I’ve been trying to write this piece for weeks now. Hesitating because, after all, why would anyone need to read the thoughts of a white, middle-aged, middle-class English woman about something she has never experienced, and could never experience? But nonetheless this post has been buzzing around in my head for so long, and I know that the only way to stop that is to write.

And, this morning, I woke as so many did to the awful news that Chadwick Boseman, the actor best known as the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s Black Panther, has died at only 43 years old. I remembered how I felt in the cinema watching that film, how exhilarating it was to see the large screen filled with powerful, beautiful black people, in control of their destinies, white people largely irrelevant. And how I thought of what that must have felt like to people of colour, those who’ve seen movie after movie where they are absent, or peripheral, or victimised, or expendable. And those who have been waiting, whether they knew it or not, for a super hero who resembled them.

Some disclaimers. I’m not trying to prove anything here, not trying to get approval or validation. I’m talking, primarily, to other white people, about how we can learn and listen, how we can recognise and take account of our privilege, and know when to speak and when to STFU. If I get something wrong feel free to tell me (but I’m not asking you to educate me, that’s my responsibility). I’m a work in progress, still, at 63. I expect and hope that I’ll still be learning, expanding my understanding, for the rest of my life, whilst my faculties are intact at least.

So, where am I from? No, where am I really from? My upbringing was very different to that of anyone I went to school with in Chatham or Mansfield in the late 60s/early to mid 70s, very different to that of my cousins and other wider family. It shaped my response to the racial politics of the UK in that era and beyond. It influenced what I read, and what I watched.

When I was three years old, we (my parents, myself and my two younger siblings) flew to a new life in Ghana, West Africa. Of course we were massively privileged in our lives there, in the immediate aftermath of independence, living on the University campus in Kumasi, where my father taught Physics and Maths. We were ‘expats’, not immigrants. No one expected us to integrate, to assimilate, to adopt Ghanaian dress or diet, or to learn the language. My school teachers were all British, my classmates included Ghanaian children, but also British, American, Canadian. (When we moved to Northern Nigeria, there were no African children in my class. Not one.)

That upbringing did not give me a means to understand what it is to be black in Britain. My white skin gave me privilege as a member of an ethnic minority in West Africa as it does here where it makes me part of the norm. But those childhood experiences did broaden my horizons, expand my consciousness and my sympathies, and gave me a wealth of experiences against which to measure the attitudes and assumptions I encountered back home.

I think first of all, of the Door of No Return. Cape Coast and Elmina Castles, two of the forts on the Ghanaian coast which were the point of departure for the slaves, the last place they saw before they were crammed into the holds of the ships for the Atlantic crossing. I don’t recall in detail what my parents told me about their history when we visited, but I still recall the place, and the association with horror, the chill, even in the humid heat of Ghana.

I remember the first time I heard a white person say something casually racist. I remember not so much shock or offence, but bafflement. It seemed to me so incomprehensibly stupid, to generalise in that way. It made no sense to me then, that first time, in Africa, any more than it did later, in Chatham or Mansfield. I never knew how to respond – where do you begin, with something so incomprehensibly stupid?

My memories of Ghana are vivid, warm, happy. I know I can lay no claim to Ghana as part of my heritage – I lived there for just five – albeit formative – years. When I use my Ashanti day name, Abena (girl born on a Tuesday) as part of my Facebook name, when I use an image of kente cloth as the background to my Twitter profile, am I, as I hope and intend, honouring a part of my life for which I am immensely and profoundly grateful, or am I appropriating something to which I have no right? But those things (and my support for the Ghana national football team, and my love of West African music) feel like part of me.

Our parents taught us well. At an early age (before we came home to England, so before I was ten years old) I knew that whilst other ‘expats’ were planning, in light of the rapidly deteriorating situation in Nigeria, to move to jobs in Rhodesia or South Africa, my parents never would. And they taught me why. (Their passionate opposition to those regimes would probably have made them persona non grata anyway.)

I knew that Martin Luther King was an important man, a good man, who represented the values that my parents were teaching us, and they had taught me well enough that I knew by the time I was ten years old that his murder was a terrible thing, a huge loss to the world.

As a teenager, I was drawn to the American civil rights struggles, and I read everything I could get hold of. I read MLK, Angela Davis, George Jackson, James Baldwin, Malcolm X.

But one of the most powerful books for me was by a white man. John Howard Griffin, a white journalist, disguised his skin with a combination of medication (anti-vitiligo treatment), tanning and cosmetics, and went South. He was motivated by the recognition that the only way to know what it was like to be black in the USA, was to become black in the USA. Of course it wasn’t the same – he had an exit strategy (although he was subjected to threats and a near-fatal attack when the book was published and his identity revealed), and he had experienced most of his life up to the point of his self-transformation as a white man with all the privileges that entails. But his account is viscerally compelling. What stayed with me from my first reading was the ‘hate stare’ – something I would never experience, almost certainly never witness.

Alex Haley’s Roots (whether it is fiction or history, or a blending of the two) gave me a black epic, a story that spanned centuries and continents, that took up the story of the people who had been herded through the Door of No Return, and did not flinch from the brutality of slavery and of the injustice that persisted for so long after.

I almost never talked about my interest in the politics of race, not to my schoolfriends. I feared discovering that their response would make friendship problematic, or impossible. And, to be honest, as a teenager desperate to fit in, I feared being regarded as nerdy or odd. We talked about pop music, telly and boys, not about politics. And the strange culture of the times meant that one tribe listened to virtually no black music (though they allowed a free pass to Hendrix), whilst another listened to mainly African-American and Caribbean music, whilst being associated with prejudice against people of South Asian origin, and with the nascent National Front. It was dangerous territory, even though in my grammar school there was, throughout my years there, just one non-white girl (from India, as I recall), and in the Mansfield area at the time, the largest immigrant community was Polish. I kept reading though, just didn’t talk about it.

I read a number of the Heinemann African Writers series from my parents’ bookshelves (Chinua Achebe, Buchi Emecheta, Bessie Head, Ngugi wa Thiongo, Camara Laye, Wole Soyinka). I read Alan Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country, and Trevor Hudleston’s Naught for your Comfort. I read E R Braithwaite’s Please Sir (a whole heck of a lot less soppy than the film) and Paid Servant.

And those books, and world events, led me on to Steve Biko and Nelson Mandela, to Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison, to Kwame Anthony Appiah, David Dabydeen and more recently to Reni Eddo Lodge and David Olusoga.

Meantime, the sound of Ghana, the highlife music that had wafted over from the student residences to our home on campus, was part of me. I was prepped to respond to black American music, to Motown and Stax and Philly, and to ska and reggae. And then I heard Osibisa, and that started a journey of exploration of African music – music from all over that continent, but finding the sounds of Mali and Senegal took hold of me in a way that no other music did. I still feel that way.

For all this, I realised part way through this year, as I nerdily compiled my list of what I’d read, that it was disappointingly, dispiritingly, shamefully white. Somehow I’d kept on gravitating (during what, to be fair, has been a brutal year, full of loss and sadness) towards familiar voices, familiar histories, familiar settings. That this realisation coincided with the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd is no coincidence at all.

However well I have been taught, however widely I have read and listened, my life can still be told (if one skips those few years in ‘darkest Africa’, as my grandfather always referred to it) without reference to my race. My journey through school and work, marriage and parenthood, has been untroubled by the colour of my skin. I have experienced prejudice, sure, as a woman in the workplace, and as a girl and woman in public spaces. I can extrapolate from those experiences, but it’s not enough, nowhere near.

So I need to read black writers, to hear those voices, those experiences and to let them expand my ideas, my sympathies, my knowledge. It’s powerful, and sometimes uncomfortable. But it’s a process that started when I was 5 or 6 years old, looking out of the Door of No Return.

Black lives matter. Of course they do. As the wonderful Dolly Parton put it, “…of course Black lives matter. Do we think our little white asses are the only ones that matter? No.” My words will make no real difference, I have few illusions on that front. But perhaps I will prompt someone to read more widely, to read more stuff by people who don’t look like they do, to risk being made uncomfortable, being challenged to rethink their assumptions, their bias, the language they use. Perhaps.

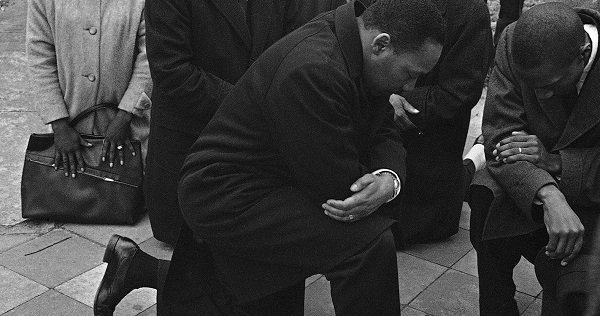

And would I take the knee? It’s a beautiful gesture, one of honour and respect. I wasn’t sure at first why it moved me so much, till I saw the photos of MLK and remembered. Yes, I’d take the knee, in a heartbeat. It might take a bit longer for me to get up again though…

My 2020 Reading List (so far):

- Chimamanda Adichie – Dear Ijeowole

- Arvind Adiga – The White Tiger

- Jeffrey Boakye – Black: Listed

- NoViolet Bulawayo – We Need New Names

- Angela Davis – Women, Race and Class

- Nicole Dennis Benn – Patsy

- Jason Diakite – A Drop of Midnight

- Bernardine Evaristo – Girl, Woman, Other

- Yaa Gyasi – Homegoing

- Mohsin Hamid – Exit West

- Afua Hirsch – Brit(ish)

- Meena Kandasamy – When I Hit You

- Andrea Levy – The Long Song

- Attica Locke – Pleasantville

- Kenan Malik – From Fatwa to Jihad

- Yvonne Adhimabo Owuor – Dust

- Laksmi Pamuntjiak – The Birdwoman’s Palate

- Johnny Pitts – Afropean

- Sunjeev Sahota – The Year of the Runaways

- Kamila Shamsie – Home Fire

- Margot Lee Shetterley – Hidden Figures

- Nikesh Shukla (ed.) – The Good Immigrant

- Ron Stallworth – Black Klansman

- Colson Whitehead – The Nickel Boys

#1 by Terry on August 30, 2020 - 4:26 am

You did this piece with great honesty and modesty. And I love your reading list! As long as we are learning, then we are heading in the right direction.

LikeLike

#2 by cathannabel on August 30, 2020 - 9:06 am

Thank you!

LikeLike

#3 by The TeeKay Take on August 30, 2020 - 2:20 pm

Well written! Chadwick’s death is truly devastating!

LikeLiked by 1 person