Archive for December, 2025

Love is in the noticing – thoughts on 2025

Posted by cathannabel in Personal on December 31, 2025

This is a purely personal take on 2025. I cannot bear to bring to mind, let alone attempt to write about, what this year has been in terms of world events and politics at home. This is cowardly, I know, but there are better minds than mine grappling with the state of things, and all I could do would be to repeat uselessly how absolutely bloody awful everything is, and how hard it is to see any glimpses of hope, as the handcart in which we are going to hell appears to gather speed. So, I will talk about my little world instead.

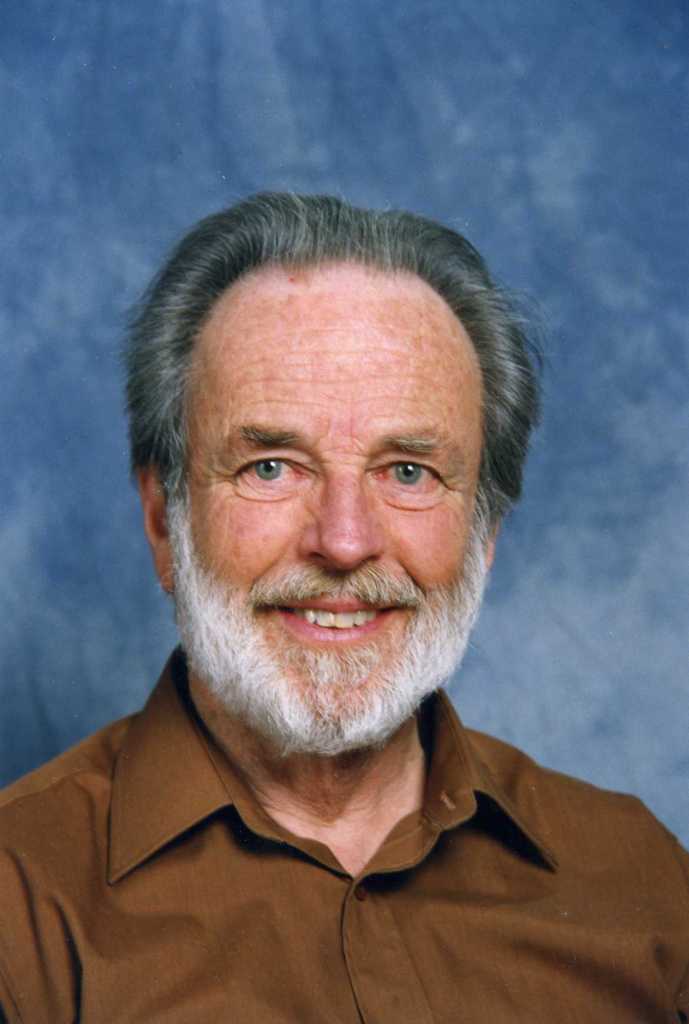

2025 – the year when my father’s hold on life finally slipped, after 97 years and the erosion of his mind and memory by dementia. I reflected on his life here. Writing about him, on this site and on the Guardian’s Other Lives obituary section, was my way of honouring who he was, before.

And it was a year when we celebrated love, companionship and family as my daughter married her partner of ten years – a purely joyful day, as the sincerity and seriousness of their commitment was expressed joyfully, as everyone there shared in their joy. Of course we were conscious of the people who should have been there but, as Tracy Thorn puts it in her song ‘Joy’, ‘because of the dark, we see the beauty in the spark’. It was a deeper thing than just happiness or contentment, and that’s because we were aware, we could not be unaware, of mortality and of the fragility of life but at the same time, daring to rejoice in the couple’s commitment to their shared future.

A year when I decided to take my health seriously, something I just couldn’t put my mind to for a while after M died. It had to be sustainable change, anything else is simply demoralising. I changed my diet (I didn’t ‘go on a diet’, I’ve been there, done that, and it is always miserable and always short-lived), and I stopped drinking alone (I’d been kidding myself it was making evenings on my own feel better, but it really wasn’t, and in the early hours of the morning, it felt a lot worse). And having discovered that Pilates is a form of physical exercise that I actually enjoy (who knew there was such a thing?) I added two live on-line classes to my weekly studio class, and found myself really making progress. Now, I didn’t do any of this with the intention of losing weight, which is a good thing, because I have lost not one ounce or one inch. But because I had other goals than that, I can be philosophical about the weight thing, rather than seeing it as a failure. I’m healthier, physically and mentally, and that’s enough. (By the way, if you feel moved after reading this to send me links to miraculous weight-loss techniques, please note that they will be deleted unread and you will be blocked. Cheers!)

Late last year I took on the role of Chair of the Under the Stars Board of Trustees. One of my best decisions ever was to join them as a trustee in 2023, and to be part of the incredible work they do. I feel privileged to be able to support the staff and the CEO in particular, and to see our participants finding joy in performing on the Crucible stage, at the Tramlines festival, and a variety of other venues. Stephen Unwin’s book Beautiful Lives, which traces the history of attitudes to people with learning disabilities and looks at how we can do better, was my non-fiction read of the year (see my books blog). It’s heartbreaking and horrifying – not just the murder of ‘useless mouths’ during the Nazi era but the denial of agency and dignity for so long to so many. But it’s also hopeful, and personal, and it moved me a great deal. This year I was cheering on Ellie Goldstein, who has Down’s Syndrome, as a competitor on Strictly Come Dancing. She gave the lie to any idea that ‘learning disability’ means inability to learn, as she grasped complex sequences of tricky dance moves that I would never be able to hold on to – whenever I was at a disco in my younger years I used to head for the loo or the bar when some kind of Macarena/Timewarpy thing got going (I can just about do the Conga). And this year Nnena Kalu, an artist with learning disabilities, was awarded the Turner Prize. If we stop putting all those with LD in a box together, and start listening to them as individuals, finding out what they can do, what they love doing, what hurts them and what gives them confidence, they will achieve more, and they will have a shot at finding joy. I’ve seen it, and I’ve found joy in it myself.

One of my big projects for 2025 has not yet come to fruition – finding a publisher for The Thesis. But I have a better sense of how it needs to be revised and reshaped to make that more likely and, too, a better sense of how much I can realistically do/am willing to do. It’s easier to do that kind of work when you’re within the context of a University, with full access to physical and electronic resources and to people who know stuff. But it’s not just that – I’m older than when I did the PhD, and I’m on my own now, and I don’t have the energy I had ten years ago. So I’m going to update the thesis, taking account of material published since I submitted it, and adapt it to address a wider readership rather than an external examiner. I want it to intrigue and interest readers rather than to prove myself as a scholar. I think that’s feasible, and so I’m not giving up on my dream of seeing the piece of work that absorbed and fascinated me for so long as a published book.

It’s now over four years since M died. The process continues. I’ve adapted lots of my domestic routines of course, and changed a lot of things around the house to make it fit me better. I’ve taken big decisions where I had to (the knee replacement surgery, getting rid of the car), and squillions of smaller decisions as I re-evaluate what I do and how I do it. My big decision for 2026 (so far) is that I will be going on an ‘escorted tour’ taking in Helsinki, Tallinn and Riga, three cities I have never visited and know only a little about. It may turn out that it’s not the sort of holiday that works for me, but if it is, it opens up so many possible ways of travelling and seeing new places. It’s a bit scary – I’m an introvert, and am fairly crap at small talk, and the trip will inevitably involve talking to strangers – but going on an organised tour makes some things a lot easier to contemplate as a solo traveller (see my blog about my previous city break with my son for all the reasons why it might make me rather anxious).

I suppose at some point ‘widow’ will cease to be a defining word for me, but at this stage in the process, it still feels deeply significant. I am still conscious all the time of his absence and it still feels strange – only recently I’ve had the sensation sometimes when I half-wake in the night that I’m not on my own and then the realisation that of course I am. I don’t mean I sense his presence, just that, whilst I’m fully awake I am used to the strangeness of solitude, but in those drowsy moments it puzzles me. I talk about him a lot, to family and friends who knew him, and to people who never knew him, because I can’t talk about my life without talking about him. I switch between ‘I’ and ‘we’ constantly and probably not consistently, because my adult life comprises a ‘before’ and an ‘after’. It’s not that ‘I’ was subsumed in ‘we’, just that our lives were so tangled up together ‘before’.

The title for this post is a quote from the Pixar film Soul, which I used in my speech at my daughter’s wedding last August:

“Life isn’t about one big moment. It’s the little things: walking with someone you love, sharing a laugh, watching the light hit their face just right. Love is in the noticing. The ordinary days that turn out to be everything. And maybe the whole point isn’t to chase the grand purpose, but to love deeply, and really live, right where you are.”

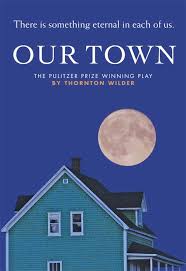

I don’t know whether the writers of Soul were consciously echoing Thornton Wilder’s play Our Town, but it’s not too much of a stretch to think that they were, given how popular the play is in the US. I recently read Ann Patchett’s stunning novel, Tom Lake, in which the play is the thread that runs through the narrative, and was so struck by it that I sought out and watched on YouTube the televised stage version with Paul Newman. And this, in the final act, jumped out at me:

EMILY: ‘Live people don’t understand, do they?’

MRS GIBBS: No dear – not every much.

EMILY: They’re sort of shut up in little boxes, aren’t they? … I didn’t realise. So all that was going on and we never noticed. … Oh, earth, you’re too wonderful for anybody to realise you. Do any human beings ever realise life while they live it? – every, every minute?

STAGE MANAGER: No. [Pause] The saints and poets, maybe – they do some.

Maybe that’s right, we can’t realise or notice every minute, we’re too busy living them, but we can try – to notice and to treasure. There are two strands of thought here for me. One is that the ordinary days ‘turn out to be everything’, a theme that I explored in my eulogy for M, focusing on the day before he died, about which I would remember hardly anything except that it was the last ordinary day, and thus extraordinary. The other is that joy is something we hope for rather than being able to predict or plan for, but that finding it depends on us noticing, noticing the people who we love and who love us, the beauty in music, in words, in the landscape or skyscape. And it depends on us realising that there’s a kind of defiance in joy, that it faces down the dark, the loss and grief, not denying them but just saying ‘there is also this, and this is marvellous and wonderful’, throwing the joy in those marvellous ordinary days in the face of whatever the year might bring.

I look back at 2025 with gratitude to all the people who made it good. Wonderful family and friends, sharing each other’s joys and sorrows. The care home staff who looked after Dad, treated him always with affection and respect, and held his hand as he slipped away. The Under the Stars team and our participants. The musicians who stirred my soul, my mind and my feet. The writers whose words allowed me to cross continents and centuries and to see into other people’s hearts and minds.

So as we move from one year into another, let’s ‘gather up our fears/And face down all the coming years’. Let’s hang on to our hats, hang on to our hope, let’s keep on keeping on. See you on the other side…

Tracy Thorn, ‘Joy’, from Tinsel & Lights, 2012

When someone very dear

Calls you with the words “everything’s all clear “

That’s what you want to hear

But you know it might be different in the New Year

That’s why, that’s why we hang the lights so high

Joy, Joy, Joy, Joy,

You loved it as a kid, and now you need it more than you ever did

It’s because of the dark; we see the beauty in the spark

That’s why, that’s why the carols make you cry

Joy, Joy, Joy, Joy Joy, Joy, Joy, Joy

Tinsel on the tree, yes I see

The holly on the door, like before

The candles in the gloom, light the room

the Sally Army band, yes I understand

So light the winds of fire,

and watch as the flames grow higher

we’ll gather up our fears

And face down all the coming years

All that they destroy

And in their face we throw our

Joy, Joy, Joy, Joy

It’s why, we hang the lights so high

And gaze at the glow of silver birches in the snow

Because of the dark, we see the beauty in the spark

We must be alright, if we could make up Christmas night.

Music Nights 2025

Posted by cathannabel in Music on December 23, 2025

My year in live music – opera, jazz, chamber music, indie, folk, all sorts – and forays into the CD/vinyl collections. Four years of listening to music without M, and I still feel it’s somehow a shared thing. I don’t spookily ‘sense his presence’ but what I listen to and how I listen to it is still – and probably always -connected to the way we listened together. That includes embracing new stuff, resisting the tendency to get stuck in a genre or decade, and listening as an active process, not as an ignorable background to whatever else one is doing. This year’s music has been full of moments when I wanted to turn to him and say ‘hey, listen to this bit!’, or ‘doesn’t that remind you of x?’ or just ‘wow!’.

I had a feeling I’d been to more gigs this year than last, and so it proved when I totted them up – 41, plus Tramlines, as against 25 plus Tramlines the previous year. More different venues as well, 17 this year as against 14 last. I decided to list them chronologically rather than grouping them by genre or such like.

The only problem with going to so many gigs is that it’s hard to come up with something to say about each (I find it harder in any case to write about music, other than to splurge a lot of superlatives onto the page, than about books or film or TV). So I’ve commented where there was something particularly notable about the gig or the context, and have hinted at what some of my top gigs were this year, but both the musical genres and the experience of hearing them are so diverse that it makes any kind of Top 3 or Top 10 a bit arbitrary, so I haven’t done that (I make the rules).

Some of these concerts – probably most of the Music in the Round ones – I went to on my own. Somehow sitting in the Crucible Playhouse or in the pews at the Upper Chapel on one’s own seems much less odd than being solo at Crookes Social Club when it’s got cabaret seating, or even at a standing gig. I was and am determined not to miss out on live music just because I can’t find someone to go with, but there is, I acknowledge, a whole other dimension when one is sharing the experience. I shared the opera with Ruth; the Unthanks in Elmet with Ruth and Aidan; The Midnight Bell with Claire; Sheffield Jazz gigs with Adi, Jennie and Michael; Tramlines with Arthur, Sam, Jane and Richard; Bach solo violin, Schubert & Janacek, and Nigel Kennedy with Arthur and Gabi; various Under the Stars bands with colleagues and participants; Songhoy Blues with Jane, Richard, Jennie & Michael; Gong with Aidan; and Shostakovich and Messiaen with Liz.

January:

Tommy Smith & Gwilym Simcock, Sheffield Jazz (Crucible Playhouse). Smith is a top-notch sax player, and here he was performing with a top-notch pianist, for what the programme described as ‘an acoustic night of intensely musical duets and dazzling improvisation’, bringing together two generations of jazz mastery for ‘an evening of intimate musical brilliance’. Absolutely.

Kurt Weill – Love Life, Opera North (Leeds Grand Theatre) – an opera we didn’t know at all, and which is only rarely performed, for some reason. It opened in 1948, and has been revived a couple of times since, most notably in this production. It’s a product of the study Weill made of American popular song after he arrived in the US as an exile from Nazi Germany, with vaudeville numbers that provide a commentary on the narrative. The story itself is of a married couple who we first meet in 1791, and whose lives we follow through to 1948 – they don’t age but the world changes around them and thus changes them and the nature of their relationship. We loved the concept, the performances, the staging, and above all the songs.

February:

Richard Wagner – The Flying Dutchman, Opera North (Leeds Grand Theatre) – a rare occasion (I think the only one, actually) when we weren’t persuaded by the setting or the concept behind the production. The idea was to link the myth of the Flying Dutchman, constantly moving on, unable to find a home anywhere, with the story of the refugee – certainly an interesting concept, but the narrative of the opera couldn’t really be shoehorned into this without many jarring moments, and some loss of comprehensibility. The music, of course, was magnificent.

Benjamin Nabarro – Bach for Solo Violin: Sonata No. 1 in G minor/Partita No. 1 in B minor, Music in the Round (Upper Chapel). Superb performances from Ben, the lead violinist in Ensemble 360.

Valentine’s Voices – Daisy Daisy, Julian Jones, Sparkle Sistaz, Rye Sisters, PLUC, December Flowers, Banjo Jen, Clubland Detectives (Crookes Social Club – fundraiser for Under the Stars). Sparkle Sistaz and Clubland Detectives are two of the bands formed in the music workshops that Under the Stars run for adults with learning disabilities and/or autism. This event was a brilliant collaboration between our own artists and various local bands and solo performers.

March:

Gareth Lockrane Quintet, Sheffield Jazz (Crookes Social Club). Superb fluting from Lockrane who, according to the publicity material, ‘plays all the flutes’ – he certainly played quite a few over the course of the evening. The other quintet members were Nadim Teimoori on tenor sax, Nick Costley-White on guitar, Oli Hayhurst on bass, and Gene Calderazzo on drums.

Power: Shostakovich (Ensemble 360): Piano Trio No.2 Op.67/Piano Quintet Op.57 (Firth Hall). This was preceded by a fascinating talk about Shostakovich’s precarious position in Stalinist Russia. The music was just stunning.

Hejira, Sheffield Jazz (Crookes Social Club). Hejira perform Joni Mitchell songs – it could just be a top-notch tribute band but it feels like more, they are interpreting the songs rather than trying to replicate Mitchell’s performances. Brilliant.

Classical Sheffield Weekend:

- Ensemble 360 – Beethoven for Flute: Flute Sonata in B flat/Trio for piano, flute and bassoon (Upper Chapel)

- Sounds of Heaven – Sheffield Chamber Choir, Steel City Choristers, Sterndale Singers and Sheffield Chorale, each getting their own spots to perform, with music by Will Todd, Sarah MacDonald, Eriks Esenvalds, Palestrina, Grieg, Parry, Part, Purcell, Rheinberger, Macdonald, arrangements by Vaughan Williams, Donald Cashmore, and Shena Fraser, and then all coming together for a spine-tingling Tavener’s ‘God is with us’. (St Marie’s Cathedral)

- Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus – Fauré – Requiem, Finzi – Lo, the Full, Final Sacrifice, Stephen Johnson – The Miracle Tree/To Wed again/This Going Hence, Thomas Stearn – for music like the sea (Curlew at Redmires) (St Marie’s Cathedral)

April:

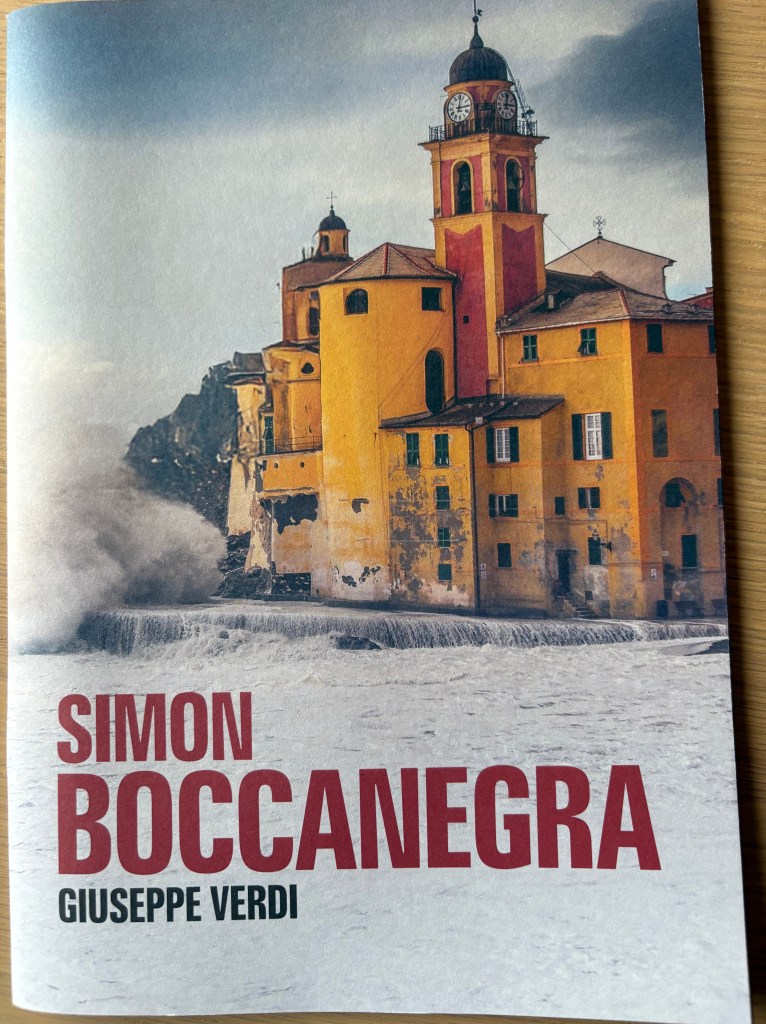

Giuseppe Verdi – Simon Boccanegra, Opera North (St George’s Hall, Bradford). Brilliantly stripped-down staging, and the music was wonderful.

May:

Misha Mullov-Abbado, Sheffield Jazz (Crookes Social Club). Lovely stuff – the music was from their new album Effra, very varied and beautifully played by Misha Mullov-Abbado on bass with James Davison: trumpet & flugelhorn, Tom Smith: alto sax, Sam Rapley: tenor sax, Liam Dunachie: piano and Scott Chapman: drums.

Chamber Music Festival, Music in the Round. This year’s festival was curated by Ensemble 360 to celebrate their 20th birthday, and I wish I could have gone to more than the five gigs I managed. (all in Crucible Playhouse unless stated otherwise):

- Festival Launch: Huw Watkins – Broken Consort, Aileen Sweeney – Equinox, Schubert – Octet. A great start to the Festival – Aileen Sweeney’s premiere of Equinox was lovely and I want to hear more of her work, and the Schubert Octet is a piece I’ve heard a couple of times from Ensemble 360 and is an absolute joy every time.

- Intimate Letters: Schubert – Quintet in C Major, Janacek – String Quartet no. 2. The Janacek featured an actor reading extracts from the composer’s ‘intimate letters’ to a woman with whom he was obsessed for many years – it gave a whole new dimension to the music, and sometimes a troubling one.

- The Nostalgic Utopian Future Distance: Kaija Saariaho – Petals, Boulez – Dialogue de l’ombre double, Luigi Nono – La lontanaza nostalgica utopica futura (Firth Hall). Ensemble 360 musicians duetting with electronic sounds. Never easy but always fascinating and compelling.

- Sinfonietta: Knussen – Cantata, Ravel – Piano Trio in A Minor, VW – Piano Quintet in C Minor, Britten – Sinfonietta

- Finale: Mozart – Flute Qtet in D, Beethoven – Quintet for Piano & Wind, Elgar – Piano Quintet

Peggy Seeger – First Farewell Tour (Cubley Hall). She’s 90 so took a while to get on and off the stage (assisted by her sons), and the voice is more fragile than it once was, but she’s still got it. She sang ‘The First Time…’ (of course) and told the story of how Ewan MacColl had written it for her (‘at least’, she added wryly, ‘that’s what he told me’).

All the People Festival of Debate. Sparkle Sistaz/Clubland Detectives – (Leadmill). Two Under the Stars groups performed at this event which was all about inclusion and hearing the voices that are so often ignored.

June:

Songhoy Blues (Sidney & Matilda). I’ve loved these guys ever since we saw them at Tramlines ten years or so ago. This was a very electric – and totally exhilarating – rendition of their latest album, Héritage, which uses a lot more traditional instrumentation. Support was from the very engaging Nfamady Kouyate on balafon.

Dungworth Singers (Old Bandroom, Dungworth). Really interesting repertoire, everything from ‘Wayfaring Stranger’ to ‘A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square’ (my two favourites I think) and in between, lots of songs that I’d never heard or heard of, many from Yorkshire, but also from the the Sacred Harp tradition of choral sacred music in the US.

July:

Crosspool Festival: Dungworth Singers (Tapton Hill Congregational Church), Sheffield Folk Chorale (Benty Lane Methodist Church)

Sparkle Sistaz – Sistarz (Crucible Playhouse). A brief, tantalising preview of a musical they’re working on at present, which we hope to see in full next year.

Tramlines (Hillsborough Park): We saw/heard: Natasha Bedingfield, Cliffords, Cloud Canyons, Franz Ferdinand, John Grant, I Monster, Mackenzie, Oracle Sisters, Pulp, Pia Rose, The Second World War, Sherlocks, Heather Small, Spiritualised, Stars Band. Truth be told, being of short stature I did not literally see all of the bands listed above – where they performed on the Main Stage I did at least see the screens either side of the stage – but I heard them, and occasionally managed to manoeuvre myself into a gap that allowed me to glimpse the band for a while. Pulp were the highlight, no question, playing all the tracks you’d expect, and a lot of their fab new album. But I also rated John Grant, I Monster, and Cliffords very highly, and Heather Small’s set was just (as someone behind me in the audience said), made of sunshine. I increasingly have to pace myself very carefully to ensure that I haven’t exhausted my capacity for standing before the bands I most passionately want to see. So I’d been looking forward to Spiritualised, but missed some of their set in order to have a sit down before Pulp. Each year I go I ask myself, is this the last time, but it’s still worth it, even if I don’t clock up quite as many different bands as I used to. I’ve already bought the tickets for next time in any case…

September:

Matthew Bourne – The Midnight Bell (Lyceum Theatre). My first time with Matthew Bourne’s modern ballet, and it will not be my last. The music here is not taken from the ballet repertoire – the soundtrack, by Terry Davies, is modern, quite minimalist, interspersed with songs from the ‘30s (the setting for the piece) to which the performers mime (very Pennies from Heaven). Davies’ music is in contrast to the archive songs, conveying the inner life of the characters, as against the romantic lyrics of the songs.

October:

George Frideric Handel – Susanna, Opera North (Leeds Grand Theatre). Only my second Handel opera (I saw Giulio Cesare with M back before the pandemic). The production is excellent, very powerful, and the singers weave around and are woven around by dancers from the Phoenix Dance Theatre, whose modern dance moves provide telling contrast to the mellifluously formal Handel score.

James Allsopp Quartet, Sheffield Jazz (Crookes Social Club) – tribute to Stan Getz, ranging across his oeuvre, a lovely, warm sound and some gorgeous tunes.

The Pocket Ellington, Sheffield Jazz (Crucible Theatre). The first half was Alex Webb’s arrangement of Ellington big band compositions for four horns and a rhythm section (Alan Barnes baritone & alto sax, clarinet; Robert Fowler tenor sax, Simon Finch trumpet, David Lalljee trombone, Alex Webb piano/MD, Dave Green bass, and Alfonso Vitale drums.) Absolutely fab. See here for Richard Williams’ review of the project and of a performance, with a slightly different line-up, at Soho’s Pizza Express.

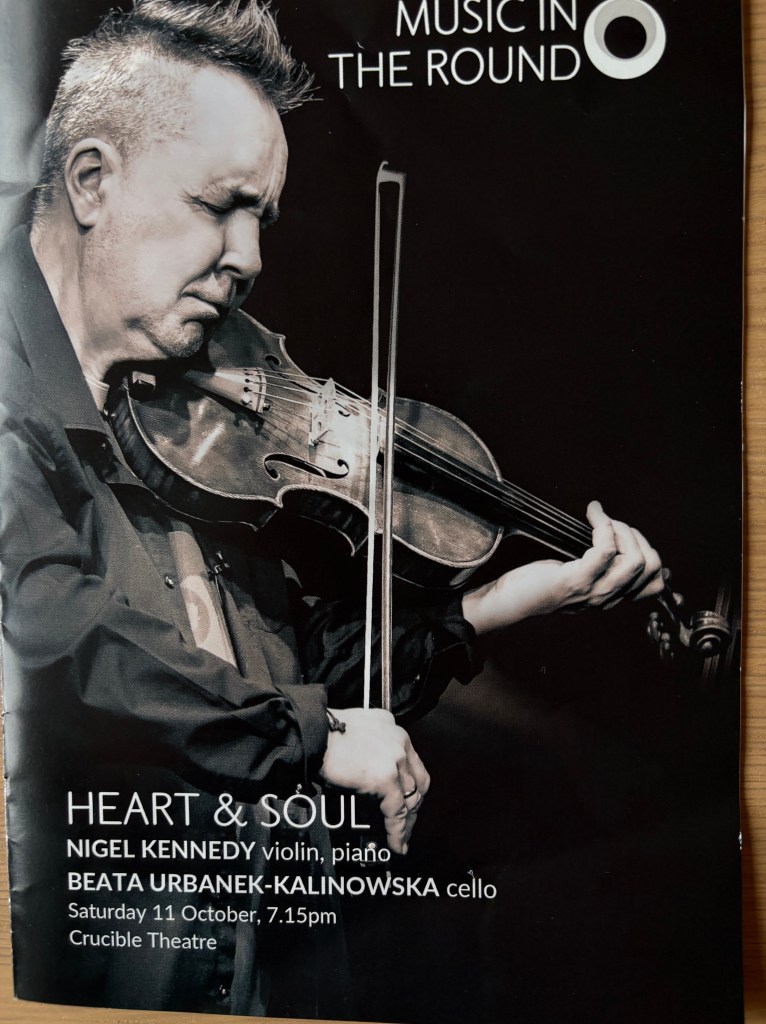

Nigel Kennedy: Heart & Soul, with Beata Urbanek-Kalinowksa (cello) – Kennedy, Komeda, Yellow Magic Orchestra Sakamoto, Bach (Crucible Theatre). Nigel is as always irrepressible and impossible to tie down, even to a set list. He borrowed a programme from someone on the front row and said ‘Oh no, it’ll be nothing like that’. In fact it was quite a bit like that, but some of the tracks on the programme never materialised, and others took their place, and there was another violinist on a couple of tracks whose name I never quite caught, a young woman who is clearly massively talented and who I’m sure we will hear of again.

Josephine Davies’ Satori, Sheffield Jazz (Crookes Social Club). Davies on sax, and Alcyona Mick on piano. The material in the first half was from her latest album, Weatherwards, inspired by the landscapes of the Shetlands where she was born, and the sound is quite different from her earlier material which was, I suppose, more immediately accessible. But the new material is definitely worth another listen.

Giacomo Puccini – La Bohème, Opera North (Leeds Grand Theatre). This is the same production that I’d seen twice before but with different casts each time. I felt Rodolfo had been a tad under-powered the second time I’d seen it, but no such problems here, and I found myself more moved by the ending than I’ve ever been before. Of course, that may be because since I last saw it, I’ve lost my brother, my husband, my dad…

The Unthanks, Elmet (Bradford, The Loading Bay). The wonderful Unthanks were performing live as part of this drama premiere for Bradford 2025, a dark and brooding play by Bradford writer/director Javaad Alipoor, about ‘family, revenge and the ultimate price of freedom’.

Bach & the American Minimalists – Shani Diluka: J S Bach, C P E Bach, Philip Glass, Keith Jarrett, John Cage, Bill Evans, Moondog, Meredith Monk (Crucible Playhouse). This was a brilliant concept, beautifully performed and presented by Diluka on piano. The programme interspersed pieces by Bach(s) with pieces by various minimalist composers, following on from one another so that we heard and felt the resonances between them.

November:

Quartet for the End of Time – Ensemble 360: Gideon Klein – String Trio, Leo Smit – Trio for Clarinet, Viola & Piano, Messiaen – Quartet for the End of Time (Crucible Playhouse). I can’t hear the Messiaen too often – it never feels familiar, and never fails to compel absolute attention. The story of the first performance is unforgettable too – a freezing January night in a POW camp in 1941, with the score scribbled on scrap paper scrounged from a friendly guard, and with instruments that were poor to begin with and hadn’t been looked after. And yet, and yet, the extraordinary music was extraordinary even in those circumstances. The Klein and Smit pieces are both small victories over Nazi brutality – their composers were murdered, and so we were deprived of all the music they would have written (Klein, especially, who was only 25 when they killed him), but we have these pieces, which weren’t meant to survive. But here they are.

Julian Jones (Cerrones). A nice deal: lunch at Cerrones (Italian restaurant), followed by a gig from Julian, playing guitar and keyboards, performing almost exclusively his own compositions apart from two covers (James Taylor and Neil Young).

Ravel & Glass: Cinematic Quartets – Piatti Quartet: Bernard Hermann – Suite from Psycho, Jonny Greenwood – The Prospector’s Quartet, Philip Glass – String Quartet no. 3 ‘Mishima’, Maurice Ravel, Quartet in F Major (Crucible Playhouse). A fascinating selection of pieces. Hermann’s Psycho Suite is stunning, absolutely riveting, and I was convinced when I heard the Ravel that he might have been influenced by it – can’t prove it, obviously, but I relistened to both at home a few days later, and felt the same, so that’s my theory that is mine.

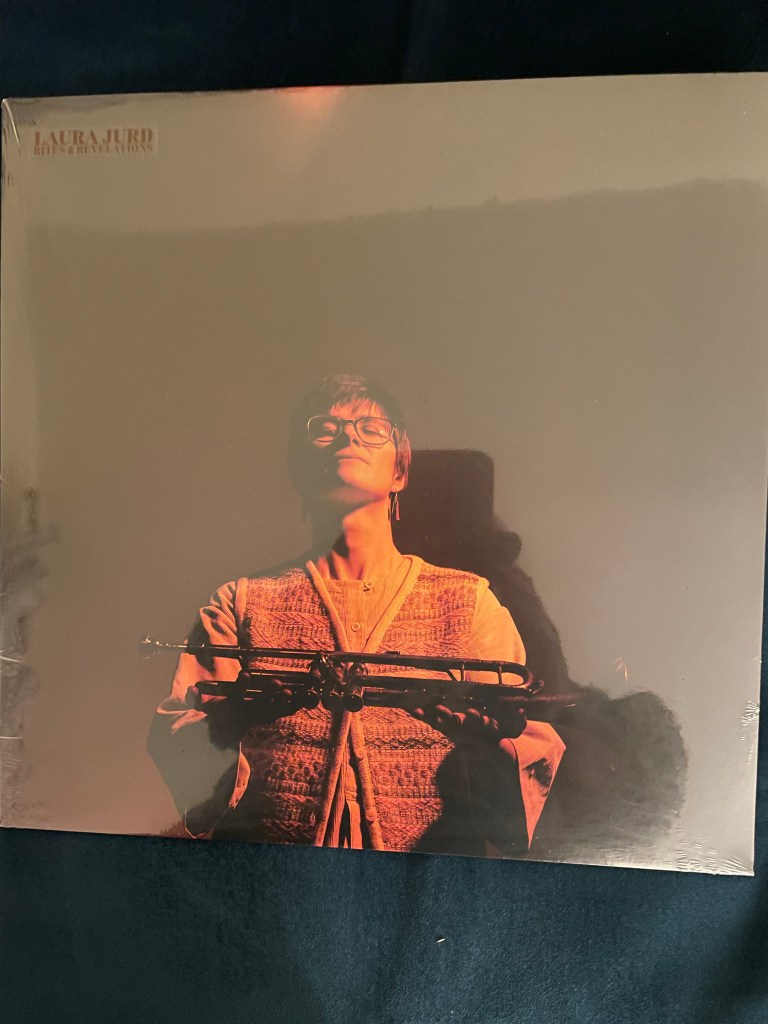

Laura Jurd Quintet, Sheffield Jazz (Crookes Social Club). The gig of the year from Sheffield Jazz, and one of the top few overall. An intriguing line-up – Laura on trumpet, obviously, and Corrie Dick on percussion, plus Ultan O’Brien on viola, Martin Green on accordion and Ruth Goller on electric bass. O’Brien and Green gave the music a folky feel, with a strong klezmer element at times, and I felt very strong Third Ear Band vibes. The Quintet were performing material from the latest album, Rites & Revelations, which I bought on vinyl after the gig, as I was so blown away by the music.

Gong (Crookes Social Club) – Gong are still here, undiminished in spirit if not in terms of the personnel who made those early albums. A lot of this is down to Kavus Torabi, who Daevid Allen specifically proposed as his successor to lead the band, and who makes a charming and charismatic front man, and a fine musician. (I already knew of Torabi through the delightful book he co-wrote with Steve Davies (yes, the snooker player), Medical Grade Music.) Long live Gong.

Death & the Maiden – Dudok Quartet: Saariaho – Terra Memoria, Gesualdo – Moro, lasso al mio diolo, Mussorgsky – Songs & Dances of Death, Liszt – Via Crucis, Schubert – Death & the Maiden (Upper Chapel). The Gesualdo, Mussorgsky and Liszt pieces were arranged for string quartet by the Dudoks. An uplifting evening of music about mortality. One of the musicians said at the start, that when we write or talk about death, we’re always really talking about life, and that makes sense to me. Certainly these pieces were poignant, moving, but never just heavy or dark – there was light, always light.

December:

Viennese Masterworks – Tim Horton: Haydn – Piano Sonata in E flat, Brahms – Four Ballades, Schoenberg – Suite Op. 25, Beethoven – Piano Sonata in D (Crucible Playhouse). This concert is part of a series that explores the connections between the First Viennese School (e.g. Haydn & Beethoven) and the Second (most notably Schoenberg, but also Berg & Webern). Here Brahms forms a kind of bridge between the two Schools. Schoenberg’s Suite is a Baroque suite, with a Brahmsian Intermezzo – clearly, as Tim pointed out in his pre-gig talk, the creation of twelve tone/serialism was not some scorched earth iconoclasm, but a development of this great musical history.

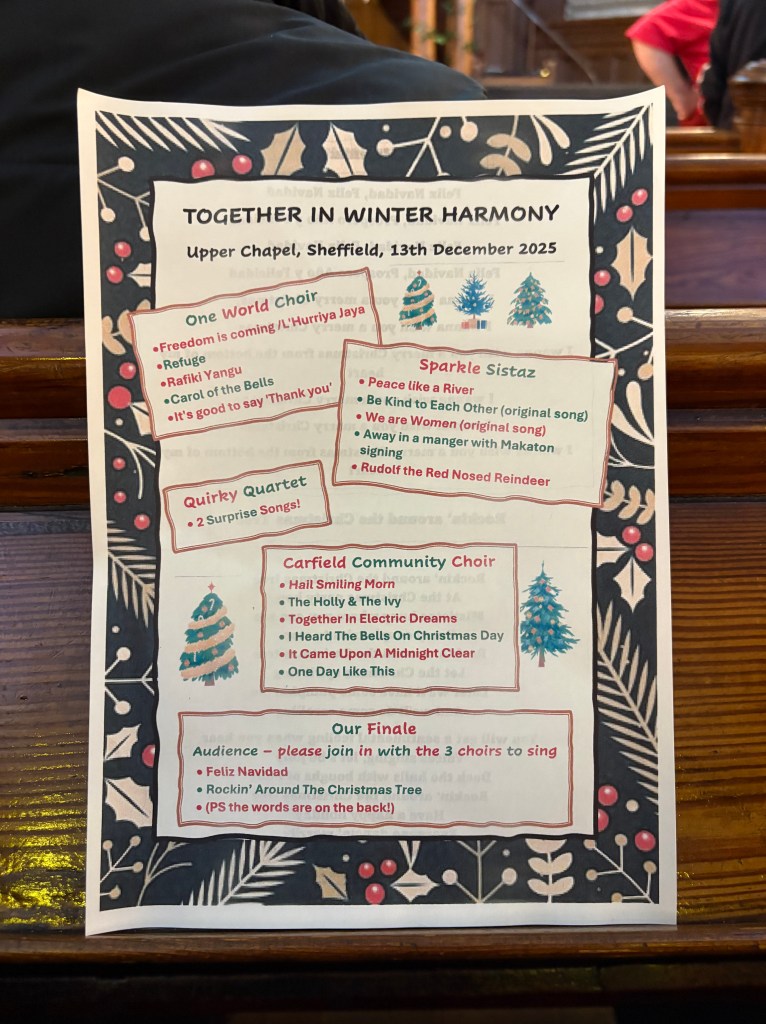

Together in Winter Harmony – Carfield Community Choir, One World Choir, Sparkle Sistaz (Upper Chapel)

Lovely festive choral concert. One World Choir brought us songs in various languages, Arabic, Ukrainian and a number of African languages, some explicitly Christmassy, others more tangential but uplifting. I was there primarily for the Sparkle Sistaz, who were magnificent, doing two of their own songs (I noted they didn’t do ‘the one about people who piss us off’ or ‘Bad Boyfriend’ which was probably for the best, as they’re feisty rather than festive) and some standards – notably a rambunctious version of Rudolf the Red Nosed Reindeer (a song all about difference, bullying and inclusion, is it not?), and performed with their usual sass and panache, and got a rapturous response.

Pass the Spoon – Opera North (Howard Assembly Room)

Absolutely bonkers comic sort-of-opera set on a TV cookery show, created by artist David Shrigley with music by David Fennessy (using lots of percussion, a nod to Bernard Herrmann’s Psycho score, and a quick burst of Für Elise, amongst other musical references). I wasn’t sure at first how much I was going to enjoy it, but it got darker and funnier and more and more bonkers as it went on – surreal, scatological and unhinged. Excellent fun.

Radio

I’m a Radio 3 sort of a chap. I know other radio stations are available, and always mean to put on Radio 6, but somehow haven’t got round to it. I know it’s an old person thing to grumble about schedule changes but I do still miss Saturday afternoons on R3, with Sound of Cinema, Music Planet, and Jess Gillam’s This Classical Life taking us nicely into the evening. Only the first of those is still on in the mid-afternoon slot and so despite best intentions (see above) I find I don’t catch up on Sounds with the other programmes very often. Similarly, the demise of J to Z has lessened my listening to jazz on R3, since its replacement is ‘Round Midnight which is on, as one might expect, around midnight, and thus way past my bedtime. I do have Jazz Record Requests on a Sunday afternoon and remain a loyal listener – there are always some tracks by artists I know and love, and some by artists I don’t know yet and would like to. And, each year since 2021, Alyn Shipton has played a request in memory of M (so far, Miles, Mingus, Holiday, Cobham, Peterson & Young for me, and John Marshall for M’s brother).

An innovation this year is my discovery of Radio 3 Unwind which, played through a pillow speaker, has been remarkably helpful in allowing me to get off to sleep and, particularly, to get back to sleep more easily if I wake during the night. M was always a bit scathing about the use of music to relax (he used to rant about Classic FM’s emphasis on this role for music), and he could not use music as background (thus on long drives he preferred R4, because he could more easily filter words out than music, whilst I’m the other way around). For me, the mix of ambient sounds, the shipping forecast and tranquil music allows me to filter out the endless whittling and catastrophising that my brain insists on, especially at 3 a.m. It works, anyway, and I’m most grateful for it.

Music Nights

As usual, what I choose to grab from the collection is either random, or prompted by something I hear or read. This year, I also had a batch of vinyl rescued from obscurity and mould in the cellar, amongst which were many things that we’d never replaced with CD and which I was hearing for the first time in more than 40 years.

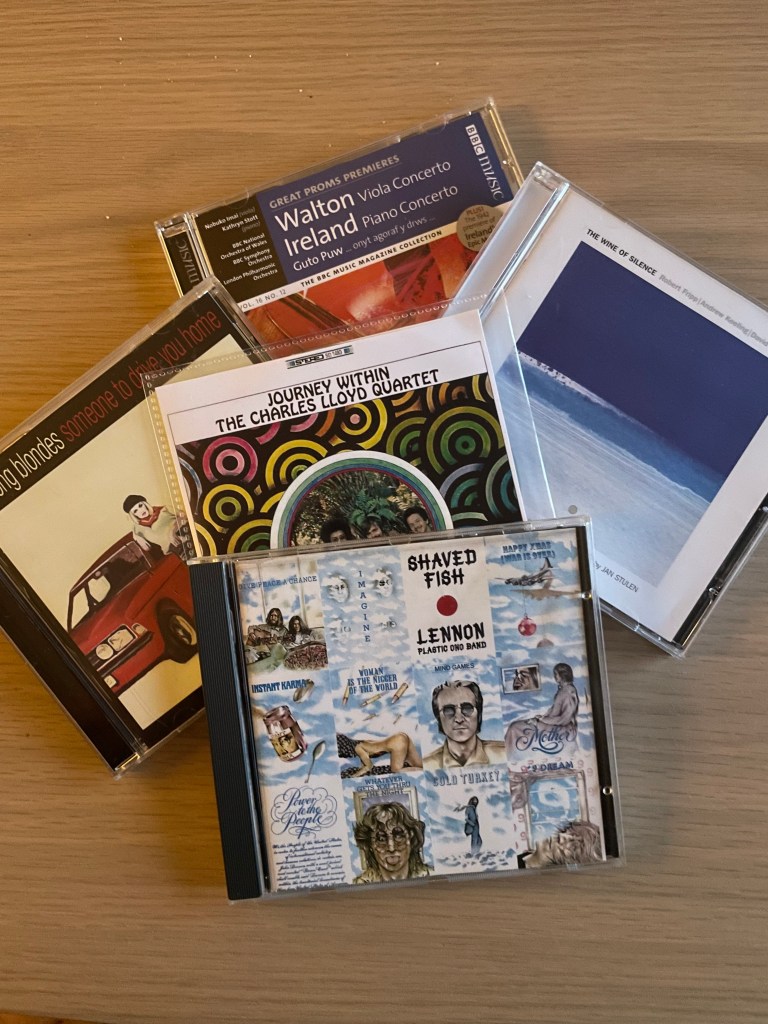

Those departed artists who were honoured through inclusion in my music nights include Brian Wilson, Gilson Lavis (Squeeze), Jack DeJohnette, Terry Reid, Ozzie Osbourne, Rick Buckler (Jam), Cleo Laine, Danny Thompson, Garth Hudson (The Band), Mani (Stone Roses), Steve Cropper (Booker T & the MGs) and Dave Ball (Soft Cell). And I marked the 25th anniversary of the death of the marvellous Kirsty MacColl with an evening of her music.

I post about what I’m listening to on BlueSky these days (I still have a look on X but I don’t feel I want to engage there, other than with Radio 3 and particularly Jazz Record Requests, who are still using the Musk place) and sometimes on Instagram/Facebook too. This makes me feel less like I’m listening alone. It is rare that someone doesn’t like and/or comment on my music posts – thank you to all who do so. I’m sharing the music I’ve chosen and it’s lovely to find that someone somewhere is nodding or smiling at my choices, or suggesting other things I might like, or reminiscing about what that track or album means to them. The other reason I share it is that M taught me to listen mindfully (though he wouldn’t have used that word) – not just to passively let the music play but to be aware of it, focus on it, think about what it’s doing and how. I found it hard at first to do that without him, but I’m getting the hang of things now.

I’ve also got some pretty hefty Spotify playlists, most notably the 13+ hour selection we put together for M’s wake, which features at least a smattering of the music we listened to together over 47 years. I play that one on our wedding anniversary, on the anniversary of his death, on his birthday, or whenever, really, because the music is absolutely bloody marvellous. It’s not ‘wallowing in misery’ when, even if one track makes me cry, the next makes me smile or forces me to have a bit of an awkward dance around the living room. It’s honouring him and our life together, triggering so many memories, and reminding me of other music I want to hear again, including new music that I’ve discovered or acquired since he died. There’s another playlist for Christmas (as free as possible of the usual suspects), and one for New Year featuring a selection of tracks that have some connection to events in the year, the one I made for my Dad’s funeral that never got played at the reception because I was having a massive dizzy spell just when I should have been loading up Spotify, and the one I made for a reunion with people who were at college with M that didn’t work on the night…

All of the artists below found their way on to my CD player or turntable, or I watched them live on TV, or listened on Spotify (but inclusion means that it was more than one or two random tracks).

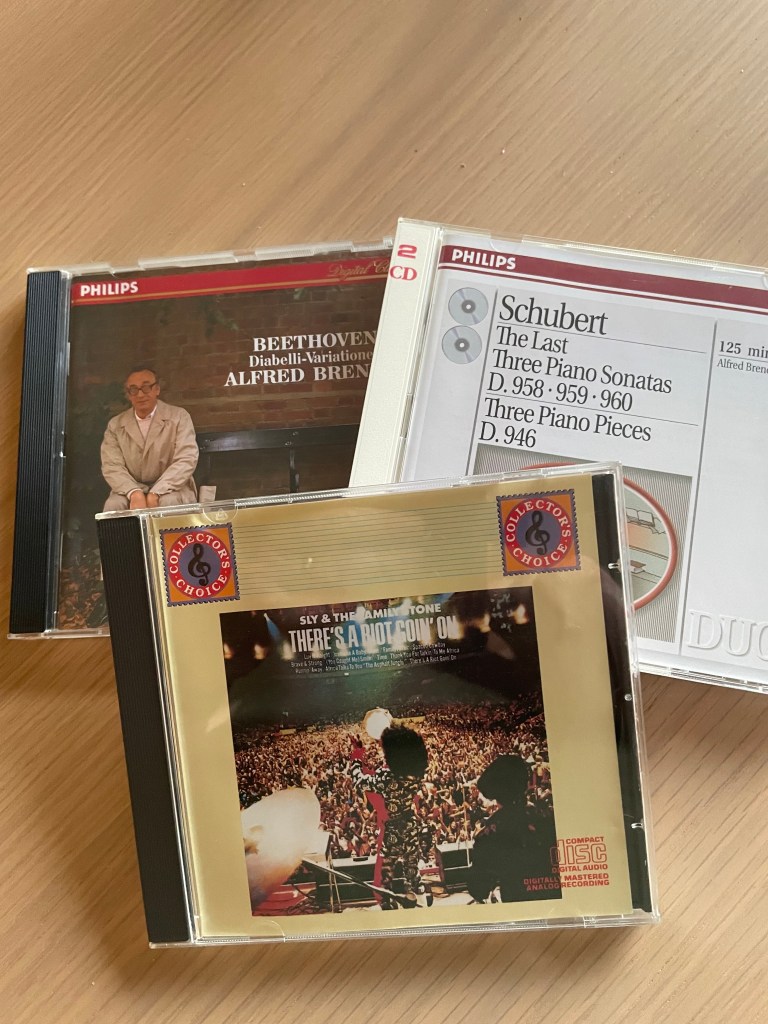

Yazz Ahmed, Jan Akkerman, Allegri, Amadou & Maryam, Amaarae, Multatu Astatke, J S Bach, Badfinger, Chet Baker, the Band, Bartok, Beababadoobee, Beach Boys, Beatles, Beethoven, Black Sabbath, Black Uhuru, Booker T & the MGs, Bowie, Brahms, Bruch, Kate Bush, David Byrne, Camel, Brandi Carlisle, Chakra, Chitinous Ensemble, Chopin, Gary Clark Jr, Coltrane & Duke, Corelli, Cymande, Delius, Corrie Dick, Elgar, Ellington, Empirical, En Vogue, Ezra Collective, Donald Fagen, de Falla, George Fenton, Ibrahim Ferrer, Ella Fitzgerald, Fripp Keeling & Singleton, Gateway, The Gentlemen, Stan Getz, Egberto Gismonti, Philip Glass, Global Village Trucking Company, Gong, Grande Familia, John Grant, Stephane Grappelli, Grieg, Haim, Handel, Hatfield & the North, Haydn, Hendrix, Henry Cow, Bernard Herrmann, Highlife, Steve Hillage, Zakir Hussain, Indigo Girls, John Ireland, The Jam, Etta James, Keith Jarrett & Jack DeJohnette, Keith Jarrett Trio, Laura Jurd, Villem Kapp, Seckou Keita & Catrin Finch, Graham Kendrick, Nigel Kennedy & the Kroke Band, King Crimson, Tony Kofi & Alina Bzhezhinska, Cleo Laine, Led Zeppelin, Michel Legrand, Jon Leifs, Libertines, Charles Lloyd, The Long Blondes, Baaba Maal, Kirsty MacColl, Madness, Manhattan Brothers, Bob Marley, Winton Marsalis, Mendelssohn, E T Mensah, Mingus, Joni Mitchell, Monochrome Set, Moondog, Christy Moore, Alanis Morissette, Mozart, Jalen N’dongo, Youssou N’dour, New Jazz Orchestra, New York Dolls, Newstead Abbey Singers, Paganini, Palestrina, Part, Pentangle, Esther Phillips, Plastic Ono Band, Pulp, Guto Puw, Ravel, Raye, Terry Reid, Django Reinhardt, Max Roach, Rodgers & Hammerstein, St Vincent, Satie, Schoenberg, Schubert, Schumann, Scissor Sisters, Self Esteem, Shaboozey, Caroline Shaw, Shostakovich, Sly & the Family Stone, Soft Cell, Songhoy Blues, Fela Sowande, Springsteen, Sprints, Squeeze, Steel Pulse, Stone Roses, Sugababes, Summers & Fripp, Swingle Singers, Tchaikovsky, Troubadours du roi Baudouin, Eduard Tubin, Vaughan Williams, Vivaldi, Walton, Marcin Wasilewski Trio, Debbie Wiseman, Working Week, Robert Wyatt, Neil Young

2025 On Screen – the Second Half

Posted by cathannabel in Film, Television on December 14, 2025

Film

None of the films below were seen at the cinema. This is not normal, and I need to do something about it. Apart from anything else, I should be getting more value from my Showroom membership than I have for the last six months! I like the whole experience of going to the cinema – it’s so easy to put on a film on Netflix or whatever and half-watch it whilst scrolling on the phone, pausing to go and make a coffee or take a phone call, etc. The ritual of cinema – putting one’s phone on silent and away in a bag for the duration, stocking up on snacks and drinks beforehand to last for the duration, and all of that – makes one focus on the film, in a way that helps when trying to gather one’s thoughts about it after the credits roll.

Nonetheless, there were some fine films on TV, including some that I’d intended to see at the cinema but missed. I only realised whilst preparing this blog how few of the films below were produced/directed by women. Only Autumn de Wilde, with her debut, Emma., Wendy Finerman, producer of The Devil Wears Prada, Mia Hanson Løve with One Fine Morning, and Celine Sciamma, collaborating writer on Paris 13th District. Because these are films I’ve watched because they were there, rather than films I’ve chosen to go out of the house and into town to see, I can’t draw too many conclusions about this batch, other than to say that I clearly have watched quite a lot of thrillers, and not a lot of comedy, which seems pretty typical. I think there were one or two films that I started and gave up on – I haven’t included these because I suspect there may have been a ‘me’ problem – mood, level of tiredness, that sort of thing – rather than it necessarily reflecting badly on the film.

5 September

Compelling and extremely tense account of the terrorist attack on the Israeli team at the Munich Olympics in 1972, through the eyes of the ABC news team on the spot, who were providing live coverage of the sport, and found themselves confronting instead the practical and ethical challenges of live coverage of an unfolding tragedy. It’s understated in a way that actually enhances the tension rather than dissipating it.

American Gangster

Denzil Washington is superb here. I’m not a Russell Crowe fan but he’s pretty good in this too – he has to be, to make us root for him rather than the bad guy who happens to be Denzil Washington.

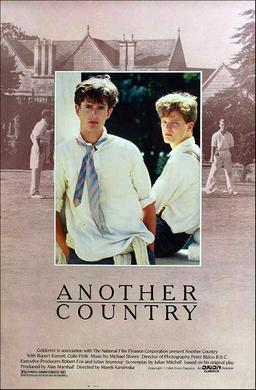

Another Country

Beautiful – and I’m not just talking about the male beauty on display from Rupert Everett, Colin Firth and Cary Elwes. Ultimately though I wasn’t convinced by the bookend pieces with Everett as an older Bennett (in rather poor ageing prosthetics) being interviewed in Moscow about why he betrayed his country. We were supposed, I think, to see how the double life he realised he would have to lead as a gay man prepared him for the double life of espionage, but I don’t think this was developed enough to really work. I also find myself a little weary of posh boys – gay or straight – at posh schools.

The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes

I was slightly underwhelmed by the book but rather enjoyed this. It’s a tad too long, and – this is a me problem – there are WAY too many snakes. I know the title announces it, and I remember the snakes from the book, but I much prefer not to actually see them… Rachel Zegler is great as Lucy Gray – there’s always a steeliness in her that belies her doe-eyed charm.

The Devil Wears Prada

Very enjoyable, even if it does its best to have its cake and eat it (not that eating cake is an appropriate metaphor given the food-phobic culture it portrays). It’s funny, and Meryl is awesome, suggesting depths and complexities without spelling everything out. As far as plausibility goes, I’m not qualified to comment, though the notion that Ann Hathaway’s Andy, a woman who prioritises comfort and wears sensible shoes, can learn not just to walk but to run in vertiginously high heels on that time frame seems to me improbable.

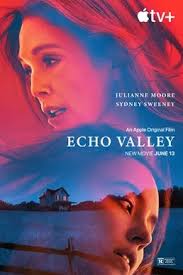

Echo Valley

A great cast make this highly enjoyable and genuinely tense but can’t quite paper over the plot holes. I found myself trying to work out the timings for what actually happened once we’d had the reveal, and I couldn’t quite make sense of it. It’s such a common failing in thrillers, to leave the revelations and resolutions to be dealt with in a mad rush at the end, perhaps hoping we will be swept along and not notice… Old fashioned whodunnits, the sort where the detective gathers everyone in the library to announce the guilty party, used to have a sort of coda where someone says, ‘but what I still don’t understand is’ (speaking for all of us, probably) and then the detective helpfully explains. I am happy for things to be left unexplained, for plot threads to be left dangling, for motivations not to be clear even as the credits roll, but I don’t like plots that seem to suggest that everything is resolved, without making absolutely sure that the resolution makes sense. NB this will be a recurring theme…

Emma.

Having recently seen the Paltrow version, I think I prefer this. It’s funnier, for one thing, Anya Taylor Joy is quirky and Johnny Flynn’s Knightley is rougher around the edges than some portrayals. As enjoyable as it is, I remain unconvinced, however, that we need any more Austen adaptations, unless someone is prepared to tackle the less popular ones (Mansfield Park or Northanger Abbey).

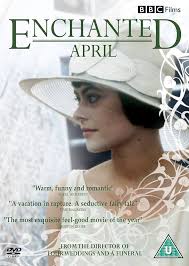

Enchanted April

Delightful – Josie Lawrence and Miranda Richardson lead as two not so happily married middle-class women who, entirely out of character, seize the chance to escape to a castle in Italy, where the place works a kind of magic on them, and the people who share it with them. That sounds a bit soppy and I suppose it is, but it’s also very funny, and very touching. By chance, I was watching Miranda Richardson in TV drama The Last Anniversary (see below) on the same day, and feel compelled to say that she is even more stunningly beautiful now than she was back in 1992. And the film has a place in my heart as it’s set and filmed in Portofino, where my daughter got engaged the summer before last. Maybe it is a magical place.

Frankenstein

Of course there have been many, probably too many, adaptations of Shelley’s novel, some of which bear only a passing and superficial resemblance to her narrative, let alone her philosophical concerns. I was never going to skip this one, given that it’s produced/directed/written etc by Guillermo del Toro, who was responsible for two of my favourite films, Pan’s Labyrinth and The Shape of Water. It’s so long since I read the book that I can’t swear to the film’s fidelity to the plot but it felt broadly faithful (though was the monster impervious to bullets in the original?). It’s visually fantastic, of course, gothic and melodramatic and (as the Guardian reviewer put it) ‘monstrously beautiful’. As is Jacob Elordi as the monster, to whom del Toro hands over the narrative part way through. Frankenstein’s contempt for his own creation – because it fails to live up to his impossible ideal – is the monstrous heart of the film, echoing Victor’s own rejection by his father, and driving the tragic outworking of the plot.

The Gangs of New York

This has many brilliant moments but I found it wearyingly long. DDL, in this as in There Will be Blood, seems to be hamming it up to the max. Having watched the documentary series Mr Scorsese, I do get (I think) something of what he was going for, the past that was still tangible on the streets where he grew up.

The Good Liar

Mirren and McKellen in a drama whose twists and turns aren’t impossible to guess (and if one consults the cast list in IMDb as I did, one of the major twists is substantially given away). But never mind all that, they are both splendid, as one would expect – it’s a kind of duel where we are supposed to think at first that they are very mismatched, but (as I hoped, being a fan of dramas where older women are shown to be canny and capable) all is not as it at first seems. It’s often very funny, but with an undercurrent of sadness.

King Richard

Will Smith’s excellent performance as Richard Williams, father to Serena and Venus, gives us room to wonder if he is an entirely reliable narrator, without leaning too much into that idea. He is both utterly unreasonable, and right in his assessment of how far his daughters could go, and of the obstacles that might be in their way.

The Lost Bus

A gripping account of a true story from the 2018 Camp Fire disaster in California, when a driver doing the school run found himself trying to get 22 children and their teachers (the film only portrays one teacher as the other did not want to be included) to safety as the fires destroyed everything in their path. It’s directed by Paul Greengrass, notable for United 93, 22 July (about the 2011 Norway attacks) and Captain Phillips. The suspense here is perhaps lessened by the fact that we may well know that the bus got through, but nonetheless it is incredibly tense, and Matthew McConaughey and America Ferrera are great as the two adults trying to calm and reassure the kids in the face of their own terror, for themselves and for their loved ones.

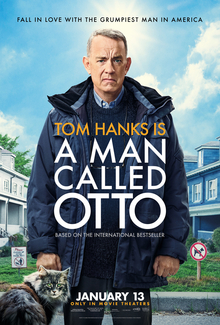

A Man Called Otto

This could have been merely soppy – massively grumpy old curmudgeon has his miserable heart warmed by a lively young family who move in across the road – but the script and the performances give it much more than that, the heartbreak of loneliness, dark humour, and some genuinely moving moments. A lot of that is down to Hanks of course, this is the sort of thing he’s so very good at.

Maria

This can be seen as one of Pablo Lorrain’s trilogy of portraits of women on the edge: Jackie (Kennedy), Spencer (Diana) and now Maria Callas. We start near the end of her life, her voice has lost its control and power, and her ‘medication’ leads to hallucinations and confusion. We get flashbacks to her earlier life, both pre-fame and during her heyday as the diva of divas. Angelina Jolie is superb. I’m not qualified to speak of its accuracy – and I’m sure there was much more to Maria herself than the film could convey – but it’s a powerful and moving portrait.

Mr Burton

An old-fashioned sort of film, really. Performances are great – Toby Jones’s Mr B is melancholy but positive, easily wounded, and Richard to-be-Burton is bumptious and arrogant but also wounded. It doesn’t directly ask the question of whether Mr B had homosexual inclinations, but it shows how other people were ready to insinuate that to explain his motivation for taking Richard under his wing. For me, whether he was a closeted gay man or not, it seems clear (from the film and other sources) that if he was attracted, he was also scrupulous about not exploiting his influence or his proximity. Harry Lawtey gives us a flavour of Burton the star, and it’s fascinating to see that emerge, along with that extraordinarily rich voice.

Night Always Comes

One of those narratives where the protagonist is trapped due to bad decisions, which leave him/her with only bad choices (it reminded me of Martin Freeman’s TV drama, The Responder, for example). Vanessa Kirby is compelling, even whilst one wants to shout at her when she’s making the aforesaid bad decisions and getting herself deeper and deeper into the mire.

One Fine Morning

A rather fine study of a woman dealing with her father’s dementia (I wonder why that resonated with me…) and of what reviewer Monica Castillo called ‘a quiet sense of devastation’. Mia Hanson-Løve is skilled at this (I’ve seen a couple of her other films, Father of My Children, and Things to Come, both of which were excellent). Léa Seydoux is brilliant at conveying the pressure Sandra is under, as a widow with a young child and an increasingly dependent father, who knows she isn’t doing enough but can’t do more.

Our Town

I tracked this down on YouTube after reading Ann Patchett’s marvellous Tom Lake, which centres on performances of this play (see my Books blog). The version I saw was a TV film of a stage production, with Paul Newman as the Stage Manager. I thought at first it was going to be a bit too folksy American for my taste but then it got darker and deeper and by the end I was all in and weeping. It resonated with my thoughts about mortality since my husband died, and about how we go through our lives focusing on the big important days but don’t ever ‘realize life while [we] live it, every minute’. I won’t go on but the play now has a place in my heart.

Paris – 13th District

Jacques Audiard working with Céline Sciamma! Audiard directed one of my favourite contemporary French films, The Beat That My Heart Skipped, as well as A Prophet, and Sciamma is responsible for Girlhood, Petite Maman, and Portrait of a Lady on Fire (and Paris – 13th stars Noémie Herbert, who’s in that last film). It’s a funny, touching film, a lot less harrowing than the aforementioned Audiards or Sciammas, about young people connecting (sometimes through misunderstandings) and disconnecting.

Persuasion

My favourite Austen (see my books blog for comments on Mansfield Park, which I recently re-read). I loved Persuasion even as a teenager, when one might expect to be more drawn to some of her feistier heroines, but Anne Elliott moved me a great deal then, and even more so now. A lot depended, as in any film adaptation of a loved book, on the casting, and both Amanda Root and Ciaran Hinds were perfect. They are the still centre of the film, around whom people are gossiping, chattering, generally making themselves heard and seen, but who themselves say little (at least out loud). Once they have, quietly and unobtrusively, sorted out their future together, they walk out into Bath, where a circus is in town and people are cartwheeling and prancing around them, as they are oblivious to it all. It’s beautiful.

Rwanda

I really don’t know what to make of this, or why it was made. We have white Italian actors on stage playing the roles of people caught up in the Rwandan genocide and then segueing into scenes with Rwandan actors playing the same roles. The blurb in IMDb reads: ‘Close your eyes and try to imagine. A man, a woman and their families. The fastest and most systematic genocide in history. He is Hutu, she is Tutsi. He must kill. She must die. A fate similar to many others in that bloody spring. But this time there is a slight difference. When you open your eyes, you will be in their shoes and now the choice is yours. And yours alone’. None of which really gives us a convincing rationale for the way the story is framed: it creates confusion, and all that the use of white actors does, in my view, is to wrench us away from the real, tragic, horrifying events every time they appear.

Small Things Like These

Based on the Claire Keegan novel, like The Quiet Girl (from the book Foster), this is an understated, quiet film that gets under your skin and straight to your heart. Cillian Murphy is excellent, and the film does a remarkable job of conveying a sense of threat from what might seem an unlikely source. Directed by Tim Mielants, who also directed…

Steve

Cillian again, and again he is wonderful. This is a brilliant, downbeat, subtle film that very effectively conveys both the barely contained chaos and mayhem of the troubled boys and the commitment and love mingled with despair and boiling frustration of their teachers. The establishment itself is under threat as a waste of resources, and as much as the boys are full of swagger and aggression we see and feel how lost they will be if they lose this haven. I was unequivocally rooting for Steve and his colleagues, and for their charges, which made the film both extremely tense – towards the end especially, when I was full of dread – and very moving.

The Straight Story

This reminded me rather of Perfect Days. A synopsis of the plot would make it sound rather dull, but it is completely engrossing and very moving; subtly so, it doesn’t present itself as ‘heartwarming’ although my heart did feel definitely warmed, nor as tearjerking, though I did have a bit of a weep. Richard Farnsworth is wonderful in the lead role. I have to confess I’m not familiar with much of David Lynch’s oeuvre – I liked The Elephant Man and Wild at Heart, was not a fan of his Dune, and switched off Blue Velvet quite early on – but this one is near perfect.

Surge

Ben Whishaw is outstanding here as a man with mental health problems whose life spirals out of control as he tries to free himself of the constraints of job and family. It’s a very uncomfortable watch precisely because Whishaw makes us care about this man, so one spends a lot of time thinking, ‘Oh no, please don’t do that, please…’ and then watching as he does whatever it is that is bound to make matters infinitely worse. It’s deeply compassionate and rather moving.

Tar

This is brilliant. A film that treats its audience as adults who can manage to hold more than one idea in their head at the same time, and can engage with theoretical, intellectual discussions about music and its performance, with a compelling performance from Cate Blanchett in the title role.

The Thursday Murder Club

I haven’t read the book(s) so can only judge the film as it stands. It was mildly enjoyable, mildly diverting. Some of the scenarios were too ludicrous to be really funny, and some of the characters were a bit hard to take as representations of people only a little older than me (Celia Imrie’s wardrobe seemed to have been purloined from my Gran – born 1901 – rather than what a well-heeled woman in her mid-seventies in 2025 would be likely to wear). Daniel Mays seemed here to be reprising his character as the bumbling copper from The Magpie/Moonflower Murders. It didn’t make me want to read the books, but it passed a couple of hours quite well.

Unstoppable

Classic set up – a driverless train is hurtling across the countryside, and must be stopped before it reaches a residential area – delivered with conviction and panache by Denzil Washington and Chris Pine as the maverick pair who have to stop the unstoppable train. It’s actually a true story, remarkably.

Vera Drake

Imelda Staunton is outstanding in this. She cares for and about people, in practical ways, and providing illegal abortions for girls ‘in trouble’ is simply an extension of that. She never uses the A word, any more than she speaks of what got these girls and women into ‘the family way’. Just tells them to pop their knickers off and that ‘it will all come away’ when they go to the loo. Of course this is a gross over-simplification, as she finds out when one of her girls is critically ill after the procedure. She feels shame at her exposure but holds on to her belief that she is just helping out. It’s a corrective to the image of the back-street abortionist as exploiting these girls for financial gain and with no concern for the consequences to them, even if we wince at Vera’s haphazard approach to clinical hygiene.

TV

As usual there were a lot of murders. More than are listed here, since I haven’t reviewed the latest outings for Shetland, Trigger Point, Beck, The Gone, Karen Pirie or the Sommerdahl Murders, though all were watched and enjoyed, as were the latest series of Slow Horses and The Diplomat. There were a fair few thrillers that I gave up on or even watched through to the end but couldn’t think of anything worth saying about them other than to reiterate the kind of complaints I make about several better offerings below.

Because of the general murderiness, I find it’s essential to have a few things that are safe, that you know aren’t going to let anything too horrific happen, and that in general allow redemption for even the least likeable characters. This half-year that role was played by the latest season of All Creatures Great & Small, Leonard & Hungry Paul, and A Man on the Inside (I haven’t reviewed that last, because it’s season 2 and essentially the same sitch, just transplanted to a college rather than a retirement home, but I enjoyed it).

Blue Lights is my top cop drama, and Paradise the top thriller. Other standouts this half-year were The Line (Un Village Francais) and Stranger Things‘ final season.

I’ve tried not to do spoilers but you proceed at your own risk.

Drama

All Creatures Great and Small

I didn’t originally intend to review this, because it’s an ongoing series (and a remake), but I find myself referencing it as the epitome of nice telly and, particularly after the finale of this latest season, it is both that and more. The central three characters are much as they were in the 1970s series, although Siegfried is given more of a back story to explain his eccentricities, and Tristan is given more depth, particularly in the latest episodes where he finally opens up about some of what happened to him on active service. The female characters now actually have characters, which is a good thing. Mrs Hall in particular has gone from being a stock character – stout, sensible housekeeper – to someone much more interesting, much deeper. And as I mention above, whilst – as far as I recall – in the 1970s version WW2 was a kind of hiatus, here it deeply affects everyone, whether they are mothers/wives waiting for news which, in some cases, when it comes is desperately sad, or the men who volunteer and come back different. It’s nice telly in that we can trust that nothing too horrific is going to happen to the people of Darrowby, no serial killer is going to stalk those lanes and moors, the body count is going to remain low, with most of those who die doing so at the appointed time in their beds. But it’s more than nice in that these people have depth and complexity and so we invest in them, and what happens to them moves us more. It’s beautifully acted, of course, most particularly Anna Madeley’s Mrs Hall who is responsible for a large proportion of the moments that make me weepy, Sam West’s Siegfried, and Patricia Hodge’s Mrs Pumphrey (she had a hard act to follow in Diana Rigg but she’s given the character – who could be a bit of a joke – greater depth).

The Assassin

There are a number of actors whose presence in a series always inclines me to watch (and a few whose presence has the opposite effect, but we won’t dwell). Keeley Hawes is one in the former category, ever since Life on Mars and Line on Duty proved her versatility, and I thoroughly enjoyed this, despite its startlingly high body and gore count. The humour is, obviously, very dark, but it’s well done, and Hawes makes her ‘retired contract killer being forced to brush up her murdering skills’ human, and makes us root for her (and even her rather annoying son).

Blue Lights

This started off extremely well, and now with the third season is even better. What marks it out initially from the mass of police dramas is the Belfast setting, where organised crime and dissident paramilitaries have merged into an ever-present threat to the peelers. But what makes it outstanding is the quality of the writing and the performances – there are a number of incredibly high-tension scenes in this season, where the tension comes not only from the situation but from the fact that we’re so invested in the characters. Excellent, excellent stuff.

Bookish

So-called cosy crime series, set in 1946. I can’t be doing with too much cosiness – if we’re talking about murder, there has to be some sense of threat, of evil, of tragedy. Bookish does provide those things, along with humour and heart, and this first season ended with a promise of more.

Borderline

On the face of it, just yet another mismatched cop duo, but which has added interest due to the fact that these cops work either side of the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, and have to work together when Irish bodies turn up in the North, or vice versa. The Garda cop is rather tiresomely obnoxious, though her back story does provide some explanation for this. The Northern Irish cop has his own quirks – recovering alcoholic, so common in these narratives that it hardly counts as a quirk, but also a religious faith that is shown as being profound and central to his life, which is much more unusual.

Classified

Dizzying twists and turns in this French-Canadian thriller about a mole in the Canadian secret services, and the tensions between them and their US counterparts. I’m not sure that I quite grasped it all but that’s down to me occasionally losing concentration and missing info in the subtitles, I suspect, rather than to the plot/script.

Coldwater

Way, way over the top, but sort of fun. Seeing Andrew Lincoln, who never flinched in the face of zombie hordes, being a bit of a wuss, is amusing. Eve Myles does a good job of being a bit dodgy here, as she does in The Guest (see below) but Ewan Bremner’s Tommy is so obviously bonkers that it’s a bit hard to credit no one has sussed him out. The ending leaves a number of threads loose, but I kind of hope they don’t feel the need for another series.

Cooper & Fry

Adapted from Stephen Booth’s Peak District set series, many of which I’ve read. I enjoyed the books, but I don’t remember quite such a heavy reliance on the folklore/superstitions of the area. In the first two episodes alone we had a Screaming Skull, a Hand of Glory, a Plague Stone and a Black Dog, and a predictable tension between the city cop and the locals about how seriously to take these things. Otherwise I quite enjoyed the series, though it doesn’t really stand out from the crowd.

Down Cemetery Road

An adaptation of the first in Mick Herron’s other series (Slow Horses continues to be brilliant both in book and telly form), with Zoe Boehm (played – wonderfully – by Emma Thompson) as his lead detective and playing alongside the always excellent Ruth Wilson this is definitely a winner. The dialogue crackles with wit and the tension and stakes are nailbitingly high.

Fatal Crossing

Danish cold crime – a cut above the average. It leaves questions still hanging in the air, about the why, if not the who.

The Forsytes/The Forsyte Saga

I have history with the Forsytes. I watched the 1967 series – it must have been the Sunday night repeat which launched in September ’68, when I was 11. I was completely spellbound. I have no doubt if I rewatched it I would have issues, but it was truly powerful television, with some scenes that I can still bring to mind today. I watched the new Channel 5 adaptation with some trepidation, and rising annoyance at completely unnecessary plot changes, which radically alter the dynamics between characters, and at some of the casting. Soames, Young Jolyon and Bosinney could be members of a boy band – all are blandly handsome but characterless. We are treated to scenes of Young Jolyon shirtless in the gym, abs glistening, floppy hair artfully tousled. Even Soames has abs and biceps for heaven’s sake, as we saw in the scene of his wedding night with Irene.

I found the 2002 series on Netflix and rewatched that, which was much more satisfying. Damien Lewis is outstanding as Soames and Gina McKee conveys Irene’s self-contained, cool distance very well (unlike Millie Gibson’s giggly girl – not blaming Gibson, it’s the script & direction that’s the problem). It stays pretty close to the books in terms of plot (with some inevitable streamlining and trimming of peripheral characters).

There’s really no comparison between the adaptations, but I daresay I will continue to hate-watch the C5 version just to see how they deal with some of the plot developments, even if it irritates me enormously. If this was called, I don’t know, The Bridgertons or The Downtons, it would be soapy fun, but they are laying claim to John Galsworthy’s characters and if I were JG I’d be figuring out how to haunt everyone who dreamt up this mess.

Frauds

Suranne Jones and Jodie Whitaker are superb as two ex-con artists who team up for ‘one last job’. It’s funny and touching, and I would watch these two in anything.

The Gold

I’d skipped this when Series 1 aired a while back, but having been told very firmly by friends whose judgement I trust that it deserved to be watched, I then binged it and had not a moment’s regret. Splendid performances, very well written, an admirable avoidance of clichés and stereotypes. I very much liked Hugh Bonneville’s Boyce, who managed to convey both a downbeat stoicism and an absolute driving commitment to solve the case, but Tom Cullen’s portrayal of John Palmer is outstanding.

The Guest

This goes from 0 to 90 in the space of one episode – improbabilities pile up and really, the only way to approach this is just to suspend disbelief and go with it. I don’t mind this over the top approach as long as it’s well done, even if it is silly.

The Hack

Fascinating, if perhaps a little longer than it needed to be. There are two strands, which come together in the later episodes – David Tennant as the journalist who investigated and uncovered the phone hacking scandal at the News of the World, and Robert Carlyle as the detective investigating the murder of Daniel Webster. It generates much righteous indignation, but inevitably the outcome is frustrating – the News of the World might be history but there is no shortage of disgraceful journalism these days, and the Daniel Webster case remains unsolved.

Hostage

Here my fave Suranne Jones is PM, wrestling with various domestic and international crises, one of which results in the kidnapping of her husband in French Guiana. Julie Delpy is great as her French opposite number. Entertainingly balances suspense and political intrigue.

I Fought the Law

The true story of Ann Ming, who ‘fought the law’ to get justice for her murdered daughter Julie, with Sheridan Smith (in a classic Sheridan Smith performance) as Ann. Obviously the heart of the drama is the personal tragedy and trauma of the murder and its aftermath (Ann Ming was the one to discover her daughter’s body, after the police had failed to do so despite allegedly intensive searches of the house), but there’s also a fascinating legal thread about the concept of double jeopardy, which Ming was instrumental in overturning.

Insomnia

This was quite eerie and disturbing, but it got less plausible as it went on and the final episode packed way too much in at the expense of any deeper examination of character or motive. We were left, ultimately, with the only explanation being the least plausible one, and with the impact of the events particularly in that final episode being seemingly glossed over. And the final, final shot, actually made a nonsense of that implausible explanation (I’m trying very hard not to spoilerise here). The performances were good though, from Vicky McClure, Tom Cullen (see above re The Gold), Leanne Best and Lyndsey Marshal.

The Invisibles

I saw this described as a French Slow Horses, which it isn’t. It’s about a unit that investigates unidentified corpses, and it’s enjoyable, if a bit formulaic.

The Last Anniversary

There were good things about this, but many of them were squandered in a rushed ending where the mystery was supposedly solved but in a way that strained credulity beyond breaking point (see Insomnia, above), and then strained credulity again with a cheesy resolution where everyone was somehow absolutely fine all of a sudden and everything was nice. It was fun along the way, and it was lovely to see Miranda Richardson, and also the brilliant Danielle MacDonald (loved her in The Tourist).

Leonard & Hungry Paul

I was recommended to watch this as an example of gentle TV and I’m glad I did. I watch a lot of murdery TV, and a lot of heavy documentaries, and I need to mix in a bit of TV that might warm rather than chill my heart, that’s funny and touching and, I suppose, nice. All Creatures (the current version) is usually my go-to in this category (see above), but it’s good to have some other sources of niceness. It’s not enough just to be nice, of course, for it to be worth watching the writing has to be good, the characters have to be well-written and well-played, and there has to be some depth in there, some emotional heft. Leonard & Hungry Paul ticked all those boxes.

The Line

This is Un Village Francais, which I’d heard about but not found until v recently, thanks to the change of title. The line referred to is the demarcation line between the Occupied and Unoccupied zones, and the complicated nature of that demarcation (the Vichy government, enthusiastic collaborators with the Nazis, were in charge in the unoccupied zone so it wasn’t a haven of freedom or democracy) is portrayed very effectively. That’s the strength of this series. Because it takes a soap opera format, our core characters over seven seasons encounter all aspects of the Occupation, and how they cope with it – try to survive it – is portrayed in a subtle and nuanced way. Very few collaborate out of conviction, most out of expediency. Almost all have compromised, and so people we have admired and respected over six seasons may be on trial in the seventh. I have to admit that the seventh season was problematic, not because of the treatment of the complexities of the aftermath of the war, but because some storylines were over-extended whilst others were dealt with rather brusquely, and, most of all, the frequent use of sequences where one of the characters not only ‘sees’ someone who is dead, but has a conversation with them. Very tiresome. But a small gripe in the scheme of things. I’m not a historian but I have read a great deal about the Occupation of France and found no inaccuracies – even where an incident seemed initially improbable, on investigation it proved to have been very accurately portrayed.

The Miss Marple Mysteries

BBC4 very kindly reshowed all the Joan Hickson Marples, and I thoroughly enjoyed them all. She is the definitive Miss Marple, those eyes are piercing rather than twinkly and when one character describes her as ‘a cobra in a twin set’ you know exactly what he means. When she has the perp in her sights she deals with them with cold contempt, and anger on behalf of the victims of the crime. I always found Poirot a bit irritating, but Hickson’s Marples are very satisfying classic mysteries.

Mix Tape

An absolute delight. The bits filmed in Sheffield were a lot of fun, and the idea of a romance told through songs recorded on a cassette tape is poignant and charming. Excellent script and performances. I read the book and was very interested to see the changes to the plot – I can’t say any more without spoilers for both TV series and book…

Outrageous

The Mitford sisters are endlessly fascinating. This is based on the collective biography by Mary Lowell, which, to my mind, goes rather gently on the fascism, perhaps wanting to balance it out with Jessica M’s hardline communism. The TV series only gets us to 1936 so I hope there will be another series at least to take us through the war years and beyond, and I will have to see in that case how that moral balancing act is handled once we get to the nub of what Nazism and Stalinism are about.

Paradise

Absolutely superb. Sterling K Brown is totally compelling in the lead, and the plot manages to twist and turn without sacrificing the integrity of narrative or character. I’m saying nothing more – it’s brilliant and I would highly recommend it to anyone who likes a good thriller.

Prisoner 951

This dramatisation of the events following Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s abduction as she tried to return to the UK after visiting family in Iran is compelling and maddening. It certainly didn’t leave me with any positive impressions of the FO or the succession of Foreign Secretaries who assured Richard Ratcliffe that they were doing everything they possibly could, whilst being unable to identify anything they actually had done. I had no positive views of Boris Johnson anyway, and his remark that Nazanin was in Iran ‘training journalists’ was a bit of typical Johnson carelessness – he must have known that she was there on holiday to see her parents and that this entirely incorrect statement could be used against her (as it was).

The Ridge

A NZ/British murder mystery which doesn’t go where one expects it to go, so it keeps the viewer on their toes. Lauren Lyle (seen recently as Karen Pirie) is a brilliant protagonist – there’s not a great deal I can say without risking spoiling things for you, but it was a cracker.

Scrublands: Silver

I haven’t seen the first series, but from the allusions made in this, it seems that Mandalay, the rather gloriously named partner of the journalist hero, has an unfortunate knack to find herself in the midst of bloody mayhem. This is well written, and it was a compelling drama, albeit with the occasional well-worn crime fiction trope popping up.

The Serpent Queen

Dialogue totally contemporary – fine by me, those prithees can get a bit tiresome, but it walks a fine line, if the dialogue suggests ideas/attitudes that would not have occurred or been understood in 16th century France/Italy. I think it gets away with it, as it does with the asides to camera, allowing Catherine de Medici to commentate on the action. She’s a fascinating figure, historically and as portrayed here – by Liv Hill as a young woman and then by the always magnificent and compelling Samantha Morton in later life. It’s been compared to The Great (another Catherine, this time the Russian Empress), but I never saw that so can’t judge whether this is, in comparison, not Great but just good, as some reviews suggested. I am enjoying it – I don’t know this period of French history well, but have encountered bits of it in various historical novels that I devoured as a teenager and more recently in Dumas’ La Reine Margot and the brilliant Patrice Chereau film of that book.

Shooting the Past/Perfect Strangers

BBC4 has been re-showing some of the best TV dramas from the archives, and these two from Stephen Poliakoff were fascinating. I’ve linked them not just because the writer (and some cast members) are in common but because of the theme of photography and memory which is central to both. Beautiful writing, superb performances.

Smoke

Lord, this is dark. I thought I knew what I was in for, but then it took a rather violent swerve and nothing was as I’d expected. Grim and dark and, whilst very well done, requiring a certain robustness of mood to be able to deal with it all.

Stranger Things

The last ever series, and I both don’t want it to end and feel that it’s right that it should. At the time of writing, I will still have the Christmas Day batch of episodes and the final final episode to watch, so I may add a note to next year’s first screen review blog about how they brought the series to a close, but meantime, it is as brilliant as ever, intense, genuinely scary, funny and clever. I cannot understand why M and I didn’t watch it, since our shared love of Buffy and of Stephen King’s opus makes it so very much our kind of thing. But we didn’t, and so I have watched it on my own, constantly wanting to turn to him and comment on some aspect of the plot. I’ve loved every minute of it, anyway.

Trespasses