Posts Tagged Nigeria

Dad

Posted by cathannabel in Personal on June 16, 2025

John Hallett, 26 December 1927 – 30 March 2025

Trying to sum up anyone’s 97 years of life in a not unreadably long blog post is a challenge. In the case of my Dad, John Hallett, who died on 30 March, it’s impossible. As a friend put it, at the celebration we held for his life, he packed at least two lifetimes into those 97 years. And each time I talk or write about him, someone reminds me of some other project, activity or passion that I’d forgotten, or never even known about. He set the bar very high for us all – whatever I’ve achieved in my life seems small beer in comparison – and he wasn’t always very good at telling us how proud he was of us (this was a generational thing, and certainly learned from his parents), though we know he said it to others. My niece had the poignant experience of hearing her grandad, who no longer recognised her, telling her about his lovely granddaughter and great-grandson and how proud he was of them. Most importantly, we knew, always, that we were loved, and that our parents’ love was not conditional upon us achieving things, and that gave us the freedom to be who we wanted to be, who we were meant to be.

John’s early life was pretty conventional – his father was a civil servant who’d fought in the first war, and was an active member of the Home Guard in the second. They lived in Thornton Heath, where Dad was born in 1927, and then moved to North Harrow with his two younger siblings. As a young teenager during the War, he enjoyed the excitement of spotting aircraft and watching the searchlights to cheer as German planes were shot down, until one of his schoolfriends was killed along with their family during the Blitz – a sobering experience. This did not, however, dampen his enthusiasm for aircraft, and the first stage of his career was in aircraft design.

John took up an apprenticeship at de Havillands, leaving school against the wishes of his father, who had wanted his eldest son to follow him into a stable career in the civil service, and he stayed there for four years after the apprenticeship, working in the Design Office.

He left de Havillands because, as a Christian pacifist, he could not countenance working on military projects, and he had begun to think of a future as a teacher, inspired by people he knew and admired. He trained at Westminster College, and then took up his first teaching post at Chatham Technical College (teaching technical drawing, maths, and RE). By then he was married to Cecily, who was to be his strength and his stay until her death in 1995. They’d known each other for a long time, through church, but only gradually came to realise that their friendship was blossoming into love. They lived at 24 Blaker Avenue, in Rochester, Kent. I was born in a Chatham hospital in 1957, Aidan and Claire were born at home in 1958 and 1960 respectively.

The faith that he and Cecily shared was fundamental to their lives, and whilst I do not share their faith, I do share so many of their values, their political beliefs and their approach to what is important about life. They were pacifists, members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation. They were passionately anti-apartheid (many of their ‘expatriate’ colleagues in West Africa at least considered moving on to South Africa or Rhodesia when Nigeria imploded into civil war, but that idea was anathema to them). I learned from a very early age about the slave trade, visiting forts along the Ghanaian coast where slaves had been held before being transported across the Atlantic, and was aware of civil rights struggles in the US and anti-apartheid activism in South Africa and Rhodesia – political issues of the day were a staple of discussion around the dining table each evening. They were socialists, staunch Labour voters. And they were concerned about the environment long before it was the norm.

They both became interested in the idea of working in West Africa, in one of the newly independent nations, but realised that John would need a University degree to teach there. So he did A levels at a local technical college and then enrolled at City University in London, on a scheme designed for those who had been unable to study to degree level during the war years, and obtained a First in Physics and Maths. John was studying part-time alongside his teaching post, whilst Cecily managed the home in Rochester, and brought up the children. John’s father Dennis, a deeply conservative man, never came to terms with the plan to work in West Africa (or ‘darkest Africa’, as he consistently called it), and when we returned home on leave, John had to wait until his father had left the room before talking to his mother about our experiences there.

The family flew out to Ghana in 1960 (with three children, of whom I am the eldest, then aged 3), and a new home on Asuogya Road, on the campus of Kwame Nkrumah University of Science & Technology in Kumasi. Their fourth child, Greg, was born in Kumasi in 1962. John hadn’t had a conventional route to University teaching, and used to comment that he’d arrived as a lecturer having never attended University before – he also often felt that he was only one lecture ahead of his students.

Both John and Cecily became involved in the life of the University, particularly in chamber music concerts. Cecily was an accomplished pianist, and Arthur Humphrey, a colleague, friend and honorary grandparent, played the spinet and recorders. They also held more informal musical evenings, which John’s colleagues and students from the University regularly attended. John preached regularly (both he and Cecily were Methodist lay preachers) at small village churches outside Kumasi, one of which presented (and robed) him in a splendid kente cloth on his last visit. We still have the cloth, somewhat faded and a little damaged after all these years, but still a beautiful reminder of the life we had in Ghana.

He taught Physics and Maths at KNUST but became increasingly interested in pedagogy, rather than in the research aspect of his subjects (despite pressure from his Head of Department – he resisted the idea of, as he put it, knowing more and more about less and less), and was an examiner for the West African Exam Council, and Chief Examiner for O level (the latter involved him designing practical tests which could be carried out in any school, and visiting schools to assess whether they had the necessary apparatus). He was involved with the Ghana Association of Science Teachers, and wrote a Physics O level textbook tailored to the resources available in West African schools and to the experiences of the students, which remained in print for many years.

This growing interest in education per se led him to take up a post at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Northern Nigeria and the family moved there in January 1966. I don’t recall the first part of our journey (by sea from Tema to Lagos) but vividly remember the 600 mile train ride from Lagos to Zaria. The timing of our move turned out to be most inauspicious, as a series of coups and counter-coups rocked the region, and massacres of Igbo people took place in May and September of that year in the area where we lived. We were not in danger at this stage – the violence was very precisely targeted at Igbo people – but of course it was traumatic for the adults to witness what was happening, often to people they knew, and they kept as much of this from us as possible.

The only incident that I recall was when a group of men approached our house, and Cecily and a neighbour took all of the children upstairs and put a record of children’s songs on, whilst John and the neighbour’s husband went outside to speak to them. Strangely, in my memory the men were carrying sticks, but in reality, as I discovered much later, they had machetes. They turned away from our house, but went on to kill a number of people nearby.

I remember being aware of conversations between the adults that stopped abruptly when they realised I was within earshot, but it was not until my teenage years when I pieced together the fragments to understand what had been happening, and this was formative. There is one particularly powerful story that I discovered from talking to my parents and visitors who had been in Nigeria with us. Opposite our house was an unoccupied bungalow, in which we used to play sometimes. I recall being forbidden to do so – snakes were mentioned and I needed no other deterrent. In reality, John had discovered a couple of young Igbo men hiding there. He got them into the family car, covered in blankets, and drove them to the army base, where it was hoped they would be safe. Meanwhile a friend who worked for the railways commandeered a train to take Igbo refugees south to safety, and these two young men joined that group. Tragically, the train was deliberately derailed, and they and others who were fleeing the pogroms were murdered. On both of these occasions, John felt that he had to at least try to intervene. I have often wondered how he felt as he approached the armed men outside our house, and how Cecily felt, knowing what he was doing. And how he felt as he drove those young men to what he hoped might be sanctuary, knowing that if the car was stopped and searched, they would be killed, and he might be in danger too. I don’t know, because he never spoke of these events in personal terms. I believe he felt that he had no choice but to act as he did, whatever the risk.

As I learned about these events, which had happened around me, without my knowledge or understanding, I found I needed to understand the wider issues, and this lead me to read widely about Partition, the Holocaust and the Rwandan genocide.

The family returned home on leave in the summer of 1967, but the worsening situation meant that Cecily and the children could not return, and John travelled back to Zaria alone, to complete his contract, returning to the UK in Easter 1968. We did visit him at Christmas, a rather nervy visit given the volatility of the situation and the presence of armed (but barely trained) soldiers around the city.

Someone once asked me if I blamed my parents for taking us to West Africa, a question that utterly baffled me. On the contrary, I’m in awe of their courage in taking that step, and very grateful for it too. We gained so much – on our return to the UK our horizons were so much wider than those of our contemporaries, and whilst that meant we had a lot of catching up to do on popular culture and so on, it gave us a different perspective, and I think a more generous one. Certainly those years – and the culture of talking about politics and ethics and religion in our home – informed each of us in our developing views about all of those things as we grew older. We would not be the people we are, had our childhood been spent in England.

Cecily and the children were living in the family house in Rochester, and places were found for us at the local primary schools, but on John’s return he took up a post in the Education department at Trent Polytechnic, where he would remain until his retirement. He and I found a temporary home with one of his old friends (a fellow member of the ‘Brew Club’ at Westminster College), so that he could start at Trent, and I could start at Queen Elizabeth’s Girls’ Grammar School in Mansfield. The rest of the family moved up to Nottinghamshire once our new home in Ravenshead was completed.

Whilst at Trent, John was involved in innovative initiatives such as the generalist Education degree and the Anglesey project, worked with VSO to train volunteers for their overseas service, and also took up every opportunity to travel with the British Council or under the auspices of the Polytechnic to visit schools and educational projects in Nepal, Kenya, and the USA. In addition, John was very concerned with the environment, and published, with Brian Harvey, an economist, a well-received textbook on Environment and Society in 1977.

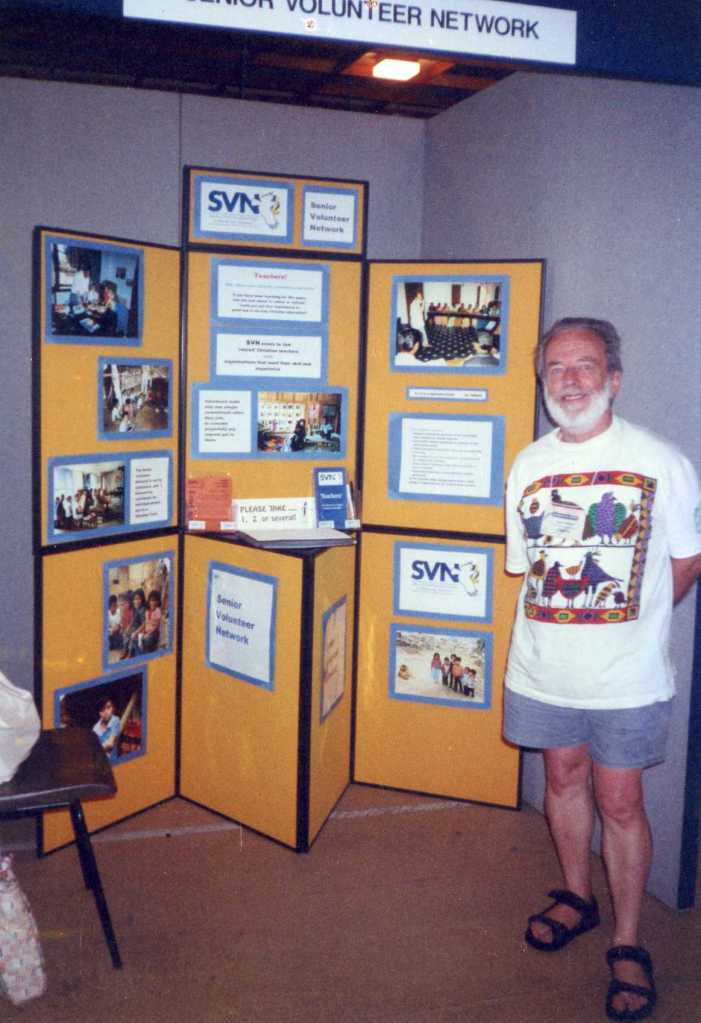

He retired (by then he was Head of the Education Department) in 1987, aged 60, but rather than leading a quieter life, he had a vision for a charity, Senior Volunteer Network, which would put retired teachers/head teachers and other education specialists into projects worldwide, and began to turn this into a reality.

He and Cecily made the most of the freedoms of his retirement (she had retired from primary school teaching some years previously). They both became involved in leadership of the Ravenshead Christian fellowship, which later became Ashwood Church (now based in Kirkby in Ashfield). In the early days of the Fellowship, we met in members’ homes or in the Village Hall. John and Cecily held open house on Sunday afternoons for young people in the village (50 years on, people still talk about how the house was full, every seat taken, and every window ledge and the stairs too) – their home in Ravenshead was called Akwaaba, which in the Twi language spoken in the part of Ghana where we had lived, means ‘welcome’. Part of our parents’ joint legacy to us is the idea of family as an open, welcoming place that embraces new members, whether related by blood, law or none of the above. In West Africa we were a long way from our aunts, uncles and grandparents, and so we accumulated a number of aunts and uncles, friends of my parents who visited regularly, and who I still think of as ‘Aunty Betty’ (with whom I still exchange Christmas cards), ‘Uncle Arthur’, or ‘Uncle Rex’. And in Ravenshead that took the form of opening our doors to random teenagers, some of whom became part of the church (and still are), others who never did, but had reason to be grateful for our parents’ warmth and support, as well as for the Sunday afternoon tea.

As keen walkers, John and Cecily led youth hostelling expeditions to the Lake District, one of which memorably involved Cecily’s group of walkers requiring the Mountain Rescue Service, after getting lost on Great Gable in driving rain and mist. John’s group had taken what was expected to be the more challenging route, only to find when they got to the hostel that we had not yet arrived. They called at the Mountain Rescue centre, at roughly the time that two of Cecily’s party arrived, having been sent out as envoys whilst we huddled behind a rock for (minimal) shelter, and gave their account to the team, enabling them to find their way straight to us.

John was a governor at a number of local schools, volunteered with Mansfield Samaritans (Cecily was a founder member of this branch), and was involved in local politics. He ran regularly, and completed the London Marathon, aged 63, in 1990 – he’d been a keen runner as a young man (plenty of stamina, less speed, due to his short stature), which had taken its toll on his knees and he had to have two knee replacements later in life. He undertook many walks with Cecily (and their dog, Corrie) after his retirement, including the Coast to Coast Walk, and along the Northumbrian coast. Having visited Nepal during his work with Trent Polytechnic, he returned to Everest to climb as far as the snow line, fulfilling his dream to stand on its slopes.

In 1995 Cecily died of pancreatic cancer, aged 65, only a matter of weeks after the diagnosis. It was a huge shock, and an incalculable loss to John and to the family – and to so many more people, as we all discovered from the messages that flooded in after her death. She saw herself as an accompanist – in musical terms this means that she wasn’t there to do the virtuoso solo stuff, but to enhance the performance of other musicians – but she did far more than that, and could have done so much more (at the time of her death she was gaining qualifications in counselling, and working with a Nottingham homeless charity). At the events celebrating Dad’s life, so many people talked not just about John but about ‘John and Cec’. They had different, and complementary strengths, they were a partnership in every sense, and their legacy is a shared one, for us and for the many other people with whom they worked and worshipped.

When Cecily died, SVN was still an idea rather than a reality, and in the aftermath he threw himself into setting up and leading the network, sending volunteers around the world, and travelling himself until his eyesight began to fail due to macular degeneration. SVN still thrives, and the family still has links with it, through Claire who is now a trustee.

John remained active until his 90s, undertaking a skydive to celebrate his 90th birthday, but his sight loss was by then significantly restricting his activities as he could no longer drive, or use the computer. The pandemic shrank his horizons significantly, particularly since he could not easily compensate for the loss of face-to-face social activity with on-line due to his deteriorating sight. In 2020, just before the first lockdown, his youngest son Greg died of bowel cancer, a desperately heavy blow. The death of my husband Martyn in 2021 was also a major shock to him. In 2022 he was formally diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and the decline from that point on was fairly rapid. He was cared for at home by Claire until he needed residential care, and moved into Lound Hall Care Home, near Retford, in 2023.

During those last years, as the fog engulfed him and he became more dependent on others, it was sometimes hard to remember the man he had been. He was a man of bold decisions – leaving school to work at de Havillands, against his father’s wishes, leaving de Havillands on a matter of principle, training as a teacher and undertaking a part-time degree whilst working, taking his young family to West Africa (again, a decision of which his father profoundly disapproved), and then changing direction again to focus on education, and finally setting up SVN in his retirement and travelling to often remote and dangerous places to work on educational projects. He was a leader, from his days as a Cub and Scout where he progressed from ‘Sixer’ to Assistant Scout Master, to his final post as Head of the Education Department at Trent and his role in the church. We all remember family walking holidays when Dad would lead the way so confidently that we all had to rush to keep up, as he was the one with the maps and the refreshments… At the care home, he often, when we visited in the early days, told us that he was there to conduct a review or an investigation, or that we were all at a conference that he had organised. That lifetime of leadership kept a hold even when so much else had been lost.

He had, from a young age, a sense of purpose, and one of his frustrations as his eyesight began to fail was that so many projects – travel abroad, or even ambitious UK walks like the ones that he and Cecily had done years before – were no longer practical or safe. For a while, writing his memoirs became his purpose, although in the final stages of the project dementia had begun to rob him not only of his memories but of understanding, and so I edited the document and arranged publication so that a copy could be placed into his hands whilst he could still recognise it as The Book, his own work.

John was fascinated by the natural world, greatly enjoying finding out about the flora and fauna – particularly the birds – of the parts of West Africa where we lived, and David Attenborough’s documentaries were a source of pleasure and interest in his last years. He read widely, and not only for professional purposes, and turned to audio-books after his sight loss, through which he enjoyed re-‘reading’ Dickens, Trollope, le Carré, Graham Greene and others, as well as discovering new writers (he was particularly enthralled by The Book Thief). He greatly admired the work of C P Snow, a scientist as well as a writer, who explored the idea of the two cultures, science and the arts (Snow’s novels were sadly not available in audio form). He loved music – as a young man he listened to jazz (New Orleans, and Django Reinhardt, not swing, as he told me firmly), but then was converted wholeheartedly to classical music after hearing Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos. Even in the very last stages of his illness he seemed to find calm in listening to Bach and Mozart in particular.

Just over a year ago, I wrote about Dad’s dementia, and specifically about Dad’s ‘raging against the loss of dignity, the loss of control over where he is and what happens to him, against the loss – even if he can no longer articulate it – of the things that made him him, against the slow dying of the light.’ And I expressed our heartfelt wish that his last days should not be spent ‘burning and raving at close of day’. In the end, at the very end, he did ‘go gentle into that good night’, with staff from his wonderful care home taking turns to sit through the night with him. We’re grateful for that, and that we each had the chance to say goodbye, to kiss him on his forehead and tell him that we loved him.

John is survived by his children Catherine, Aidan and Claire (youngest son Greg died of cancer in 2020), daughters-in-law Julie and Ruth, grandchildren Matthew, Arthur, Jordan, Melanie, Vivien and Dominic, step-grandson Tom, and great-grandchildren Jackson, Jesse and Eliza. He will be remembered with love by all of us.

Refugee World Cup, Friday 22 June

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 22, 2018

Playing today: Nigeria, Brazil, Serbia, Switzerland, Costa Rica, Iceland

Nigeria

In 2018, the Nigerian refugee crisis is into its fifth year. Since extreme violent attacks of the Islamist sect Boko Haram spilled over the borders of north-eastern Nigeria into neighboring countries in 2014, Cameroon, Chad and Niger got drawn into a devastating regional conflict. To date, the Lake Chad Basin region is grappling with a complex humanitarian emergency. Some 2.2 million people are uprooted, including over 1.7 million internally displaced (IDPs) in north-eastern Nigeria, over 482,000 IDPs in Cameroon, Chad and Niger and over 203,000 refugees.

The crisis has been exacerbated by conflict-induced food insecurity and severe malnutrition, which have risen to critical levels in all four countries. Despite the efforts of Governments and humanitarian aid in 2017, some 4.5 million people remain food insecure and will depend on assistance. The challenges of protecting the displaced are compounded by a deteriorating security situation as well as socio-economic fragility, with communities in the Sahel region facing chronic poverty, a harsh climate, recurrent epidemics, poor infrastructure and limited access to basic services.

The Nigerian military, together with the Multinational Joint Task Force, have driven extremists from many of the areas they once controlled, but these gains have been overshadowed by an increase of Boko Haram attacks in neighbouring countries. Despite the return of Nigerian IDPs and refugees to accessible areas, the crisis remains acute.

Boko Haram may be the primary cause of flight from Nigeria but it is not the only current factor. In twelve northern states, Shari’a law imposes brutal penalties on alcohol consumption, homosexuality, infidelity and theft. More widely across the country, homosexual couples who marry face up to 14 years in prison, witnesses or those who help them ten years. The law punishes the “public show of same-sex amorous relationships directly or indirectly” with ten years in prison, and mandates 10 years in prison for those found guilty of organising, operating or supporting gay clubs, organizations and meetings.

In 1966, Igbo people fled the North after a series of coups and counter-coups led to massacres in Kano, Zaria and other northern cities.

Brazil

According to the Forced Migration Observatory, a new database from the Brazilian think tank Instituto Igarapé, … hundreds of thousands of Brazilians are driven from their homes each year by disasters, development and violent crime. Venezuelans escaping economic crisis at home are also pouring into Brazil. Though neighboring Colombia has born the brunt of this exodus – welcoming as many as 1 million migrants since 2015 – Brazil has seen some 60,000 Venezuelans arrive and numbers are rising fast.

Despite this influx, Brazil’s main migrant problem remains the millions of displaced people already inside its borders. This domestic crisis has mostly simmered under the radar for nearly two decades.

Serbia

As a result of the arrival of large numbers of people into southern Europe that accelerated two years ago this month, there are 7,600 refugees in Serbia, according to the UN refugee agency (UNHCR). Most live in 18 state-run asylum centres that provide basic necessities. Many are starting to prepare for the long haul. … Meanwhile, every weekday, five people are chosen to leave Serbia and enter Hungary – and the EU – legally. It may be a double-edged sword. “In Hungary my family are in a 24-hour closed camp – when someone goes to the bathroom there are four police on every side of you,” said Weesa “They are not free like we are here.” Faqirzada says many countries could learn a lot from Serbia. “In Afghanistan, no one cares for each other. In Turkey there were no schools. In Bulgaria we slept in forests. But in Serbia, the people support each other. They support my family too, I do not forget this.” Still, if and when the Faqirzada family are given a chance to move closer to Germany, they will take it.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/08/eu-refugees-serbia-afghanistan-taliban

The Kosovo War caused 862,979 Albanian refugees who were either expelled by Serb forces or fled from the battle front. In addition, several hundreds of thousands were internally displaced, which means that, according to the OSCE, almost 90% of all Albanians were displaced from their homes in Kosovo by June 1999. After the end of the war, Albanians returned, but over 200,000 Serbs, Romani and other non-Albanians fled Kosovo. By the end of 2000, Serbia thus became the host of 700,000 Serb refugees or internally displaced from Kosovo, Croatia and Bosnia.

Switzerland

During World War II, Switzerland as a neutral neighbour was an obvious choice of destination for refugees from Germany and France in particular. Switzerland’s longstanding neutral stance had also involved a pledge to be an asylum for any discriminated groups in Europe – Huguenots who fled from France in the 16th century, and many liberals, socialists and anarchists from all over Europe in the 19th century. However, Swiss border regulations were tightened in order to avoid provoking an invasion by Nazi forces. They did establish internment camps which housed 200,000 refugees, of which 20,000 were Jewish. But the Swiss government taxed the Swiss Jewish community for any Jewish refugees allowed to enter the country. In 1942 alone, over 30,000 Jews were denied entrance into Switzerland.

The closure of the popular migration route via the Balkans border in March 2016, led to a rapid increase in the number of refugees in Switzerland as they immigrated to Germany. Refugees entered Switzerland through Ticino, and a report estimated there were 5,760 illegal residents in this region.

Amnesty International reported that migrants and asylum-seekers with rejected asylum claims were returned in violation of the non-refoulement principle [a fundamental principle of international law that forbids a country receiving asylum seekers from returning them to a country in which they would be in likely danger of persecution based on “race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion]. Concerns remained regarding the use of disproportionate force during the deportation of migrants. Government proposals for the creation of a National Human Rights Institution continued to be criticized for failing to guarantee the Institution’s independence.

Costa Rica

4,471 asylum applications by refugees were received in 2016 in Costa Rica – according to UNHCR. Most of them came from El Salvador, Venezuela and from Colombia. A total of 2,815 decisions were made on initial applications, of which 81 per cent were initially rejected. Violence in El Salvador and Honduras is causing refugees to arrive in increasing numbers.

Because they’re often escaping severe violence in their countries of origin, they often need greater psycho-social assistance to address mental health needs. A lack of local support networks means they require more material and economic assistance than other groups, too.

As in other contexts, refugees in Costa Rica face barriers that prevent them from fully exercising their rights: discrimination, xenophobia, and a lack of information (either on their side or from the host community). Unlike many places hosting displaced populations, however, refugees and asylum seekers in Costa Rica have the right to work, start their own businesses, open bank accounts, and access public services (health care, education, etc.). Understanding this context is critical to counteracting barriers, easing local integration, and increasing self-reliance. UNHCR identifies individuals and families living in the most vulnerable conditions and addresses their immediate needs. Then, to empower households to build new economic and social lives and better integrate into their host countries, they’re included in the Graduation program.

To encourage this integration and address extreme poverty faced by Costa Rican households, several women from local communities are included in the project. Most are survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, single mothers in highly vulnerable conditions, or HIV positive. Not only does this provide vulnerable women from Costa Rica with a pathway out of poverty, it also enhances the self-reliance and community integration of refugee women and children by connecting them to a similarly vulnerable local community of women.

Since Iceland’s refugee policy was first initiated in 1956, the country has accepted a grand total of 584 refugees, a rate lower than other Nordic countries. Groups and families of refugees have arrived from a diverse range of countries — Vietnam, Poland, Hungary, former Yugoslavia and Serbia. Post-recession, Iceland’s economy has recovered at a four percent growth rate per year. However, according to a PBS report, Iceland would require 2,000 new immigrants a year to maintain that level of growth — refugees would contribute to this number. The Mayor of Akureyri, Eirikur Bjorgvinsson, explains that refugees contribute more to Iceland’s economy than the amount of assistance that they are actually receiving. In order to become assimilated in Iceland society, the government offers financial assistance, education, health services, housing, furniture and a telephone for up to one year to refugees in Iceland. According to the Ministry of Welfare, the policy in Iceland has welcomed a quota of 25 to 30 refugees every year. However, this quota has changed in the last few years with the crisis in Syria, protests from Icelandic citizens and an exception in 1999 with the outbreak of the war in Kosovo.

In the next few weeks 52 new refugees are expected to arrive to Iceland, as reported by Vísir.is. Most of them are children and young adults under the age of 24. Last August, the Icelandic government agreed to welcome 55 refugees. As we reported last year, however, a Market and Media Research poll on the subject showed that 88.5% of Icelanders believe the government should welcome more of them.

The 52 refugees who are on their way to Iceland are mostly of Syrian, Iraqi and Ugandan origin. While the Syrian and Iraqi have lately been residing in refugee camps in Jordania, those coming from Uganda were forced to seek asylum away from their home country because of their non-normative sexuality (Iceland has been accepting queer refugees since 2015).

Upon arrival they will be sent to different parts of the country: 4 families are going to the Fjarðabyggð municipality in the east, 5 families to the Westfjords peninsula in the North and 10 individuals will stay in Mosfellsbær, close to Reykjavik.

The Minister of Social Affairs Ásmundur Einar Dádason assured that the preparations to receive the refugees are in full swing. “The results have been positive so far and we received applications from the municipalities to participate in the program,” he said. “It’s a very good example of a solid partnership between the state, the local authorities and the Red Cross.”

https://grapevine.is/news/2018/02/09/52-refugees-on-their-way-to-iceland/

Refugee Week 2017 – reflections

Posted by cathannabel in Refugees on June 25, 2017

We’re living in strange times. Last year’s Refugee Week took place in the aftermath of Jo Cox’s murder, and midway through, we found out the outcome of the EU referendum, which for so many of us, perhaps falsely reassured by the predominance of Remain sympathies in our social media bubbles, was profoundly shocking, as well as filling us with dismay and fear about the future. Our world was further shaken in November by the outcome of the US election – again, we were unprepared for a Trump victory, and fearful of the impact it would have – we still are, although straightforward incompetence and inefficiency seem to have mitigated some of the potential harm so far.

This week Refugee Week takes place in the aftermath of terrorist attacks which have claimed innocent lives in Manchester, on Westminster and London bridges, in Borough Market and Finsbury Park. And then there’s Grenfell Tower, a human tragedy of unbearable proportions. That’s not even to mention a General Election and the start of the Brexit talks.

This time last year I wrote these words, which are still pertinent:

I said a week ago when I started my annual Refugee Week blogathon that it felt different this year. As Refugee Week draws to a close it feels unimaginably different again. We are in, as so many people said during the long hours as the result of the referendum emerged, uncharted territory. We are in uncertain times.

For refugees and asylum seekers there is no charted territory, there are no certain times. But as anecdotal evidence mounts of racism and xenophobia seemingly legitimised and emboldened by the vote to leave the EU, as we wait for those who would lead us into this brave new world to give us a clue as to what it will be like, I know I am not alone in being afraid. … But many of us do share the belief that how we treat people who seek sanctuary from war, persecution and starvation is a measure of what kind of country we are, what kind of people we are. And many of us do believe that generosity, empathy, compassion are qualities that represent the best that we can be, individually and collectively.

So as this Refugee Week ends we will be continuing to say that refugees are welcome, saying it louder if we need to, if the voices against us are more numerous or more vociferous.

I’ve returned this year to some of the themes I regularly write about. I’ve revisited the work of Cara with at-risk academics, for example, prompted by my own University’s engagement with their current campaigns and its funding of scholarships and fellowships for refugee academics and students. I’ve talked again about child refugees – remembering the Kindertransport in light of this government’s shameful reneging on the Dubs amendment.

I’ve tried to celebrate the work of so many superb organisations, large and small, who are working to support refugees around the world and here in the UK, addressing the politics and the practicalities, making a huge difference against the odds.

Each year I approach this entirely self-imposed task – to post every day during Refugee Week about some aspect of the crisis faced by so many millions of people forced to flee their homes – with a certain amount of trepidation. Who do I think I am, really, to speak about these things? I’m no expert, I’m merely a keyboard activist, I have no direct personal experience of the things I write about. And who am I writing for? Preaching to the choir, surely, given that my readers, my social media contacts, by and large are people who share my world view.

But as much as I berate myself for hubris in taking the task on, I cannot relinquish it. I write, that’s what I do. I use this blog to talk to whoever might be listening – and if I change no one’s mind, perhaps the information and ideas and links that I gather for each piece will be useful to someone else, somewhere along that chain of communication that we build as we share and retweet – about the things I care about and the things that trouble and grieve me. And this issue is something I care about, passionately.

Perhaps it is personal, after all. My first Refugee Week blogathon recalled events which, even though I cannot claim to have directly witnessed them, or even to truly remember them, still shaped me:

Nigeria, 1966

During the series of coups and counter coups leading up to the secession of Biafra and the Nigerian Civil War, thousands of Igbo people were killed in the northern territories of Nigeria. Many more fled to escape the massacres. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie‘s Half of a Yellow Sun gives a harrowing account both of the pogroms and of that flight, from a number of perspectives – the Igbo heroine, in Kano as violence explodes, who escapes on a train along with many others, traumatised, lost and bereaved; the Englishman who finds himself at Kano airport as Igbo staff and travellers are identified and killed; the people meeting the trains as they arrived, searching for their own friends and family afraid to find them and not to find them.

As I read her account, I found myself shaking and weeping. I lived in the north of Nigeria at this time. I was a young child, 9 years old, and my parents shielded me and my younger siblings from as much as they could. But I knew that people were being killed because of their ethnicity. I saw the mob which approached our home looking for Igbos, knew that my father and a friend had gone out to speak to them, to try to calm them and deter them but without success. I knew of westerners arriving at Kano airport, to witness scenes of horror, some of whom got back on the plane as Richard does in the novel. I learned later of the people who my parents found hiding in the unoccupied house across the road from us, who my father took in the back of our car, covered with blankets, to the army compound where others had taken refuge, and of the train organised by another expatriate to take them all to safety but which was ambushed, its passengers dragged out and killed.

As a teenager I pieced these stories together, from the recollections that my parents were finally willing to share without holding back, and the fragmentary memories that I did have suddenly made sense. And I’ve been piecing it together ever since, as I see the people who fled from the town I lived in over and over again, in the faces of those seeking refuge from war and persecution today, as I see them in the faces of those who fled war and persecution generations ago.

And once you do that, you become aware of the connections, of the way in which everything that is happening around the world is interlinked.

As Daesh suffer military defeats and the loss of their territory, they increase their terrorist attacks in the west but far more often in the Middle East and Africa, killing ‘Crusaders’ but far more often Muslims who happen to be the wrong sort of Muslim. And as one of the major forces creating refugees, they are also used as a reason to mistrust those very refugees. Because, so they say, they could have pretended to be refugees, paid a fortune to traffickers, risked drowning in the Med, lived on minimal rations in a refugee camp, simply in order to launch attacks in European cities… The uncomfortable truth, that attacks in European cities have been carried out by long-term residents of those cities, isn’t allowed to disturb the anti-refugee narrative, and the call in the wake of every attack for borders to be closed, etc.

The first officially confirmed casualty of the Grenfell Tower disaster was Mohammad Alhajali, a refugee from Syria, who had survived civil war and the perilous journey to the UK, only to die in his own home as a result of an accidental fire and the criminal neglect of fire safety in social housing.

And we learned that one reason for the difficulty and delays in identifying the dead, or even coming up with a reliable total of those who perished, was that there may well have been people living in Grenfell Tower who were ‘off the radar’, worried about their immigration status, unable to afford their own accommodation and so unofficially staying with friends or family but not on any list of tenants. People like asylum seekers (those waiting for a decision, and those who have been refused), and those newly granted refugee status who have not yet got the paperwork together to get a place of their own. Grenfell Tower sheds a harsh light on so many aspects of our society – the calls for a ‘bonfire of red tape’, the mockery of ‘health & safety gone mad’, the contempt of the wealthy and privileged for those on the margins – the culture of ‘us and them’.

I think of this, from a rather wonderful Twitter account:

“I am a citizen of the world.““Citizen of nowhere. You must pick an ‘us’ to be.”“I did.”“All humanity? Nonsense. That leaves no ‘them’.”

There is no us and them. It’s us and us. It’s all us.

That really is the heart of it all. We can refuse the ‘us and them’, we can assert that it’s all us. It’s the only way to be human, really.

Nigeria, 1966/World Refugee Day, 20 June 2012

Posted by cathannabel in Genocide, Refugees on June 20, 2012

Nigeria, 1966

During the series of coups and counter coups leading up to the secession of Biafra and the Nigerian Civil War, thousands of Igbo people were killed in the northern territories of Nigeria. Many more fled to escape the massacres. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie‘s Half of a Yellow Sun gives a harrowing account both of the pogroms and of that flight, from a number of perspectives – the Igbo heroine, in Kano as violence explodes, who escapes on a train along with many others, traumatised, lost and bereaved; the Englishman who finds himself at Kano airport as Igbo staff and travellers are identified and killed; the people meeting the trains as they arrived, searching for their own friends and family afraid to find them and not to find them.

As I read her account, I found myself shaking and weeping. I lived in the north of Nigeria at this time. I was a young child, 9 years old, and my parents shielded me and my younger siblings from as much as they could. But I knew that people were being killed because of their ethnicity. I saw the mob which approached our home looking for Igbos, knew that my father and a friend had gone out to speak to them, to try to calm them and deter them but without success. I knew of westerners arriving at Kano airport, to witness scenes of horror, some of whom got back on the plane as Richard does in the novel. I learned later of the people who my parents found hiding in the unoccupied house across the road from us, who my father took in the back of our car, covered with blankets, to the army compound where others had taken refuge, and of the train organised by another expatriate to take them all to safety but which was ambushed, its passengers dragged out and killed.

As Rob Nixon said, in the New York Times, ‘“Half of a Yellow Sun” takes us inside ordinary lives laid waste by the all too ordinary unraveling of nation states. When an acquaintance of Olanna’s turns up at a refugee camp, she notices that “he was thinner and lankier than she remembered and looked as though he would break in two if he sat down abruptly.” It’s a measure of Adichie’s mastery of small things — and of the mess the world is in — that we see that man arrive, in country after country, again and again and again.’

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s literary role model is often said to be Chinua Achebe, who himself was caught up in these events. His writing having brought him to the attention of the military who suspected him of having foreknowledge of the coup, he had to send his pregnant wife and children on a squalid boat through a series of unseen creeks to the Igbo stronghold of Port Harcourt. During the civil war which followed, his family had to move repeatedly to escape the fighting, returning to their destroyed home only after the war was over. His poem, ‘Refugee Mother and Child’, reflects those experiences:

No Madonna and Child could touch

that picture of a mother’s tenderness

for a son she soon will have to forget.

The air was heavy with odors

of diarrhea of unwashed children

with washed-out ribs and dried-up

bottoms struggling in labored

steps behind blown empty bellies.

Most mothers there had long ceased

to care but not this one; she held

a ghost smile between her teeth

and in her eyes the ghost of a mother’s

pride as she combed the rust-colored

hair left on his skull and then –

singing in her eyes – began carefully

to part it… In another life

this would have been a little daily

act of no consequence before his

breakfast and school; now she

did it like putting flowers

on a tiny grave.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Half of a Yellow Sun (London: Fourth Estate, 2009)

Chinua Achebe, Collected Poems (Manchester: Carcanet, 2005)

Rob Nixon, ‘A Biafran Story’, New York Times, 1 October 2006

World Refugee Day, 20 June 2012

http://takeaction.unhcr.org/

di·lem·ma \ : a situation in which a difficult choice has to be made between two or more alternatives, especially ones that are equally undesirable.

No one chooses to be a refugee

Every minute eight people leave everything behind to escape war, persecution or terror.

If conflict threatened your family, what would you do? Stay and risk your lives? Or try to flee, and risk kidnap, rape or torture?

For many refugees the choice is between the horrific or something worse.

What would you do?

World Refugee Day was established by the United Nations to honor the courage, strength and determination of women, men and children who are forced to flee their homes under threat of persecution, conflict and violence.