Kate Atkinson’s short stories (see below). I was pleased to discover some new novelists in this batch, notably Nathan Harris, Caleb Azumah Nelson, Margot Singer and Anna Burns – my top books of this half year are Nelson’s Open Water and Burns’ Milkman, and in non-fiction, Paul Besley’s The Search. As always, I try to avoid spoilers, but do proceed with caution.

Fiction

Kate Atkinson – Normal Rules Don’t Apply

I love Atkinson – Life after Life in particular is one of my absolute favourite books. I’m not generally a fan of short stories but these are – as the title suggests – quirky and sometimes baffling, as well as being often very funny, and definitely need to be re-read asap.

Simone de Beauvoir – Les Belles Images

Reading this, I felt as if it should be one of those French films where elegant people sit around talking about ideas, when they’re not sleeping with each other’s partners. Isabelle Huppert should be in this. I’ve not found it an easy read, partly because the narrative voice switches between our protagonist Laurent, and a narrator, without the distinction always being clearly made on the page. It’s short on event (another reason why it should be one of those French films), very introspective. Worth persevering, because it’s intelligent and perceptive and sharp, and the discussions they have are still pertinent fifty years on.

Mark Billingham – The Wrong Hands

The second in his new Declan Miller police procedural series. Miller is infuriating, but funny and human (though I’m not sure he’s quite different enough from Tom Thorne, about whom the same things could be said), and the crime here is woven together with his own search for truth about the death of his wife, which gives it a lot of heart.

Anna Burns – Milkman

I’ve been meaning to read this for a long time – urged on by my Belfast-born sister-in-law in particular – and I’m so glad I did. It’s darkly funny and terribly sad and horrifying and the people in it blaze with individual life, despite not being named.

Candice Carty-Williams – People Person

I loved her debut, Queenie but this didn’t quite work for me. It started off brilliantly, with the crackling dialogue that was so enjoyable in Queenie, and the deft characterisation of the group of half-siblings and their hopeless father. But the event that dictates the rest of the plot and what flowed from it just seemed so improbable, and then it all got resolved rather too neatly. A lot to enjoy along the way but flawed.

Fatou Diome – Le Ventre de l’Atlantique

A Senegalese woman, making a living (just about) in France, talks on the phone to her younger brother who (along with many of his contemporaries) is desperate to make the same journey, with dreams of being a professional footballer. Through their phone conversations and her own account of her life in their village, we explore those dreams and the realities that the dreamers don’t want to face, all with the backdrop of the 2000 European Cup and the 2002 World Cup.

Francois Emmanuel – La Question humaine

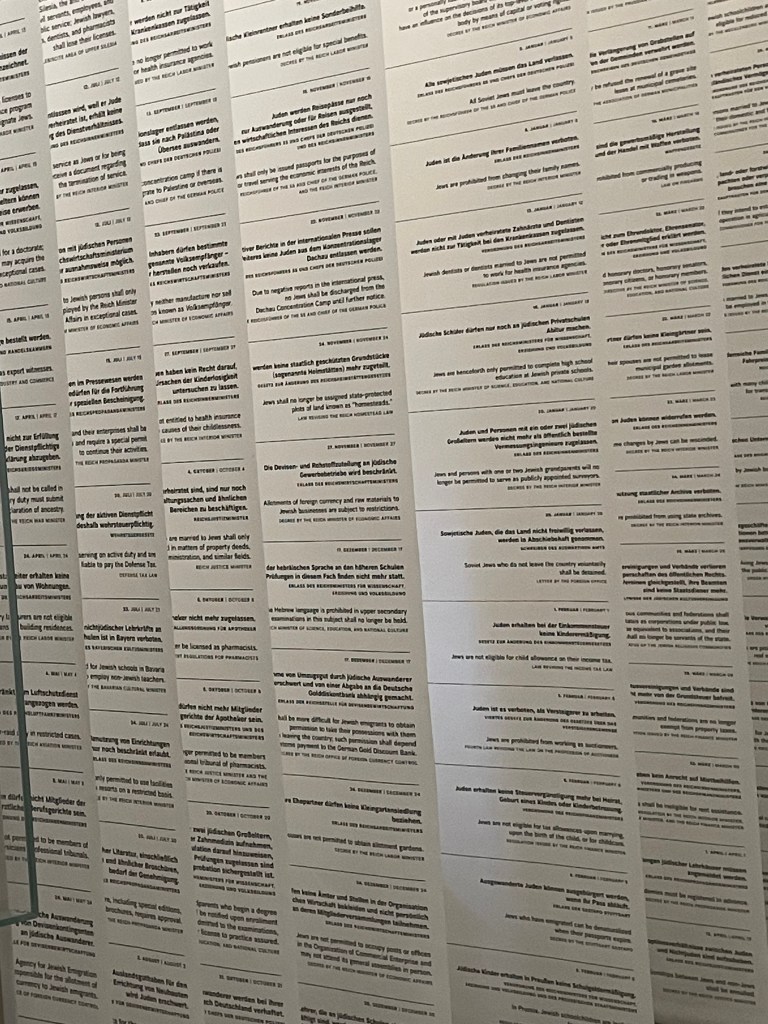

I saw the film based on this – Heartbeat Detector, starring Matthieu Amalric – some years ago and it’s pretty close to the book. A psychologist in the HR department of the French branch of a German firm is asked to investigate the fitness of the CEO and finds himself investigating complicity or direct involvement in the Holocaust. At the heart of it is an exploration of language – the inhuman language of memos dating from the early phases of the Holocaust, and the reductive language of HR practice in large corporations.

Jenny Erpenbeck – The End of Days

The structure frequently wrong-footed me at first – characters are unnamed – it’s the daughter, the mother, the grandmother – and so as we move around in the chronology those relationships change too. Worth the effort to focus. The central conceit reminded me of Kate Atkinson’s Life after Life – a life ends, but it need not have, and what if it didn’t end then, but a bit later, or much later than that? Compelling and moving.

Bernardine Evaristo – Blonde Roots

An alternative world, where the slaves are white, their owners African. It’s not a straight reversal of history, geography has been adjusted too. It’s funny – I love the scene where the white peasant family raise the newborn to the heavens to see ‘the only thing greater than you’, a skit on that same scene in Roots, and perhaps on the Lion King too… The Independent said, ‘Running through these pages is not just a feisty, hyperactive imagination asking “what if?”, but the unhealed African heart with the question, “how does it feel?” This is a powerful gesture of fearless thematic ownership by one of the UK’s most unusual and challenging writers’.

Sebastian Faulks – Charlotte Gray

I think I read this slightly too soon after Simon Mawer’s The Girl who fell from the Sky/Tightrope which has a very similar plot (young female SOE agent parachuted into France, but with her own agenda). It was worth reading though, and it avoids the clichés of wartime heroics, with a compelling protagonist. Apparently Faulks received a Bad Sex award for this but honestly, I’ve read far, far worse…

Damon Galgut – The Promise

Across the years, from the ‘80s to 2018, a South African family wrestles with the huge changes in society, and with the titular promise, made on her deathbed by the matriarch Rachel, that the family servant, Salome, would be given a house of her own on the family farm. It’s a promise that’s explicitly disavowed, or deliberately forgotten about, or that simply is impossible to keep, but that promise speaks eloquently about South African society and its history. It’s in four sections, each beginning with the death of a member of the family, and each reflecting key episodes in the country’s recent history. In each section we see things from the perspective of one of the family members, although always with dry asides from the narrator to puncture their naivety or complacency. But the person into whom we get the least insight is Salome, who is more of a symbol than a character, let alone a protagonist.

André Gide – La Porte étroite

The only Gide I’d read before this was Thesée, his version of the story of Theseus and the Minotaur, which I read whilst writing my PhD thesis, and preoccupied with labyrinths. That was published in 1946 – this is a much earlier work, from 1909, and with a strong biographical element, as the central relationship between his protagonist Jerome and Jerome’s cousin Alissa reflects Gide’s relationship with his own cousin, who he married, despite his homosexuality. Here the issue is not so much sexuality – the relationship between Jerome and Alissa is intense but spiritual rather than physical, and mired in misunderstandings and things unspoken.

Patrick Hamilton – Hangover Square

Rather a depressing read, TBH. But bleakly funny at times. The Critic said that ‘This novel could not have been written at any other point in history. Hamilton is a great navigator of human frailty in the face of desolation. It is not the bar room drinkers, but the articulation of the tragic lack of power man has over the madness that swirls about him that makes Hangover Square a novel of its time.’

Nathan Harris – The Sweetness of Water

Set in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Harris’s debut novel tells of a white farmer whose encounter with two newly freed slaves both transforms his life, and brings about tragedy. It’s beautifully written, with the central characters all given depth and complexity. It’s about change, and how even the most desired, necessary, righteous social change is traumatic, and not just for its opponents. It’s about how people – individuals and communities – move on from that, about what freedom might mean at this time and in this place. Deeply moving, and with a sense of hope.

Robert Harris – Archangel

Harris never lets me down. We start off in Death of Stalin territory, and then jump forward to the post-Soviet era to meet our protagonist, an academic specialist in Soviet history who gets embroiled in highly dangerous secrets that show how that great dictator is not and perhaps cannot ever be entirely consigned to history. Thrilling up to the final page.

Sarah Hilary – Sharp Glass

The latest stand-alone psychological thriller from Hilary, and it’s another corker, perhaps her best yet. It’s not about twists for the sake of twists (I do go on a bit about this, but it really annoys me, when all credible plotting or character development is jettisoned for the sake of ‘a twist you’ll never see coming’…). Here, character is all, and these characters gradually become clearer, to themselves, to each other and to the reader, but there are loose ends left loose, not tidied away, so we’re still wondering about the protagonists after we’ve turned the final page.

Winifred Holtby – The Crowded Street

Holtby’s second published novel. I’d read South Riding many years ago, and several times – my Mum was a fan – and also Anderby Wold, but this one was new to me. Her protagonist is a young woman who feels a strong sense of familial duty but nonetheless struggles to fit the role that is expected of her. It’s often funny but there’s a deep sadness too, and anger.

Aldous Huxley – Point Counterpoint

A roman à clef about interwar intellectuals (based on, inter alia, D H Lawrence, Middleton Murry and Huxley himself). Like a fugue, the novel unfolds through a series of different voices and different debates, interweaving and recurring in different forms. As such it’s wordy and light on incident, but nonetheless fascinating.

Tom Kenneally – Fanatic Heart

I was looking forward to this – I’d read a few of Kenneally’s books years back and remember liking them, and Fanatic Heart covers an interesting period of history, spanning three continents, from the Irish Famine through to the first stirrings of civil war in the US, through the life of Irish nationalist writer John Mitchel. But the style was somehow so inert. The story was eventful enough, it should have been engaging but instead it dragged, and I ended up skim reading the last chapter or so just to finish it. The story is also cut off before what would potentially have been an opportunity to explore Mitchel’s controversial views on slavery (he was for it), and his loyalty to the Confederate cause during the Civil War. But I’m afraid I didn’t enjoy this enough to read a sequel, if there is one.

Jhumpa Lahiri – The Namesake

Touching, funny account of a young man’s life, from a Bengali family, growing up with a Russian name in the USA. Julie Myerson in the Guardian said that ‘this is certainly a novel that explores the concepts of cultural identity, of rootlessness, of tradition and familial expectation – as well as the way that names subtly (and not so subtly) alter our perceptions of ourselves – but it’s very much to its credit that it never succumbs to the clichés those themes so often entail. Instead, Lahiri turns it into something both larger and simpler: the story of a man and his family, of his life and hopes, loves and sorrows.’

Francois Mauriac – La Pharisienne

Mauriac’s Le Noeud de Viperes was one of the first French novels that I read (in French) without having to, whilst I was at school. I’ve read several of his other novels, and his remarkable clandestine pseudonymous publication Le Cahier Noir, a rallying call to Resistance during the Occupation. He’s a hero of mine – he was in many ways a conservative – family, the Church, his country – but never an unquestioning one, and his questioning led him to challenge the Church’s support for Franco, and to bring his skill as a writer to the Resistance. He was never going to be a fighter (too old, too weedy), but he still risked everything by his activities and associations. This novel was published during the Occupation, under his own name, because it isn’t, at least overtly, about that. It’s the study of a woman whose religious convictions make her seek perfection not only in herself but in those around her, and to deal harshly with those who fall short. As a critique of religious zeal it was controversial enough – but the depiction of a culture of denunciation perhaps does refer obliquely to the Occupation. It’s powerful and Brigitte Pian, the ‘Woman of the Pharisees’ is a horrifying creation.

Arthur Miller – Focus

I was prompted to re-read this by watching Joseph Losey’s film Mr Klein (see my screen blog). This is Miller’s only novel and it’s premiss is a man who gets a new pair of specs and realises he now looks like a Jew, and that people around him are suddenly seeing him as a Jew. It’s a powerful and shocking account of antisemitism in the US at the end of WWII, and all the more interesting because the protagonist is himself a repository of antisemitic and other racist prejudices (unlike, for example, Gregory Peck’s character in Gentleman’s Agreement, who is noble and righteous and allowing himself to be seen as a Jew consciously and deliberately).

Thomas Mullen – Blind Spots

I have read and loved Mullen’s trilogy (Darktown, Lightning Men and Midnight Atlanta) dealing with Atlanta’s first black cops in the era of segregation and civil rights protests. This is completely different – we’re in an unspecified future, where everyone, worldwide, gradually lost their sight. A technological solution has been found (even if it’s not available, or acceptable, to everyone), downloading visual data directly to people’s brains. But then, it gets hacked, and no one can really trust what they’re seeing… It’s a sci-fi crime thriller, which is completely gripping, but also thoughtful and thought-provoking.

Leonora Natrass – Blue Water

A cracking historical mystery, set in the days of the American Revolutionary Wars, and we’re all at sea, en route to Philadelphia with a disgraced FO clerk, who is trying to ensure that a vital treaty will reach the Americans in time to stop them joining France’s war on Britain. This is the second in a series so I should really have read Black Drop first, but thoroughly enjoyed this one nonetheless and will backtrack to its prequel asap.

Caleb Azumah Nelson – Open Water

Stunning debut from a young British-Ghanaian writer, with a second-person narrative that involves the reader intensely in the protagonist’s thoughts, emotions and experiences. It’s about love, race, masculinity. The i review describes it as ‘an emotionally intelligent and tender tale of first love which examines, with great depth and attention, the intersections of creativity and vulnerability in London – where inhabiting a black body can affect how one is perceived and treated’.

Maggie O’Farrell – The Marriage Portrait

Gorgeously written historical novel, beautiful and tragic and very memorable. Its heroine is Lucrezia de’Medici, married at 15 to the Duke of Ferrara, whose early and suspicious death inspired Robert Browning’s ‘My Last Duchess’.

Ann Patchett – The Dutch House

This almost sounds like a fairy tale – a magical house from which the children are driven out by their stepmother. But for all of the motifs from those archetypal narratives, it’s really about how we deal with the past when the past has hurt us. Maeve (an extraordinary creation) and Danny, the two exiled children, struggle with and find different approaches to this. As the Guardian reviewer put it, Patchett ‘leads us to a truth that feels like life rather than literature’.

Richard Powers – Orfeo

I discovered Powers last year through The Time of our Singing. Like that book, this one is suffused with music. The Independent reviewer said ‘There are passages that make you want to rush to your stereo, or download particular pieces to listen to as you read — Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder, Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time — and others that seem to offer that same experience for pieces you will never hear, pieces composed by Powers’s composer hero, Peter Els.’ It’s not just about the subjective experience of music, it’s about composition, and microbiology and technology, and it’s absolutely compelling.

Margot Singer – Underground Fugue

Another novel that invokes musical form (see also Huxley’s Point Counterpoint). In this case, fugue is both structure – there are four voices here, which alternate and interweave, and connect or echo each other in different ways – and psychological state – all four are exiled and unrooted (and there’s a connection too to the case of the so-called ‘Piano Man’). As these stories interconnect, we move closer to the climactic event of the novel, the 7/7 London bombings. Beautifully written, suffused with a sense of loss.

Cath Staincliffe – The Fells

A police procedural dealing with a cold case – the discovery of a skeleton in some caves in the fells. As always, Staincliffe is interested not just in the crime, and who was responsible for it, but in the ramifications of the crime, the effects on the family and friends. And as always, she makes you believe in her characters, including her new detective duo, and care about them.

Elizabeth Strout – The Burgess Boys/Lucy by the Sea

I do love a Strout. As always, these novels connect with each other, and with others of Strout’s oeuvre. The Burgess brothers connect here to Lucy Barton (via Bob), and we also encounter (indirectly) Olive Kitteridge and the protagonists of Abide with Me – there are more links than those, and I think some kind of a flowchart is called for. Lucy is a Covid novel, it starts with Lucy’s ex-husband William insisting on taking serious steps to isolate the people he cares about as the pandemic looms, and it explores the strange world that we all inhabited then with Strout’s remarkable insight and empathy.

Douglas Stuart – Shuggie Bain

This is a tough read. It’s brilliantly written, with profound sympathies for its characters, including some of the more hopeless ones, but most of all for Shuggie as he tries to survive a chaotic childhood and navigate a path to some kind of stability. There were many moments when I feared how this would end, when a brief period of hope ended in yet another heartbreaking betrayal or failure, but ultimately there is some hope. Just enough.

Kit de Waal – Supporting Cast

These short stories connect to de Waal’s novels – as the title suggests they take characters who played a supporting role in those narratives and bring them to the foreground. As always with de Waal, these people, the lost and the losers, are drawn with tenderness and understanding, and I found them very moving.

Colson Whitehead – Crook Manifesto

A brilliant sequel to Harlem Shuffle. We’re now in the 70s, and furniture salesman Ray Carney is trying to stay on the right side of the law, but things get messy… The writing is marvellous, edgy and with bleak humour. As the Independent says, ‘the blend of violence, sardonic observation and out-and-out comedy reflects Whitehead’s ability to neatly balance the trick of writing both a homage to, and affectionate tease of, noir crime fiction’.

Non-Fiction

Albinia – The Britannias

Alice Albinia takes us island-hopping, and on each of the islands that surround Great Britain, she explores the history (going back to ancient times, and moving gradually forward to our own), folklore, landmarks and traditions, weaving in her own personal history and the conversations she has with locals and fellow-travellers. A lovely, intriguing read.

Paul Besley – The Search: The Life of a Mountain Rescue Dog Search Team

I probably would not have come across this book had I not known its author. And that would have been such a loss. I’m not particularly a dog person – that is, I’ve never lived with a dog, and there are only a few that I have got to know at all well (Alfie, Loki and Bentley). I did have my own encounter with Mountain Rescue though, when I was a teenager with a small group on a church youth hostelling trip who got stuck in awful weather on Great Gable and I can still vividly remember hearing and then seeing our rescuers arrive, with duvet coats and hot chocolate and the relief and joy and gratitude that I felt. The book describes Paul’s own experience of being rescued (a great deal more dramatic than mine) and subsequent involvement with Mountain Rescue, culminating in training a dog, Scout, to work with him to track people who need help in the hills. It’s that training process that forms the bulk of the book, and it’s extraordinary – fascinating and moving and gripping. The title turns out to mean much more than the literal search for those lost bodies – it’s a very personal search for meaning, for a way of living well and in the present, for contentment even in the toughest of times. Do read it, whether or not you are a dog or a hiking person – it’s quite remarkable.

Jarvis Cocker – Good Pop, Bad Pop: An Inventory

Not a memoir. Rather, this is Jarvis rummaging in his attic and telling us stories about some of the stuff he finds there, whilst debating whether to keep or get rid of each item. It’s very engaging, playful and tricksy (just how random are these random items? Were they all actually in that attic at the start of the project? Did the things he tells us he decided to ‘cob’ (a Sheffield word – albeit not one I’m familiar with – for chuck out) actually get cobbed?). And along the way lots of brilliant anecdotes about Jarvis’s youth and the early days of Pulp.

Joan Didion – Blue Nights

I read The Year of Magical Thinking last year, just long enough after the sudden death of my husband. That book deals not only with her husband’s death but with the serious illness of their daughter Quintana, who was in hospital, unconscious when he died, and after an initial recovery became seriously ill again, dying just before Magical Thinking was published. Blue Nights tells – in a non-linear fashion – the story of Quintana’s adoption, her issues with depression and anxiety, her illness and death, through Didion’s eyes. Didion shows, with brutal clarity, how little she understood her daughter, and it offers no healing insights into dealing with such a loss. Cathleen Sohine wrote in the NY Review of Books that ‘Blue Nights is about what happens when there are no more stories we can tell ourselves, no narrative to guide us and make sense out of the chaos, no order, no meaning, no conclusion to the tale’. It’s utterly bleak. Whereas Magical Thinking is an act of mourning, Blue Nights, permeated by Didion’s sense of failure as a mother, and failure to understand Quintana, is a cry of despair.

Jeremy Eichler – Time’s Echo: Music, Memory and the Second World War

Brilliant, fascinating and eminently readable. A study of four composers (Richard Strauss, Schoenberg, Britten and Shostakovich) and a key work by each, responding to World War II and the Holocaust in particular. It generated a powerful playlist: Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw, Strauss’ Metamorphosen, Britten’s War Requiem and Shostakovich’s 13th Symphony (specifically the 1st movement, the Adagio, often referred to as Babi Yar) and along the way lots of other pieces are discussed, with such clarity that one almost feels as if one can hear them.

Paul Fussell – The Great War and Modern Memory

Fascinating study – published in the ‘70s – of how the ‘Great War’ was portrayed in poetry and fiction, how literary references, mythology and religious ideas permeated these portrayals, along with a strong strand of homoeroticism. Some of the work Fussell explores is familiar to me (Owen, Sassoon, Graves), some not at all, but it’s full of interest and new insights. I was particularly struck by how the ‘literariness’ of the accounts was not restricted to the officer class but is present in diary and memoir from other ranks too, suggesting a widespread familiarity with, e.g. Shakespeare and Bunyan.

Rebecca Godfrey – Under the Bridge: The True Story of the Murder of Reena Virk

An insightful account of the murder, carried out by a group of teenagers, of another teenage girl, a bullied outsider. I watched the TV adaptation of this, which oddly makes Godfrey a protagonist, getting directly involved in the investigation, and having a personal history that connects her to the suspects, none of which is actually what happened. It’s odd because it derails the drama, which really needs no embellishment. The book is much better than I was expecting, having been irritated by the dramatization (but sufficiently intrigued to see what the source material actually said).

Richard Holmes – The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science

A rather wonderful account of science in the Romantic era – Herschel and Davy, Mungo Park and Joseph Banks. There are important women here too, most notably Caroline Herschel and Mary Somerville. Very readable, and not just for historians of science – one of the fascinating things about this period is that people weren’t silo’d into arts or sciences as later generations, including my own, tended to be – William Herschel was a composer and Humphrey Davy a poet.

Stuart Jones (ed.) – Manchester Minds: A University History of Ideas

Full disclosure – I contributed a small ‘vignette’ to this volume, on W G Sebald and Michel Butor. But there’s masses of interest here, all marking the 200th birthday of the University of Manchester by celebrating some of its most notable and influential figures. I was drawn to the outsiders or exiles amongst them – like economist W Arthur Lewis, from St Lucia, Gilbert Gadoffre whose time at the University was interrupted by a spell of activity in the French Resistance, Eva Gore Booth, the Irish poet and activist, and philosopher Dorothy Emmett, plus a number of Jewish academics who had left Europe either because of pogroms in the East, or the advent of the Nazis.

Hilary Mantel – A Memoir of my Former Self

A collection of Mantel’s short non-fiction, on a wide range of topics, some autobiographical (these overlap with Giving up the Ghost, a memoir that she published in 2010), some film and book reviews, and most enjoyably and interestingly her Reith lectures on writing historical fiction. As in her novels, she is sharp, funny, and sometimes fierce – her account of how her endometriosis was dismissed by a series of doctors as just female neurosis is utterly enraging.

D. Quentin Miller (ed.) – James Baldwin in Context

A collection of short essays on aspects of Baldwin, his life, his novels, his politics. I’ve immersed myself in Baldwin periodically over the years (first as a teenager when I discovered the novels and short stories, then a couple of years ago inspired by Black Lives Matter, and now for his centenary), and there is much to be savoured here, that can enrich my understanding. I supplemented the reading (I also re-read Go Tell it on the Mountain, and I am not your Negro) with watching some of Baldwin’s interviews, and as always, I find his voice so very compelling. He doesn’t do soundbites or inspirational quotes – when he talks about politics it is all about narrative, the narrative of the African American chained and trafficked and exploited, and then subjected to segregation and the daily evidence of white hatred. Rewatching his ‘debate’ with Paul Weiss was rage-inducing, Weiss’s complacency in his own privilege staggering, but Baldwin’s narrative overwhelmed him. His speech and his writing have a rhythm, a beat, that comes from the church (he was a preacher in his late teens), and from blues and jazz. He’s never less than piercingly articulate, and never less than fiercely passionate, but more than that, his humanity always shines through.

Graham Robb – The Discovery of France: A Historical Geography from the Revolution to the First World War

It’s described as historical geography but it’s also what I would have called social history – it’s about the people who didn’t make it into the history books, and who were for the most part buffeted by Great Events rather than playing an active role in them. And really, as the title suggests, it’s about how little the concept of ‘France’ meant to most of those people, vast numbers of whom did not speak any language resembling French (perhaps one of the reasons why the Académie is so protective of that language now). It also provides a fascinating context for the 19th century novels I’ve been reading since my teens – Balzac, Flaubert, Zola.

Sathnam Sanghera – Empireland: How Imperialism has Shaped Modern Britain

My schooling until the 11+ year was in two newly independent West African nations. Whilst I mixed primarily with other ‘expatriates’ I could not be unaware (and my parents were profoundly aware) of the reasons we were out there, and how the legacy of empire was still playing out. My understanding may have been primitive (I was 9 when we left) but it influenced my thinking about so many things as I grew up. So it was fascinating to read Sanghera’s exploration of the ramifications of our imperial history in British culture and politics. It is clear-sighted and forward looking, and asks what we do once we have recognised what empire did to its overseas subjects and what it did to those who grew up here in its shadow.

Claire Wills – Lovers and Strangers: An Immigrant History of Postwar Britain

The story of immigrants from the wreckage of the war in Europe, from Ireland, from the Caribbean, from across the Commonwealth, at work, at home and at play. It’s a rich and varied picture – the experiences of immigrant life varied enormously as one would expect depending on why they came, where they came from and who they’d been in their previous life. Some of these stories are familiar but a great many are not, and it is good, in particular, to get beneath the generalisation of ‘Asian’ to explore the very different communities who arrived, with different expectations, and different challenges to their integration.

Twenty Films

Posted in Film on November 3, 2024

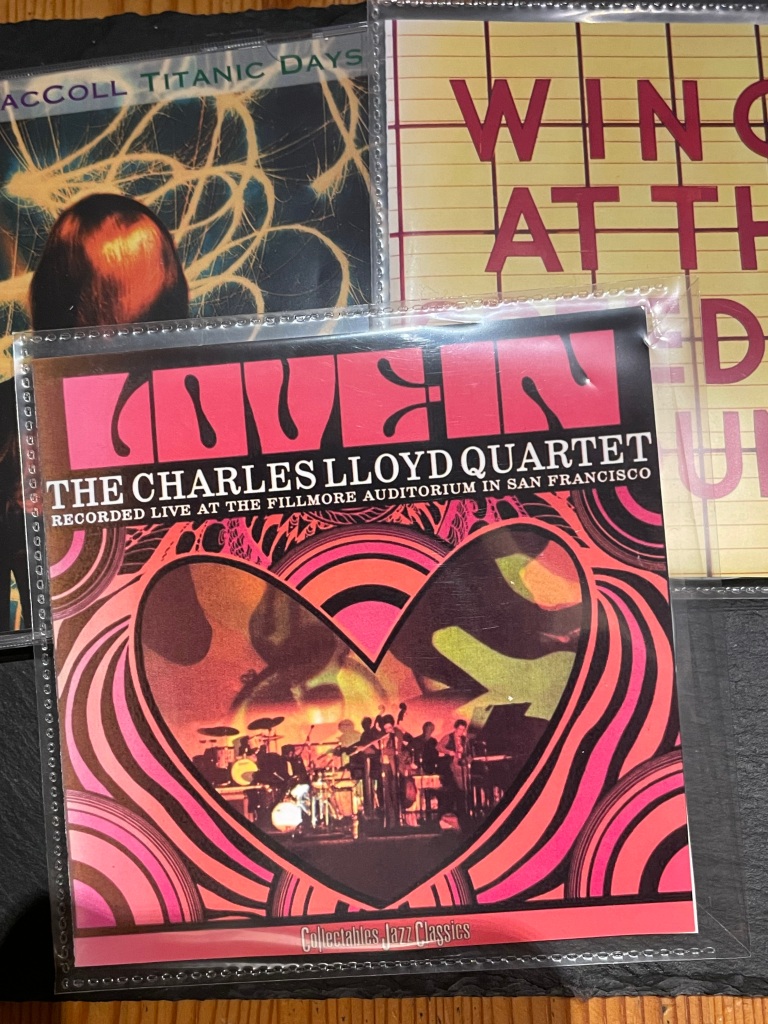

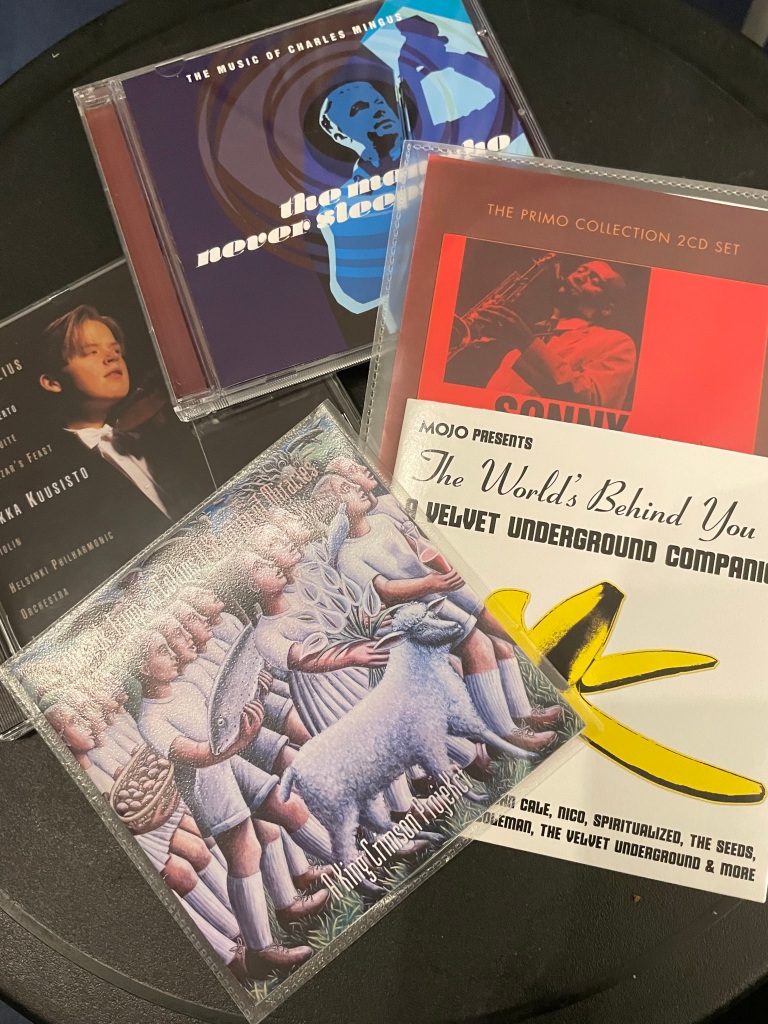

I’ve been trying to build BlueSky as a place to focus my social media if/when X/Twitter becomes too toxic or melts down altogether. So when BookSky featured a challenge to post covers of 20 books that had had a major impact/influence on me, I jumped at it, thinking (rightly) that I might well find amongst the others joining the challenge or responding to my choices people who were worth following, and followed it up with 20 records, and 20 films. (I really, really like lists). The books that I chose are all ones that I’ve talked about on this blog at various times, as are the 20 albums. But I’ve never blogged about my top films. And the BlueSky thing specified no reviews, no details, just the book cover, CD/LP cover or film poster, so here I have a chance to tell everyone not only which 20 films I chose, but why.

This isn’t my stab at picking the 20 best films ever. I could make a case for some of them, but not all. It’s about their impact on me, and that’s subjective, whatever their critical and/or popular standing. I ruled out films where I could not readily recall that first viewing, the when and where of it, but more importantly the feeling of it. Some of these films packed a huge emotional punch, left me wrung out and still sobbing after the credits had rolled. (A lot of these films made me cry – as anyone who has watched a film with me will know, that’s a very low bar – but that isn’t a criterion in itself.) Some of them immediately intrigued me, made me want to watch them again (and again) to figure them out, to understand some of the layers of meaning. In some of them (and these aren’t mutually exclusive categories) the look or the sound of the film (not necessarily the music) were a huge part of their power. But all of these films stayed with me from that first viewing, not only as I made my way home from the cinema, or off to the kitchen to get a cup of tea, but long after. And all but the most recent have proved that they sustain their power on subsequent rewatches.

Of course, making any such list, as those who are addicted to list-making know, is about what you leave out as well as what you include. To get it to 20 meant rejecting films that I love, and that felt bad. I could easily pick another 20 wonderful films, but they wouldn’t quite meet my stringent self-imposed criteria. So these (in no particular order) are the ones that survived the cull, and I’ll tell you why.

Arrival (2016, dir. Denis Villeneuve)

A pretty much perfect film. It has everything one might want from a ‘first contact’ sci-fi movie but then more, much more, than one might expect. The search for a way of communicating is clever and thought-provoking, but also very moving (it reminded me of my favourite Star Trek: Next Gen episode, ‘Darmok’). And the final part of the film – I can’t say anything too specific because if you haven’t seen it, then you need to, and whilst it stands up to any number of rewatchings, the moment on a first watching when one grasps what it is that has happened is so powerful that it should not be compromised. It’s all visually stunning too. The score is one of Johann Johannson’s best, and that’s saying a lot. It’s worth reading too the short story on which the film is based, Ted Chiang’s ‘The Story of Your Life’.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1946, dir. Frank Capra); Music – Dimitri Tiomkin

I resisted this for years. I’d seen it described as ‘heartwarming’, which is a red flag for me – I don’t mind my heart being warmed, but I resent a film/book explicitly setting out to warm it. But when I eventually succumbed and watched it, I found that whilst the very final scene did, indeed, warm my heart, that sentimentality had been more than earned. Capra’s hero is a good man, without any doubt, but we see him tormented by regrets, and by resentment that doing the right thing, as he must, ties him down and traps him in domesticity and small-town life, when he longed and longs to travel the world. He’s angry, and that anger shows. He’s a good man, but not a saint. And so we can identify with his frustration, his regret, even the anger. I always watch this film a few days before Christmas – that became a tradition as soon as I’d watched it that first time – and each time I weep at the opening sequence, as the prayers for George go up to the heavens, and keep weeping, off and on, until The End. There are odd moments at which I wince every time (I hate the way they all patronise Annie, most particularly, and I’m not entirely reconciled to Mary’s transformation into a scared of her own shadow spinster in Pottersville, though there are ways of interpreting this). It’s not a perfect film, in other words, but it’s a powerful and profound one, that goes to very dark places but shows the way out of them. See, if you’re interested, my two previous blog posts about IAWL: You are now in Bedford Falls | Passing Time, Letting it get to you: Doctor Who and George Bailey | Passing Time

Le Mepris (196 , Jean-Luc Godard); Music – Georges Delarue

I don’t tend to love Godard – give me Resnais (see below), Truffaut or Malle any day if we’re talking Nouvelle Vague. But while I was doing a part-time French Language & Cultures degree, which had a very strong cinematic bent, we had a module on intertextuality and studied this particular film in depth. It’s absolutely rammed with intertextual references – the very presence of Fritz Lang, the film posters in the scenes at Cinecento, the books that the characters read, the Odyssey… My enjoyment of the film is more purely intellectual than for most of the films in this list, but no less powerful for that. One can analyse – and we did – every shot, for its use of colour, its framing, its intertextual details, but also the plot, which has layers of ambiguity that keep one pondering. It’s visually very striking, and that strange house – the Casa Malaparte on Capri island – is quite disturbing (I had a strong sense of vertigo when I watched the film on the big screen).

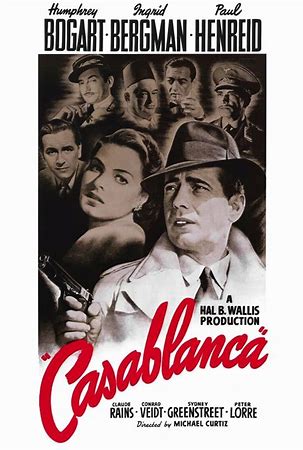

Casablanca (1942, Michael Curtiz); Music – Max Steiner

I loved Casablanca from the first time I saw it (how could one not?). Bogart, Rains and Bergman. The Marseillaise scene. The dialogue, crackling with dry wit. And somehow, that film gets richer and stronger every time I watch it. When I first realised just how many of the people involved in the film – both behind and in front of the camera – were refugees from Nazi Europe, that brought a depth to many of the scenes that I hadn’t realised on first watching. It’s not just the big names (Conrad Veidt, Peter Lorre, Paul Henreid), or the second-tier cast (e.g. Curt Bois, Madeleine Lebeau, S Z Sokall) – the couple earnestly practising their English for their hoped-for new life in the USA, Frau and Herr Leuchtag, were both played by Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany/Austria (Ilka Gruning and Ludwig Stossel). One can love the film without knowing any of this – it’s a pretty much perfect film however one looks at it. The Marseillaise scene always reduced me to sobs, but knowing that Madeleine Lebeau, who plays Yvonne, had had to flee Paris ahead of the Nazis, and that her tears (and those of many of the other cast and crew in that scene) were real and heartfelt, makes it utterly compelling. The film Curtiz provides fascinating background to the director and the production of Casablanca and is well worth seeing.

Last Year at Marienbad (Alain Resnais); Music – Francis Seyrig

I wrote a whole blog about this film. So I won’t repeat myself, other than to say that Alain Resnais is probably my favourite Nouvelle Vague film director, and that one of the things I like about him as that whilst the films he made in the 50s and 60s were enigmatic, heavily intertextual, non-linear, intellectual, he went on to make more comedies, including a number of films of Alan Ayckbourn plays (e.g. Coeurs (Private Fears in Public Places) and Smoking/No Smoking (Intimate Exchanges), much more accessible but still clever and thoughtful. In Marienbad, one of the quintessential new wave movies, there’s a moment when one can see, briefly, the unmistakable silhouette of Alfred Hitchcock (I didn’t believe that when I read about it, but it’s there, I promise – what it tells us is another question). And Resnais, apparently, was a big fan of Marvel, and wanted to work with Stan Lee. Again, I’m not joking. And that leads us neatly on to…

The Avengers (2012, Joss Whedon); Music – Alan Silvestri

The first in a stunning sequence of superhero movies that came to a powerful climax with Endgame. This one has everything that one might wish for from a superhero movie – massive battles, superb CGI, gorgeous superheroes, and a clever, witty script. That final element is courtesy of Joss Whedon, who – though we did not know it then – is highly problematic. But at the time this was released, I was a huge fan primarily because of Buffy, and his script here brings not just humour but depth to the story. Whedon didn’t continue to play much of a part in the Marvel glory years, but he set the tone. I had no background with the comics (graphic novels, whatever), so came to these characters fresh and fell for them. I wrote a blog about Marvel too…

West Side Story (1961, Robert Wise); Music – Leonard Bernstein

I love the Spielberg version – it seems to me that it honours the original without being afraid to change things about it. But for the purposes of this list, it is the original movie that I’m going back to, because the impact of that, on first and on every subsequent viewing, was so great. The choreography is mesmerising, the songs are glorious, the ending is so powerful – that moment when Tony’s guys try to lift his body, and stumble a little, and the others come to take his weight. I can write about it but I can’t talk about it without choking up. It is the finest musical ever (I’m aware that other fine musicals are available, but this just tops everything else).

Girlhood (2014, Celine Sciamma); Music – Para One

Celine Sciamma is probably my favourite current French film director. This is the first film of hers that I saw, and it is gripping, moving, powerful, from the opening sequence. The Roger Ebert site reviewer says: ‘There are many moments that linger in the mind long after the film has ended. The epic slo-mo all-female football game of the opening. An early scene showing a raucous group of girls heading back to the projects, all talking at once, until they fall into silence, collectively, when they approach a group of boys lounging on the steps…’. And I would add the scene where the group of girls try on shoplifted dresses, in a motel room, miming to Rihanna’s ‘Diamonds’… The film is desperately sad, but there’s beauty here too, and humour, and just a smidge of hope. A tough watch but eminently worth it – and I also love Petite Maman and Portrait of a Lady on Fire.

ET (1982, Steven Spielberg); Music – John Williams

Possibly Spielberg’s best. It has his trademarks – the child’s viewpoint, mirrored by an adult who hasn’t forgotten, the sense of wonder, the humour and the sense of loss. I cried through much of this when we first saw it in the cinema (I was not alone in that, as became evident when the lights went up), and cried so much when I first tried to watch it with the children that I thoroughly put them off the film for quite some time. But there’s so much joy in this film – I love the scene where ET gets tipsy at the house, and Elliott picks up his inebriation telepathically, and most of all the moment when the bikes take flight… Having watched The Fabelmans one does tend to read back into Spielberg’s movies from his own childhood, but I don’t think one needs to here – anyone can, whatever their age, if they let themselves, identify with Elliott.

Hidden/Caché (2005, Michael Haneke)

This one has an opening scene which is guaranteed to make cinema audiences start restlessly muttering about whether to alert the cinema staff that something has gone wrong, and home audiences double checking whether their TV or DVD player has frozen. M always quoted this one as the epitome of French film – in his view, a film in which nothing happens, at great length, and with a lot of talking. Which is fair, TBH, but I love it. When things do happen, they hit you with great force, and certain scenes have stayed with me through the years since I saw this at the cinema. It also sparked an interest in a largely forgotten (rather, deliberately hidden) historical event – the massacre of Algerian demonstrators in Paris in 1961. I had never heard of this when it was referred to in the film and found it hard to believe that this could have happened and yet be almost completely unknown. De Gaulle’s censorship was astonishingly effective even outside France and its territories – I discovered when talking to my father that he had heard about the event, but from the newspapers in Ghana where we were living in ’61. I noticed looking at the film’s Wikipedia and IMDB entries that no one is credited with the music – I hadn’t registered the lack of a soundtrack (other than in that opening scene) but it’s intriguing that Haneke chose not to use one. When I next rewatch the film I will be aware of that.

Little Women (2019, Greta Gerwig); Music – Alexandre Desplat

It has to be the Greta Gerwig version. I grew up with the book, identified fiercely with Jo, wept over Beth, and followed them all through to Jo’s Boys and Little Men. I’ve seen various adaptations, on film and TV, over the years, most of which have had something to recommend them, though I recently re-watched the Winona Ryder version and was cross about how girly Jo got about the Prof. But I saw the Gerwig film in very early 2020 and it was a deeply emotional experience. It took me back to the book by deconstructing the book’s chronology and leaned fully into the trope of Jo being both the author and the subject and the two not being identical. But more than that – in early 2020 I knew that very soon I would be losing my little brother, who had been diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2018, and whose journey was very close to the end. So those scenes with Jo and Beth broke me and do so still. It’s another film that I watch every Christmas – even though this version doesn’t open with Christmas – and at the same time that its depictions of family and the closeness of siblings is terribly sad when one has gone (we were four, until we were three, just like the March family), the glorious chaos of four siblings close in age and different in temperament, all talking across one another, squabbling and making up and holding each other close is joyful too.

Timbuktu (2014, Abderrahmane Sissako); Music – Amine Bouhafa

Having seen Sissako’s earlier film, Bamako, a remarkable and fascinating exploration of globalisation through the device of a trial taking place in the courtyard of a home in Mali’s capital, I caught this one at the cinema as soon as it came to Sheffield. It’s about the occupation of Timbuktu by extreme Islamist group Ansar Dine, who impose harsh laws (banning music, making women cover their bodies and even their hands, banning football). Set against this is the story of a small family based outside the city, making a living from their livestock. Sissako shows moments of resistance – the imam who rebukes the occupiers for entering the mosque without removing their shoes, the boys who carry on playing football after their ball is confiscated (a lovely sequence, in which it is very easy to forget that there is no ball, as they swerve and tackle and shoot). Like Bamako, the film is partly about language – we hear Arabic, French, Tamasheq, Bambara and English, and this is linked to the notion of justice as a man is tried for murder in a language he cannot understand. It’s a powerful, tough, beautiful and witty film – and it’s complex too, making the invaders human rather than merely monstrous. The Guardian reviewer said that Sissako ‘finds something more than simple outrage and horror, however understandable and necessary those reactions are. He gives us a complex depiction of the kind you don’t get on the nightly TV news, even trying to get inside the heads and hearts of the aggressors themselves. And all this has moral authority for being expressed with such grace and care. His film is a cry from the heart about bigotry, arrogance and violence.’

The Gospel according to Matthew (1964, Pier Paolo Pasolini); Music – Luis Enriquez Bacalov, inc. Gloria (Missa Luba), Bach, Odetta, Blind Willie Johnson, Kol Nidre

An Italian neo-realist take on Matthew’s version of Jesus’ story, with non-professional actors. It tells the story as Matthew presents it – full of the miraculous. Nothing is added – even the dialogue all comes from the Gospel. Pasolini was hardly the most likely prospect for such a film, given that he was a gay Marxist atheist, but as he said, ‘If I had reconstructed Christ’s history as it actually was, I would not have made a religious film, since I am not a believer. I do not think Christ was God’s son. I would have made a positivist or Marxist … However, I did not want to do that, I am not interested in profanations: that is just a fashion I loathe, it is petit bourgeois. I want to consecrate things again, because that is possible, I want to re-mythologize them.’ The end result is beautiful, strange, remarkable. The soundtrack draws on sacred/religious music from various cultures and introduced me to the Missa Luba, the ‘Gloria’ from which gave me goosebumps when I heard it in the film.

All of us Strangers (2023, Andrew Haigh); Music – Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch

The Guardian described this as ‘a raw and potent piece of storytelling that grabs you by the heart and doesn’t let go.’ I’d read reviews before watching but I wasn’t ready for the way the film handled Adam’s visits to his parents, let alone for the ending. It somehow tapped into my own sense of loss (my parents – one gone, one lost in dementia – my younger brother, my husband). I will watch it again some day to appreciate it fully, but it will be some time before I’m ready.

Last of the Mohicans (1992, Michael Mann); Music – Trevor Jones/Randy Edelman

From that opening sequence, with Day-Lewis running through the woods (‘like a force of nature’, as one reviewer put it), to the dramatic clifftop climax, it’s tense, violent, incredibly romantic and completely absorbing. I’ll be honest, DDL usually inspires more admiration than adoration from me, but here I was with Cora all the way. The film messes with Fenimore Cooper’s book, and with history, but that’s fine. It doesn’t have grand ambitions – it’s quite an old-fashioned film, but it works wonderfully.

Assault on Precinct 13 (1976, John Carpenter); Music – John Carpenter

The original. Obviously (I include an image below from the remake, which I’ve never seen, but maintain is entirely uncalled for). Absolutely gripping – the action is relentless, and one tends to forget to breathe. The ice cream van sequence is horrifying (and Carpenter apparently said that he would have toned that down if he’d made the film later) but I never felt it was gratuitous. The plot is stripped down to bare bones and all that you really feel whilst watching is that you are in that semi-abandoned police station and that you’re under attack, from an enemy who is not going to give up until either all of them or all of you are dead. Brilliantly done, and you might need a lie down afterwards.

The Best Years of our Lives (1946, William Wyler); Music – Hugo Friedhofer

I’ve seen this a number of times, but not for quite a while so it is overdue a rewatch. After all of the heroics of the war movies, here is a sober, realistic portrayal of what three ordinary men came home to. It doesn’t talk about PTSD – it’s not so much (at least not explicitly) about the impact of what they saw and did out there – it’s about who they are now, how they are not the same as when they enlisted, and how/whether those who loved them then will deal with this new reality. It also shows, with honesty, the sense of purpose and comradeship that these men are missing as they try to find their way in the places that were once most familiar to them. Most famously, Harold Russell’s portrayal of Homer, who’s returned with hooks instead of hands, conveys the hurt and the humiliation of being helpless, the fear of being pitied rather than loved.

Paddington (2014, Paul King); Music – Nick Urata

Both Paddington films are superb. Yes, they’re based on books aimed at young children, and yes, the message is appropriately reassuring – bad things happen to good people but it all comes out right in the end, because there are enough good people to thwart the bad guys. Paddington himself is childlike, in the way he experiences new things, and his assumption that the people he meets are going to be benign, until proven otherwise (Mrs ‘Arris, as portrayed by Lesley Manville, reminded me very much of Paddington). His clarity about right and wrong is childlike in its simplicity but adult in its courage. This first film includes some of the most brilliantly funny slapstick sequences, which – unlike some slapstick – never really wear out their welcome. And poignant moments, reminding us about the reality of the world we live in, where we have arguably forgotten how to treat strangers. I’ve listed the first film because that had the most immediate impact – I wasn’t expecting great things really, just a pleasant and amusing interlude, but I truly loved it. It’s a family film in the best sense of that term – it’s about family as well as being aimed at all the family.

Zone of Interest (Jonathan Glazer); Sound – Mica Levi

There could hardly be a more brutal contrast with the previous film listed. There is no comfort here, not a shred. The sounds that we hear throughout the scenes at the house are sometimes neutral (machinery, trains), sometimes not (screams, gunshots) but we know what is happening on the other side of the garden wall, so we know what those trains mean. And yet, after a while, I found that I had filtered the sounds out, as one does with traffic noise if one lives on a busy road. And that was horrifying too. I have only seen Zone once, and whilst it deserves a rewatch to see the detail that one inevitably misses in a first viewing, I am in no rush. I watched it alone, and am glad that I did, because I wasn’t capable of any kind of conversation afterwards, and whereas sometimes after a disturbing film the return to familiar domesticity is reassuring, after Zone it felt (albeit briefly) wrong. I’ve spent a lot of time considering how one can make fiction (film or literature) about the Holocaust, and indeed whether one should. I’ve concluded that it is possible, and indeed necessary, to do so, but that it is also incredibly risky – it should never, ever, be ‘poignant’ (don’t get me started on that), never (heaven help us) heartwarming. If, as in a recent TV fact-based drama, there is a positive conclusion (We Were the Lucky Ones), survival was not a ‘happy ending’ but a shout of defiance in the face of evil.

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006, Guillermo del Toro); Music – Javier Navarrete

I saw this twice at the cinema, and at least twice since on DVD. It’s visually stunning, magical, terrifying, shocking. Roger Ebert called it ‘one of the greatest of all fantasy films, even though it is anchored so firmly in the reality of war’. There are two realities on the screen here, even if the child at the centre of the narrative is the only one who sees the faun and the Pale Man. This taps into so many fantasy narratives – the child who has access to another world, adjacent to, and at times or in certain places merging with our own, whilst adults are oblivious, preoccupied with their own monsters and nightmares.

P.S. I didn’t make a rule that I could only include one film per director, but that’s how it panned out (honest). There is a preponderance, inevitably, of US and UK films, but also movies from Mali, Mexico, Italy and France. Cinema takes us across continents, and also across the centuries – from the ancient narrative of Matthew’s Gospel to contemporary urban life. It’s satisfying to see that this selection, not by design, illustrates that.

Three Cities – Vienna, Prague, Berlin

Posted in History, Personal, Second World War, The City, Visual Art on August 4, 2024

For most of my life, I’ve been fascinated by cities. My teenage years were spent in a rather ordinary dormitory village but I headed regularly for the nearest proper city (Nottingham) for shopping and football, and the annual Goose Fair. I’d previously lived in Kumasi (Ghana’s second city), and Zaria in the north of Nigeria. When I went off to University I settled in Sheffield where I still live, despite a few years commuting to Manchester, and a very brief period commuting to Leicester. My PhD thesis explored ideas about the city, about navigating and failing to navigate it, about the city as labyrinth, looking particularly at Manchester and Paris. And my idea of a really good holiday would be less likely to involve a beach (though a city that happened to have a beach would be quite appealing), but would definitely involve a lot of walking around in a city with heaps of history and culture.

A few years ago, I started to formulate an idea for such a holiday, encompassing two or three European cities, with as much as possible of the travel being by train. The idea never got very far when everything shut down, and we were barely starting to think again about travelling when M died, very suddenly, early one morning in October 2021. In the shock and grief that followed, I wasn’t really thinking about holidays in any practical way, but it did occur to me early on that they would be a challenge.

I can’t see myself travelling alone for any other than the simplest journeys. I take the train up to Dundee a couple of times a year to stay with friends, but always pick the direct trains, and I know I’ll be met at the station, and I went to Rome alone in December 2022, but was met at the airport, and had family to stay with. My biggest challenge in travelling alone is my highly deficient sense of direction. I got lost in Amsterdam on what should have been at most a ten-minute walk from my hotel to the conference venue – heck, I got lost in Leeds (with a similarly deficient friend) trying to get from the Trinity centre to the Grand Theatre. So the thought of a city break on my own is just too intimidating to contemplate – and of course the idea of getting lost in an unfamiliar city alone is something that triggers the hardwired caution that comes from growing up female. Add to this the fact that I am short and not particularly strong, and struggle with any case larger than a weekend holdall, so often have to rely on the kindness of strangers to get luggage on and off trains.

More than this, the pleasure of such a trip would be so diminished if I had no one to share it with. I’d need a travelling companion, and it would have to be a travelling companion who was (a) taller than me – not a major difficulty, most grown-ups are, (b) gifted with a good sense of direction, and (c) interested in the same sorts of things that I am, including with a high tolerance for WW2 history.

I said something about this dilemma one afternoon, sitting with my offspring, not long after M died. At which point the solution became obvious – my son A is (a) taller than me, (b) has an almost supernatural sense of direction and (c) is as much of a history geek as I am, with a similar interest in WW2. I started turning over in my mind what my ideal destinations would be, and Vienna, Prague and Berlin seemed to present the perfect mix of art, architecture and history, with a lot of WW2 and Holocaust sites to visit.

We started planning in earnest, once I’d checked with him that he wasn’t merely being kind when he agreed to go, but actually liked the idea, and worked out timings, and a wish list of places to go and things to see.

I decided, fairly early on in the planning, that whilst sites associated with the Jewish populations of those cities, and museums and memorials recording the destruction of those populations, were high on my list of places to visit, there would be no concentration camps. If I go back to Prague with more time, I will perhaps take a trip out to Terezín, but it was not a priority on this trip. A had visited Sachsenhausen on an earlier trip to Berlin (with school) but had no desire to go back again. This was the right decision – the history of those Jewish communities was less familiar to me than the history of the camps, and what I wanted was to honour the Jewish history of all three cities, and to see the people behind the statistics, in the Stolpersteine on the pavements, in the names on the battered suitcases from Theresienstadt, in the names painted on the walls of the synagogue.

This is a Holocaust heavy trip. I have been reading about and studying the Holocaust since I first encountered Anne Frank when I was probably around the same age as her, and I believe that if we do not understand it, or at least attempt to, we restrict and distort our understanding of post-war politics, history, art, literature and music, even of humanity. It was a significant thread in my PhD thesis, not just the Holocaust itself but how it can be written about, and I have often wrestled with the question of how – indeed, whether – fiction about the Holocaust can shed light. So, whilst I do totally understand why people would choose not to go to these sites, not to read those books or watch the documentaries, it is important to me to do so, to continue doing so. All that I have read, all that I know, has never desensitised me to its horror and it will never do so – the names and photographs, the individual stories, can and do still punch me in the gut. But I don’t go to these sites to get that gut punch, I go to continue to build my knowledge and understanding – and to pay my respects.

Part of my interest in visiting these three cities was to reflect on how they differ, and in particular how they approach their own WW2 history. Austria has described itself as Hitler’s first victim, but it is of course not quite that simple – there was enormous support for the Nazi party, and a long history of virulent antisemitism in Vienna, that ran alongside the major Jewish influence in culture and the arts as well as in business and politics. Czechoslovakia was, entirely straightforwardly, a victim of Nazi aggression, and Prague’s Holocaust memorial takes the form, most powerfully, of the names of the dead, painted on the walls of a synagogue. Berlin deals with its past – both the Nazi era and the injustices and brutalities of the DDR – with candour and without excuses, and its memorial is not about the Jews of Berlin or of Germany, but all of the murdered Jews of Europe.

This blog isn’t a guide to or a history of any of these cities. It’s an attempt to capture the experience, and my reflections on the experience, to help me remember it in all its richness. And I’ve included some of the research I did after we returned home, to find out, where possible, the stories behind the names on the Stolpersteine and other plaques, because for me this was a vital part of the trip. It is an entirely personal mix of anecdote, history, images and quotations and as such may not be a reliable source for anyone else’s city wandering…

Note: for clarity, I have used Terezín as the name of the Czech town, and Theresienstadt as the name of the Nazi ghetto/concentration camp which was created there. I have tried to be consistent with spellings, but Czech names are often to be found in multiple variants, so some inconsistencies may have slipped through.

VIENNA

We arrived on Monday evening, flew in from Manchester and got a train from the airport to the Hauptbahnhof, from where we just had to cross the road to get to our lovely hotel, Mooons (comfortable and welcoming – we were tired and a bit stressed after we’d checked in, having had a slightly less straightforward journey from the airport than we’d anticipated, and Sven the barman sorted out food and beers for us so we started to chill out and enjoy planning our time). We made the most of our two full days in the city – though there is plenty we didn’t see, buildings that we saw from the outside but didn’t go round, for example – I clocked up 59k steps, 40.5 kms. We managed to find some proper Viennese food – e.g. schnitzel and goulash, and good beer (I went for the darker beers, less lagery).

Tuesday:

From our very modern hotel, we were only a few minutes from the beautiful Belvedere Palace – we walked through the gardens which for me had strong Marienbad vibes (as in Alain Resnais’ French new wave masterpiece, Last Year in Marienbad, a film which has fascinated and haunted me for many years, and which I’ve previously blogged about on this site).

On to the Stadtpark, where we found a rather blingy statue of Strauss, and more tasteful ones of Bruckner and Schubert.

Clockwise: Mooons Hotel, Belvedere Palace, gardens and fountains, Last Year in Marienbad, Strauss statue in the Stadtpark.

Walking by the Danube – here there was graffiti, a lot of it political, e.g. re climate change. In general in Vienna, there was no litter, and an orderliness evident in what happened at pedestrian crossings, where no one walked until they were told to walk. It felt a lot safer than, say, crossing a road in Rome, where one feels as if the only way to ever get across is to walk and hope one isn’t immediately mowed down. (A told me of waiting in vain for the right moment at a crossing point in Rome, and another tourist facing the same dilemma saying cheerily, ‘OK, when in Rome…’ and launching himself into the traffic. The cars and bikes do weave around you but it never even starts to feel safe.)

There are two Jewish museums in Vienna. First up was the Museum Judenplatz, built around the excavated remains of the earliest synagogue in Vienna, destroyed in 1421 by order of Duke Albrecht V. It has a fascinating collection building up a picture of that early Jewish community, and of the exploration of the remains. The Jüdisches Museum nearby continues the story of Vienna’s Jewish population through the centuries. But there is a strange sense of a hiatus – not that the Holocaust is omitted but compared to Prague and Berlin, it is arguably underplayed, the job left to the bleak Whiteread memorial in the Judenplatz. This is a bunker, whose walls are made up of books with spines facing inwards to represent the victims whose names and stories are lost, 65,000 Austrian Jews. The names of the camps and other locations where they were murdered are inscribed around the memorial.

Stolpersteine (Schwedenplatz): Here there are three individual stones, and a plaque in memory of 15 unnamed Jewish women and men who lived here before they were deported and murdered (no details given) by the Nazis. The Stolpersteine commemorate Anna Klein, b. 14 Jan 1885, Josefine Steinhaus, b. 21 May 1884, Helene Steinhaus b. 3 August 1885. Deported to Maly Trostinec 27 May 42, killed 1 June 42. Maly Trostinec/Trostinets, a village near Minsk in Belarus, was not a location I was familiar with. Throughout 1942, Jews from Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia were taken there by train and then shot or gassed in mobile vans. According to Yad Vashem, 65,000 Jews were murdered in one of the nearby pine forests, mostly by shooting, but some estimates are much higher, up to 200,000.

Vienna State Opera (Staatsoper) We’d decided against trying to get tickets for any performance here because (a) cost, (b) I haven’t managed to entirely convert A to opera and (c) we didn’t want to commit an evening. That was the right choice – we walked for miles (see above), and in the evenings just wanted time to chill with some nice Austrian beers and talk over what we’d seen and make our plans for the following day. But the building itself is obviously magnificent. And we had seen inside anyway, in Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation…

Clockwise: Stolpersteine, graffiti by the Danube, Judenplatz, Whiteread Holocaust memorial, the Opera house and nearby street

St Stephen’s Cathedral (Stephansdom). As in Paris, the survival of this and other fine buildings was achieved by a refusal to carry out orders. The City Commandant had ordered the Cathedral to be reduced to rubble, but this was not carried out – unfortunately, as the Red Army entered the city, looters set fire to shops nearby, which spread and damaged the roof and destroyed the 15th century choir stalls. Much was saved, however, and reconstruction began immediately after the war, with a full reopening in April 1952.

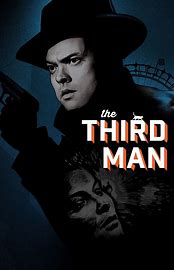

Watching The Third Man makes one realise just how badly Vienna was damaged during the war – not devastated like Berlin, Hamburg, Dresden, but, as Elisabeth de Waal puts it, ‘desultory bombing by over-zealous Americans on the verge of victory, and the vindictive shelling by desperate Germans in the throes of defeat’ had resulted in ‘the gaps in the familiar streets, the heaps of rubble where some well-remembered building had stood’ (The Exiles Return, p. 57). One would not know it now. Clearly, given the fear that rebuilding would destroy the character of the city, the choice was made to rebuild it as it had been, as far as possible. Which gives Vienna that feeling of being preserved in aspic, a slight unreality.

We went a bit further afield, out to Schonbrunn Palace. We didn’t go round the palace itself, preferring to explore the gardens, and head up the hill to the Neptunbrunnen and the Gloriette, to enjoy the view, which was indeed glorious.

Clockwise: Schonbrunn Palace, Gloriette and Neptune fountain; Stephansdom

Maria am Gestade church – one of the oldest churches here, built 1394-1414

Memorial to liberating Soviet soldiers (Heldendenkmal der Roten Armee/Heroes’ Monument of the Red Army), in Schwarzenbergplatz, featuring a twelve-metre figure of a Soviet soldier. This was unveiled in 1945. It seemed to me remarkable that it was built so soon after the war ended, but then I hadn’t realised either that Vienna was liberated by the Red Army, or that in the hiatus before the other Allied Forces arrived, there was a real possibility of Stalin occupying all of Vienna. The memorial is about heroism in battle, not about the violence, particularly sexual violence, inflicted on civilians during and after the battle, and has been controversial and subject to vandalism over the years, including very recently in response to the invasion of the Ukraine.

Wednesday:

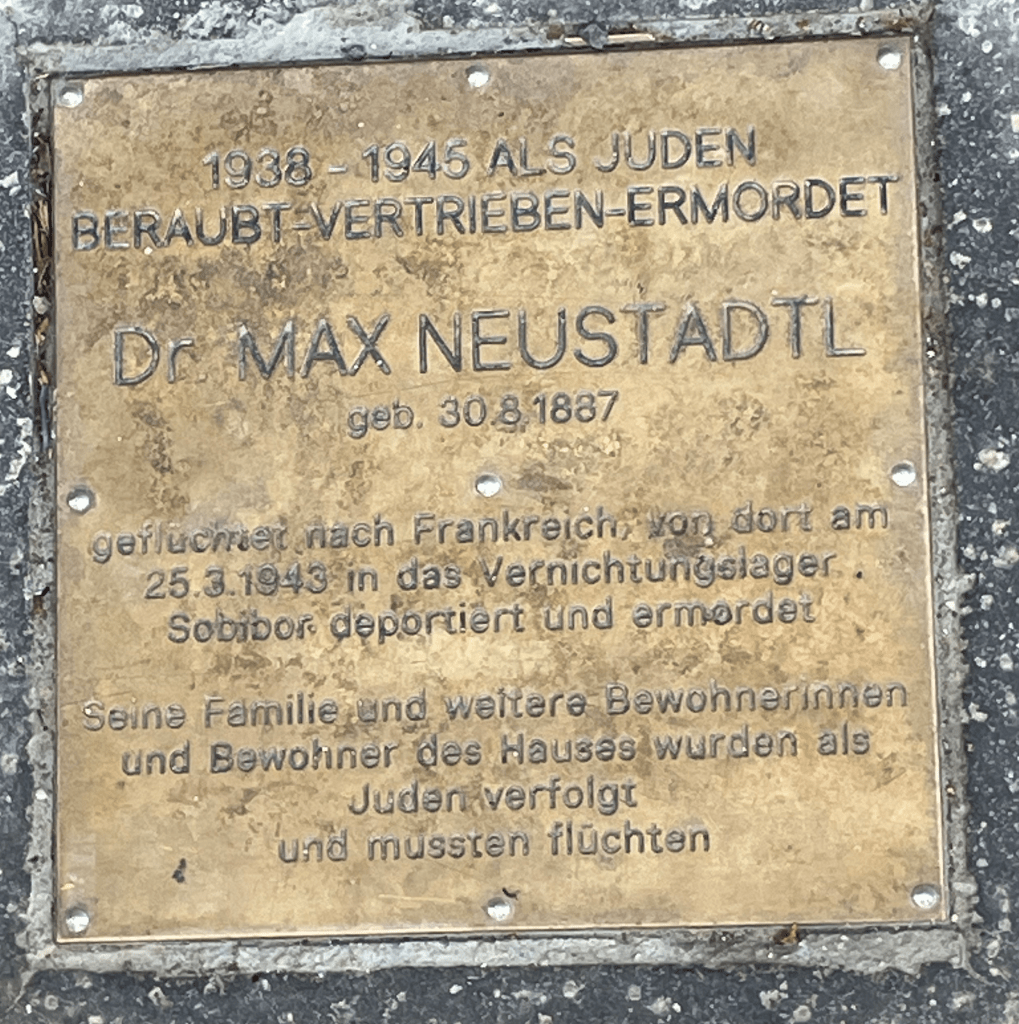

Stolpersteine: Paula Wilhelm (née. Mandl), born 6 April 1887, deported 29 April 44 to Auschwitz; and Dr Max Neustadtl who fled to France but was deported on 25.3.43 to the Sobibor extermination camp and murdered.

Vienna’s second Jewish Museum focuses on the later Jewish communities, covering the period of Nazi rule, but not dealing in great depth or detail with the Holocaust.

One fascinating display here is part of the collection of netsuke whose story is told in Edmund de Waal’s The Hare with the Amber Eyes. These are the Japanese miniature sculptures which belonged to the Ephrussi family, and which were kept out of the hands of the Nazis, unlike most of the contents of the Palais Ephrussi. Six weeks after the Anschluss, the family servant, Anna, was required to pack away the belongings of her former employers. There were lists, of course, to ensure that everything was accounted for. But each time that Anna was in the Baroness’s dressing room, she slipped a few of the netsuke into her apron pocket, and hid them in her room. In December 1945, Anna gave Elisabeth de Waal 264 Japanese netsuke.

‘Each one of these netsuke for Anna is a resistance to the sapping of memory. Each one carried out is a resistance against the news, a story recalled, a future held on to.’ (Edmund de Waal – The Hare with the Amber Eyes, pp. 277-83)

Clockwise: Stolperstein for Max Neustadtl, netsuke in the Jewish museum, Maria am Gestade church, stolperstein for Paula Wilhelm, Heroes Monument of the Red Army

A plaque on Herminengasse gives the names of Jews who lived here, in what was once part of the Jewish ghetto. Many Viennese Jews were forced to live here, until they were deported to various killing sites. Several were killed in Izbica (a town in Eastern Poland, which was turned into a ghetto) – all show the same date of death, 5 December 1942, when the inhabitants of the ghetto (Polish Jews, and those deported from Germany and Austria) were murdered. Those who escaped this massacre were deported again, to Treblinka, Maly Trostinec, Łódź Ghetto, Riga Ghetto, Theresienstadt, Sobibor, Stutthof. I know nothing about these people, other than their age, and where they were killed. But I can see that Oskar Koritschoner was only 20 years old when he committed suicide. Maly Trostinec was the place where 13-year-old Regine Frimet and 3-year-old Ernst Elias Sandor were murdered. And Josef Weitzmann, the last of these to die, was killed in Stutthof concentration camp, in 1944, just after the facilities for mass murder had been set up there. He was 18.

We found the Palais Ephrussi, on the Ringstrasse (see, again, The Hare with the Amber Eyes). I had had an insight into the efforts to trace the plundered contents of the Palais, from Veronika Rudorfer who I met in December 2019 at a conference, when she gave a talk on that project, and subsequently, very generously, sent me a copy of her beautiful book about the Palais itself.

The Burg Theatre – Sarah Gainham’s excellent novel Night Falls on the City has a lot of the action taking place at the Burg theatre, as her protagonist is one of its leading actors. One wouldn’t know that this building was largely destroyed in bombing raids during WW2, and then by a fire subsequently, and has been rebuilt.

Votivkirche (Votive Church) is a gorgeous, somehow delicate looking church, one of the most beautiful in a city of beautiful churches. It is in a neo-Gothic style and was built to thank God for the Emperor Franz Joseph’s survival of an assassination attempt in 1853.

Clockwise: Burg Theatre, Herminengasse plaque, Palais Ephrussi, Votivkirche

We saw the Rathaus – Vienna City Hall – and walked through the Burggarten where we found a statue of Mozart. Then the Resselpark (Karlsplatz), where we saw Sarah Ortmeyer and Karl Kolbitz’s 2023 memorial for homosexuals persecuted by the Nazis: ‘Arcus – Shadow of a Rainbow’, the colours of the rainbow changed to grey, combining grief and hope. There’s also a Brahms statue here, which I like very much.

On to Heldenplatz (Heroes Square), in front of the Hofburg Palace.

‘The two over lifesize equestrian statues on high pedestals are what give it its name, two great military commanders on rearing horses with flowing manes and tails in the Baroque style, one carrying Prince Eugene of Savoy and the other the Archduke Charles, brother of the first Emperor Francis who, in one victorious battle, had stemmed for a while Napoleon’s advance on Vienna. … And yet, with all their panache, there is so little boastfulness in this square. What first meets the eye and impresses the mind are the broad avenues of chestnut trees lining it on three sides … They give the square its peaceful, almost countrified look; they are conducive to slow perambulation and quiet contemplation.’ (Elisabeth de Waal – The Exiles Return, p. 227)

In sharp contrast to the above description, this is where Hitler made his announcement of the Anschluss after his triumphant arrival in the city.

Clockwise: Brahms statue in Resselpark, Heldenplatz, Mozart statue, Rathaus, Arcus memorial in Resselpark

Parliament Building – another building that was seriously damaged in WW2 and the restored to its former glory. In front of it is the Pallas Athene Fountain – apart from Athene (statuary in Vienna is often Graeco-Roman in subject matter and style) it represents the four major rivers, the Danube, Inn, Elbe and Vltava (Moldau in German).

Hofburg Imperial Palace – the official residence and workplace of the President.

Schwarzenberg Monument, commemorating Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg’s victory at the battle of Leipzig in 1813. Yet another equestrian statue (I cannot help it if the Bonzo Dog Doodah Band come to mind when I see these).

Here comes the Equestrian Statue

Prancing up and down the square

Little old ladies stop ‘n’ say

“Well, I declare!”Once a month on a Friday there’s a man

With a mop and bucket in his hand

To him it’s just another working day

So he whistles as he rubs and scrubs away(hooray)

(Bonzo Dog Doodah Band, ‘The Equestrian Statue’ (N. Innes), Gorilla, 1967)

Haus der Musik (Klangmuseum – museum of music and sound) is in the Palace of Archduke Charles, where the founder of the Vienna Phil lived around 150 years ago. The focus is on composers for whom Vienna was significant, with interesting material on Beethoven, Schubert, Mozart, Mahler, Schoenberg and others (not just biographical), as well as fun stuff about the science of music, my first encounter with a virtual reality headset (I didn’t do very well).

Clockwise: Haus der Musik, Archduke Charles monument, Hofburg palace (official residence and workplace of the President), Pallas Athene fountain, Parliament Building, Schwarzenberg monument

Kunsthistorisches Museum – in a palace (of course), purpose built by Emperor Franz Joseph 1 to house the rooms full of antiquities, sculpture and decorative arts. But the highlight was the picture galleries, and especially the Breughels, an absolute joy to see ‘Hunters in the Snow’ etc close up. Also paintings by van Eyck, Raphael, Durer, Holbein, Titian, Caravaggio…

What did we miss? Well, if I went back, I’d go to see the Klimts in the Belvedere gallery, I’d book a tour of the Opera House, and the Parliament building. Might even go on the Riesenrad (I think given the particular form my vertigo takes – see below – I would be OK with it, after all, I was fine on the London Eye).

Vienna Reading: Fiction: Sarah Gainham – Night Falls on the City/Private Worlds; Elisabeth de Waal – The Exiles Return. Non-fiction: Clive James – ‘Vienna’, in Cultural Amnesia; Edmund de Waal – The Hare with the Amber Eyes; Claudio Magris – Danube; Stefan Zweig – The World of Yesterday

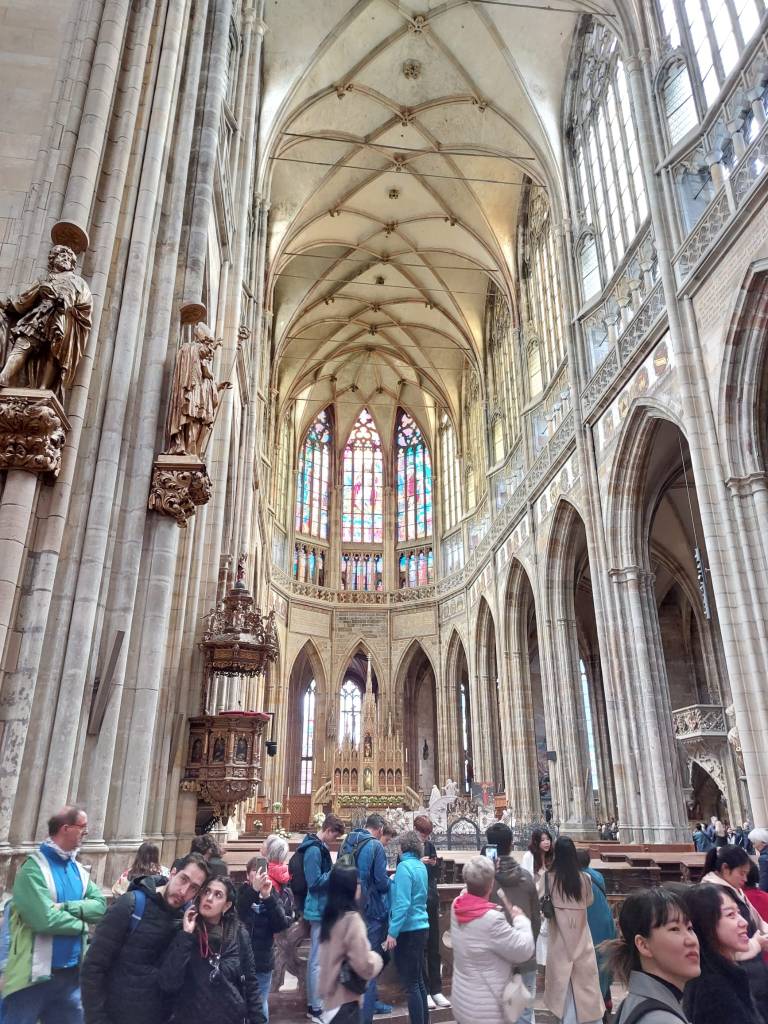

Vienna on Film: The Third Man; Before Sunrise; Vienna Blood (TV detective series set in turn of the century (19th-20th) Vienna)