I’ve been trying to build BlueSky as a place to focus my social media if/when X/Twitter becomes too toxic or melts down altogether. So when BookSky featured a challenge to post covers of 20 books that had had a major impact/influence on me, I jumped at it, thinking (rightly) that I might well find amongst the others joining the challenge or responding to my choices people who were worth following, and followed it up with 20 records, and 20 films. (I really, really like lists). The books that I chose are all ones that I’ve talked about on this blog at various times, as are the 20 albums. But I’ve never blogged about my top films. And the BlueSky thing specified no reviews, no details, just the book cover, CD/LP cover or film poster, so here I have a chance to tell everyone not only which 20 films I chose, but why.

This isn’t my stab at picking the 20 best films ever. I could make a case for some of them, but not all. It’s about their impact on me, and that’s subjective, whatever their critical and/or popular standing. I ruled out films where I could not readily recall that first viewing, the when and where of it, but more importantly the feeling of it. Some of these films packed a huge emotional punch, left me wrung out and still sobbing after the credits had rolled. (A lot of these films made me cry – as anyone who has watched a film with me will know, that’s a very low bar – but that isn’t a criterion in itself.) Some of them immediately intrigued me, made me want to watch them again (and again) to figure them out, to understand some of the layers of meaning. In some of them (and these aren’t mutually exclusive categories) the look or the sound of the film (not necessarily the music) were a huge part of their power. But all of these films stayed with me from that first viewing, not only as I made my way home from the cinema, or off to the kitchen to get a cup of tea, but long after. And all but the most recent have proved that they sustain their power on subsequent rewatches.

Of course, making any such list, as those who are addicted to list-making know, is about what you leave out as well as what you include. To get it to 20 meant rejecting films that I love, and that felt bad. I could easily pick another 20 wonderful films, but they wouldn’t quite meet my stringent self-imposed criteria. So these (in no particular order) are the ones that survived the cull, and I’ll tell you why.

Arrival (2016, dir. Denis Villeneuve)

A pretty much perfect film. It has everything one might want from a ‘first contact’ sci-fi movie but then more, much more, than one might expect. The search for a way of communicating is clever and thought-provoking, but also very moving (it reminded me of my favourite Star Trek: Next Gen episode, ‘Darmok’). And the final part of the film – I can’t say anything too specific because if you haven’t seen it, then you need to, and whilst it stands up to any number of rewatchings, the moment on a first watching when one grasps what it is that has happened is so powerful that it should not be compromised. It’s all visually stunning too. The score is one of Johann Johannson’s best, and that’s saying a lot. It’s worth reading too the short story on which the film is based, Ted Chiang’s ‘The Story of Your Life’.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1946, dir. Frank Capra); Music – Dimitri Tiomkin

I resisted this for years. I’d seen it described as ‘heartwarming’, which is a red flag for me – I don’t mind my heart being warmed, but I resent a film/book explicitly setting out to warm it. But when I eventually succumbed and watched it, I found that whilst the very final scene did, indeed, warm my heart, that sentimentality had been more than earned. Capra’s hero is a good man, without any doubt, but we see him tormented by regrets, and by resentment that doing the right thing, as he must, ties him down and traps him in domesticity and small-town life, when he longed and longs to travel the world. He’s angry, and that anger shows. He’s a good man, but not a saint. And so we can identify with his frustration, his regret, even the anger. I always watch this film a few days before Christmas – that became a tradition as soon as I’d watched it that first time – and each time I weep at the opening sequence, as the prayers for George go up to the heavens, and keep weeping, off and on, until The End. There are odd moments at which I wince every time (I hate the way they all patronise Annie, most particularly, and I’m not entirely reconciled to Mary’s transformation into a scared of her own shadow spinster in Pottersville, though there are ways of interpreting this). It’s not a perfect film, in other words, but it’s a powerful and profound one, that goes to very dark places but shows the way out of them. See, if you’re interested, my two previous blog posts about IAWL: You are now in Bedford Falls | Passing Time, Letting it get to you: Doctor Who and George Bailey | Passing Time

Le Mepris (196 , Jean-Luc Godard); Music – Georges Delarue

I don’t tend to love Godard – give me Resnais (see below), Truffaut or Malle any day if we’re talking Nouvelle Vague. But while I was doing a part-time French Language & Cultures degree, which had a very strong cinematic bent, we had a module on intertextuality and studied this particular film in depth. It’s absolutely rammed with intertextual references – the very presence of Fritz Lang, the film posters in the scenes at Cinecento, the books that the characters read, the Odyssey… My enjoyment of the film is more purely intellectual than for most of the films in this list, but no less powerful for that. One can analyse – and we did – every shot, for its use of colour, its framing, its intertextual details, but also the plot, which has layers of ambiguity that keep one pondering. It’s visually very striking, and that strange house – the Casa Malaparte on Capri island – is quite disturbing (I had a strong sense of vertigo when I watched the film on the big screen).

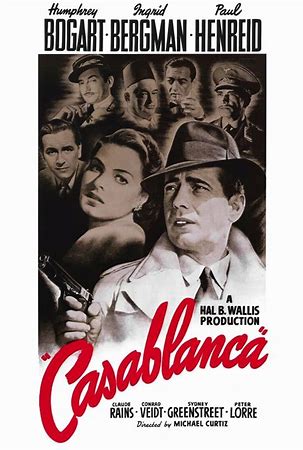

Casablanca (1942, Michael Curtiz); Music – Max Steiner

I loved Casablanca from the first time I saw it (how could one not?). Bogart, Rains and Bergman. The Marseillaise scene. The dialogue, crackling with dry wit. And somehow, that film gets richer and stronger every time I watch it. When I first realised just how many of the people involved in the film – both behind and in front of the camera – were refugees from Nazi Europe, that brought a depth to many of the scenes that I hadn’t realised on first watching. It’s not just the big names (Conrad Veidt, Peter Lorre, Paul Henreid), or the second-tier cast (e.g. Curt Bois, Madeleine Lebeau, S Z Sokall) – the couple earnestly practising their English for their hoped-for new life in the USA, Frau and Herr Leuchtag, were both played by Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany/Austria (Ilka Gruning and Ludwig Stossel). One can love the film without knowing any of this – it’s a pretty much perfect film however one looks at it. The Marseillaise scene always reduced me to sobs, but knowing that Madeleine Lebeau, who plays Yvonne, had had to flee Paris ahead of the Nazis, and that her tears (and those of many of the other cast and crew in that scene) were real and heartfelt, makes it utterly compelling. The film Curtiz provides fascinating background to the director and the production of Casablanca and is well worth seeing.

Last Year at Marienbad (Alain Resnais); Music – Francis Seyrig

I wrote a whole blog about this film. So I won’t repeat myself, other than to say that Alain Resnais is probably my favourite Nouvelle Vague film director, and that one of the things I like about him as that whilst the films he made in the 50s and 60s were enigmatic, heavily intertextual, non-linear, intellectual, he went on to make more comedies, including a number of films of Alan Ayckbourn plays (e.g. Coeurs (Private Fears in Public Places) and Smoking/No Smoking (Intimate Exchanges), much more accessible but still clever and thoughtful. In Marienbad, one of the quintessential new wave movies, there’s a moment when one can see, briefly, the unmistakable silhouette of Alfred Hitchcock (I didn’t believe that when I read about it, but it’s there, I promise – what it tells us is another question). And Resnais, apparently, was a big fan of Marvel, and wanted to work with Stan Lee. Again, I’m not joking. And that leads us neatly on to…

The Avengers (2012, Joss Whedon); Music – Alan Silvestri

The first in a stunning sequence of superhero movies that came to a powerful climax with Endgame. This one has everything that one might wish for from a superhero movie – massive battles, superb CGI, gorgeous superheroes, and a clever, witty script. That final element is courtesy of Joss Whedon, who – though we did not know it then – is highly problematic. But at the time this was released, I was a huge fan primarily because of Buffy, and his script here brings not just humour but depth to the story. Whedon didn’t continue to play much of a part in the Marvel glory years, but he set the tone. I had no background with the comics (graphic novels, whatever), so came to these characters fresh and fell for them. I wrote a blog about Marvel too…

West Side Story (1961, Robert Wise); Music – Leonard Bernstein

I love the Spielberg version – it seems to me that it honours the original without being afraid to change things about it. But for the purposes of this list, it is the original movie that I’m going back to, because the impact of that, on first and on every subsequent viewing, was so great. The choreography is mesmerising, the songs are glorious, the ending is so powerful – that moment when Tony’s guys try to lift his body, and stumble a little, and the others come to take his weight. I can write about it but I can’t talk about it without choking up. It is the finest musical ever (I’m aware that other fine musicals are available, but this just tops everything else).

Girlhood (2014, Celine Sciamma); Music – Para One

Celine Sciamma is probably my favourite current French film director. This is the first film of hers that I saw, and it is gripping, moving, powerful, from the opening sequence. The Roger Ebert site reviewer says: ‘There are many moments that linger in the mind long after the film has ended. The epic slo-mo all-female football game of the opening. An early scene showing a raucous group of girls heading back to the projects, all talking at once, until they fall into silence, collectively, when they approach a group of boys lounging on the steps…’. And I would add the scene where the group of girls try on shoplifted dresses, in a motel room, miming to Rihanna’s ‘Diamonds’… The film is desperately sad, but there’s beauty here too, and humour, and just a smidge of hope. A tough watch but eminently worth it – and I also love Petite Maman and Portrait of a Lady on Fire.

ET (1982, Steven Spielberg); Music – John Williams

Possibly Spielberg’s best. It has his trademarks – the child’s viewpoint, mirrored by an adult who hasn’t forgotten, the sense of wonder, the humour and the sense of loss. I cried through much of this when we first saw it in the cinema (I was not alone in that, as became evident when the lights went up), and cried so much when I first tried to watch it with the children that I thoroughly put them off the film for quite some time. But there’s so much joy in this film – I love the scene where ET gets tipsy at the house, and Elliott picks up his inebriation telepathically, and most of all the moment when the bikes take flight… Having watched The Fabelmans one does tend to read back into Spielberg’s movies from his own childhood, but I don’t think one needs to here – anyone can, whatever their age, if they let themselves, identify with Elliott.

Hidden/Caché (2005, Michael Haneke)

This one has an opening scene which is guaranteed to make cinema audiences start restlessly muttering about whether to alert the cinema staff that something has gone wrong, and home audiences double checking whether their TV or DVD player has frozen. M always quoted this one as the epitome of French film – in his view, a film in which nothing happens, at great length, and with a lot of talking. Which is fair, TBH, but I love it. When things do happen, they hit you with great force, and certain scenes have stayed with me through the years since I saw this at the cinema. It also sparked an interest in a largely forgotten (rather, deliberately hidden) historical event – the massacre of Algerian demonstrators in Paris in 1961. I had never heard of this when it was referred to in the film and found it hard to believe that this could have happened and yet be almost completely unknown. De Gaulle’s censorship was astonishingly effective even outside France and its territories – I discovered when talking to my father that he had heard about the event, but from the newspapers in Ghana where we were living in ’61. I noticed looking at the film’s Wikipedia and IMDB entries that no one is credited with the music – I hadn’t registered the lack of a soundtrack (other than in that opening scene) but it’s intriguing that Haneke chose not to use one. When I next rewatch the film I will be aware of that.

Little Women (2019, Greta Gerwig); Music – Alexandre Desplat

It has to be the Greta Gerwig version. I grew up with the book, identified fiercely with Jo, wept over Beth, and followed them all through to Jo’s Boys and Little Men. I’ve seen various adaptations, on film and TV, over the years, most of which have had something to recommend them, though I recently re-watched the Winona Ryder version and was cross about how girly Jo got about the Prof. But I saw the Gerwig film in very early 2020 and it was a deeply emotional experience. It took me back to the book by deconstructing the book’s chronology and leaned fully into the trope of Jo being both the author and the subject and the two not being identical. But more than that – in early 2020 I knew that very soon I would be losing my little brother, who had been diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2018, and whose journey was very close to the end. So those scenes with Jo and Beth broke me and do so still. It’s another film that I watch every Christmas – even though this version doesn’t open with Christmas – and at the same time that its depictions of family and the closeness of siblings is terribly sad when one has gone (we were four, until we were three, just like the March family), the glorious chaos of four siblings close in age and different in temperament, all talking across one another, squabbling and making up and holding each other close is joyful too.

Timbuktu (2014, Abderrahmane Sissako); Music – Amine Bouhafa

Having seen Sissako’s earlier film, Bamako, a remarkable and fascinating exploration of globalisation through the device of a trial taking place in the courtyard of a home in Mali’s capital, I caught this one at the cinema as soon as it came to Sheffield. It’s about the occupation of Timbuktu by extreme Islamist group Ansar Dine, who impose harsh laws (banning music, making women cover their bodies and even their hands, banning football). Set against this is the story of a small family based outside the city, making a living from their livestock. Sissako shows moments of resistance – the imam who rebukes the occupiers for entering the mosque without removing their shoes, the boys who carry on playing football after their ball is confiscated (a lovely sequence, in which it is very easy to forget that there is no ball, as they swerve and tackle and shoot). Like Bamako, the film is partly about language – we hear Arabic, French, Tamasheq, Bambara and English, and this is linked to the notion of justice as a man is tried for murder in a language he cannot understand. It’s a powerful, tough, beautiful and witty film – and it’s complex too, making the invaders human rather than merely monstrous. The Guardian reviewer said that Sissako ‘finds something more than simple outrage and horror, however understandable and necessary those reactions are. He gives us a complex depiction of the kind you don’t get on the nightly TV news, even trying to get inside the heads and hearts of the aggressors themselves. And all this has moral authority for being expressed with such grace and care. His film is a cry from the heart about bigotry, arrogance and violence.’

The Gospel according to Matthew (1964, Pier Paolo Pasolini); Music – Luis Enriquez Bacalov, inc. Gloria (Missa Luba), Bach, Odetta, Blind Willie Johnson, Kol Nidre

An Italian neo-realist take on Matthew’s version of Jesus’ story, with non-professional actors. It tells the story as Matthew presents it – full of the miraculous. Nothing is added – even the dialogue all comes from the Gospel. Pasolini was hardly the most likely prospect for such a film, given that he was a gay Marxist atheist, but as he said, ‘If I had reconstructed Christ’s history as it actually was, I would not have made a religious film, since I am not a believer. I do not think Christ was God’s son. I would have made a positivist or Marxist … However, I did not want to do that, I am not interested in profanations: that is just a fashion I loathe, it is petit bourgeois. I want to consecrate things again, because that is possible, I want to re-mythologize them.’ The end result is beautiful, strange, remarkable. The soundtrack draws on sacred/religious music from various cultures and introduced me to the Missa Luba, the ‘Gloria’ from which gave me goosebumps when I heard it in the film.

All of us Strangers (2023, Andrew Haigh); Music – Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch

The Guardian described this as ‘a raw and potent piece of storytelling that grabs you by the heart and doesn’t let go.’ I’d read reviews before watching but I wasn’t ready for the way the film handled Adam’s visits to his parents, let alone for the ending. It somehow tapped into my own sense of loss (my parents – one gone, one lost in dementia – my younger brother, my husband). I will watch it again some day to appreciate it fully, but it will be some time before I’m ready.

Last of the Mohicans (1992, Michael Mann); Music – Trevor Jones/Randy Edelman

From that opening sequence, with Day-Lewis running through the woods (‘like a force of nature’, as one reviewer put it), to the dramatic clifftop climax, it’s tense, violent, incredibly romantic and completely absorbing. I’ll be honest, DDL usually inspires more admiration than adoration from me, but here I was with Cora all the way. The film messes with Fenimore Cooper’s book, and with history, but that’s fine. It doesn’t have grand ambitions – it’s quite an old-fashioned film, but it works wonderfully.

Assault on Precinct 13 (1976, John Carpenter); Music – John Carpenter

The original. Obviously (I include an image below from the remake, which I’ve never seen, but maintain is entirely uncalled for). Absolutely gripping – the action is relentless, and one tends to forget to breathe. The ice cream van sequence is horrifying (and Carpenter apparently said that he would have toned that down if he’d made the film later) but I never felt it was gratuitous. The plot is stripped down to bare bones and all that you really feel whilst watching is that you are in that semi-abandoned police station and that you’re under attack, from an enemy who is not going to give up until either all of them or all of you are dead. Brilliantly done, and you might need a lie down afterwards.

The Best Years of our Lives (1946, William Wyler); Music – Hugo Friedhofer

I’ve seen this a number of times, but not for quite a while so it is overdue a rewatch. After all of the heroics of the war movies, here is a sober, realistic portrayal of what three ordinary men came home to. It doesn’t talk about PTSD – it’s not so much (at least not explicitly) about the impact of what they saw and did out there – it’s about who they are now, how they are not the same as when they enlisted, and how/whether those who loved them then will deal with this new reality. It also shows, with honesty, the sense of purpose and comradeship that these men are missing as they try to find their way in the places that were once most familiar to them. Most famously, Harold Russell’s portrayal of Homer, who’s returned with hooks instead of hands, conveys the hurt and the humiliation of being helpless, the fear of being pitied rather than loved.

Paddington (2014, Paul King); Music – Nick Urata

Both Paddington films are superb. Yes, they’re based on books aimed at young children, and yes, the message is appropriately reassuring – bad things happen to good people but it all comes out right in the end, because there are enough good people to thwart the bad guys. Paddington himself is childlike, in the way he experiences new things, and his assumption that the people he meets are going to be benign, until proven otherwise (Mrs ‘Arris, as portrayed by Lesley Manville, reminded me very much of Paddington). His clarity about right and wrong is childlike in its simplicity but adult in its courage. This first film includes some of the most brilliantly funny slapstick sequences, which – unlike some slapstick – never really wear out their welcome. And poignant moments, reminding us about the reality of the world we live in, where we have arguably forgotten how to treat strangers. I’ve listed the first film because that had the most immediate impact – I wasn’t expecting great things really, just a pleasant and amusing interlude, but I truly loved it. It’s a family film in the best sense of that term – it’s about family as well as being aimed at all the family.

Zone of Interest (Jonathan Glazer); Sound – Mica Levi

There could hardly be a more brutal contrast with the previous film listed. There is no comfort here, not a shred. The sounds that we hear throughout the scenes at the house are sometimes neutral (machinery, trains), sometimes not (screams, gunshots) but we know what is happening on the other side of the garden wall, so we know what those trains mean. And yet, after a while, I found that I had filtered the sounds out, as one does with traffic noise if one lives on a busy road. And that was horrifying too. I have only seen Zone once, and whilst it deserves a rewatch to see the detail that one inevitably misses in a first viewing, I am in no rush. I watched it alone, and am glad that I did, because I wasn’t capable of any kind of conversation afterwards, and whereas sometimes after a disturbing film the return to familiar domesticity is reassuring, after Zone it felt (albeit briefly) wrong. I’ve spent a lot of time considering how one can make fiction (film or literature) about the Holocaust, and indeed whether one should. I’ve concluded that it is possible, and indeed necessary, to do so, but that it is also incredibly risky – it should never, ever, be ‘poignant’ (don’t get me started on that), never (heaven help us) heartwarming. If, as in a recent TV fact-based drama, there is a positive conclusion (We Were the Lucky Ones), survival was not a ‘happy ending’ but a shout of defiance in the face of evil.

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006, Guillermo del Toro); Music – Javier Navarrete

I saw this twice at the cinema, and at least twice since on DVD. It’s visually stunning, magical, terrifying, shocking. Roger Ebert called it ‘one of the greatest of all fantasy films, even though it is anchored so firmly in the reality of war’. There are two realities on the screen here, even if the child at the centre of the narrative is the only one who sees the faun and the Pale Man. This taps into so many fantasy narratives – the child who has access to another world, adjacent to, and at times or in certain places merging with our own, whilst adults are oblivious, preoccupied with their own monsters and nightmares.

P.S. I didn’t make a rule that I could only include one film per director, but that’s how it panned out (honest). There is a preponderance, inevitably, of US and UK films, but also movies from Mali, Mexico, Italy and France. Cinema takes us across continents, and also across the centuries – from the ancient narrative of Matthew’s Gospel to contemporary urban life. It’s satisfying to see that this selection, not by design, illustrates that.