John Hallett, 26 December 1927 – 30 March 2025

Trying to sum up anyone’s 97 years of life in a not unreadably long blog post is a challenge. In the case of my Dad, John Hallett, who died on 30 March, it’s impossible. As a friend put it, at the celebration we held for his life, he packed at least two lifetimes into those 97 years. And each time I talk or write about him, someone reminds me of some other project, activity or passion that I’d forgotten, or never even known about. He set the bar very high for us all – whatever I’ve achieved in my life seems small beer in comparison – and he wasn’t always very good at telling us how proud he was of us (this was a generational thing, and certainly learned from his parents), though we know he said it to others. My niece had the poignant experience of hearing her grandad, who no longer recognised her, telling her about his lovely granddaughter and great-grandson and how proud he was of them. Most importantly, we knew, always, that we were loved, and that our parents’ love was not conditional upon us achieving things, and that gave us the freedom to be who we wanted to be, who we were meant to be.

John’s early life was pretty conventional – his father was a civil servant who’d fought in the first war, and was an active member of the Home Guard in the second. They lived in Thornton Heath, where Dad was born in 1927, and then moved to North Harrow with his two younger siblings. As a young teenager during the War, he enjoyed the excitement of spotting aircraft and watching the searchlights to cheer as German planes were shot down, until one of his schoolfriends was killed along with their family during the Blitz – a sobering experience. This did not, however, dampen his enthusiasm for aircraft, and the first stage of his career was in aircraft design.

John took up an apprenticeship at de Havillands, leaving school against the wishes of his father, who had wanted his eldest son to follow him into a stable career in the civil service, and he stayed there for four years after the apprenticeship, working in the Design Office.

He left de Havillands because, as a Christian pacifist, he could not countenance working on military projects, and he had begun to think of a future as a teacher, inspired by people he knew and admired. He trained at Westminster College, and then took up his first teaching post at Chatham Technical College (teaching technical drawing, maths, and RE). By then he was married to Cecily, who was to be his strength and his stay until her death in 1995. They’d known each other for a long time, through church, but only gradually came to realise that their friendship was blossoming into love. They lived at 24 Blaker Avenue, in Rochester, Kent. I was born in a Chatham hospital in 1957, Aidan and Claire were born at home in 1958 and 1960 respectively.

The faith that he and Cecily shared was fundamental to their lives, and whilst I do not share their faith, I do share so many of their values, their political beliefs and their approach to what is important about life. They were pacifists, members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation. They were passionately anti-apartheid (many of their ‘expatriate’ colleagues in West Africa at least considered moving on to South Africa or Rhodesia when Nigeria imploded into civil war, but that idea was anathema to them). I learned from a very early age about the slave trade, visiting forts along the Ghanaian coast where slaves had been held before being transported across the Atlantic, and was aware of civil rights struggles in the US and anti-apartheid activism in South Africa and Rhodesia – political issues of the day were a staple of discussion around the dining table each evening. They were socialists, staunch Labour voters. And they were concerned about the environment long before it was the norm.

They both became interested in the idea of working in West Africa, in one of the newly independent nations, but realised that John would need a University degree to teach there. So he did A levels at a local technical college and then enrolled at City University in London, on a scheme designed for those who had been unable to study to degree level during the war years, and obtained a First in Physics and Maths. John was studying part-time alongside his teaching post, whilst Cecily managed the home in Rochester, and brought up the children. John’s father Dennis, a deeply conservative man, never came to terms with the plan to work in West Africa (or ‘darkest Africa’, as he consistently called it), and when we returned home on leave, John had to wait until his father had left the room before talking to his mother about our experiences there.

The family flew out to Ghana in 1960 (with three children, of whom I am the eldest, then aged 3), and a new home on Asuogya Road, on the campus of Kwame Nkrumah University of Science & Technology in Kumasi. Their fourth child, Greg, was born in Kumasi in 1962. John hadn’t had a conventional route to University teaching, and used to comment that he’d arrived as a lecturer having never attended University before – he also often felt that he was only one lecture ahead of his students.

Both John and Cecily became involved in the life of the University, particularly in chamber music concerts. Cecily was an accomplished pianist, and Arthur Humphrey, a colleague, friend and honorary grandparent, played the spinet and recorders. They also held more informal musical evenings, which John’s colleagues and students from the University regularly attended. John preached regularly (both he and Cecily were Methodist lay preachers) at small village churches outside Kumasi, one of which presented (and robed) him in a splendid kente cloth on his last visit. We still have the cloth, somewhat faded and a little damaged after all these years, but still a beautiful reminder of the life we had in Ghana.

He taught Physics and Maths at KNUST but became increasingly interested in pedagogy, rather than in the research aspect of his subjects (despite pressure from his Head of Department – he resisted the idea of, as he put it, knowing more and more about less and less), and was an examiner for the West African Exam Council, and Chief Examiner for O level (the latter involved him designing practical tests which could be carried out in any school, and visiting schools to assess whether they had the necessary apparatus). He was involved with the Ghana Association of Science Teachers, and wrote a Physics O level textbook tailored to the resources available in West African schools and to the experiences of the students, which remained in print for many years.

This growing interest in education per se led him to take up a post at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Northern Nigeria and the family moved there in January 1966. I don’t recall the first part of our journey (by sea from Tema to Lagos) but vividly remember the 600 mile train ride from Lagos to Zaria. The timing of our move turned out to be most inauspicious, as a series of coups and counter-coups rocked the region, and massacres of Igbo people took place in May and September of that year in the area where we lived. We were not in danger at this stage – the violence was very precisely targeted at Igbo people – but of course it was traumatic for the adults to witness what was happening, often to people they knew, and they kept as much of this from us as possible.

The only incident that I recall was when a group of men approached our house, and Cecily and a neighbour took all of the children upstairs and put a record of children’s songs on, whilst John and the neighbour’s husband went outside to speak to them. Strangely, in my memory the men were carrying sticks, but in reality, as I discovered much later, they had machetes. They turned away from our house, but went on to kill a number of people nearby.

I remember being aware of conversations between the adults that stopped abruptly when they realised I was within earshot, but it was not until my teenage years when I pieced together the fragments to understand what had been happening, and this was formative. There is one particularly powerful story that I discovered from talking to my parents and visitors who had been in Nigeria with us. Opposite our house was an unoccupied bungalow, in which we used to play sometimes. I recall being forbidden to do so – snakes were mentioned and I needed no other deterrent. In reality, John had discovered a couple of young Igbo men hiding there. He got them into the family car, covered in blankets, and drove them to the army base, where it was hoped they would be safe. Meanwhile a friend who worked for the railways commandeered a train to take Igbo refugees south to safety, and these two young men joined that group. Tragically, the train was deliberately derailed, and they and others who were fleeing the pogroms were murdered. On both of these occasions, John felt that he had to at least try to intervene. I have often wondered how he felt as he approached the armed men outside our house, and how Cecily felt, knowing what he was doing. And how he felt as he drove those young men to what he hoped might be sanctuary, knowing that if the car was stopped and searched, they would be killed, and he might be in danger too. I don’t know, because he never spoke of these events in personal terms. I believe he felt that he had no choice but to act as he did, whatever the risk.

As I learned about these events, which had happened around me, without my knowledge or understanding, I found I needed to understand the wider issues, and this lead me to read widely about Partition, the Holocaust and the Rwandan genocide.

The family returned home on leave in the summer of 1967, but the worsening situation meant that Cecily and the children could not return, and John travelled back to Zaria alone, to complete his contract, returning to the UK in Easter 1968. We did visit him at Christmas, a rather nervy visit given the volatility of the situation and the presence of armed (but barely trained) soldiers around the city.

Someone once asked me if I blamed my parents for taking us to West Africa, a question that utterly baffled me. On the contrary, I’m in awe of their courage in taking that step, and very grateful for it too. We gained so much – on our return to the UK our horizons were so much wider than those of our contemporaries, and whilst that meant we had a lot of catching up to do on popular culture and so on, it gave us a different perspective, and I think a more generous one. Certainly those years – and the culture of talking about politics and ethics and religion in our home – informed each of us in our developing views about all of those things as we grew older. We would not be the people we are, had our childhood been spent in England.

Cecily and the children were living in the family house in Rochester, and places were found for us at the local primary schools, but on John’s return he took up a post in the Education department at Trent Polytechnic, where he would remain until his retirement. He and I found a temporary home with one of his old friends (a fellow member of the ‘Brew Club’ at Westminster College), so that he could start at Trent, and I could start at Queen Elizabeth’s Girls’ Grammar School in Mansfield. The rest of the family moved up to Nottinghamshire once our new home in Ravenshead was completed.

Whilst at Trent, John was involved in innovative initiatives such as the generalist Education degree and the Anglesey project, worked with VSO to train volunteers for their overseas service, and also took up every opportunity to travel with the British Council or under the auspices of the Polytechnic to visit schools and educational projects in Nepal, Kenya, and the USA. In addition, John was very concerned with the environment, and published, with Brian Harvey, an economist, a well-received textbook on Environment and Society in 1977.

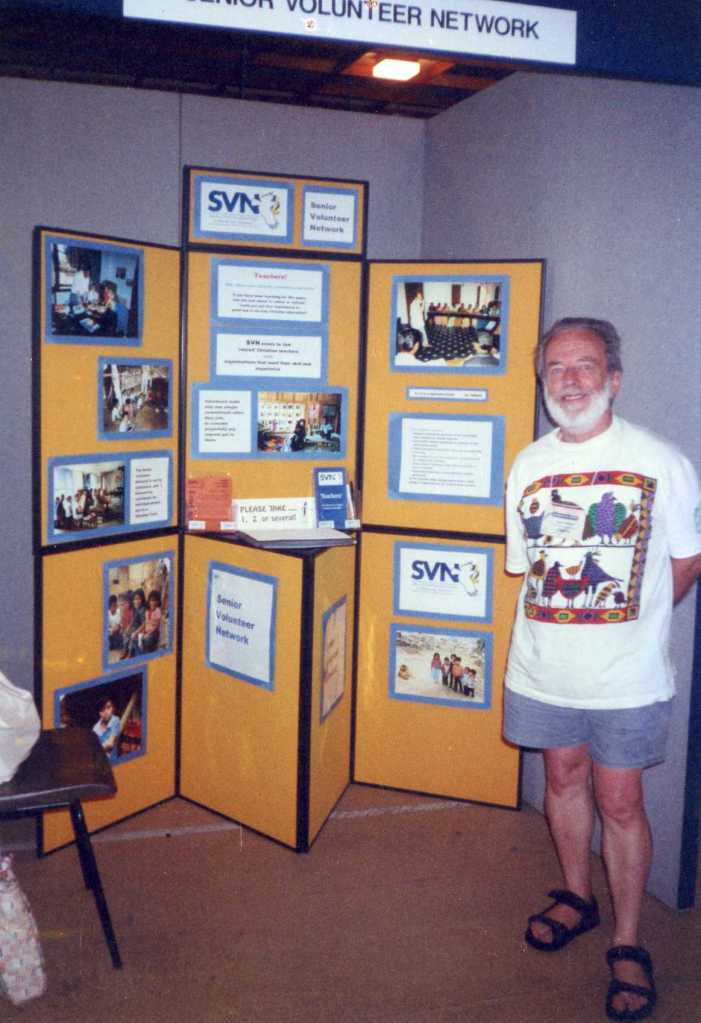

He retired (by then he was Head of the Education Department) in 1987, aged 60, but rather than leading a quieter life, he had a vision for a charity, Senior Volunteer Network, which would put retired teachers/head teachers and other education specialists into projects worldwide, and began to turn this into a reality.

He and Cecily made the most of the freedoms of his retirement (she had retired from primary school teaching some years previously). They both became involved in leadership of the Ravenshead Christian fellowship, which later became Ashwood Church (now based in Kirkby in Ashfield). In the early days of the Fellowship, we met in members’ homes or in the Village Hall. John and Cecily held open house on Sunday afternoons for young people in the village (50 years on, people still talk about how the house was full, every seat taken, and every window ledge and the stairs too) – their home in Ravenshead was called Akwaaba, which in the Twi language spoken in the part of Ghana where we had lived, means ‘welcome’. Part of our parents’ joint legacy to us is the idea of family as an open, welcoming place that embraces new members, whether related by blood, law or none of the above. In West Africa we were a long way from our aunts, uncles and grandparents, and so we accumulated a number of aunts and uncles, friends of my parents who visited regularly, and who I still think of as ‘Aunty Betty’ (with whom I still exchange Christmas cards), ‘Uncle Arthur’, or ‘Uncle Rex’. And in Ravenshead that took the form of opening our doors to random teenagers, some of whom became part of the church (and still are), others who never did, but had reason to be grateful for our parents’ warmth and support, as well as for the Sunday afternoon tea.

As keen walkers, John and Cecily led youth hostelling expeditions to the Lake District, one of which memorably involved Cecily’s group of walkers requiring the Mountain Rescue Service, after getting lost on Great Gable in driving rain and mist. John’s group had taken what was expected to be the more challenging route, only to find when they got to the hostel that we had not yet arrived. They called at the Mountain Rescue centre, at roughly the time that two of Cecily’s party arrived, having been sent out as envoys whilst we huddled behind a rock for (minimal) shelter, and gave their account to the team, enabling them to find their way straight to us.

John was a governor at a number of local schools, volunteered with Mansfield Samaritans (Cecily was a founder member of this branch), and was involved in local politics. He ran regularly, and completed the London Marathon, aged 63, in 1990 – he’d been a keen runner as a young man (plenty of stamina, less speed, due to his short stature), which had taken its toll on his knees and he had to have two knee replacements later in life. He undertook many walks with Cecily (and their dog, Corrie) after his retirement, including the Coast to Coast Walk, and along the Northumbrian coast. Having visited Nepal during his work with Trent Polytechnic, he returned to Everest to climb as far as the snow line, fulfilling his dream to stand on its slopes.

In 1995 Cecily died of pancreatic cancer, aged 65, only a matter of weeks after the diagnosis. It was a huge shock, and an incalculable loss to John and to the family – and to so many more people, as we all discovered from the messages that flooded in after her death. She saw herself as an accompanist – in musical terms this means that she wasn’t there to do the virtuoso solo stuff, but to enhance the performance of other musicians – but she did far more than that, and could have done so much more (at the time of her death she was gaining qualifications in counselling, and working with a Nottingham homeless charity). At the events celebrating Dad’s life, so many people talked not just about John but about ‘John and Cec’. They had different, and complementary strengths, they were a partnership in every sense, and their legacy is a shared one, for us and for the many other people with whom they worked and worshipped.

When Cecily died, SVN was still an idea rather than a reality, and in the aftermath he threw himself into setting up and leading the network, sending volunteers around the world, and travelling himself until his eyesight began to fail due to macular degeneration. SVN still thrives, and the family still has links with it, through Claire who is now a trustee.

John remained active until his 90s, undertaking a skydive to celebrate his 90th birthday, but his sight loss was by then significantly restricting his activities as he could no longer drive, or use the computer. The pandemic shrank his horizons significantly, particularly since he could not easily compensate for the loss of face-to-face social activity with on-line due to his deteriorating sight. In 2020, just before the first lockdown, his youngest son Greg died of bowel cancer, a desperately heavy blow. The death of my husband Martyn in 2021 was also a major shock to him. In 2022 he was formally diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and the decline from that point on was fairly rapid. He was cared for at home by Claire until he needed residential care, and moved into Lound Hall Care Home, near Retford, in 2023.

During those last years, as the fog engulfed him and he became more dependent on others, it was sometimes hard to remember the man he had been. He was a man of bold decisions – leaving school to work at de Havillands, against his father’s wishes, leaving de Havillands on a matter of principle, training as a teacher and undertaking a part-time degree whilst working, taking his young family to West Africa (again, a decision of which his father profoundly disapproved), and then changing direction again to focus on education, and finally setting up SVN in his retirement and travelling to often remote and dangerous places to work on educational projects. He was a leader, from his days as a Cub and Scout where he progressed from ‘Sixer’ to Assistant Scout Master, to his final post as Head of the Education Department at Trent and his role in the church. We all remember family walking holidays when Dad would lead the way so confidently that we all had to rush to keep up, as he was the one with the maps and the refreshments… At the care home, he often, when we visited in the early days, told us that he was there to conduct a review or an investigation, or that we were all at a conference that he had organised. That lifetime of leadership kept a hold even when so much else had been lost.

He had, from a young age, a sense of purpose, and one of his frustrations as his eyesight began to fail was that so many projects – travel abroad, or even ambitious UK walks like the ones that he and Cecily had done years before – were no longer practical or safe. For a while, writing his memoirs became his purpose, although in the final stages of the project dementia had begun to rob him not only of his memories but of understanding, and so I edited the document and arranged publication so that a copy could be placed into his hands whilst he could still recognise it as The Book, his own work.

John was fascinated by the natural world, greatly enjoying finding out about the flora and fauna – particularly the birds – of the parts of West Africa where we lived, and David Attenborough’s documentaries were a source of pleasure and interest in his last years. He read widely, and not only for professional purposes, and turned to audio-books after his sight loss, through which he enjoyed re-‘reading’ Dickens, Trollope, le Carré, Graham Greene and others, as well as discovering new writers (he was particularly enthralled by The Book Thief). He greatly admired the work of C P Snow, a scientist as well as a writer, who explored the idea of the two cultures, science and the arts (Snow’s novels were sadly not available in audio form). He loved music – as a young man he listened to jazz (New Orleans, and Django Reinhardt, not swing, as he told me firmly), but then was converted wholeheartedly to classical music after hearing Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos. Even in the very last stages of his illness he seemed to find calm in listening to Bach and Mozart in particular.

Just over a year ago, I wrote about Dad’s dementia, and specifically about Dad’s ‘raging against the loss of dignity, the loss of control over where he is and what happens to him, against the loss – even if he can no longer articulate it – of the things that made him him, against the slow dying of the light.’ And I expressed our heartfelt wish that his last days should not be spent ‘burning and raving at close of day’. In the end, at the very end, he did ‘go gentle into that good night’, with staff from his wonderful care home taking turns to sit through the night with him. We’re grateful for that, and that we each had the chance to say goodbye, to kiss him on his forehead and tell him that we loved him.

John is survived by his children Catherine, Aidan and Claire (youngest son Greg died of cancer in 2020), daughters-in-law Julie and Ruth, grandchildren Matthew, Arthur, Jordan, Melanie, Vivien and Dominic, step-grandson Tom, and great-grandchildren Jackson, Jesse and Eliza. He will be remembered with love by all of us.

#1 by dowlies on June 16, 2025 - 9:02 pm

A beautiful account of a wonderful life, well lived. It was a pleasure and privilege to have known John, whose principles, faith and experiences are truly inspiring.

LikeLike