Posts Tagged music

Music Nights 2024

Posted by cathannabel in Music on December 18, 2024

Last year I tried for the first time to write about the part that music has played in my life, the way in which that is bound up with my relationship with my late husband, and how I struggled with finding ways of listening alone. It will never, of course, be the same, not even close. But I have prioritised listening to music from our collection, as well as listening to Radio 3 as we used to, and have added some new bands, composers and music programmes to my repertoire. I’m proud of that – it wasn’t as easy as it might sound.

Not long into 2024, my hi-fi was dismantled, and my CDs packed into boxes and stored in the garage, ahead of a major redecoration of the living/dining room. It all took a long time, and only now, as the year draws to a close, do I have full access both to the CD collection and to the means of playing them. Now, I do know about streaming and am aware that playing actual CDs marks me out as very old school indeed – and as the list below shows, I did carry on regardless. But I like to hear the whole album, the tracks that the artist decided to record, in the order that they wanted them to appear. And so many of these CDs were acquired and listened to with M, and, as I said in my music blog a year ago, it’s very important to me that this tradition – of evenings devoted to listening to CDs, chosen semi-randomly from the vast collection – is part of my life now.

Music Nights (or mornings, or afternoons, but mainly nights) – the methodology is as described in last year’s blog. During the week if I think of something I’d like to play (it might be suggested by something I’ve read, an anniversary or obituary, or just a memory) I put it on a pile by the CD player, and on the night I add to that pile random choices – whatever came up when I threw the dice and counted the shelves – so that I don’t stay too firmly within familiar territory, or within any one era or genre. This does include music on TV or DVD and tracks that I accessed via Spotify as well as via the collection, but in general inclusion indicates that I listened to more than just a single track, even if not a full album.

This year I listened to music by: Beethoven, Berlioz, black midi, Bombay Bicycle Club, Bowie, Brahms, Britten, Brubeck, Bruckner, R D Burman, Byrd, Alina Bzhezhinska, Camel, Can, Nick Cave, Terri Lynne Carrington, Hariprasad Chaurasia, Chopin, Billy Cobham, Leonard Cohen, Alice Coltrane, John Coltrane, Costello, Kim Cypher, Miles Davis, Olivia Dean, Delarue, Bryce Dessner, Corrie Dick, Marlene Dietrich, The Last Dinner Party, Dinosaur, Dreamliners, Dukas, Dylan, Earth Wind and Fire, Elgar, Ella, Ellington, ELP, Eno, Fairport Convention, Fakear, Fauré, Reinhard Fek, Catrin Finch & Seckou Keita, Graham Fitkin, Fleet Foxes, Flobots, Frankie goes to Hollywood, Marvin Gaye, Gilgamesh, Gomez, Pavel Haas, Charlie Haden & Egberto GIsmonti, Matthew Halsall, Gavin Harrison & O5Ric, P J Harvey, Lianne la Havas, Dashiell Hedayat, Hendrix, Bernard Herrmann, Hindemith, Zakir Hussain, Keith Jarrett, Johann Johannson, Quincy Jones, Quincy Jones & Miles Davis, King Crimson, Michael Kiwanuke, Gideon Klein, Gladys Knight, Korngold, Last Shadow Puppets, Bill Laswell, Ant Law & Alex Hitchcock, Léonin, Los Campesinos, Yo-Yo Ma, Kirsty MacColl, James MacMillan, Mancini, Bob Marley, Maximo Park, Curtis Mayfield, Fanny Mendelssohn, Felix Mendelssohn, Pat Metheny, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Monk, Mozart, Mulligan & Monk, Nick Mulvey, Meshell Ndegeocello, Yoko Ono, Pérotin, Iggy Pop, Psi Vojaci, Rachmaninov, Emma Radicz, Radiohead, Ravel, Red Rum Club, Martha Reeves, Max Richter, Rodrigo y Gabriela, SBB, Ryiuchi Sakamoto, Schoenberg, Schubert, Schumann (Robert & Clara), Semer Ensemble, Shangri-las, Sharp Little Bones, Shostakovich, Sibelius, Silk Road Ensemble, Horace Silver, Nina Simone, Roni Size & Reprazent, Smetana, Sam Smith, Snarky Puppy, Katie Spencer, Spiritualized, Candi Staton, Steely Dan, Max Steiner, Richard Strauss, Karl Svenk, Taylor Swift, Sylvian & Fripp, Tallis, Tangerine Dream, Carlo Taube, Michael Tippett, Peter Tosh, Ali Farka Toure, Travis & Fripp, Martina Trchova, Unthanks, Vaughan Williams, Verdi, Kevin Volans, Weather Report, Yiddish tango

Live Music

Music nights are almost always solitary now. But live music is also vital to me, and for that I often especially value company. So thank you to Ruth, Peter, Adi, Jennie & Michael, Arthur, Jane & Richard, Amanda, Liz and Under the Stars colleagues for sharing some of these musical experiences with me.

Opera

For a few years, I reviewed Opera North productions for The Culture Vulture, a Leeds-based online journal, which was fabulous – I got free tickets to all of the productions. All this came to an end for me even before lockdown, as my youngest brother, who had terminal cancer, approached the end of his life, and I knew I could not commit to attending or to turning a review around within a day. When lockdown ended, I was looking forward to starting again and was due to see Carmen on 9 October 2021. That morning, M died. It was not until my sister-in-law, who had got me started on this whole opera thing, moved back to Leeds from Rome last year that I went back to the Grand Theatre (not as a reviewer, just a regular audience member).

At Leeds Grand we saw two marvellously magical productions, Mozart’s bonkers The Magic Flute, and Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, both of which were delightful, imaginatively staged and beautifully sung. Before that, we saw Britten’s Albert Herring at the Howard Assembly Rooms, a lovely, funny production.

West Yorkshire Playhouse’s revival of My Fair Lady drew on Opera North talents too, with lovely performances in the lead roles, including John Hopkins (a former sidekick of Midsomer Murders’ DI Barnaby) as Henry Higgins, and Katie Bird, who we saw in The Merry Widow back in 2018 at the Grand, as Eliza. It has tricky moments – not so much Higgins’ sexism, given that this is not endorsed by the script or by the production, but the off-hand references to domestic violence, the normality of black eyes and broken bones as part of married life. I can’t recall if these are in the Shaw, or only in the libretto. Despite that it was a gorgeous, funny production and it’s packed with glorious tunes, beautifully sung.

Sheffield City Hall – Legend: The Music of Bob Marley. Excellent tribute band – the lead singer in particular was superb. I wondered about the audience when I saw a lot of white folks wearing knitted hats with knitted dreadlocks attached, but it was clear they were passionate enthusiasts for the music, knew all the lyrics, and kept a respectful silence when asked to do so in memory of Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett. An exuberant evening of fantastic songs.

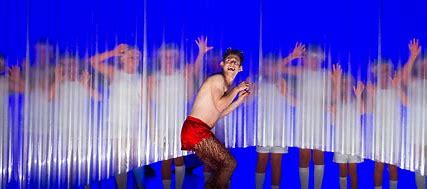

Manchester Palace Theatre – Hamilton. I’d seen it on Disney+ but live is so much better. Spinetinglingly, exhilaratingly great songs and singers, superb choreography, a compelling story. It probably shouldn’t work but it absolutely does and I loved every moment.

Since I got involved with Under the Stars, first as a trustee, now as Chair, I aim to get to as many of their gigs and drama performances as I can. It’s always a joy. This year, Sparkle Sistaz played the Octagon Centre at Sheffield University as part of a Street Choirs event and went down a storm (they were followed by the excellent Young ‘Uns, who recognised they had a damn hard act to follow). The Stars Band played at Yellow Arch and at Tramlines, and Clubland Detectives launched their new EP with a gig at the Greystones Pub.

Music in the Round is always a huge part of my musical year. It started off with a concert in the Upper Chapel (Koechlin, Tomasi, Lutoslawski, Poulenc) and then the Steven Isserlis curated Chamber Music Festival in mid-May celebrated Fauré’s centenary with a packed week of gigs, mainly at the Crucible Playhouse. I got to five of the concerts, and heard music by Ades, Bach, Farrenc, Faure, Franck, Holmes, Messager, Onslow, Ravel, Saint Saens and Tchaikovsky, performed by Ensemble 360, with Isserlis, Peter Hill, Abbeydale Singers, Ella Taylor and Anna Huntley. And then Kathy Stott launched the autumn season with a performance of short pieces by Bach, Boulanger, Ravel, Piazzola, Shostakovich, Rodgers & Hammerstein, Chopin, Fitkin, Shaw, Vine, Grainger, and Grieg. This was part of her farewell tour, with a programme of short pieces – it was wonderfully eclectic and delightful.

We were at the Crookes Social Club for Sheffield Jazz gigs from the Clark Tracy Quintet, Corrie Dick Sun Swells, Hannah Horton Quartet, Adam Glasser, and Soft Machine, the Crucible Playhouse for Empirical with Jason Rebello, Firth Hall for Fergus McCreadie, and the main Crucible Theatre for their 50th anniversary gig, with the Emma Rawicz Quartet and the Tony Kofi Quartet. All were excellent but standouts were Corrie Dicks, Soft Machine and Tony Kofi.

This year’s Tramlines was dry and sunny, for which we were very thankful after last year’s downpour and resulting quagmire. The stand-out performances were from Maximo Park, Dylan John Thomas, The Human League, Sprints and Stars Band. We also saw Bombay Bicycle Club, Coach Party, Example, Flowerovlove, Darla Jade, Jazzy, Miles Kane, Otis Mensah, Harriet Rose, Mitch Santiago, Rumbi Tauro and The View plus brief snippets of The Charlatans, Cucamaras and Paolo Nutini.

And then a new feature on Sheffield’s musical calendar, Richard Hawley’s Rock & Roll Circus – we only went to one of the three nights, but enjoyed Gilbert O’Sullivan, The Coral, The Divine Comedy and Richard Hawley himself. O’Sullivan I remember fondly from the 1970s, when he had a run of hits, all of which he performed here and most of whose lyrics I could recall. His voice is still there (not always the case with performers whose heyday was 40+ years ago) and it was an enjoyable set, if not one that made me want to seek out his newer material. I fell in love with The Coral years ago – that Mersey/Motown blend is joyous and I love them live (I saw them at Tramlines 2022). I was much less familiar with The Divine Comedy’s output (I knew ‘National Express’ of course but little else) but was inspired to listen to more. And Hawley, in his home town, was electrifying, performing songs that featured in the musical Standing on the Sky’s Edge, which played to rapturous full houses here in Sheffield, and less inevitably, replicated that success in the West End.

And a concert at the tiniest venue I know, Café 9. Pre-booking is essential, and reserving seats helpful as one can end up practically knee to knee with the performers – but it’s a gorgeous space, which I discovered last year, and went to three gigs there in fairly quick succession. Just one this year, from Katie Spencer, whose songs draw on her upbringing on ‘the edge of the land’, as one of her songs puts it, on the East Yorkshire coast. She’s a great songwriter, guitar player and singer. She was supported by Gerard Frain, an excellent South Yorkshire singer-songwriter.

For next year I’m checking out the Sheffield Jazz programme and the 2025 Sheffield Chamber Music Festival programme, I’m already booked to see two operas (Weill and Verdi), and we have our tickets for Tramlines in July. And whatever else the year brings, I know it will be full of music.

2024 Reading – the second half

Posted by cathannabel in Literature on December 6, 2024

My reading this year has been the usual eclectic mix. I normally (normal for me, I hasten to add) have four books on the go at any time. One will be in French, maintaining a fairly recent resolution (so far this half year, de Beauvoir, Gide, Mauriac, Fatou Diome and Francois Emmanuel, of whom the last two were new to me). At least one will be non-fiction. One will be on the Kindle, two will be by my bedside to read before I turn out the light, and one in my library room (currently the French one).

Having brought so many books, half-forgotten in many cases, down from the attic this year, I’m instituting a new ‘rule’ for 2025 – one of the four books will be a re-read. Or, possibly, a first read if it’s one I’ve had for yonks but honestly can’t recall whether or not I did read it (there’s a lot of M’s sci-fi stuff that’s in that category). But there are also books the mere sight of whose covers made me yearn to revisit them. And whilst life is short and there’s so many great new books out there, there are also so many great old books that absolutely deserve to be savoured all over again.

I read a lot of crime fiction, but would not want to be reading more than one in that genre, as clues and corpses could easily get in a muddle. When it comes to crime fiction in particular, I haven’t listed everything I read, not because it wasn’t any good, but because ongoing series are hard to review without just repeating myself about how good, e.g. Elly Griffiths or Val McDermid is.

There are a few books here that slide across genres – Thomas Mullen’s Blind Spots is crime + sci-fi, Leonora Nattrass’ Blue Water is crime + historical fiction. For more straightforward historical fiction the stand-out is Maggie O’Farrell’s The Marriage Portrait. And for books that don’t present us with the world that we know or that existed, or not straightforwardly, there’s Evaristo’s alt history/alt geography Blonde Roots, Mullen, Jenny Erpenbeck’s End of Days which plays around with how death normally operates, and Kate Atkinson’s short stories (see below). I was pleased to discover some new novelists in this batch, notably Nathan Harris, Caleb Azumah Nelson, Margot Singer and Anna Burns – my top books of this half year are Nelson’s Open Water and Burns’ Milkman, and in non-fiction, Paul Besley’s The Search. As always, I try to avoid spoilers, but do proceed with caution.

Fiction

Kate Atkinson – Normal Rules Don’t Apply

I love Atkinson – Life after Life in particular is one of my absolute favourite books. I’m not generally a fan of short stories but these are – as the title suggests – quirky and sometimes baffling, as well as being often very funny, and definitely need to be re-read asap.

Simone de Beauvoir – Les Belles Images

Reading this, I felt as if it should be one of those French films where elegant people sit around talking about ideas, when they’re not sleeping with each other’s partners. Isabelle Huppert should be in this. I’ve not found it an easy read, partly because the narrative voice switches between our protagonist Laurent, and a narrator, without the distinction always being clearly made on the page. It’s short on event (another reason why it should be one of those French films), very introspective. Worth persevering, because it’s intelligent and perceptive and sharp, and the discussions they have are still pertinent fifty years on.

Mark Billingham – The Wrong Hands

The second in his new Declan Miller police procedural series. Miller is infuriating, but funny and human (though I’m not sure he’s quite different enough from Tom Thorne, about whom the same things could be said), and the crime here is woven together with his own search for truth about the death of his wife, which gives it a lot of heart.

Anna Burns – Milkman

I’ve been meaning to read this for a long time – urged on by my Belfast-born sister-in-law in particular – and I’m so glad I did. It’s darkly funny and terribly sad and horrifying and the people in it blaze with individual life, despite not being named.

Candice Carty-Williams – People Person

I loved her debut, Queenie but this didn’t quite work for me. It started off brilliantly, with the crackling dialogue that was so enjoyable in Queenie, and the deft characterisation of the group of half-siblings and their hopeless father. But the event that dictates the rest of the plot and what flowed from it just seemed so improbable, and then it all got resolved rather too neatly. A lot to enjoy along the way but flawed.

Fatou Diome – Le Ventre de l’Atlantique

A Senegalese woman, making a living (just about) in France, talks on the phone to her younger brother who (along with many of his contemporaries) is desperate to make the same journey, with dreams of being a professional footballer. Through their phone conversations and her own account of her life in their village, we explore those dreams and the realities that the dreamers don’t want to face, all with the backdrop of the 2000 European Cup and the 2002 World Cup.

Francois Emmanuel – La Question humaine

I saw the film based on this – Heartbeat Detector, starring Matthieu Amalric – some years ago and it’s pretty close to the book. A psychologist in the HR department of the French branch of a German firm is asked to investigate the fitness of the CEO and finds himself investigating complicity or direct involvement in the Holocaust. At the heart of it is an exploration of language – the inhuman language of memos dating from the early phases of the Holocaust, and the reductive language of HR practice in large corporations.

Jenny Erpenbeck – The End of Days

The structure frequently wrong-footed me at first – characters are unnamed – it’s the daughter, the mother, the grandmother – and so as we move around in the chronology those relationships change too. Worth the effort to focus. The central conceit reminded me of Kate Atkinson’s Life after Life – a life ends, but it need not have, and what if it didn’t end then, but a bit later, or much later than that? Compelling and moving.

Bernardine Evaristo – Blonde Roots

An alternative world, where the slaves are white, their owners African. It’s not a straight reversal of history, geography has been adjusted too. It’s funny – I love the scene where the white peasant family raise the newborn to the heavens to see ‘the only thing greater than you’, a skit on that same scene in Roots, and perhaps on the Lion King too… The Independent said, ‘Running through these pages is not just a feisty, hyperactive imagination asking “what if?”, but the unhealed African heart with the question, “how does it feel?” This is a powerful gesture of fearless thematic ownership by one of the UK’s most unusual and challenging writers’.

Sebastian Faulks – Charlotte Gray

I think I read this slightly too soon after Simon Mawer’s The Girl who fell from the Sky/Tightrope which has a very similar plot (young female SOE agent parachuted into France, but with her own agenda). It was worth reading though, and it avoids the clichés of wartime heroics, with a compelling protagonist. Apparently Faulks received a Bad Sex award for this but honestly, I’ve read far, far worse…

Damon Galgut – The Promise

Across the years, from the ‘80s to 2018, a South African family wrestles with the huge changes in society, and with the titular promise, made on her deathbed by the matriarch Rachel, that the family servant, Salome, would be given a house of her own on the family farm. It’s a promise that’s explicitly disavowed, or deliberately forgotten about, or that simply is impossible to keep, but that promise speaks eloquently about South African society and its history. It’s in four sections, each beginning with the death of a member of the family, and each reflecting key episodes in the country’s recent history. In each section we see things from the perspective of one of the family members, although always with dry asides from the narrator to puncture their naivety or complacency. But the person into whom we get the least insight is Salome, who is more of a symbol than a character, let alone a protagonist.

André Gide – La Porte étroite

The only Gide I’d read before this was Thesée, his version of the story of Theseus and the Minotaur, which I read whilst writing my PhD thesis, and preoccupied with labyrinths. That was published in 1946 – this is a much earlier work, from 1909, and with a strong biographical element, as the central relationship between his protagonist Jerome and Jerome’s cousin Alissa reflects Gide’s relationship with his own cousin, who he married, despite his homosexuality. Here the issue is not so much sexuality – the relationship between Jerome and Alissa is intense but spiritual rather than physical, and mired in misunderstandings and things unspoken.

Patrick Hamilton – Hangover Square

Rather a depressing read, TBH. But bleakly funny at times. The Critic said that ‘This novel could not have been written at any other point in history. Hamilton is a great navigator of human frailty in the face of desolation. It is not the bar room drinkers, but the articulation of the tragic lack of power man has over the madness that swirls about him that makes Hangover Square a novel of its time.’

Nathan Harris – The Sweetness of Water

Set in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Harris’s debut novel tells of a white farmer whose encounter with two newly freed slaves both transforms his life, and brings about tragedy. It’s beautifully written, with the central characters all given depth and complexity. It’s about change, and how even the most desired, necessary, righteous social change is traumatic, and not just for its opponents. It’s about how people – individuals and communities – move on from that, about what freedom might mean at this time and in this place. Deeply moving, and with a sense of hope.

Robert Harris – Archangel

Harris never lets me down. We start off in Death of Stalin territory, and then jump forward to the post-Soviet era to meet our protagonist, an academic specialist in Soviet history who gets embroiled in highly dangerous secrets that show how that great dictator is not and perhaps cannot ever be entirely consigned to history. Thrilling up to the final page.

Sarah Hilary – Sharp Glass

The latest stand-alone psychological thriller from Hilary, and it’s another corker, perhaps her best yet. It’s not about twists for the sake of twists (I do go on a bit about this, but it really annoys me, when all credible plotting or character development is jettisoned for the sake of ‘a twist you’ll never see coming’…). Here, character is all, and these characters gradually become clearer, to themselves, to each other and to the reader, but there are loose ends left loose, not tidied away, so we’re still wondering about the protagonists after we’ve turned the final page.

Winifred Holtby – The Crowded Street

Holtby’s second published novel. I’d read South Riding many years ago, and several times – my Mum was a fan – and also Anderby Wold, but this one was new to me. Her protagonist is a young woman who feels a strong sense of familial duty but nonetheless struggles to fit the role that is expected of her. It’s often funny but there’s a deep sadness too, and anger.

Aldous Huxley – Point Counterpoint

A roman à clef about interwar intellectuals (based on, inter alia, D H Lawrence, Middleton Murry and Huxley himself). Like a fugue, the novel unfolds through a series of different voices and different debates, interweaving and recurring in different forms. As such it’s wordy and light on incident, but nonetheless fascinating.

Tom Kenneally – Fanatic Heart

I was looking forward to this – I’d read a few of Kenneally’s books years back and remember liking them, and Fanatic Heart covers an interesting period of history, spanning three continents, from the Irish Famine through to the first stirrings of civil war in the US, through the life of Irish nationalist writer John Mitchel. But the style was somehow so inert. The story was eventful enough, it should have been engaging but instead it dragged, and I ended up skim reading the last chapter or so just to finish it. The story is also cut off before what would potentially have been an opportunity to explore Mitchel’s controversial views on slavery (he was for it), and his loyalty to the Confederate cause during the Civil War. But I’m afraid I didn’t enjoy this enough to read a sequel, if there is one.

Jhumpa Lahiri – The Namesake

Touching, funny account of a young man’s life, from a Bengali family, growing up with a Russian name in the USA. Julie Myerson in the Guardian said that ‘this is certainly a novel that explores the concepts of cultural identity, of rootlessness, of tradition and familial expectation – as well as the way that names subtly (and not so subtly) alter our perceptions of ourselves – but it’s very much to its credit that it never succumbs to the clichés those themes so often entail. Instead, Lahiri turns it into something both larger and simpler: the story of a man and his family, of his life and hopes, loves and sorrows.’

Francois Mauriac – La Pharisienne

Mauriac’s Le Noeud de Viperes was one of the first French novels that I read (in French) without having to, whilst I was at school. I’ve read several of his other novels, and his remarkable clandestine pseudonymous publication Le Cahier Noir, a rallying call to Resistance during the Occupation. He’s a hero of mine – he was in many ways a conservative – family, the Church, his country – but never an unquestioning one, and his questioning led him to challenge the Church’s support for Franco, and to bring his skill as a writer to the Resistance. He was never going to be a fighter (too old, too weedy), but he still risked everything by his activities and associations. This novel was published during the Occupation, under his own name, because it isn’t, at least overtly, about that. It’s the study of a woman whose religious convictions make her seek perfection not only in herself but in those around her, and to deal harshly with those who fall short. As a critique of religious zeal it was controversial enough – but the depiction of a culture of denunciation perhaps does refer obliquely to the Occupation. It’s powerful and Brigitte Pian, the ‘Woman of the Pharisees’ is a horrifying creation.

Arthur Miller – Focus

I was prompted to re-read this by watching Joseph Losey’s film Mr Klein (see my screen blog). This is Miller’s only novel and it’s premiss is a man who gets a new pair of specs and realises he now looks like a Jew, and that people around him are suddenly seeing him as a Jew. It’s a powerful and shocking account of antisemitism in the US at the end of WWII, and all the more interesting because the protagonist is himself a repository of antisemitic and other racist prejudices (unlike, for example, Gregory Peck’s character in Gentleman’s Agreement, who is noble and righteous and allowing himself to be seen as a Jew consciously and deliberately).

Thomas Mullen – Blind Spots

I have read and loved Mullen’s trilogy (Darktown, Lightning Men and Midnight Atlanta) dealing with Atlanta’s first black cops in the era of segregation and civil rights protests. This is completely different – we’re in an unspecified future, where everyone, worldwide, gradually lost their sight. A technological solution has been found (even if it’s not available, or acceptable, to everyone), downloading visual data directly to people’s brains. But then, it gets hacked, and no one can really trust what they’re seeing… It’s a sci-fi crime thriller, which is completely gripping, but also thoughtful and thought-provoking.

Leonora Natrass – Blue Water

A cracking historical mystery, set in the days of the American Revolutionary Wars, and we’re all at sea, en route to Philadelphia with a disgraced FO clerk, who is trying to ensure that a vital treaty will reach the Americans in time to stop them joining France’s war on Britain. This is the second in a series so I should really have read Black Drop first, but thoroughly enjoyed this one nonetheless and will backtrack to its prequel asap.

Caleb Azumah Nelson – Open Water

Stunning debut from a young British-Ghanaian writer, with a second-person narrative that involves the reader intensely in the protagonist’s thoughts, emotions and experiences. It’s about love, race, masculinity. The i review describes it as ‘an emotionally intelligent and tender tale of first love which examines, with great depth and attention, the intersections of creativity and vulnerability in London – where inhabiting a black body can affect how one is perceived and treated’.

Maggie O’Farrell – The Marriage Portrait

Gorgeously written historical novel, beautiful and tragic and very memorable. Its heroine is Lucrezia de’Medici, married at 15 to the Duke of Ferrara, whose early and suspicious death inspired Robert Browning’s ‘My Last Duchess’.

Ann Patchett – The Dutch House

This almost sounds like a fairy tale – a magical house from which the children are driven out by their stepmother. But for all of the motifs from those archetypal narratives, it’s really about how we deal with the past when the past has hurt us. Maeve (an extraordinary creation) and Danny, the two exiled children, struggle with and find different approaches to this. As the Guardian reviewer put it, Patchett ‘leads us to a truth that feels like life rather than literature’.

Richard Powers – Orfeo

I discovered Powers last year through The Time of our Singing. Like that book, this one is suffused with music. The Independent reviewer said ‘There are passages that make you want to rush to your stereo, or download particular pieces to listen to as you read — Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder, Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time — and others that seem to offer that same experience for pieces you will never hear, pieces composed by Powers’s composer hero, Peter Els.’ It’s not just about the subjective experience of music, it’s about composition, and microbiology and technology, and it’s absolutely compelling.

Margot Singer – Underground Fugue

Another novel that invokes musical form (see also Huxley’s Point Counterpoint). In this case, fugue is both structure – there are four voices here, which alternate and interweave, and connect or echo each other in different ways – and psychological state – all four are exiled and unrooted (and there’s a connection too to the case of the so-called ‘Piano Man’). As these stories interconnect, we move closer to the climactic event of the novel, the 7/7 London bombings. Beautifully written, suffused with a sense of loss.

Cath Staincliffe – The Fells

A police procedural dealing with a cold case – the discovery of a skeleton in some caves in the fells. As always, Staincliffe is interested not just in the crime, and who was responsible for it, but in the ramifications of the crime, the effects on the family and friends. And as always, she makes you believe in her characters, including her new detective duo, and care about them.

Elizabeth Strout – The Burgess Boys/Lucy by the Sea

I do love a Strout. As always, these novels connect with each other, and with others of Strout’s oeuvre. The Burgess brothers connect here to Lucy Barton (via Bob), and we also encounter (indirectly) Olive Kitteridge and the protagonists of Abide with Me – there are more links than those, and I think some kind of a flowchart is called for. Lucy is a Covid novel, it starts with Lucy’s ex-husband William insisting on taking serious steps to isolate the people he cares about as the pandemic looms, and it explores the strange world that we all inhabited then with Strout’s remarkable insight and empathy.

Douglas Stuart – Shuggie Bain

This is a tough read. It’s brilliantly written, with profound sympathies for its characters, including some of the more hopeless ones, but most of all for Shuggie as he tries to survive a chaotic childhood and navigate a path to some kind of stability. There were many moments when I feared how this would end, when a brief period of hope ended in yet another heartbreaking betrayal or failure, but ultimately there is some hope. Just enough.

Kit de Waal – Supporting Cast

These short stories connect to de Waal’s novels – as the title suggests they take characters who played a supporting role in those narratives and bring them to the foreground. As always with de Waal, these people, the lost and the losers, are drawn with tenderness and understanding, and I found them very moving.

Colson Whitehead – Crook Manifesto

A brilliant sequel to Harlem Shuffle. We’re now in the 70s, and furniture salesman Ray Carney is trying to stay on the right side of the law, but things get messy… The writing is marvellous, edgy and with bleak humour. As the Independent says, ‘the blend of violence, sardonic observation and out-and-out comedy reflects Whitehead’s ability to neatly balance the trick of writing both a homage to, and affectionate tease of, noir crime fiction’.

Non-Fiction

Albinia – The Britannias

Alice Albinia takes us island-hopping, and on each of the islands that surround Great Britain, she explores the history (going back to ancient times, and moving gradually forward to our own), folklore, landmarks and traditions, weaving in her own personal history and the conversations she has with locals and fellow-travellers. A lovely, intriguing read.

Paul Besley – The Search: The Life of a Mountain Rescue Dog Search Team

I probably would not have come across this book had I not known its author. And that would have been such a loss. I’m not particularly a dog person – that is, I’ve never lived with a dog, and there are only a few that I have got to know at all well (Alfie, Loki and Bentley). I did have my own encounter with Mountain Rescue though, when I was a teenager with a small group on a church youth hostelling trip who got stuck in awful weather on Great Gable and I can still vividly remember hearing and then seeing our rescuers arrive, with duvet coats and hot chocolate and the relief and joy and gratitude that I felt. The book describes Paul’s own experience of being rescued (a great deal more dramatic than mine) and subsequent involvement with Mountain Rescue, culminating in training a dog, Scout, to work with him to track people who need help in the hills. It’s that training process that forms the bulk of the book, and it’s extraordinary – fascinating and moving and gripping. The title turns out to mean much more than the literal search for those lost bodies – it’s a very personal search for meaning, for a way of living well and in the present, for contentment even in the toughest of times. Do read it, whether or not you are a dog or a hiking person – it’s quite remarkable.

Jarvis Cocker – Good Pop, Bad Pop: An Inventory

Not a memoir. Rather, this is Jarvis rummaging in his attic and telling us stories about some of the stuff he finds there, whilst debating whether to keep or get rid of each item. It’s very engaging, playful and tricksy (just how random are these random items? Were they all actually in that attic at the start of the project? Did the things he tells us he decided to ‘cob’ (a Sheffield word – albeit not one I’m familiar with – for chuck out) actually get cobbed?). And along the way lots of brilliant anecdotes about Jarvis’s youth and the early days of Pulp.

Joan Didion – Blue Nights

I read The Year of Magical Thinking last year, just long enough after the sudden death of my husband. That book deals not only with her husband’s death but with the serious illness of their daughter Quintana, who was in hospital, unconscious when he died, and after an initial recovery became seriously ill again, dying just before Magical Thinking was published. Blue Nights tells – in a non-linear fashion – the story of Quintana’s adoption, her issues with depression and anxiety, her illness and death, through Didion’s eyes. Didion shows, with brutal clarity, how little she understood her daughter, and it offers no healing insights into dealing with such a loss. Cathleen Sohine wrote in the NY Review of Books that ‘Blue Nights is about what happens when there are no more stories we can tell ourselves, no narrative to guide us and make sense out of the chaos, no order, no meaning, no conclusion to the tale’. It’s utterly bleak. Whereas Magical Thinking is an act of mourning, Blue Nights, permeated by Didion’s sense of failure as a mother, and failure to understand Quintana, is a cry of despair.

Jeremy Eichler – Time’s Echo: Music, Memory and the Second World War

Brilliant, fascinating and eminently readable. A study of four composers (Richard Strauss, Schoenberg, Britten and Shostakovich) and a key work by each, responding to World War II and the Holocaust in particular. It generated a powerful playlist: Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw, Strauss’ Metamorphosen, Britten’s War Requiem and Shostakovich’s 13th Symphony (specifically the 1st movement, the Adagio, often referred to as Babi Yar) and along the way lots of other pieces are discussed, with such clarity that one almost feels as if one can hear them.

Paul Fussell – The Great War and Modern Memory

Fascinating study – published in the ‘70s – of how the ‘Great War’ was portrayed in poetry and fiction, how literary references, mythology and religious ideas permeated these portrayals, along with a strong strand of homoeroticism. Some of the work Fussell explores is familiar to me (Owen, Sassoon, Graves), some not at all, but it’s full of interest and new insights. I was particularly struck by how the ‘literariness’ of the accounts was not restricted to the officer class but is present in diary and memoir from other ranks too, suggesting a widespread familiarity with, e.g. Shakespeare and Bunyan.

Rebecca Godfrey – Under the Bridge: The True Story of the Murder of Reena Virk

An insightful account of the murder, carried out by a group of teenagers, of another teenage girl, a bullied outsider. I watched the TV adaptation of this, which oddly makes Godfrey a protagonist, getting directly involved in the investigation, and having a personal history that connects her to the suspects, none of which is actually what happened. It’s odd because it derails the drama, which really needs no embellishment. The book is much better than I was expecting, having been irritated by the dramatization (but sufficiently intrigued to see what the source material actually said).

Richard Holmes – The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science

A rather wonderful account of science in the Romantic era – Herschel and Davy, Mungo Park and Joseph Banks. There are important women here too, most notably Caroline Herschel and Mary Somerville. Very readable, and not just for historians of science – one of the fascinating things about this period is that people weren’t silo’d into arts or sciences as later generations, including my own, tended to be – William Herschel was a composer and Humphrey Davy a poet.

Stuart Jones (ed.) – Manchester Minds: A University History of Ideas

Full disclosure – I contributed a small ‘vignette’ to this volume, on W G Sebald and Michel Butor. But there’s masses of interest here, all marking the 200th birthday of the University of Manchester by celebrating some of its most notable and influential figures. I was drawn to the outsiders or exiles amongst them – like economist W Arthur Lewis, from St Lucia, Gilbert Gadoffre whose time at the University was interrupted by a spell of activity in the French Resistance, Eva Gore Booth, the Irish poet and activist, and philosopher Dorothy Emmett, plus a number of Jewish academics who had left Europe either because of pogroms in the East, or the advent of the Nazis.

Hilary Mantel – A Memoir of my Former Self

A collection of Mantel’s short non-fiction, on a wide range of topics, some autobiographical (these overlap with Giving up the Ghost, a memoir that she published in 2010), some film and book reviews, and most enjoyably and interestingly her Reith lectures on writing historical fiction. As in her novels, she is sharp, funny, and sometimes fierce – her account of how her endometriosis was dismissed by a series of doctors as just female neurosis is utterly enraging.

D. Quentin Miller (ed.) – James Baldwin in Context

A collection of short essays on aspects of Baldwin, his life, his novels, his politics. I’ve immersed myself in Baldwin periodically over the years (first as a teenager when I discovered the novels and short stories, then a couple of years ago inspired by Black Lives Matter, and now for his centenary), and there is much to be savoured here, that can enrich my understanding. I supplemented the reading (I also re-read Go Tell it on the Mountain, and I am not your Negro) with watching some of Baldwin’s interviews, and as always, I find his voice so very compelling. He doesn’t do soundbites or inspirational quotes – when he talks about politics it is all about narrative, the narrative of the African American chained and trafficked and exploited, and then subjected to segregation and the daily evidence of white hatred. Rewatching his ‘debate’ with Paul Weiss was rage-inducing, Weiss’s complacency in his own privilege staggering, but Baldwin’s narrative overwhelmed him. His speech and his writing have a rhythm, a beat, that comes from the church (he was a preacher in his late teens), and from blues and jazz. He’s never less than piercingly articulate, and never less than fiercely passionate, but more than that, his humanity always shines through.

Graham Robb – The Discovery of France: A Historical Geography from the Revolution to the First World War

It’s described as historical geography but it’s also what I would have called social history – it’s about the people who didn’t make it into the history books, and who were for the most part buffeted by Great Events rather than playing an active role in them. And really, as the title suggests, it’s about how little the concept of ‘France’ meant to most of those people, vast numbers of whom did not speak any language resembling French (perhaps one of the reasons why the Académie is so protective of that language now). It also provides a fascinating context for the 19th century novels I’ve been reading since my teens – Balzac, Flaubert, Zola.

Sathnam Sanghera – Empireland: How Imperialism has Shaped Modern Britain

My schooling until the 11+ year was in two newly independent West African nations. Whilst I mixed primarily with other ‘expatriates’ I could not be unaware (and my parents were profoundly aware) of the reasons we were out there, and how the legacy of empire was still playing out. My understanding may have been primitive (I was 9 when we left) but it influenced my thinking about so many things as I grew up. So it was fascinating to read Sanghera’s exploration of the ramifications of our imperial history in British culture and politics. It is clear-sighted and forward looking, and asks what we do once we have recognised what empire did to its overseas subjects and what it did to those who grew up here in its shadow.

Claire Wills – Lovers and Strangers: An Immigrant History of Postwar Britain

The story of immigrants from the wreckage of the war in Europe, from Ireland, from the Caribbean, from across the Commonwealth, at work, at home and at play. It’s a rich and varied picture – the experiences of immigrant life varied enormously as one would expect depending on why they came, where they came from and who they’d been in their previous life. Some of these stories are familiar but a great many are not, and it is good, in particular, to get beneath the generalisation of ‘Asian’ to explore the very different communities who arrived, with different expectations, and different challenges to their integration.

The music in my head (part 2): West Africa and beyond

Posted by cathannabel in Africa, Music on November 1, 2015

To add to my most recent piece about the music of Mali, here’s a great piece from That’s How the Light Gets In on West African music (with a strong emphasis on Mali, naturally!)

This is the second of three posts which round up some of the music that I’ve enjoyed in 2015 but never got round to writing about. This one discussed music from beyond these shores that I have been listening to in 2015, particularly some fine West African releases.

View original post 1,592 more words

The 24 Hour Inspire!

Posted by cathannabel in Events, Science on February 23, 2013

The 24 Hour Inspire!

24 hours of lectures in celebration of Dr Tim Richardson

Thursday 28 February-Friday 1 March

Hicks Building, Lecture Theatre 1

University of Sheffield, Hounsfield Road, Sheffield S3 7RH

Tickets on the door, minimum £1 per lecture or £5 for the full programme. Refreshments on sale throughout the event. Inspiration for Life raises funds for Weston Park Hospital Cancer Charity and local hospices (Rotherham, St Luke’s and Bluebell Wood).

For more information, please visit our website, http://www.inspirationforlife.co.uk.

Email: cath@inspirationforlife.co.uk Twitter: @inspirationfor2

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Inspiration-for-Life/

THURSDAY 28 FEBRUARY

17.00-18.00 Introduction – Catherine Annabel, Chair of Inspiration for Life

Is Science Magic? – Professor Richard Jones, Pro-Vice Chancellor, Research & Innovation and Professor Tony Ryan, OBE, Pro-Vice Chancellor, Faculty of Science

New science and technology can seem like magic – but how deeply do the connections go? New sciences like nano-technology and synthetic biology promise magical possibilities, like invisibility cloaks, shape-shifting objects that make themselves, and miniature robot surgeons to cure all our diseases. Can science, like the promise of magic, solve all our problems and realise our dreams? Or are we in danger of waiting around for magical answers to problems like climate change and sustainable energy rather than doing the hard work of solving our problems with the tools we have? This discussion between Tony Ryan and Richard Jones will explore some new science that looks like magic, but is very real, as well as finding some unexpected historical connections between the worlds of science and magic.

18.00-18.30 The End is Nigh: Impact Probabilities and Risk – Dr Simon Goodwin, Reader in Astrophysics

How often are we hit by asteroids? What risks are associated with impacts from space and what can we do about them?

18.30-19.00 Hope for the Innocent? – Professor Claire McGourlay, Innocence Project & Freelaw Manager, School of Law

A small insight into miscarriages of justice in the UK and the inspirational work that students do across the country in helping to give hope to innocent people.

19.00-19.30 Future Gas Turbine Technology -Dr Jamie McGourlay, Partnership Manager, Rolls Royce plc

Jamie McGourlay is the Rolls-Royce Partnership Manager with the Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (AMRC) of the University of Sheffield, an environment literally at the cutting edge in the development of high-value manufacturing technologies. His presentation will look at the current to future challenges involved in the design, manufacture and operation of the world’s best gas turbine technology.

19.30-20.00 Though We Fail, Our Truths Prosper: John Lilburne (1614-1657) and the slow victory of human rights

Professor Mike Braddick, Professor of History, Pro-Vice Chancellor, Faculty of Arts & Humanities John Lilburne was a radical campaigner for the rights of the ‘freeborn Englishman’ during the English civil war and revolution. He was on trial for his life three times, and in prison or exile for most of his adult life. Despite these ordeals, his central political ideas are now taken for granted, and many of his specific suggestions have become central to our constitution. They have also had a liberating influence around the world. I will give a brief account of his life and ideas, how he came to have them, and how his political tactics have provided a model for later radicals. It is a dramatic and inspiring vindication of his famous claim that despite the apparent failure and suffering he experienced, the truths for which he was campaigning would, in the end, win out: ‘though we fail, our truths prosper’.

20.00-20.30 Searching for the Higgs Boson at the Large Hadron Collider -Professor Dan Tovey, Professor of Particle Physics

On 4 July 2012 the ATLAS and CMS collaborations at the CERN Large Hadron Collider announced the discovery of a new particle believed to be the long sought-after Higgs boson. This talk will describe the background to the discovery and how it was made, and explain its significance for fundamental physics and our understanding of the universe at the smallest and largest scales.

20.30-21.30 Beyond Dentistry: On The Mouth, Kissing and Love – Dr Karen Harvey, Senior Lecturer in Cultural History/Academic in Residence at Bank Street Arts, and Dr Barry Gibson, Senior Lecturer in Medical Sociology, School of Clinical Dentistry

The meanings given to the mouth have changed over time. Our modern dental rituals might be part of a longer ‘de-spiritualisation’ of the body. In the end, though, let’s not forget kissing and love …

21.30-22.00 This is not a Lecture. Stories of Wellbeing – Professor Brendan Stone, Professor of Social Engagement and the Humanities

This talk will tell stories of personal journeys, journeys which have been deeply informed by the storied lives of others. The journey of the self may be to seek meaning, affirmation, peace, or connection, but is often diverted or abandoned when illness or trouble strike. How can we retrace our steps and take up our route again at such moments of loss?

22.00-22.30 From Bones to Bridges – Gaining Strength from Structure – Dr Matthew Gilbert, Reader in Civil & Structural Engineering

Why might the internal structure of bones be of interest to the designers of buildings and bridges? How does the layout of elements in a structure affect its strength? And how can we identify layouts with the ‘best’ properties?

22.30-23.00 The Big Bang Theory of Lifelong Learning (in which Sheldon teaches Penny Physics) – Dr Willy Kitchen, Director of Learning and Teaching, Institute for Lifelong Learning

In this brief talk, I will offer up some of the essential ingredients necessary to inspire lifelong learning, drawing upon my own experiences of working with a wide range of adults returning to learning after a significant break from education. As a jumping off point for my discussions, I will be offering Sheldon some feedback on the approach he takes to teaching Penny Physics.

23.00-23.30 The EU’s Fight against Cancer – Professor Tammy Hervey, Jean Monnet Professor of European Union Law, School of Law

The European Union is a trade organisation, concerned with creating markets and economic development. For a long time, it had no formal powers to develop health policies of any sort, and even now, its powers are limited. And yet the EU has contributed to the fight against cancer in numerous ways, including using policies, resources, and laws. This lecture will explain the history of the EU’s fight against cancer, and outline what more could be done in the future.

23.30-00.30 Taking up the Ghost – Professor Vanessa Toulmin, Director of National Fairground Archive, and Head of Cultural Engagement

From Robertsons’s fantasamagoria in the 1790s to the modern day theatrical horror promenade show, the staging of haunted attractions as popular entertainment has been part of our history for many years. This paper seeks to look at three historical entertainment concepts which incorporate or use as their basis the uncanny, the supernatural and sensory deprivation, incorporating technological practices from the magic lantern, photographer and the cinematograph to demonstrate how the haunted illusion works in popular entertainment.

FRIDAY 1 MARCH

00.30-01.00 The Blues of Physics – Dr Ed Daw, Senior Lecturer in Particle Physics & Astrophysics

Physics can be a great and wonderful joy. And it can also give you the Blues. Fortunately I was given the Blues independently of being given Physics, so when the latter drives me bananas, the former can step in and keep me slightly insane. Please come to my ‘lecture’ and listen to my attempts to keep myself slightly, and joyfully, off-kilter.

01.00-01.30 Deep Sky Astronomy and Astrophysics – Professor Paul Crowther, Professor of Astrophysics

I will present astronomical images of star clusters, nebulae, galaxies obtained with large ground-based telescopes (ESOs Very Large Telescope) and space-telescopes (Hubble, Spitzer, Herschel) together with an explanation of the astrophysics behind these inspirational and beautiful images.

01.30-02.00 Light of Life – Dr Ashley Cadby, Lecturer in Soft Matter Physics

Humans and nature both use light for a variety of reasons. In this talk I will take some specific examples from nature and show how, given several hundred million years, evolution has perfected the control of light to perform some remarkable feats of engineering.

02.00-02.30 How to Make the Perfect Cuppa – Dr Matthew Mears, Lecturer, Department of Physics & Astronomy

Not all physics research is serious and swamped in mathematics! Tim firmly believed that you should have fun and explore the field away from the expected route, a philosophy I have enjoyed following. In this talk I will discuss what happens when a) a physicist starts crossing subject boundaries in strange directions, and b) he gets fed up with his brew going cold.

02.30-03.30 A Beginners Guide to Nano – Professor Mark Geoghegan, Professor of Soft Matter Physics

This presentation will cover the origins and applications of nanotechnology. A working definition for nanotechnology will be presented with examples from various areas of technology where nano might be used. In particular, I shall discuss how nanotechnology might find an important role in solving the great issues facing us in the 21st century. You will be encouraged to consider what these might be. Fears about unleashing this technology on mankind will be discussed, and we shall consider, by comparing the physics of the macroscale with physics of the nanoscale, why impending apocalypse is not going to happen.

03.30-04.00 Pet calves: The science of drumming – Professor Nigel Clarke, Professor of Condensed Matter Theory, Head of Physics & Astronomy

Drums are probably the oldest of musical instruments, and their basic form has changed little over the centuries. In the 1950s a major revolution took place with the introduction of the synthetic drumhead, which very quickly gained universal acceptance, replacing calfskin and other animal skins, as the material of choice. This was driven not by musical benefits but by pragmatism. We will look at the science behind drums and drum-skins, including the way in which drums vibrate, the pitchless nature of many drums, the implications for tuning and the relative merits of synthetic and natural drum-skins.

04.00-05.00 The Origin of Mass – Dr Stathes Paganis, Reader in Particle Physics

What are we made of? What is mass? Einstein tells us that mass is energy: E=mc^2. Basic physics tells us that the mass of our body comes from the chemical elements that make us, water for example. Water is made of hydrogen and oxygen and these are made of protons, neutrons and electrons spinning around them. How deep do we have to look for the answer? The talk presents a travel to the origins of matter and explains how experiments show that mass is not due to the Higgs boson but due to quantum mechanical energy stored in protons and neutrons one millionth of a second after the Big Bang.

05.00-05.30 Red Wine and Tea: Short tales about Astringency – Dr Patrick Fairclough, Reader in Polymer Chemistry

I will wander, often aimlessly, through ideas around how your mouth senses changes not in taste but in viscosity (thickness). How this leads to ideas behind the science of astringency, and how the tannin in tea and red wine induces these changes. Astringency is poorly understood with conflicting views from taste experts, physicists, biologists, industrial scientists and “marketeers”. This will clearly require me to drink red wine during a lecture, something that I often felt the need to do.

05.30-06.30 Elena Under Her Skin – Professor Elena Rodriguez-Falcon, Professor of Enterprise & Engineering Education, Department of Mechanical Engineering

What happens when people see past the front cover of your life? Are you still able to have a happy, successful and rewarding work/life experience? Does one achieve despite or because of our mixture of experiences and attributes? Elena will use her life as a point of conversation with the audience and reflect on various aspects of diversity in the workplace such as religion, sexuality, nationality and gender.

06.30-07.00 Inspiration, Risk and the Politics of Fear – Professor Matthew Flinders, Professor of Parliamentary Government & Governance, Department of Politics

A reflection on the nature of life and politics in the twenty-first century. This will include a discussion of hyper-democracy and the politics of fear in order to carve out a new approach to understanding the limits and possibilities of democratic politics.

07.00-07.30 Gas Sensing Biscuits and Other Research by ‘Team Tim’ – Dr Alan Dunbar, Lecturer in Energy, Department of Chemical & Biological Engineering

Some of the work published by Dr Tim Richardson’s research group ‘Team Tim’ will be presented. This involved developing gas sensors which change colour upon exposure to volatile organic gases. This talk will gently introduce the porphyrin molecules used in these gas sensors and explain why they are sometimes described as being like biscuits.

07.30-08.00 Soaps, Bubbles and Cells – Dr Andrew Parnell, Research Associate, Department of Physics & Astronomy

The talk and demonstrations will highlight the amazing properties of soap molecules and how very similar structures make up the walls of our cells and ultimately help to construct the complex compartments essential for biological life.

08.00-08.30 Health Informatics: Opportunities and Challenges in the 21st Century – Professor Peter Bath, Professor of Health Informatics, Information School

Health Informatics concerns the use of digital information and digital technologies in health and medical care to improve health and well-being among patients and the public. This lecture will examine some of the exciting opportunities and challenges in this fast-moving field. It will draw on recent research undertaken to examine the use of NHS Direct by older people and will discuss the implications of this for the new 111 service.

08.30-09.00 Infinity! – Dr Paul Mitchener, Lecturer in Mathematics, School of Mathematics & Statistics

The plan is to talk about what infinity means mathematically. This will include a precise definition, which leads to the surprising idea that there is more than one type of infinity.

09.00-09.30 We are all living in a Bose-Einstein Condensate… made of Higgs Bosons – Professor Sir Keith Burnett, Vice-Chancellor

What is this Higgs Boson? What does it tell us about the nature of the Universe? Using familiar examples, I will tell you what Bosons are, how they condense and explain the origin of mass in the Universe.

09.30-10.00 Four Candles? Or was it Fork Handles? – Marie Kinsey, Senior University Teacher, Director of Teaching and Curriculum Development, Department of Journalism

Communication is a two way process. There’s endless scope for accidental misunderstandings, miscommunication and just getting things plain wrong. What can you do to help make sure your message gets across loud and clear?

10.00-10.30 A Brief History of the Universe – Professor Carsten van de Bruck, School of Mathematics & Statistics

I will review our current understanding of the history of the universe. But more importantly I will let you know what we don’t know. Many puzzles need to be solved before we have a full understanding of how we got here.

10.30-11.00 Science, Art and Human Rights – Professor Aurora Plomer, Professor of Law and Bioethics, School of Law

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) states that “Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.” I will talk about what the drafters meant then and what the right means now.

11.00-12.00 Seeing the World – a talk for primary school children – Professor David Mowbray, Department of Physics & Astronomy

The talk will look at some of the properties of light. It will cover how we see things in the world around us and the uses of light. Colours will also be investigated. There are a number of demonstrations which the children help with.

12.00-12.30 Birds, Poetry and Music – Professor Rachel Falconer, Professor of English Literature, University of Lausanne

This talk provides an introduction to contemporary nature writing, with a focus on poetry written about birds. It touches on the long history of poets’ fascination with birds, explores some of the links of this tradition with music about birds, and presents a detailed look at three short poems by contemporary British poets.

12.30-13.00 The Human Body: an Anatomist’s View – Professor Alistair Warren, Professor of Biomedical Science, Director of Learning & Teaching, Faculty of Science

Art, science, medicine, literature and ethics. All of these subjects and many others have their own perspectives on Anatomy. These have changed dramatically over the years; I aim to give a personal view of what it means to be an Anatomist in the 21st century.

13.00-13.30 Is Anybody Out There? Intelligent Life in the Galaxy – Dr Susan Cartwright, Senior Lecturer in Particle Physics & Astrophysics

Are there other intelligent technological species out there, or are humans rare (or even unique)? I will examine a number of arguments that technological civilisations are rare.

13.30-14.00 Prejudice and Self-Knowledge – Professor Jenny Saul, Professor of Philosophy, Head of Philosophy Department

Psychologists have shown that the overwhelming majority of people harbour unconscious race, sex and other biases. In this talk I explore how this threatens our knowledge both of ourselves and of many other things.

14.00-14.30 Sources – Dr Chamu Kuppuswamy, Lecturer in Law, Café Scientifique Organiser

In this lecture I want to discuss the tension between traditional and modern sources of law. This is a big point of debate in international law in the context of devising new regimes for the protection of our intellectual resource and heritage. In the 21st century where intellectual property is central to economic and social growth and prosperity, this arena of contestation has an impact on our everyday experience of music, books, dance, medicine, sculpture, health, etc. Culture and identity are being shaped through these battles for supremacy. In an effort to look inwardly at the notion of sources, and why it is important to us, I venture into sources and truth, probing the subjective and objective how this is viewed in Indian philosophy. Chamu is an international lawyer with special interests in intellectual property, a keen student of Vedantic Hinduism and enthusiast for all forms of enquiry including the scientific.

14.30-15.00 Living Matter – Professor Ramin Golestanian, Professor of Theoretical Condensed Matter Physics, Oxford University

The large and important and very much discussed question is: How can the events in space and time which take place within the spatial boundary of a living organism be accounted for by physics and chemistry?’. This sentence, which was written by Erwin Schroedinger on the 1st page of chapter 1 of his visionary 1944 book, What is Life?, describes a notion that is still as illusive today as it was back then. I will highlight some of the marvellous and complex physical properties of living systems, and try to put them in context using ideas from physics and chemistry.

15.00-15.30 Darwin and Sexual Selection – Professor Tim Birkhead, Professor of Zoology, Department of Animal & Plant Sciences

The male Argentine Lake Duck has the most extraordinary genitalia of any bird. The Harlequin Duck by comparison is extremely modestly endowed. Why should such differences exist? After all a phallus is a phallus, and on on the face of it, all serve the same purpose, so why such extraordinary variation? This type of question has intrigued and perplexed biologists and non-biologists alike for centuries. The answer was a long time coming. Not until the revolution in evolutionary ideas, and a century after Darwin, was the truth revealed.

15.30-16.00 Studying the Muse: The Psychology of Creative Inspiration – Dr Kamal Birdi, Senior Lecturer in Occupational Psychology, Institute of Work Psychology

Have you ever wondered where great ideas come from? In this lecture, we’ll look at different psychological perspectives on answering this question, from experiments on romantic impulses to creating machines that make up stories!

16.00-17.00 Catalytic clothing – Professor Tony Ryan OBE & Professor Helen Storey MBE

The speakers will be wearing the world’s first air-purifying jeans, embedded with the technology that we hope will be applied in the laundry process so you too can purify our air. Catalytic Clothing explores the potential for clothing and textiles to purify the air we breathe. Artist and designer Helen Storey (London College of Fashion) and chemist Tony Ryan (University of Sheffield) have been working together to explore how nanotechnology can eliminate harmful pollutants that cause health problems and contribute to climate change. We will explore how nanotechnology can be used to solve an everyday problem. It has been seen by millions of people, and there is a great demand. Of course there are still technical problems to solve, but the the biggest problem in getting it to market is getting past the marketeers. This is a truly altruistic product – but to make it happen might need a new business model.

Finale